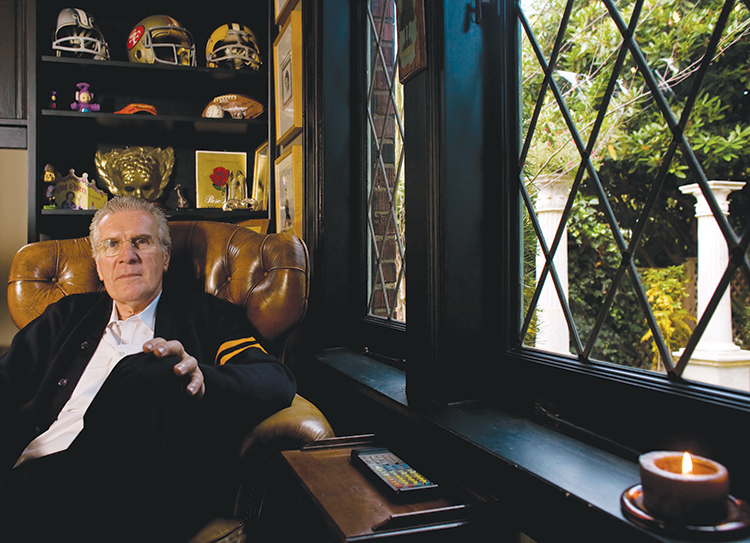

David Kopay is a study in contradictions. He has retained his jocular handsomeness and muscular build, reminders of the imposing athlete he once was. They belie his age, his arthritis, and the litany of surgeries he has undergone the past several years — a pair of hip replacements, his right knee, his right shoulder. And he remains a public figure — an icon, even — but of the most reluctant sort. He lives alone in an elegantly understated home on a quiet street atop Queen Anne Hill, his days filled with the silence of time. The wall of privacy he has constructed around himself in the autumn of his life affords the solitude he so clearly desires. He is most at peace by himself.

