Modern plagues Modern plagues Infectious diseases are back with a vengeance, UW experts warn

Once beaten by miracle drugs, infectious diseases are back and stronger than ever.

Once beaten by miracle drugs, infectious diseases are back and stronger than ever.

New York, 1990: Jim Henson, creator of the Muppets, dies suddenly from a virulent infection impervious to antibiotics.

Milwaukee, 1993: Approximately 400,000 people are sickened by an obscure intestinal parasite, cryptosporidium, contaminating the city’s water supply.

Seattle, 1994: Eleven children with chicken pox contract a “flesh eating” bacterial infection requiring most to have surgery to remove infected tissue.

Zaire, 1995: An estimated 244 people die from Ebola, a hemorrhagic fever virus for which there is no cure. It is spread through contact with bodily fluids and secretions.

Such headlines shouldn’t surprise us. Throughout history, infectious diseases have ravaged humanity, from the bubonic plague or “Black Death” of the 14th century to the “Spanish influenza” epidemic of the early 20th century.

But Americans have become complacent about infectious disease. First came the discovery of penicillin in 1929 (followed by other antibiotics); then the start of widespread vaccination programs and improved sanitation and education. The scourge of smallpox was wiped off the face of the Earth in 1977; we assumed others would follow.

In the 1980s, our world began to change. Newspaper headlines carried words like AIDS, E. coli, Lyme disease, Ebola, and Dengue. Today, infectious diseases are the third-leading cause of death among Americans; 3 million people throughout the world die each year from tuberculosis; some 80,000 Americans die from hospital-acquired infections.

Infectious diseases are survivors. They are invisible, capable of changing form, traveling great distances, disguising their identity and masking their power. For many today, the threat of infectious diseases, including AIDS, appears very new and very unsettling. People wonder: Will Ebola come to my town? Will antibiotics still cure my ailments?

Perhaps the most eminent threat to human health is the development of “superbugs”—bacteria resistant to antibiotics.

“The way the world works today there’s no such thing as an isolated place,” concedes Epidemiology Professor Ann Marie Kimball of the UW School of Public Health and Community Medicine. “A threat to the whole public health structure has been identified and when you get a complete picture of what this means, it’s very alarming.”

With such an array of possible threats to public health, the question on our minds is, “What new or emerging diseases should I be worried about?” According to UW experts from the newly formed Emerging Diseases Working Group, deadly, exotic diseases should not be your greatest worry.

Instead, perhaps the most eminent threat to human health is the development of “superbugs”—bacteria resistant to antibiotics. With the security blanket of antibiotics becoming threadbare, an estimated 13,000 deaths in the United States each year are attributed to antibiotic-resistant infections.

These infections include pneumonia, which is developing resistance to the mighty penicillin, as well as strains of tuberculosis, which are emerging as a health threat to AIDS patients. Even more disconcerting are strains of pneumococcus (linked to childhood ear infections, respiratory disease and meningitis) and drug resistant Staphylococcus aureus (which causes skin and blood infections), for which only one antibiotic, vancomycin, remains effective.

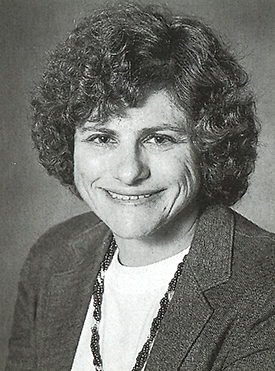

Marilyn Roberts

“Once this drug runs out there will be nothing left to cure these infections,” warns Pathobiology Professor Marilyn Roberts, who studies antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Improper use of antibiotics has contributed to this problem, she explains. Doctors prescribe the drugs for non-bacterial infections, such as colds, and patients fail to complete the full portion of their prescriptions, allowing drug-resistant genes to multiply. The use of antibiotics, such as in animal feed for chickens and sprayed on fruit and vegetables during food processing, further increases opportunities for resistant organisms to thrive.

