The Huskies’ resurgence to the top of the Pac-12 this year doesn’t just bring back memories of 1991. It recalls the first time Washington was the West Coast’s big dawg. That was a little more than 100 years ago, when what we now know as the Pac-12 rose out of the forests and mud in the wilderness of the Northwest, and was headquartered on the campus of the University of Washington’s Denny Field.

Known as the Pacific Northwest Intercollegiate Conference or “Big 6,” the league had six members: Washington, Washington State College, Oregon, Oregon Agriculture College, Idaho and Whitman. And Washington was such a power—it didn’t lose a game for 10 years—that the other five schools were sick and tired of playing second fiddle to the team from Montlake.

That Washington team was coached by Gilmour Dobie. Forgotten by many, Dobie experienced success here that exceeds that of even beloved Don James. Washington went undefeated from the last game of the 1907 season to the first game of 1917, a streak of 64 games (60 victories, no losses, four ties) and a winning percentage of .976 that still stands as an NCAA record for the longest unbeaten streak. Dobie’s teams accounted for 62 of these games with his remarkable unbeaten streak of 59 wins, no losses and three ties, outscoring opponents 1,930 to 118 and recording 42 shutouts.

Since that time, the conference has changed names, invited new members, dismissed others, and grown to its present-day version with 12 schools in the West. Today’s Pac-12 is a national juggernaut in both men’s and women’s sports, and has earned its nickname as the “conference of champions” many times over.

But let’s go back to the beginning.

In 1908, at the age of 30, Dobie took the reins as Washington’s head football coach. Dobie was born to be a coach, with skills he learned as a young boy at the school of hard knocks. When he was 8, he lost his parents. By 1886, in the dead of a harsh Minnesota winter, he was sent off to a “Public School” orphanage by his destitute stepmother. There, he lived under the stern control of matrons who ruled with ironfisted discipline. After only five months, he was indentured out to the first of four farm families, and he met even more severe hardship. Poorly clothed, overworked and with a farm family that didn’t keep their commitment to provide him with a proper education, he was sent back to the orphanage by order of the Public School State Agent.

Gilmour Dobie in Seattle, ca. 1915. Photo: MOHAI.

He suffered equally poor treatment when he was indentured out to two other families over the next two years; he even resorted to running away. His circumstances were so dire they even drew the attention of the governor of Minnesota, who intervened on Dobie’s behalf. It wasn’t until his fourth family that Dobie was finally well cared for and was able to receive a proper education.

He proved to be a very smart student who soon was at the head of his class. He ultimately went on to receive a law degree at the University of Minnesota, where he played quarterback. He was not only successful and hardworking, but humble; during his lifetime he never publicly revealed his orphanage background.

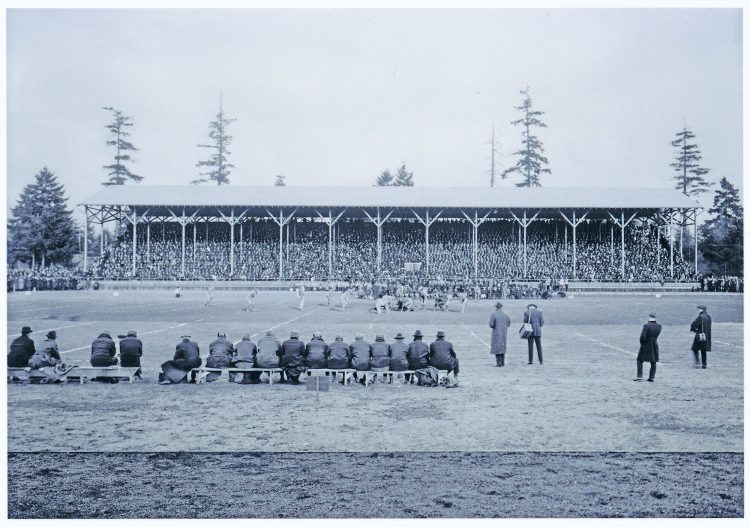

Football at Washington was first played on Denny Field beginning on an up-note with a 12-0 victory over the Seattle Athletic Club on Oct. 19, 1895. The original bleachers were made of simple wood-frame construction, placed level with the playing field, and had a capacity of 4,000. The soil was permeated with rocks that worked their way to the surface despite the fact that young boys were often hired to scour the field for rock-removal duty. It was rare for football fields of this era to have grass, and Denny Field was no exception. Coupled with poor drainage and football-season rainstorms, many games were played in a cold, wet, muddy quagmire.

But Dobie’s success boosted attendance and called for construction of more comfortable, elevated bleachers in 1910 that could seat 9,000 fans. The Denny Field grounds and vacant land surrounding the field no longer host sports; that space will become home to more on-campus housing as well as new academic and administrative facilities. A commemorative plaque will be installed to honor the rich history of Denny Field as the campus athletic grounds of a century ago.