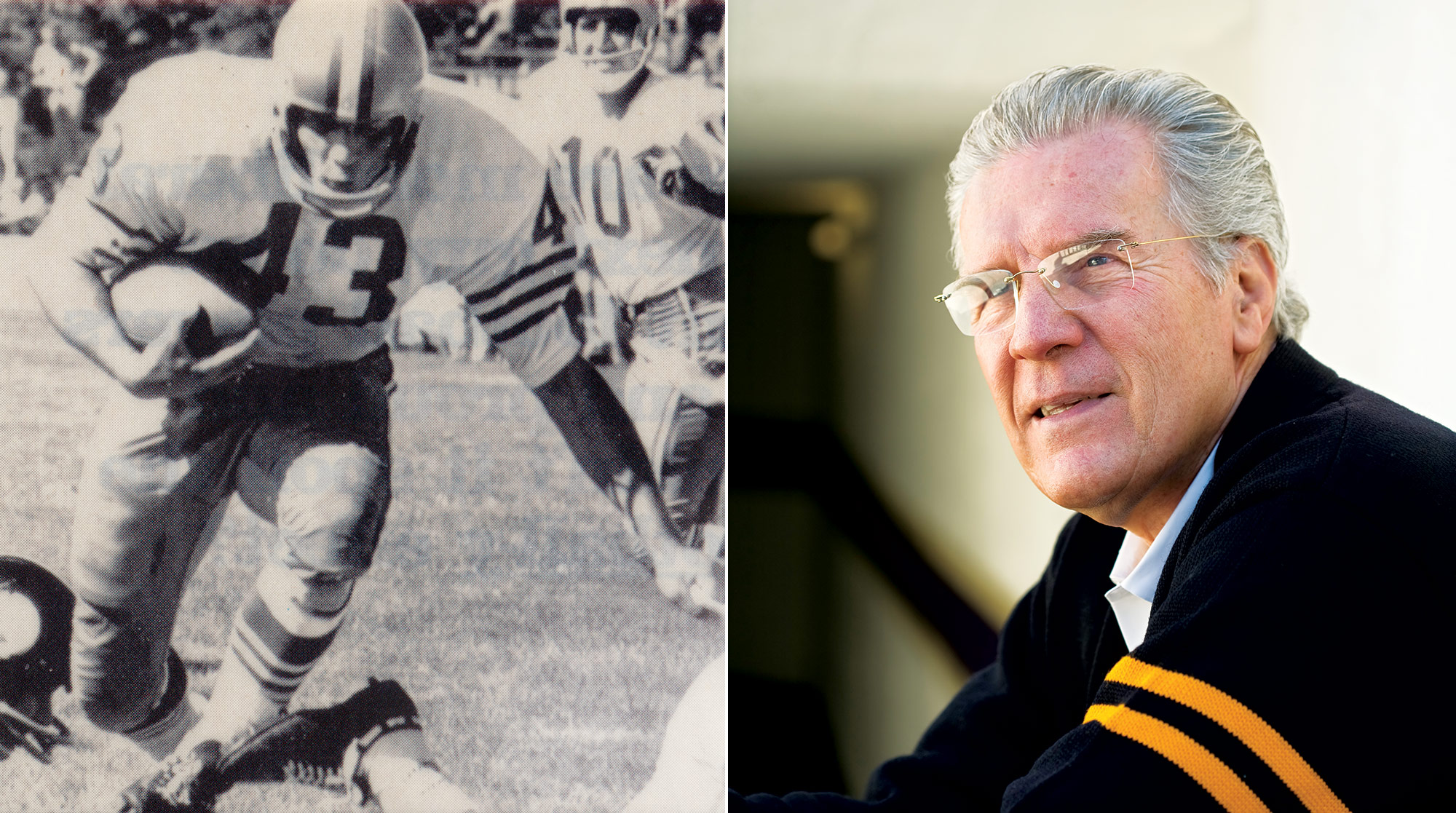

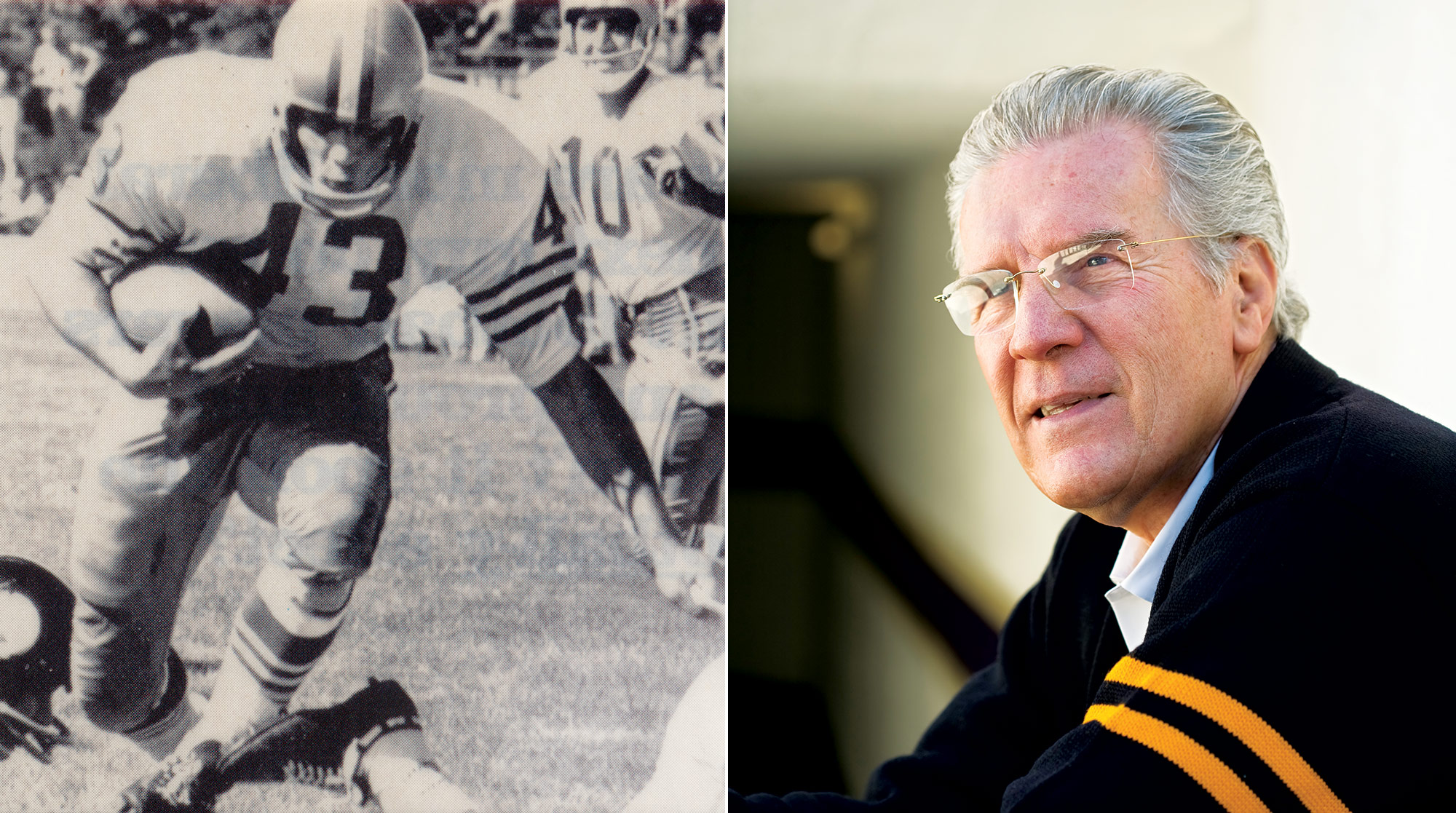

If Kopay, ’64, seems reconciled to these contradictions, it may be because they are nothing compared to the one he lived for so long. This is a man who, while an All-American running back at the University of Washington in the early 1960s, was known for his hard-nosed playing style, and who carved out nine seasons in the National Football League on grit and moxie. This is also a man who, in 1975, became the first professional athlete from a major team sport (he retired from the NFL in 1972) to announce publicly that he was gay — an act of candor that turned the most masculine of sports on its head, shattering its definitions of courage and toughness.

Now Kopay is doing what he can to ensure that UW students don’t have to live the contradiction he lived. Last September, he announced he would leave an endowment of $1 million to the University’s Q Center — a resource and support center for gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender students and faculty. He believes it’s one of the most important efforts he will ever undertake. Three months later, he left Southern California and the life he had spent three decades building and returned to Seattle, to be closer to a university from which he has at times felt quite distant.

“I wanted to do something meaningful, to leave something behind that would benefit people whose experiences and feelings I shared and can understand,” he says. “I wish there had been something like the Q Center when I was a student. This city, the University, everything is so different from when I was a student here. It’s been wonderful to see how the social climate has changed.”

***

Kopay, 66, grew up in Southern California in a staunchly Catholic family. He was the second of four children, an altar boy. Even as a child, he understood that the attraction he felt toward his male friends was somehow different. An immense sense of guilt, the product of his strict Catholic upbringing, drove him to enter a junior seminary in his early