The year was 1970. America was in the thick of the Vietnam War, and students at the University of Washington—and all across the nation—were pushing for change. Students were up in arms about the war and fed up with racial injustice.

“You have to go back in time and imagine,” says Cliff Noonan, ’72, a communication major who transferred from San Francisco to the UW, where his father was a teacher in the ROTC program. “There were student activities and protests and all these things going on, and none of that information was getting to the students; it just wasn’t being processed. The only thing the UW had was The Daily, and I had worked at some stations back in California that were interviewing people from the Black Panthers; people who were very active in movements back in those days,” he says. “I felt that the students needed an outlet, a voice.”

More specifically, Noonan felt the UW needed a student-run radio station. One where they could get much-needed firsthand experience that could lead to a future in the broadcast field. The cry for more practical experience was shared by Brent Wilcox, ’74, John Kean, ’72, and Tory Fiedler, ’72. They joined with Noonan to bring their vision to life.

“We got into it with a lot of hope and no backing, and luckily, we were able to present the idea in such a way that the dean and the Board of Regents could see it as an educational advancement,” says Noonan. The deal? If the students could get the station licensed, the University would back it. “That’s all we needed to hear,” says Noonan. “We had to petition the Federal Communications Commission in Washington, D.C., and we had to find a space on the dial.” The students found a Canadian treaty channel at 90.5 FM that didn’t quite reach all the way down to Seattle and wrote to the commission, pleading to piggyback on top of that particular frequency.

As the clock ticked by, the students settled into the roles they would handle at the radio station. Kean spearheaded communications with the University and the FCC. Wilcox became the go-to engineering guy. Fiedler, who worked at The Daily, took on the role of news director, even getting an Associated Press wire newsfeed approved. Noonan worked his entertainment industry contacts in California, and began to build a music library. “I started writing letters to Columbia Records and a few other labels to try to get them to send us recordings from their young, up-and-coming artists,” he says. Most of the vinyl he received featured unknown artists—the eventual hallmark of KCMU/KEXP.

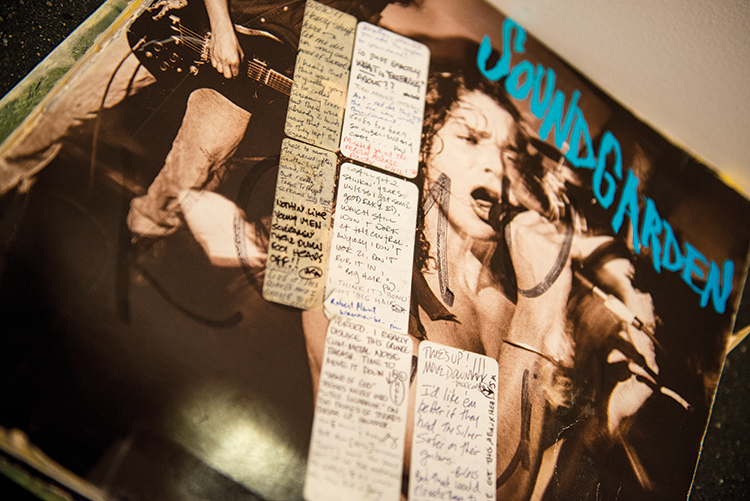

DJ notes on an album cover at KEXP.

A room on the third floor of the Communication Building had the bones to become a broadcast studio—if only they could find the equipment. “One day I went out to Nathan Hale High School, which, believe it or not, actually had a radio station going for its students,” Noonan says. “They were upgrading their transmitter, and I was able to convince them to give us their old one so at least we’d have something to power up if we ever got the thing approved.” He also picked up some old turntables from a radio station halfway to Canada.

They had the pieces, and thanks to a $2,500 grant from the Board of Regents, they had a powered transmitter, too, placed atop McMahon Hall. “It was a wonderful 10-watt transmitter that could broadcast all of 20 miles. It covered all of Lake Washington—the fish had good sound,” says Noonan, laughing. “Looking back,” Wilcox recalls, “it’s amazing it actually worked. We worried about it intensely.”

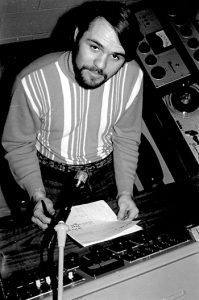

Brent Wilcox, ’74

It took the four students well over a year to transform the space that would eventually become the home of KCMU, named for the Communication Building. “You never saw four happier students than the day we got a letter from the FCC saying we were approved at that particular frequency. We went in thinking we could get it, but we weren’t sure,” says Noonan. “We’re talking about four students who had an idea and literally built a radio station from the ground up.”

Noonan had the honor of hosting the first broadcast. “I’m on the microphone going, ‘Is anybody there? Hello!’ I had been on the air for about two hours, and I actually got a phone call from somebody across Lake Washington and he said ‘Bro, this is great! Love your music! I have no idea who that artist was, but it was wonderful,’” says Noonan. “I hung up the phone and said, ‘God, somebody can actually hear us,’ and that was a real excitement. It gave me goose bumps that we could actually get it done.”

