Never Kenough Never Kenough Never Kenough

After decades at ESPN, Kenny Mayne tells us how he spends his time.

By Mike Seely | March 2025

One of Taelor Scott’s earliest memories occurred when she was about 3 years old. Now in her twenties, the daughter of the late, great ESPN broadcaster Stuart Scott was driving to a Connecticut transfer station with a man she affectionately called “Uncle Kenny.”

When they got to the dump, Uncle Kenny disposed of the refuse in the back of his truck and told young Taelor, “You put it in there and it burns at the bottom.”

Uncle Kenny—full name: Kenny Mayne III—was no casual observer of trash. When he attended college at the University of Nevada-Las Vegas, the Kent, Washington, native worked as a garbage man every summer upon returning home. And when he found himself between broadcast journalism jobs in the late 1980s, the first person he called while looking for work was his old boss with the trash-collecting company.

One problem: By that point in time, there was just one worker assigned to each truck, with automation negating the need for “swampers.”

“It was like the industry had passed me by in those intervening times,” said Mayne, who’d just finished a seven-year stint with Seattle’s KSTW-TV, where he’d started as a production assistant fresh out of UNLV in 1982 and eventually ascended to the role of weekend sports anchor.

Mayne’s inquiry to his former employer wasn’t all for naught, however. His old boss offered him a job assembling garbage cans.

“I’m like, ‘What the fuck did I just do?’” Mayne remembers thinking. “I just quit a TV job that wasn’t paying a lot, but relatively speaking, it was. Now I’m working for $10 an hour making garbage cans in the rain.

“I’m not saying this like I’m above garbage. I was a garbage man. I have great respect for them, right? I just mean it wasn’t what I was hoping to do after seven years out of college.”

Mere months earlier, Mayne had interviewed for a job with ESPN. He was passed over that first go-round, but the experience gave him the confidence to leave the comforts of his local news gig and shoot for the moon.

Five years and an assortment of odd jobs and freelance assignments later, he finally landed on the lunar surface, joining the Worldwide Leader’s off-kilter ESPN2 staff in 1994. By the time he left ESPN in 2021, he was regarded as one of the most unique and formidable talents to have ever graced the SportsCenter desk, the funniest guy in a room filled with quick-witted people who’d summited their profession.

Mayne has stayed busy since leaving ESPN, with numerous projects set to pop—including a vehicle that, if it secures distribution, would feature the University of Washington prominently. If those five years of limbo between ’89 and ’94 taught him anything, it’s that good things come to those who hustle.

But there’s another side to Mayne, one touched by familial tragedy and a debilitating injury. To a person, friends and former co-workers describe him as extraordinarily charitable and empathetic. The lovable wise ass you’ve seen on TV? Yeah, he’s that guy—and so much more.

Garbage cans & broken ankles

Kenny Mayne did not aspire to be a sportscaster as a youngster growing up in South King County.

Every evening, at 6 o’clock, his family would pause to discuss politics and current events. If he was to have a career in broadcasting, he saw himself following in the footsteps of serious newsmen like Walter Cronkite or David Brinkley, not Dan Patrick or Chris Berman.

“I always covered serious things seriously and the rest of it less seriously and I found that most of the rest of it, you know, they’re just games,” says Mayne. “I know it matters—the fans are passionate and the players’ skill level I appreciate and had an admiration for. But as far as calling a highlight, I thought it was supposed to be kind of fun.”

Mayne was a good schoolboy athlete, starring at quarterback for Jefferson High School in Federal Way. In assessing his collegiate future in the sport, he first tried to walk on at the UW at a time when Warren Moon was the incumbent QB and Tom Flick was waiting in the wings.

“I went to the UW for five days, but that’s still where I’m from. They’re the home team and I’m always rooting for their success.”

Kenny Mayne

Mayne felt he was better than another freshman signal-caller, but since that freshman was on scholarship, Mayne came to the conclusion that he “wasn’t gonna get the look that I hoped to get” and decamped for Wenatchee Valley College, a two-year school that was desirous of his services.

He thrived in Wenatchee and attracted the interest of University of Nevada, Las Vegas. Mayne’s father, who attended the UW briefly as an undergrad, worked as a passenger agent at Sea-Tac Airport and had taken his son to Sin City a couple of times after securing steeply discounted airfare. It was a place young Kenny was comfortable with, and he quickly took a liking to his teammates and the style of offense the Runnin’ Rebels employed.