teens, in the hopes of becoming a priest and, in his words, “curing” himself. But there, his feelings only intensified, and he was deeply attracted to his fellow seminarians. He turned to prayer to pour out the guilt he felt. “But even with all my prayers and acts of contrition,” Kopay said in a 2005 speech, “I wasn’t getting any relief or success in dealing with my deep secret.”

Kopay transferred to Notre Dame High School in Sherman Oaks, where he grew into a talented football player. Heavily recruited, he decided to attend Marquette University, a Jesuit school in Milwaukee, Wis., after his childhood favorite, Notre Dame, failed to offer him a scholarship. When Marquette dropped its football program the next year, he transferred to the UW, where his older brother, Tony, was on the team.

Kopay transferred to Notre Dame High School in Sherman Oaks, where he grew into a talented football player. Heavily recruited, he decided to attend Marquette University, a Jesuit school in Milwaukee, Wis., after his childhood favorite, Notre Dame, failed to offer him a scholarship. When Marquette dropped its football program the next year, he transferred to the UW, where his older brother, Tony, was on the team.

Kopay joined the Theta Chi fraternity when he arrived at the UW, and it was at the fraternity that he met the man he now calls the great love of his life. But the very idea of being gay was still foreign to him at the time. This was the early 1960s, and to declare his homosexuality would have tarred him as an outlier. The thought frightened and repulsed him. He was a football player, after all.

That remained his mindset throughout his time at the UW, even as he and his fraternity brother slept together on the sleeping porch of their house, their encounters often taking place after both had dropped off dates. He had closeted himself so completely, insulated by his fear and insecurity, that he never attempted to seek out others in his position, much less the city’s gay enclaves. It would take more than a decade for him to begin confronting his sexuality.