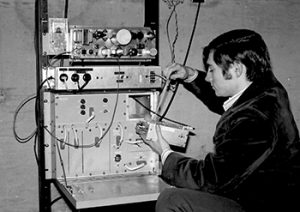

Cliff Noonan, ’72

The station grew slowly. Wilcox remembers times when he’d “work all night on a turntable that wouldn’t run at a constant speed, and I’d come home just in time to shower and go back to school and my dad would say, ‘And you’re getting paid how much for this?’” The four founders were devoted to the station, but graduation was fast approaching.

The University promised to keep KCMU alive, but the four students had no idea in what fashion. Noonan graduated and moved to California to start his career in broadcasting. “I was able to walk away with some satisfaction thinking, ‘Well, if it survives, at least there’s some groundwork.’” He didn’t really think about the station for 15 years or so, until someone mentioned a “really cool” radio station up in Seattle that he had to check out. That was in the late 1980s. Before the Internet, before streaming, the only way for him to hear the station was to physically get on a plane, fly to Seattle and check it out.

By then, the station had garnered acclaim from Billboard magazine, which touted KCMU as “one of the most influential commercial-free stations in the country.” The signal strength had grown from 10 watts to 400—enough to broadcast the signal beyond campus. Members of Soundgarden and Mudhoney moonlighted as volunteer DJs, playing everything from indie rock to hip-hop. Just a few years later, Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain would knock on the station’s door, with the demo for the grunge band’s premiere single, “Love Buzz,” in hand. It was KCMU, after all, that first played Nirvana’s debut album “Bleach” on the air. KCMU had gone from a “chewing-gum-and-barbed-wire station,” says Wilcox, to a “full-fledged world leader in new music.” KCMU continued to expand its programming, hiring full-time paid DJs. They moved to a new, larger home in the basement of Kane Hall.

John Kean, ’72

That’s when Kevin Cole, now KEXP’s senior director of programming and host of “The Afternoon Show,” got involved. Cole moved from Minneapolis to Seattle in 1998 to help Amazon.com launch its first product line after books: music. He’d spent his entire adult life in that sphere, starting and managing record stores; spinning as the house DJ at Minneapolis’ famed First Avenue Nightclub; launching his own radio station. His love of music led him to volunteer at KCMU, hosting a show on Sunday afternoons. “It was a typical college and community station—a group of insanely passionate music and radio lovers making the best out of the gear, equipment and resources it had,” recalls Cole. “There wasn’t really a studio for bands to play in, so on the few occasions someone would play live, they usually gathered around the guest microphone in the DJ booth with their backs pressed up against the wall. It was scrappy!”

That all changed when, in 2001, KCMU partnered with Paul Allen’s Experience Music Project, relocated to Dexter Avenue and was renamed KEXP. “[That move] really ushered in a new era of public service for the station—an era built on the foundation of the “wide and deep” programming philosophy of KCMU, and expanding on that philosophy and expanding as an organization,” says Cole. At that time, KEXP’s mission was to enrich people’s lives by applying technology to enhance the listening experience. In the following decade, KEXP was the first station to provide an uncompressed CD-quality stream online. The station developed real-time playlists, so the listener could see what was playing as opposed to waiting for the DJ to announce the set. It created a 14-day streaming archive, provided full-song podcasting and invested in video, so listeners could see the hundreds of bands that came through for a live set in their now-famous Christmas-light lit studio.

“Part of what sets KEXP apart is that our DJs have the freedom and responsibility to curate their own shows,” says Cole. That helped launch the careers of major artists like Nirvana, Vampire Weekend, Fleet Foxes, Of Monsters and Men, The Head and The Heart, The Lumineers, Alt-J, Courtney Barnett and Macklemore & Ryan Lewis—just to name a few. “It’s cool when an artist we play first breaks out in a big way, achieving superstardom or becoming part of the cultural zeitgeist, but like parents, we’re equally proud of all the artists we’ve played first and nurtured,” says Cole.

And now that the station has settled into a new studio at the Seattle Center—its first broadcast was Dec. 9, 2015—KEXP will reach an entirely new level of connectedness when it opens to the public on April 16. “When we were at Dexter and Denny, pretty much every day a listener from somewhere outside of Seattle would knock on the door and ask for a tour,” says Cole. “We love our connection with listeners, and we can’t wait to have the KEXP community come in and experience it in person.” The new home, which is nestled among Seattle arts staples such as the Experience Music Project, Seattle International Film Festival and the Vera Project (a music and arts center for youth), will allow visitors to sit in on in-studio performances and DJ-hosted salons.

“The four of us, we just didn’t know,” says Noonan. “We just didn’t know. We embarked on something, and it’s turned into exactly what I was hoping for: a station integrated with the community. KEXP seems to have hit a niche in the world of music and education, and it’s going to continue growing and expanding in that area with the new home. I’m excited as hell about it.”

KEXP’s new offices at the Seattle Center.

A sampling of KCMU/KEXP DJ alumni

- Mark Arm, ’85 (Green River, Mudhoney)

- Kim Thayll, ’84 (Soundgarden)

- Bruce Pavitt and Jonathan Poneman (Founders of Sub Pop Records)

- Faith Henschel, ’88 (VP Marketing, Capitol Records, Virgin Records)

- Scott Vanderpool (Room Nine, Chemistry Set, DJ at KZOK)

- Dow Constantine, ’85, ’87, ’92 (King County Executive)

- Kathy Fennessy (Music and film writer)

- Chris Knab (co-founder of 415 Records)