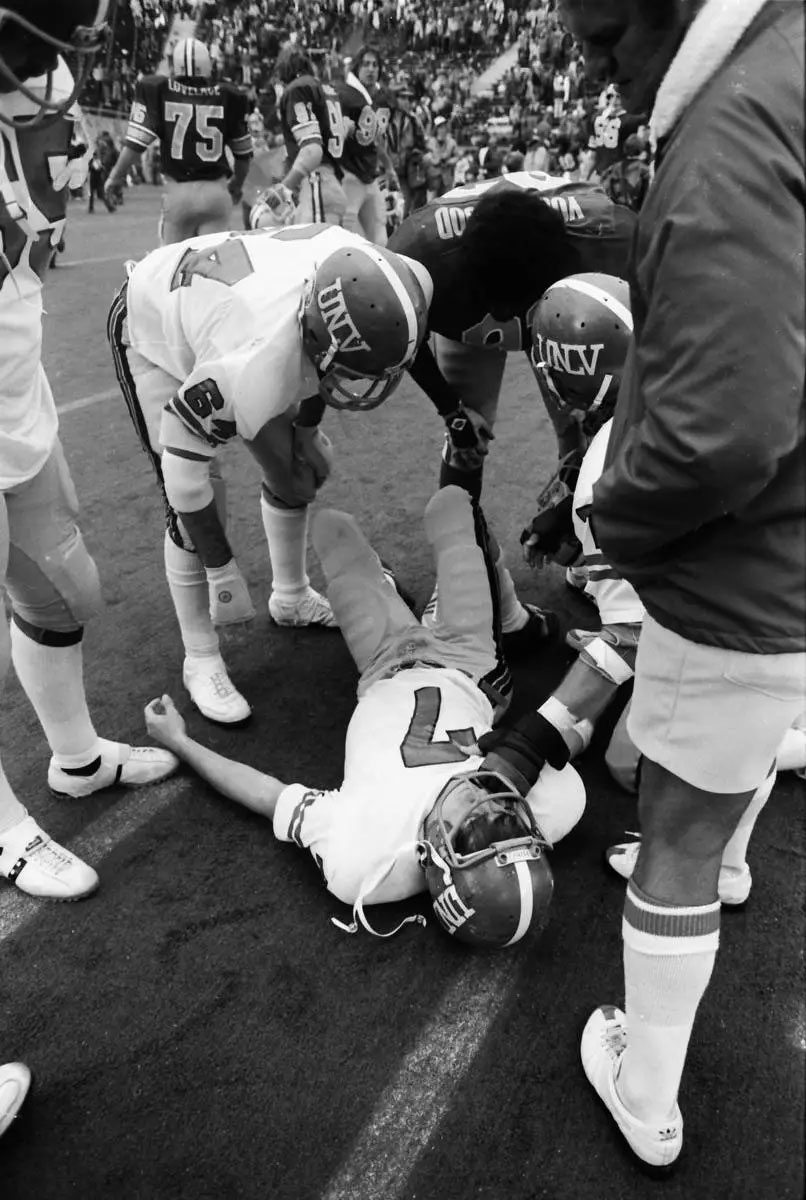

After redshirting in 1979, Mayne was backing up starting quarterback Larry Gentry in 1980 when he was inserted late in what would wind up being a blowout loss to the University of Oregon. On the last play of the game, Mayne went back to pass. As he released the ball, a defender barreled into his right ankle, helmet first, shredding its ligaments and snapping a fibula.

- UNLV teammates check on Kenny Mayne after he sustained an injury in Oregon on Oct. 25, 1980. Photo courtesy of The Register Guard.

- While playing against Oregon for UNLV, Kenny Mayne broke his right ankle on Oct. 25, 1980. Photo courtesy of The Register Guard.

His ankle now filled with plates and screws, Mayne returned as a senior to again back up Sam King and graduated with a broadcasting degree in 1982. The Seattle Seahawks, of all teams, gave him a tryout, and Mayne was impressive enough to earn a multi-year contract.

But for everything to be finalized, Mayne would have to pass a physical examination, which scuttled the deal and scared off other suitors.

“I wasn’t a big enough star for somebody to overlook the fact that I had this ruined ankle,” he says.

As Mayne shifted focus to his career at KSTW, his ankle didn’t give him many issues in his twenties. But once he got into his thirties, he began limping a lot and had some bone spurs removed. A dozen surgeries later, Mayne was about 50 when his old injury became, in his words, “a serious disability.”