By 1914, Washington was the acknowledged football power of the West with its undefeated streak dating to the last game of 1907. Of course, the deck was stacked in Washington’s favor, since it was the largest university in the most populous city in the Northwest. Washington drew the biggest crowds, with the consequent biggest payouts to both teams. With its commanding edge at the bargaining table, Washington was able to gain home-field advantage for 71 percent of its league games. This, coupled with Dobie’s strong personality and recalcitrant manner, led to even more fireworks and ultimately the demise of the Big 6.

UW players sit on the bench donning overcoats during Gilmour Dobie’s final game, a 14-7 victory over California on Nov. 30, 1916 at Denny Field. Dobie is standing on what looks to be the 50-yard line, just left of the man with the square box hanging from his shoulder. Photo: MOHAI.

That fall, UW alum Victor Zednick, a former graduate manager of student affairs whose duties essentially included those of today’s athletic director, served as president of the Big 6. He wrote to all schools in the league, plus California and Stanford. He recommended that a new league be formed comprised of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Washington State College, Oregon Agricultural College, California and Stanford. It would be called the Pacific Coast Athletic Association. Because of the many serious injuries and deaths in football back in the early 1900s, California and Stanford had given up football for rugby. It was anticipated that with new rules to reduce injuries, along with intervention from President Theodore Roosevelt, the California schools would return to football.

But with Dobie’s Washington squad again posting a 7-0 season, the other five teams joined in a plot to unseat the king. His competitors all met before the 1914 conference in Spokane with one purpose in mind: bring down the dynasty!

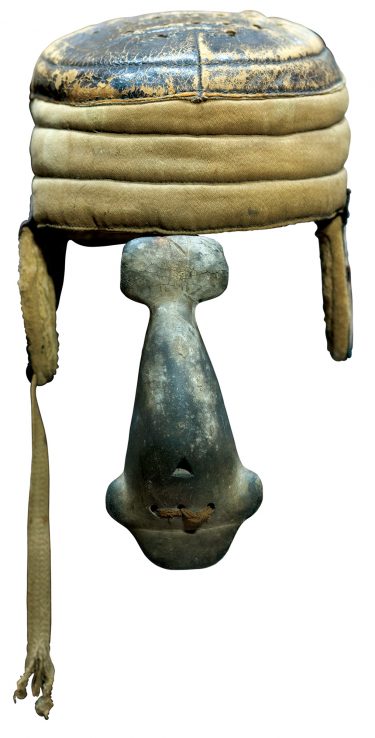

The first 20 years of football were distinguished by rough games and limited protective gear, but by 1910, the UW football team wore helmets like this one. Some players protected their noses and mouths with guards suspended from the front. Courtesy: Dr. Ray Cardwell.

The cabal presented its demands at the formal league gathering to Washington’s graduate manager, Art Younger, with a schedule completely at odds with Dobie’s wishes. But despite the ultimatums offered in a take-it-or-leave-it attitude, both sides wouldn’t budge. It was now clear to both Younger and Dobie that they were caught with the door slammed shut on further negotiation—and the cabal’s stubbornness won out.

Washington was left to schedule only one league game with tiny Whitman. This left the Big 6 Conference in shambles and opened the door for its marquee team to reach out to California and Colorado to complete its schedule for the 1915 season. But the off-field turmoil didn’t affect Washington’s play one bit. The Big Dawg from Seattle outscored its seven opponents in 1915 by a commanding 274–14.

On Dec. 2, 1915, the annual league conference was held in Portland. A dark cloud hung over the event, due to the prior year’s insurrection to undercut Dobie’s dominance. With the Pacific Northwest Intercollegiate Conference tottering on the brink of disaster, another Dobie-led obstacle was added to the mix: his requirement that Washington would only schedule games with schools that agreed to exclude freshmen from the varsity roster. Washington State College, Whitman and Idaho pulled out, afraid that the eligibility rule would place them at a competitive disadvantage.

Washington thus joined California, Oregon and Oregon Agricultural College as charter members of the Pacific Coast Conference (PCC). Stanford delegates attended the meeting, but because they favored rugby, they stubbornly refused to play American Rules Football. Washington and California are the only two members who have held continuous membership since the conference began. Technically, the league was founded on Dec. 3, 1915, as it wasn’t until 1:30 a.m., after long hours of horse-trading, that all of the details were hammered out.

Washington State College was admitted as a member in 1916, competing in all sports along with Stanford, which didn’t compete in the PCC in football until 1919. USC and Idaho were admitted in 1922, Montana in 1924 and UCLA in 1928. History clearly reflects that the opposing league members’ attempted coup to unseat Dobie and his subsequent position to exclude freshmen from varsity football led to the creation of what we know today as the Pac-12. Zednick, the former UW graduate manager, said it best: “Despite all the heartaches Dobie gave me, he was one of the finest men I ever had the pleasure of knowing. He was a builder of men and one of the few real coaches the game of football has had.”

Washington and Oregon both went undefeated for the inaugural 1916 PCC season. But since league officials ruled that Oregon had used an ineligible man in two games, the first Pacific Coast Conference championship was awarded to Washington.

Fast forward 100 years, and look at the top of the standings. You’ll see a familiar name there.