In the Children’s Garden in Seattle’s Wallingford neighborhood, between the kiwis and cardoons, Nathanael Mengist has found his calling. His office comprises more than a dozen garden beds and a weedy world of herbs and vegetables. The tools of his trade include little rakes, colored pens and a ukulele.

Mengist, ’15, ’16, is head of the children’s garden program at Tilth Alliance, a nonprofit that aims to build an ecologically sound, socially equitable food system. For the last two years, he has taught children about the natural world, how to grow food, and how to care for themselves and others. On one recent day, his work involved talking with children from around the city about cage-free eggs.

“Yuck,” said one of his students, hearing about the eggs. Mengist wondered, “Why yuck?” He opened up the conversation, explaining that some hens are packed in small cages and some are allowed roam free. “Which do you think make better eggs?” he asked. The children’s faces dawned with understanding.

“I want all children to have access to and understanding about our food and what is healthy and what isn’t,” says Mengist. “That’s why I think this job is so important.”

When Mengist first enrolled at the UW, he envisioned a career in medical science. But during his first year he realized he wouldn’t find happiness in a laboratory. Searching for a new field of study, he discovered the Comparative History of Ideas program. It was exactly the type of learning and examination of the world that appealed him. That curiosity led him to explore science and history and, more deeply, the relationships humans have with food and health. That also brought him to his current work at Tilth Alliance.

Mengist’s story—that of a liberal arts background leading to an unexpected and satisfying career—is a familiar one to Robert Stacey, dean of the College of Arts & Sciences. It’s a story that bears repeating, particularly as the University is seeing a significant decline in the number of students studying liberal-arts disciplines like history, classics, foreign languages and literature.

To offer one example, the UW’s history department has seen a drop of more than 50 percent in undergraduate majors in the last decade. The collapse in English majors has been nearly as precipitous, says Stacey. Some humanities departments have experienced even steeper declines—down by more than 60 percent—in the past five years. And it’s not just that fewer students are choosing humanities majors; fewer are taking humanities classes across the board. Nationally, the number of bachelor’s degrees in the humanities follows a similar trend.

Nathanael Mengist, Comparative History of Ideas, ’15, ’16

By contrast, “the degrees that can be seen as vocational—leading toward a fairly specific sort of job—their enrollments are expanding,” says Stacey. “This is a national phenomenon. But it’s more dramatic in this region, I think, because we are in such a tech bubble.”

Sometimes students are hesitant to choose a liberal-arts major because the career path may not be as obvious, says Stacey. Other times, families, fearing a student’s earning potential right out of school will be lower, pressure them to pursue a degree that they believe will lead to a higher-paying job. There’s also the perception—unfounded, says Stacey—that our country needs more science, technology, engineering and math graduates but not English or art history majors. He points to a recent Economic Policy Institute study that found that in fact only 50 percent of information technology graduates, including computer science majors, find jobs that require a STEM degree.

This debate between STEM and liberal arts actually takes things in the wrong direction, says Stacey. What’s more important is that workers can stick with difficult challenges, think analytically, be curious and communicate effectively with a variety of audiences—skills at the heart of a liberal arts education.

Looking ahead, workers will also need the flexibility of mind to adapt to new careers. “If current predictions hold true, students graduating today will hold 15 different jobs before they retire from the workforce,” Stacey explains. “Many of those jobs don’t even exist yet. So what will determine the long-term success of our students is not their first job, but their capacity to adapt to a rapidly and constantly changing economic and social landscape. That’s where the breadth and depth of a liberal-arts education can be a huge benefit.”

To demonstrate that liberal-arts degrees lead to an almost infinite range of satisfying careers, the College of Arts & Sciences has created an interactive online quiz featuring alumni from arts and sciences disciplines who have landed jobs in fields ranging from arts management to finance to human rights advocacy to health care.

The quiz highlights people like Jacob McMurray, ’95, an anthropology and Danish language and literature major who now works as the senior curator at Seattle’s Museum of Pop Culture, and visual communication design major Luly Yang, ’90, known internationally for her wedding dresses and couture gowns. Today Yang is working on such high-profile projects as the design of Alaska Airline’s new uniforms.

What's important is that workers can stick with difficult challenges, think analytically, be curious and communicate effectively with a variety of audiences—skills at the heart of a liberal arts education.

English major Matthew Moore, a video game designer, says he was as much helped by his choice of major as he was fulfilled by it. “I took a lot of classes I really loved,” says Moore, ’08, recalling courses on Shakespeare, crime fiction, and comedy in classical English lit. “I thought, I’m home here. This is where I belong.”