“I’m getting out of bed, a little depressed, like, ‘Oh, shit, I gotta step on this thing and go to the bathroom or I gotta fly somewhere the next day and it’s gonna blow up on the plane.”

Mayne considered his options. In the space of a single week, he says he “went to see an amputation guy, a fusion guy and a replacement guy—and it was the amputation guy who kind of changed and saved my life.”

That guy encouraged Mayne to get an ankle brace and better therapy rather than lopping it off. Mayne, who spends most of his time nowadays in Connecticut but has a home in Kirkland, was living in the Seattle area at the time and took his daughters swimming. He bumped into one of their middle school physical education teachers, who noticed Mayne limping and offered to connect him with a highly regarded chiropractor by the name of Neno Pribic.

The thing about chiropractors is they’re often able to work wonders on part of the body that aren’t a person’s back, and Pribic was one such practitioner.

“He worked on it and manipulated it and cracked it and pulled it and did whatever,” recalls Mayne. “I just had to trust that it wasn’t gonna hurt any more than it already did. And he really did bring it back to life.”

Feeling encouraged by his physical condition for the first time in decades, Mayne got connected with a “mad scientist” in Southern California named Marmaduke Loke. He specialized in braces, outfitting Mayne with one that allowed him to play flag football a month later without experiencing any pain.

While that brace was effective, Mayne eventually found one in Gig Harbor that was easier to put on and allowed him to do more things with less pain. This is the brace that Mayne’s nonprofit foundation, Run Freely, gives to military veterans with mobility issues.

To raise funds to purchase the braces, Mayne has enlisted a slew of star athletes—including former UW quarterback Michael Penix, who threw passes to fans who generously donated to Run Freely in order to catch his gorgeous spirals at Husky Stadium. Adidas also hired Mayne to do voice-over work for a hype video promoting Penix’s Heisman Trophy candidacy.

“He was great to me, helping out my foundation,” says Mayne of the Atlanta Falcons rookie.

As for his feelings about the UW, Mayne says, “I went there for five days, but that’s still where I’m from. They’re the home team and I’m always rooting for their success.”

‘You can’t go to-to-toe with him’

Having recently moved on from his garbage can-assembly gig, Mayne was selling prepaid legal insurance in the early ’90s when he got a call from a former co-worker at KSTW, Jesse Jones, who has since moved on to KIRO-TV.

Jones told Mayne that ESPN’s top talent scout, Al Jaffe, was interested in revisiting whether there might be a role for Mayne at ESPN. The network put him to work doing some freelance segments and eventually hired him full-time.

“Jaffe comes to us with this guy who’s making garbage cans and we look at tape on him,” says former ESPN executive Vince Doria. “He’s a unique character. His cadence is different from what most people who make successful broadcast careers do. But there was something about him. He clearly had this dry sense of humor that attracted me.

“Right off the bat, he fit in. He’s not full of himself, [he] laughs at himself. We started doing some offbeat pieces with him. He clearly had a knack for doing things from a different perspective.”

“He’d talk about the craft-beer crowd and Gen Z, almost making fun of the vehicle that we were on,” said ESPN anchor John Bucigross. “I’ll always remember that playful side of him, but he definitely took the performance seriously. He wanted to perform mostly in a comedic way.”

While he’s best-known for his SportsCenter exploits, Mayne did it all at ESPN over the course of his 27-year career, covering horse and auto racing, handling pitchman duties at the network’s advertiser upfronts and starring in a web series called Mayne Street that featured an up-and-coming actress named Aubrey Plaza. He also hosted a weekly segment called The Mayne Event, where he once got Buffalo Bills running back Marshawn Lynch to star in a charming bit about the future Seahawk legend’s love of Applebee’s and other chain restaurants.

“Kenny would come to someone with this idea that made total sense to Kenny but was really half-baked to someone who didn’t have his sense of humor,” says SportsCenter anchor Scott Van Pelt. “Every once in a while, he’d meet someone who had the vision. Marshawn Lynch had the vision. That’s the kind of shit Kenny would be sitting there with—‘I’m gonna go to Applebee’s with Marshawn Lynch and it’s going to be hysterical.’ Kenny has an amazing way of giving people who don’t have the vision the vision.”

“His humor was so esoteric, you had to really pay attention to get it,” adds ESPN anchor Stan Verrett. “But when you got it, it was hilarious. His approach was just so unique. It was totally organic. It was him. There have been people who’ve come along who tried to copy it, but they’re not Kenny Mayne.”