“Some people think we’re crying wolf but we’re not,” says Roberts, who is a member of the UW Emerging Diseases Working Group. “The likelihood that an average American will be exposed to the Ebola virus is very low; the likelihood they’ll be exposed to antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the community sometime during their life is very high.”

Roberts says if trends continue, society will revert to pre-antibiotic times when infections were nothing to be taken lightly. A cut in the leg that became infected could lead to amputation. A severe case of tuberculosis might call for the removal of part of the infected lung tissue.

“Ten to 20 years ago if one drug failed we would have four or five other options,” Roberts explains. “More and more this is no longer the case.”

In response to the diminishing power of antibiotics, some companies are working on a new generation of these drugs. The Food and Drug Administration is considering measures to speed up the approval process. However it is unlikely that these new antibiotics can replace penicillin and other “miracle drugs,” Roberts notes. Because the new antibiotics are primarily variations of previous drugs, they, too, will eventually become ineffective.

A few smaller companies are beginning to look for totally new sources of “antimicrobials” in such places as the tropics and thermal vents in the ocean floor. And a few researchers, including some at the UW, are investigating the use of biotherapeutic agents—micro-organisms that fight back—as an alternative or supplement treatment for antibiotics. Discoveries in these areas may prove more effective in developing new classes of drugs, Roberts notes, but financial incentives need to be provided to encourage research.

In this new war on disease, UW researchers say, a new series of drugs is not going to be enough. They hope to develop a better understanding of these diseases through the UW Emerging Diseases Working Group. One of the first such groups in the nation, it unites more than 150 faculty members from the departments of medicine and public health with those from anthropology, zoology, geography, molecular biology, sociology and other units.

“We all need to learn about other fields in order to put our own work into perspective.”

Geography Professor Jonathan Mayer

“We all need to learn about other fields in order to put our own work into perspective,” says Geography Professor Jonathan Mayer, who is also an adjunct professor of medicine, family medicine and health services.

The initial push for this melding of minds was provided by Mayer and Kimball, who had begun discussing the idea while both were teaching courses in emerging diseases in their respective fields.

“When you think about it, we are all dealing with public health issues,” explains Mayer. “From economists and political scientists studying the impact of industrialization and civil unrest to sociologists and demographers studying the changes in people’s behavioral patterns and settlement habits, everyone has something important to offer.”

Kimball and Mayer agree the nation’s renewed focus on infectious diseases can be partly credited to a 1992 report, “Emerging Infections: Microbial Threats to Health in the United States,” issued by the Institute of Medicine. The report provided one of the first snapshots of the “big picture” of emerging diseases—a disheartening, yet constructive overview of the nation’s public health challenge.

“The evidence suggests … that humankind is beset by a greater variety of microbial pathogens than ever before,” the report warned. “Clearly, despite a great deal of progress in detecting, preventing and treating infectious diseases, we are a long way from eliminating the human health threats posed by bacteria, viruses, protozoans, helminths and fungi.”

According to Kimball, who has conducted health research in the Caribbean, Arab countries and South America, the report “promoted a change in thinking,” identifying and putting into perspective the global changes that are wreaking havoc on health care. Such challenges include:

* Human demographics and behavior — Changes in the way populations live, such as overcrowding in urban areas, can result in poor sanitation and hygiene, insufficient water supply and ecological damage in which some diseases, such as the Dengue virus, thrive. Sexual behavior and drug use have significantly contributed to the spread of HIV.

* Technology and industry — Hospitals are a prime source for the spread of disease and growth of bacterial resistance. An estimated 2 million people in the U.S. acquire infections during hospital stays. New medical technology may also contribute to this problem, especially in remote and/or underdeveloped areas where staff may not be trained in the correct use of these devices. Improper food processing and handling can contribute to bacterial diseases, such as the disastrous E. coli outbreak in western Washington due to undercooked hamburgers at Jack in the Box.