Moore was a little worried that his English degree might hamper his prospects when he applied for a job as a game tester at Microsoft. Instead, the hiring manager saw his degree as an asset. Moore could use his skills to train new game testers and write reports about problems they discovered in the games. That job led to one at ArenaNet as a copy editor, again drawing on the positive associations people had with his English degree. From there, Moore moved into game design and then to a job with Disney Interactive.

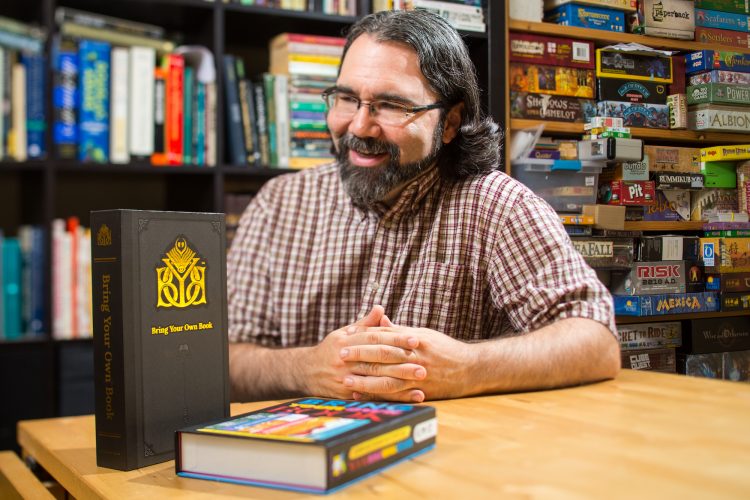

English major Matthew Moore, ’08

Today Moore works on contract for Microsoft, testing user experience for a virtual reality project. He also has his own business producing table-top and digital games. His first game, “Bring Your Own Book” (he was an English major, after all), is about to be released as an app.

While Moore was taking English classes, Amanda Morse, ’09, ’14, was pursuing a classics major. She thought she might become a Latin teacher or museum archivist. “Neither was a great fit,” she says. Instead, she was drawn to public health. Today, Morse is at the state Department of Health, working with the Rapid Health Information Network as a policy coordinator, helping other offices and agencies use data from outbreaks like measles or food-borne illness to make decisions about how to respond.

Morse, who went on to earn her master’s in public health in 2016, says her undergraduate studies were critical to her success. She credits the influence of Cicero, a Roman politician and writer, and her history studies, for helping her learn how to write persuasively. “Knowing how to craft an argument, knowing how to bring someone to your side, these are really important skills that I don’t think I would have learned had I been a biology major,” she says.

Classics major Amanda Morse, ’09, ’14

Students like Morse may take some time to find their path; others start out closer to a career than they realize. Christina Salguero arrived at the UW in 2006 as a community college transfer student from Spokane, fixed on studying psychology. “I just knew that understanding the human mind was fascinating to me,” she says. But she didn’t know where it would lead.

A few years after college, Salguero joined the Peace Corps in Guatemala. There she helped young people develop life skills and assisted teachers and parents in learning how to offer the same type of support. “It helped me see the value of being a stable person who can give kids hard skills in how to walk through life,” she says.

Now Salguero, ’08, is the clinical manager with Friends of Youth, an organization for at-risk boys and girls. There, she focuses on helping adolescent boys learn to make healthy choices and be self-sufficient. It’s work, she says, that completely suits her values and interests.

For Salguero, a UW liberal-arts degree was about pursuing what fascinated her and then finding a career that rewarded her. “I like working with adolescents who are figuring out their own path,” she says. “I help them risk-manage while they’re finding themselves.”

Psychology major Christina Salguero, ’08

Her advice to current students? “You don’t need to completely define your life, but have a set of values that guides you in your career and your personal life.” As for working in social services, “Our job is never going to be taken over by robots,” she says. “And the nation needs people who care about other people.”

Whatever you’re into, there’s a way to turn it into a job. Wanting to offer students a perspective on where they could go with a liberal-arts degree, the College of Arts & Sciences has created an online quiz to debunk the notion that certain degrees may not be the path to a great job.

By answering three questions, users can find stories of alumni whose careers reflect interests similar to theirs. They will find profiles and advice from the likes of James Beard Award-winning food blogger Molly Wizenberg, actor Joel McHale, winemaker Angela Jacobs, radio host Luke Burbank, and Rick Welts, president and COO of the Golden State Warriors.

Already more than 250 alumni—playwrights and producers, museum curators, zookeepers, video game designers, and NASA scientists among them—have shared their stories, offering proof that liberal arts majors can find great jobs after college. Take the quiz!