As his personal life grew increasingly complicated and clandestine, Kopay also struggled on the football field, failing to earn a varsity letter in his junior year. He finally broke through in his senior season, averaging over 48 minutes a game to lead the team. He was named an All-American and led the Huskies to the 1964 Rose Bowl. It should have been a joyous time for Kopay, but he continued to feel burdened by the weight of the secret he was keeping.

***

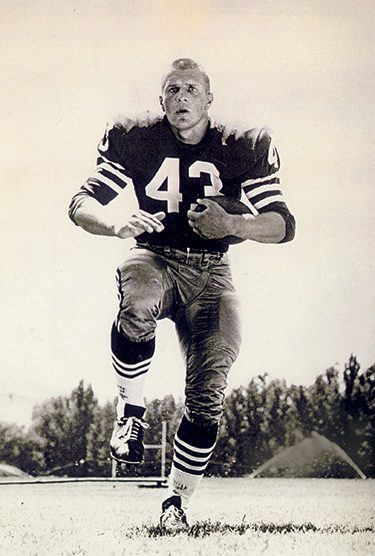

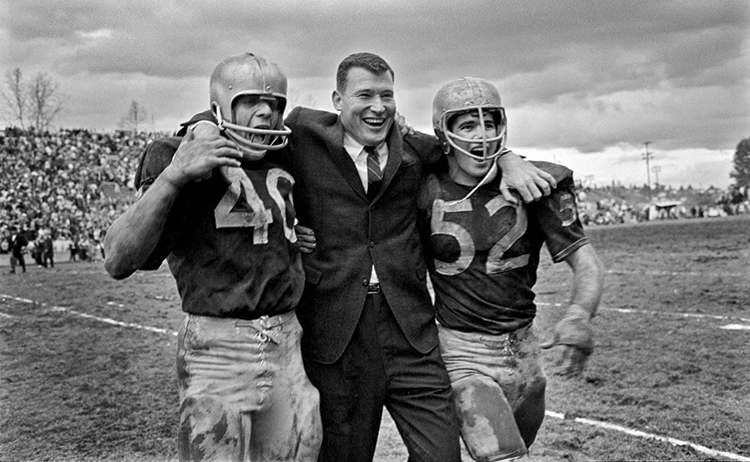

Kopay (left) horses around with Coach Jim Owens and a teammate at a 1962 game in Husky Stadium.

Years later, when he finally went public about his homosexuality, some former teammates were amazed at his ability to perform under so much internal strain. “It certainly had to be a challenge for him, seeing the world through his eyes at that time,” says Rick Redman, ‘66, a former UW teammate. “I am happy for him, the way in which he handled himself, and how he was able to perform under the conditions he was facing. I am proud to call him a teammate.” In the years that followed, Kopay continued to wear a mask of heterosexual maleness — getting married (and later divorced) and feigning interest in chasing women, hoping to suppress his internal struggle, continuing to live his lie.

“I was never thinking I was a gay man, because I just wasn’t like ‘one of them,’ “ Kopay says. “Just talking about it like that almost reinforces the utter bullshit that society uses to identify gay folks. I didn’t have the knowledge or strength to take it on then, and even after I did take it on, there were many, many times that it almost consumed me and took me into deep, deep depression. I grew to really appreciate the thousands of letters people sent me telling their own stories, but sometimes even that wasn’t enough.”

When Kopay came out three years after retiring from football, he had no intention of becoming an advocate for gay rights. Nine years in the NFL had formed a public image of Kopay as a lunch-pail-tough character. Blue-collar and overachieving, he blended perfectly into the NFL of that era, a sport built on collisions and brutality, where introspection and self-awareness were unwelcome visitors. Even today, the league remains a world where toughness is prized, and where weakness, defined within its narrow parameters, is not to be tolerated. In the 33 years since Kopay announced his homosexuality, not one active professional football player has followed suit.

After reading a series in the now-defunct Washington Star on gay athletes, the hypocrisy simply became too much for him. The stories had used anonymous sources, and Kopay felt that if an accurate portrayal of being gay in professional sports were to be written, it needed a face. That’s how he came to call the reporter, Lynn Rosellini (the daughter of former Washington governor Albert Rosellini, ’32, ’33), who wrote the series. He followed that interview by co-writing The David Kopay Story, his landmark autobiography, which made him a sought-after public speaker and an activist for gay rights.