* Economic development and land use — Reforestation in the East Coast, along with increased traffic and suburbs encroaching on forested areas, led to the spread of Lyme disease. Global warming may also increase the spread of some micro-organisms, such as malaria in the future.

* International trade and commerce — A variety of diseases arrive in the U.S. through travelers, including Lassa Fever, a viral illness originating in Africa. Malaria has also been introduced to the U.S., most frequently in Florida and California, through infected migrant workers. International trade is also a source for disease transmission, most often from animals. Most recently, the linkage of “mad cow disease” in British cattle with a new strain of a similar human disease resulted in export bans on British beef.

* Changing microbes — Evolutionary changes allow microbes to adapt and change at a rapid rate. Microbes that survive vaccine or antibiotic treatments develop drug resistance.

* Human conflicts and poverty — Civil war and poverty contribute largely to the spread of diseases in the Third World. Diseases such as polio remain health threats in countries unable to afford vaccination programs. The growth of antibiotic resistance has contributed to the growing expense of drug treatments, leaving poorer nations without the funds to purchase alternative drugs.

Through the Emerging Diseases Working Group, faculty and students are finding ways to combine their pieces of knowledge to help tackle the global health puzzle. During the group’s most recent meeting, members identified a primary goal of research collaboration, both inside and outside the University. Group members are also spreading awareness of emerging diseases issues through presentations to the public. Some ideas include collaborations with the UW telecommunication projects for health surveillance, maintaining links with public health groups in the area and designing interdisciplinary projects.

Roberts says the working group is opening her eyes to a whole new world. “A year ago I didn’t know what medical geography was,” she relates. “A lot of us down in the trenches get very focused on our research without considering the broad array of disciplines it may be interconnected with. This group gives us a much broader perspective.”

After discussing her research on antibiotic-resistant bacteria with the working group, Roberts found new resources in the Department of Medicine and State Health Department.

Paralleling the research and public service challenges, the group is looking at the educational needs of students. There is a tremendous interest among undergraduate and graduate students in emerging diseases and public health issues. Members hope the work group will prompt the University to respond to this growing need. Currently they are working with the School of Public Health to develop an undergraduate minor in public health.

“We’re really concerned about fulfilling the educational needs of students in this area, because so many are expressing interest,” Mayer says. A new undergraduate course Mayer offered last quarter on geography and health filled up the first day of registration.

David Abernathy, a first-year Ph.D. student in medical geography, is one of the first students to see benefits from the campus working group. Involved in researching the spread of Dengue fever, Abernathy hopes to start collaborative research projects and is trying to organize a working group among students.

“I realized there are so many other things happening around campus that are interrelated; epidemiology, sociology, ecology ,” he says. “To try and consolidate all these things is really a challenge for me but I think it also leads to some great opportunities.”

In addition to educating students, the group also wants to reach the public about emerging diseases. For example, Kimball is currently working on a research project in Bangui, Central African Republic. The study involves educating the country’s traditional healers about the transmission of HIV and the need to use clean instruments and follow other rules of proper hygiene in their practice.

Education is just one piece of the battle plan, say UW experts. The war on disease should start locally—with strong local public health surveillance. Communities need to be able to recognize outbreaks and communicate with other jurisdictions. Increasing global communication and networking capabilities is vital. Businesses involved with trade and transportation also must address health safety issues.

A lack of funding remains one of the major obstacles. In a time where so many interests are competing for support, the fight for infectious diseases surveillance and research is becoming difficult. Some researchers, such as Roberts, believe it will take either a major outbreak or strong involvement and commitment from people in government to bring public health to the top of the list.

“There is little funding for improving control of emerging diseases and only so much can be done without it,” Roberts stresses.

Despite renewed efforts in the fight against emerging and reemerging diseases, “there’s no way of knowing what will hit next,” explains Mayer. “Whether it be Ebola, Dengue fever or a yet-unknown pathogen that emerges as a threat to human health, if we have a health system combining medical, social and biological forces with good surveillance and rapid response, we will be prepared to handle things effectively.”