From pain to poetry From pain to poetry From pain to poetry

Poet Jane Wong isn’t afraid to lay her emotions bare as she explores ways beyond the written page to reach audiences.

By Rachel Gallaher | Lead photo by Helene Christensen | November 19, 2021

Like many people, poet Jane Wong took up several new hobbies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Aside from writing and holding classes via Zoom—Wong, who received her Ph.D. from the UW in 2016, teaches courses in creative writing and literature at Western Washington University; she recently received tenure—she took up cooking and pottery, and is working on collaborative projects with other writers and creatives. She won’t say much about them, except that one revolves around seeds and the other involves making paper.

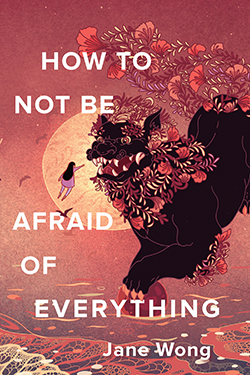

“I’m interested in losing this idea that something has to be ‘work,’ she said early this fall over a Zoom call from Bellingham, where she lives. “Currently, I want to do things that are fun and that surprise me—I want to put myself in a position where there’s potential to fail.” We’re chatting about a month before Wong’s second book of poetry, “How to Not Be Afraid of Everything” (Alice James Books), is set for publication, and it’s hard to imagine her failing at anything.

At 37, Wong is a noted figure in the world of poetry. Aside from her two books, she holds an M.F.A. in poetry from the University of Iowa and a doctorate in English from the UW. Her work has appeared in dozens of publications, and she has been awarded a handful of fellowships and residencies, including a scholarship through the prestigious U.S. Fulbright Program that allowed her to live in Hong Kong for a year. It was there that she started exploring the poetry as a form of expression.

But of all the awards and achievements she’s garnered, Wong credits the James W. Ray Distinguished Artist award for Washington artists as the most transformational. That grant allowed her to mount her first solo art show, “After Preparing the Altar, the Ghosts Feast Feverishly,” at Seattle’s Frye Art Museum in 2019. Integrating her written work with installations, the show, like her work, explored silenced histories, immigrant narratives, and intergenerational trauma.

Pieces from Jane Wong’s art installation at Seattle’s Frye Art Museum in 2019. (Photos by Jueqian Fang)

“I was between books at the time,” Wong recalls. Her first full-length collection, “Overpour” (Action Books) came out in 2016 and is rooted deeply in her personal experiences, including growing up in her family’s Chinese restaurant in New Jersey. (Wong was born in the United States, but her parents are both originally from China). “After the Frye show, I started thinking more deeply about sculptural work and performance,” she explains.

In October 2020, Wong participated in the UW’s Fall Convergence Festival, in which writers performed work with a focus on experimental translation. Wong presented her poem, “The Long Labors,” while cutting out the words of the poem from rice paper and folding them into dumplings as she read. She then cooked the dumplings and ate them. For her, that experience pushed her to look past the traditional author/audience divide and start thinking about new ways to engage with others through her work. “If I hadn’t done my exhibition at the Frye, I don’t think I would have ever moved beyond just standing up there and reading poems,” she says.

It’s a concept she plans to delve into further with the 2021-2022 Harvard University Woodberry Poetry Room Creative Fellowship and Grant she received along with poet and multimedia artist Diana Khoi Nguyen. The duo will be mounting a collaborative project titled “Radical Altars to Alter” to investigate the idea of building alter spaces to change the future. “I don’t want to overthink or over-plan it,” she says, but “there will be an installation along with a performance piece.”

In comparison with her first book, “How to Not Be Afraid of Everything” shows signs of a matured writer. It’s open and expressive; Wong is not afraid to freely express her emotions, including fear, heartache, and rage, in ways both nuanced and direct. “It’s a much more vulnerable, formally risky book,” she says. “I look at this idea of the ‘American Dream’ more closely and with a very critical, cutting eye, and look at it in relation to my family and what they suffered during China’s Great Leap Forward. In many ways, I’m speaking to my ancestors through this work.”

In comparison with her first book, “How to Not Be Afraid of Everything” shows signs of a matured writer. It’s open and expressive; Wong is not afraid to freely express her emotions, including fear, heartache, and rage, in ways both nuanced and direct. “It’s a much more vulnerable, formally risky book,” she says. “I look at this idea of the ‘American Dream’ more closely and with a very critical, cutting eye, and look at it in relation to my family and what they suffered during China’s Great Leap Forward. In many ways, I’m speaking to my ancestors through this work.”

She’s also speaking to a generation of women who are tired of being silenced, disrespected, and ignored, giving them permission to stand up and speak up for themselves—and their trauma. “Being an Asian American woman, I’m not supposed to be anything besides quiet,” she says. “I think people just expect me to be sweet. A lot of my rage is coming from that expectation that I’m not supposed to be angry—and that just makes me angrier!”

Currently, Wong is working on her third book of poetry, which she is writing to her ‘dream daughter,’ who she sees as around 15 years year old. “In contrast to my second book, this one feels happy and safe,” she says. “It’s an interesting progression… all I want to do these days is write things to tenderize all of that anger I’ve felt.”