“I really had no idea of just how big a thing it would become,” Kopay says, “or for how long I would have to continue to take all that hostility on. That hostility and self-loathing that had so been ingrained in me from my earliest years by the nuns and priests and my parents and society in general. When I first spoke out, you never saw any positive images of gay folks anywhere. Not that I was really identifying with gay folks at the time, but deep inside of course I really was.”

Kopay’s activism didn’t come as a surprise to those who know him intimately, though. “It’s in his nature to be outspoken on the things that matter to him,” says Joe Stewart, a production designer in Los Angeles and close friend of Kopay. “He’s a very intense person, and when he decides he wants to do something he’s very committed. He will see things through. He’s a straight-arrow person, and is never afraid to speak up for causes he believes in.”

***

Kopay has installed replicas of the UW’s famous Sylvan Theater columns in his back yard.

Whatever peace of mind Kopay may have purchased with his act of courage came at great cost. He still loves football, and had high hopes for a coaching career after retiring from the NFL. His announcement brought those to an end — he was effectively black-balled from the sport.

It also rocked his parents and siblings, who have struggled to come to terms with Kopay’s new identity. His mother, Marguerite, who is 94 and in poor health, now understands his decision to come out, Kopay says. Their relationship is on solid ground. Kopay’s father, Anton, who died in 1990, was never fully comfortable with his son’s homosexuality. And politics have estranged Kopay from his younger brother and sister — specifically their voting for George W. Bush in the 2004 election. He does, however, welcome his renewed relations with Tony, who during their youth served as a protector and mentor. The two speak often and visit each other regularly.

“David and I had our differences,” Tony Kopay says. “Mainly, my differences. A couple years ago, I invited him over for Christmas, and we’ve been on good terms since. Time passes, and time heals all wounds. I don’t want to remember all those other times.”

Kopay’s gift is by far the largest the Q Center has ever received, and its future impact is difficult to quantify. “It is incredibly meaningful,” says Q Center Director Jennifer Self, ‘05. “It enables us to do more fundraising, because it shows others that if an alum believes in the center and its mission enough to leave us $1 million, then this is an effort that’s worth supporting.” George Zeno, executive director of the University’s student life advancement, says he had spoken informally with Kopay for several years about becoming involved with the University. They came up with the idea for an endowment for the Q Center after Kopay read a story about a gay UW student who was homeless. Zeno says Kopay’s gift will be used mainly for support operations and scholarships.

“What he wanted to do was address the problems faced by some of the undergraduates on campus,” Zeno says. “In my conversations with him, he told me of his struggles with his identity while at the UW as a football player and in a macho fraternity.” Kopay was eager to help as soon as he could, and last year he wrote out a $10,000 scholarship check to the center, Zeno says.

“It took me a long time, too long, to accept myself as I really was.”

David Kopay

For Kopay, the endowment was no small gesture. His professional football career came to an end long before the big-money days of the NFL. His subsequent work — he recently retired from Linoleum City, a flooring company in the Los Angeles area that serves a Hollywood clientele — left him comfortable but hardly super-rich. The $1 million gift represents nearly half of his estate. Kopay says he felt an immense pull, a desire to provide the resources he never had as a student. He is not certain how at the moment, but he hopes to become more involved with the center, and to find other ways of helping the University. He’s interested in supporting research on Alzheimer’s Disease, an affliction that runs in his family.

Kopay’s time at the UW was marked by very public successes and private torments, and it’s no surprise that he needed a long time to sort out his feelings about the place. In recent years, he says, he has come to appreciate the University more and more for setting him on the path he would ultimately travel. That understanding, more than anything, is what brought him back, he says. Last September, during halftime of the Huskies’ game against Boise State, Kopay was recognized as a Husky Legend. The crowd roared as he crossed the field, and the moment resonated with him. He was one of them.

“There was really a long time where I was repulsed with who I was,” Kopay says. “It took me a long time, too long, to accept myself as I really was. And then to have to fight for others to come to understand and accept that we all have the same rights and responsibilities in this society — I’m hoping I can at least make a difference in that others in my position will have the freedom to be who they are, and to live the lives they want.”