Another admiring ESPN colleague of Mayne’s, Neil Everett, was working for a news station in Hawaii when a cameraman there told him about “this guy in Seattle” who’s “gonna be on SportsCenter someday.” That guy was Mayne.

“The first time I got to do a show with Kenny, it was a big deal to me,” says Everett. “You can’t go toe-to-toe with him or you’re gonna get knocked out. He got me several times in L.A. where I couldn’t speak—on the air.”

“He’s the only guy I ever worked with where I had to go read his stuff beforehand to prepare myself,” says fellow anchor John Anderson. “I’m going to have to bite my lip because that’s funny to me.”

Delving a bit deeper into the psyche of his longtime friend, Anderson adds, “I don’t know that there are as many people with the depth of empathy he has for people, how he cares for other people, what he will do for other people. I don’t think people see that all the time because they get distracted by the funny.”

“The year before I left to go to the UK, our families had dinner in West Hartford,” says Stuart Scott’s other daughter, Sydni, who is currently a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford working on her thesis about reparations in a global context. “[Kenny] has been a mainstay in our life in terms of support. After I won the Rhodes Scholarship, he tweeted about it. Somebody came for him—“reparations, it’s never gonna happen”—and he was firing back. He’s just this fiery contender and we have always felt the fierceness of that love and support.”

“I think that’s why he and my dad got along so well,” adds Taelor. “They understood that.”

‘How could anything be funny again when you’re that sad?

In 1996, Mayne’s then-wife, Laura, was pregnant with twin boys. They were on vacation in Maine when she began experiencing extreme discomfort and it became apparent that the twins would have to be delivered prematurely.

One boy, Creighton, was stillborn upon delivery. The other, Connor, fought like hell to stay alive but died six months later.

Now the father of four adult daughters in a blended family with his current wife, Gretchen, Mayne says he still feels the twin boys’ presence “in little ways.”

“That’s a hugely significant thing in your life,” he says of their passing. “I like it when people bring them up because then they’re remembered. I don’t like that they aren’t acknowledged. They were real people. Connor, I knew far better. He lived for six months. Creighton didn’t [live] at all. Connor was fighting to get his way out.

“ESPN was very good to me. They gave me as much time as I needed off. It felt good to go back to work because it made things feel more positive. The thought crosses your mind: How could anything be funny again when you’re that sad? But I don’t think they would want me to go through the rest of my life giving up.”

Stephen Panus had thoughts of giving up when his 16-year-old son, Jake, was killed in a drunk-driving accident in 2020.

“In the wake of losing Jake, Kenny Mayne was one of the first people to reach out to me and provide hope amidst a backdrop of complete darkness,” Panus says. “Kenny and I knew each other and were friends from horse racing. As a bereaved father himself, Kenny intimately knew the arduous road I now found myself upon and his support meant the world.

“Nearly four years later, when I announced that I was [going to] launch my own strategic marketing, branding and public relations agency, Kenny texted me immediately and wanted to talk about me representing him. We spoke a few hours later, and Kenny quickly became a client.”

Among the many projects Panus and Mayne have in the hopper is a quasi-reality show, Mayne, Image & Likeness (and obvious play on the NIL situation that’s changed the face of college sports), which found Mayne shadowing the UW football team throughout the 2023-2024 season.

Another is a 30-minute documentary short that screened at the most recent Seattle International Film Festival. It’s centered on Mayne, then a young man working at KSTW, attempting to throw a wiffle ball faster than Ken Griffey Jr. at a Pacific Science Center exhibit, and features a hilarious deadpan cameo from Ken Burns.

The radar gun determined that they threw the plastic ball with equal velocity, but Mayne couldn’t get over the fact that he thought he threw the ball faster, going so far as to enlist Duane Storti, a professor of mechanical engineering at the UW, to confirm his suspicion.

It would be inappropriate to give away Storti’s—and the film’s—conclusion in this space. As with anything involving Mayne, you’ll have to watch to find out.

“Kenny Mayne’s Wiffle Ball” is now streaming on Fubo, Amazon Freevee, LG Channels, Samsung TV Plus, Sling Freestream, The Roku Channel, VIZIO WatchFree+, Tubi, Plex and Tablo TV or as part of Fubo’s subscription packages.

Lead photo courtesy of Kenny Mayne/ESPN Wider World of Sports.