Somewhere in the black hole of Japan’s powerful bureaucracy, self-effacing Yoshihiko Miyauchi, ’60, is considered by some as Public Enemy No. 1. As president of the Council for Promoting Regulatory Reform, which reports directly to the Japanese cabinet, and as a friend of Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi, this UW alumnus is known as “Mr. Deregulation.” He is the free market economy czar of Japan.

It’s not exactly the most glamorous nickname, but his reputation opens doors as harmony-loving Japan undergoes “Big Bang” financial liberalization intended to improve competition and accountability. “I wish we had a ‘Big Bang,’ ” Miyauchi says. “It’s more like a slow fizzle.”

No one argues with his credentials as Japan’s leading change agent. Sharp as a tack at 71 years old, Miyauchi is chairman and CEO of ORIX Corp., an $8 billion conglomerate with 15,000 employees providing a myriad of corporate financial services, automobile leasing (575,000 vehicles and counting), real estate, life insurance and investment banking services. Knowing the ins and outs of businesses as diverse as nursing homes, golf courses, autos, shipping and banking—as well as holding directorships on the boards of Fuji Xerox, Showa Shell Sekiyu and Sony, among others—Miyauchi has two essential traits that mean everything in Japan’s inner circle: credibility and trust.

Since founding what was originally called Oriental Leasing Company four years after earning his UW M.B.A., Miyauchi has expanded ORIX services to more than 23 countries. From India to Kazakhstan, the United States to China, ORIX has joint-ventured, bought and self-sowed businesses now worth $63 billion and reaping $1 billion in annual income. No wonder a smiling Miyauchi was anointed “Japan’s Most Powerful CEO” on the December 2005 cover of Forbes Japan.

To keep the ORIX brand a household name in Japan, Miyauchi had the foresight 18 years ago to buy a major league baseball team called the Braves, renamed the BlueWave and most recently the Buffaloes. In the BlueWave era, outfielder Ichiro Suzuki collected a record-breaking 210 hits in his first full season, earned seven batting titles and twice led the team to the Japan Series. Now playing with the Seattle Mariners, Ichiro continues his dominance, winning five Gold Gloves and earning six consecutive All-Star Game appearances.

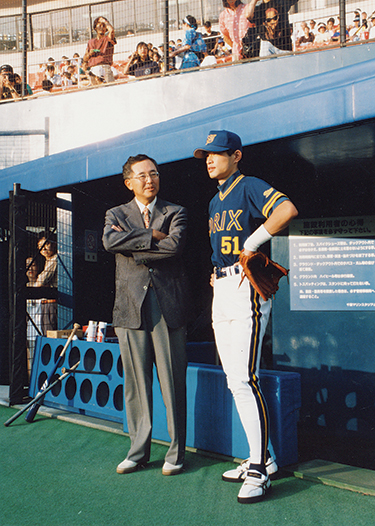

Yoshihiko Miyauchi chats with Ichiro Suzuki, then with the ORIX BlueWave. When his company owned the BlueWave, Miyauchi nurtured the all-star player’s career in Japan.

Miyauchi tracks Ichiro’s progress with avuncular pride. Lining the glass shelves of his spacious Tokyo office are many photos of the superstar. “This one here with my wife was taken last year,” he reminisces before picking up a black wooden bat about the size of a samurai’s sword, clearly used and signed with a silver pen by Ichiro. Every winter the slugger returns to Kobe, gladly accepting Miyauchi’s long-standing invitation to use the Buffaloes’ training facilities and touch base with his mother country.

Miyauchi knows what it’s like to be a foreigner in Seattle. In 1958 he arrived via Vancouver, B.C., to study business at the UW. Before leaving Japan, he learned his first lesson in international relations. When applying for a visa at the Canadian Embassy, he was perplexed by a world map in the waiting room. “That’s where I found out,” he says with a laugh, “that Canada was the center of the world.”

Finally landing on American soil, Miyauchi compared it to “paradise.” It was not the expansive vistas of the West that impressed him. “The highways were amazing,” he says. “Everything was new and modern and automatic. I kept thinking how stupid Japan was to start a war against such a rich country.” These were some of the first lessons that inspired his leadership and entrepreneurial flair. He absorbed the cultural values of the West and later blended them with his own Asian approach into a balanced force.

Prodded to attend the University of Washington by his father, who traded lumber in Seattle before the war, the impressionable, 22-year-old Miyauchi refused to comply with the Japanese proverb: the nail that sticks up gets hammered down. Despite his broken English, a lack of real world business experience and being the only Asian in his class, he landed a scholarship covering his full UW tuition. And more importantly, he met his future wife, Nobuko, in Seattle, while she was attending community college as an international student. “To this day,” Miyauchi says, “I owe a debt of gratitude to American society and the people of Washington for their generosity.”

“Men, women, Japanese, American, Indian, whoever. If you include diverse individuals on one team, they will create something new.”

Yoshihiko Miyauchi

Miyauchi’s ties to the University of Washington remain deep. His daughter studied art at UW and his son received his M.B.A. in 1995. Miyauchi also serves on the UW Business School Advisory Board and is one of President Mark Emmert’s key advisors for the Asian region.

Miyauchi brings to the University a global perspective and business acumen that value ideas over traditional norms. Take, for instance, the ceremonial distribution of business cards and bows before Japanese meetings. This everyday ritual sets the tone for who’s superior and inferior. “In the U.S.,” says Miyauchi, “when two people sit down, they start at zero.”

Another standout is Miyauchi’s tolerance for risk. “In a traditional Japanese corporation,” he says, “if you fail it’s the end of your life.” On the other hand, managers at ORIX are encouraged to swing away. “My job,” Miyauchi explains, “is to minimize loss by failure.”

Some may think that individualism and risk-taking contradict the Japanese concept of wa, or harmony, but Miyauchi believes in a strong sense of balance and symmetry created by teamwork.

Taking a page from the Japanese-revered business guru W. Edwards Deming, who preached to Japanese auto execs in the 1950s that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts, Miyauchi thinks one of the keys to ORIX’s success is putting different people in the same room. “Men, women, Japanese, American, Indian, whoever,” he says. “If you include diverse individuals on one team, they will create something new.”

The only area where Miyauchi allows go-go individualism is in the financial sector. These lone traders were largely responsible for ORIX’s whopping 82 percent increase in 2005 net income. Profits like these are raising eyebrows among Japan’s old bureaucratic guard. With the recent prosecutions of two financial high flyers, the reformists are taking a beating. As a result, one of Miyauchi’s deregulation goals, the breakup of telecommunications giant NTT, is looking like a long shot. That would be a shame, he says, because NTT’s analog technology inhibits changes brought about by digital technology and IT development.

Above all, Miyauchi is a defender of fair competition. He believes the free market, not the bureaucrats at MITI (Japan’s Ministry of Trade and Finance) or Japan Post (the postal service that manages in excess of $3.3 trillion in savings and insurance deposits), is the best economic decision maker. In an interview with Nikkei Venture, Miyauchi echoed Adam Smith’s playbook. “In a planned economy, bureaucrats plan, orchestrate and distribute,” he said. “In a market economy, buyers choose.”

But in Japan, as elsewhere, free-market capitalism is met with skepticism. Miyauchi laments that the United States is often the scapegoat for the ill effects of globalization. What would he do to cool things down? “I would concede much more,” says Miyauchi. “I would try to better understand cultural differences and not force countries into a U.S. way of thinking.” Sounding more like an elder statesman than a business executive, Miyauchi is definitive. “That’s the only way we can have peace.”