Embracing glory Embracing glory Embracing glory

Larry Owings scored the biggest upset in NCAA wrestling history and spent the rest of his life coming to terms with it.

By Mike Seely | Photos by Ron Wurzer | January 21, 2026

When Larry Owings was growing up in rural Oregon, everyone—his friends, his family, even his teachers—called him by the nickname “Porky.” They did this because he was overweight.

“Nowadays, they would call that bullying,” says Owings, now 75. “Back then, you just had to grin and take it. I can’t tell you how deep down inside I was hurting. It inspired me to say, ‘I’m gonna show you someday.’ “

Would he ever.

Owings had four older brothers, all of them state wrestling champs at Canby High School. Taking a gander at their baby brother in junior high, none of them expected Larry to wrestle at all, much less earn any kind of hardware. But a life-changing event—or occupation, rather—occurred in the summer before his freshman year.

“I went to work for an old Norwegian dairy farmer,” he recalls. “I hauled hundred-pound bales of hay for him all summer long. Before that, I worked on the farm picking berries, and I hated picking berries. There was no way I was not gonna do good in this job and go back to picking berries.”

Owings’ weight went from about 150 to 130 through the course of his sweaty vocation, and he also grew a couple of inches. In spite of his siblings’ doubts, he joined the Canby wrestling team and worked his way up to varsity at 123 pounds by the end of his freshman year. By the end of his high school career, he would win state championships in both the 136- and 141-pound weight divisions.

During his senior year, Owings was matched in a tournament with an Iowa State University sophomore named Dan Gable, who was undefeated and already an NCAA champion. Gable won their match rather easily, but Owings managed to score some points – quite a feat for anyone facing a man who would go down as the greatest amateur wrestler of all time.

After losing to Gable, Owings said he felt like he “had a score to settle.” Two years later, he’d get his chance.

Triumph, then turmoil

There were a lot of colleges interested in Owings’ wrestling services after high school, but the University of Washington won out.

“I didn’t go to Oregon State because my brothers had gone there,” he explains. “I went up to the U-Dub, beautiful campus, coach was very gung-ho. Jim Smith – he’s still alive, by the way. He’s 90 and lives in Lynnwood. I liked the school, I liked the coach. I wanted to go into architecture, and they had a great architecture program.”

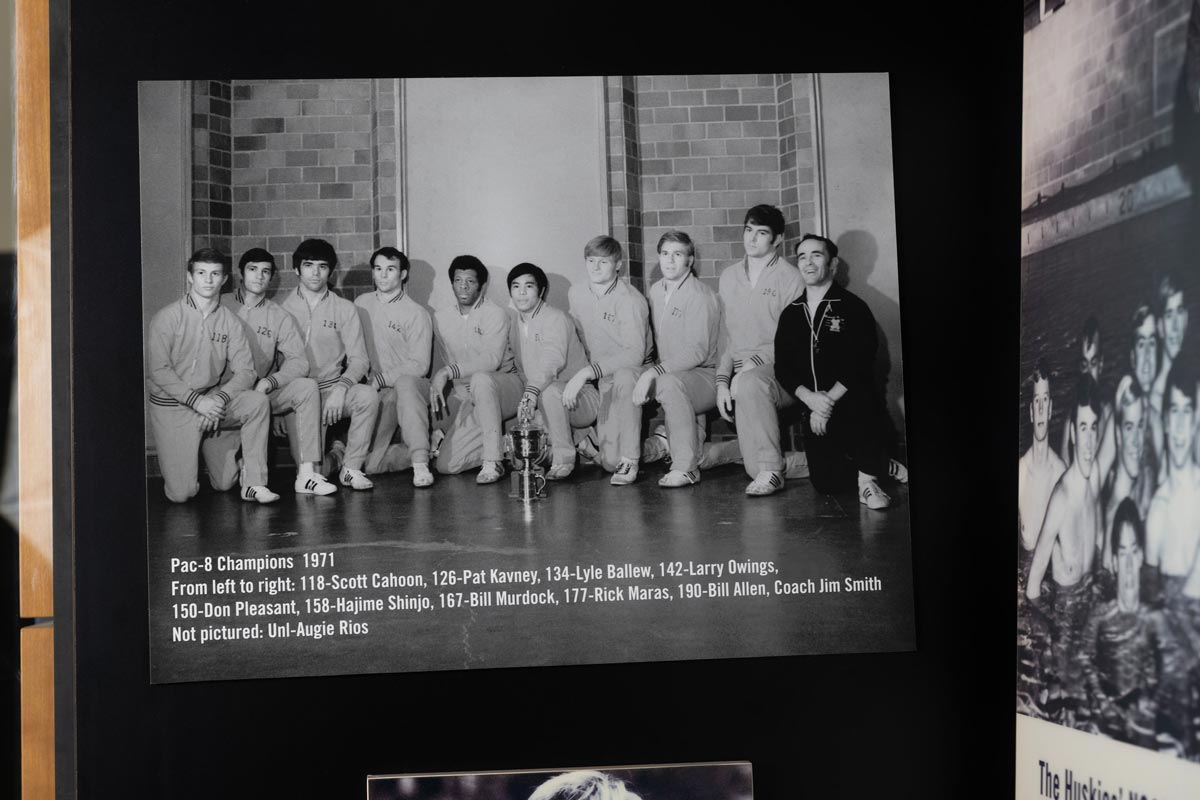

Owings, ’72, ’75, ’78, pursued an architecture degree for a quarter before he deemed it too difficult and switched to industrial education. Things on the mat went according to plan, however. By the time Owings was a sophomore, he was Pac-8 champion at 158 pounds with the 1970 NCAA tournament on the horizon.

But instead of competing in that weight class, Owings quickly shed 16 pounds so he could face Gable.

At the time, Gable boasted a record of 117-0. Counting high school, that mark stood at an unthinkable 181-0. Everyone viewed the tournament, which was held near Chicago on the Northwestern University campus, as Gable’s surefire coronation – everyone, that is, except for Owings, who told anyone who would listen that he thought he could beat the champ.

“I thought I had a little edge because whenever he wrestled anybody, he always pinned them,” says Owings. “He rarely had a full match. I thought, ‘I can push him,’ so my strategy going into that match was I was going to push him until he was exhausted. And that’s what happened in the third round. A lot of people didn’t know that I had wrestled him previously.”

Owings and Gable met in the NCAA finals. Owings got out to a shocking 7-2 lead and led 8-4 before Gable finally took a 10-9 lead in the third and final round when riding time – points awarded for a disparity in control over the match – was taken into account. But Gable was visibly tired and, having won the vast majority of his matches by takedown, got greedy in the final seconds.

Owings capitalized, dropping Gable to the mat via a devastating leg sweep and exposing his shoulders to earn four additional points. The 13-11 margin would hold. Owings had scored the biggest upset in wrestling, if not all of individual sports, of all time.

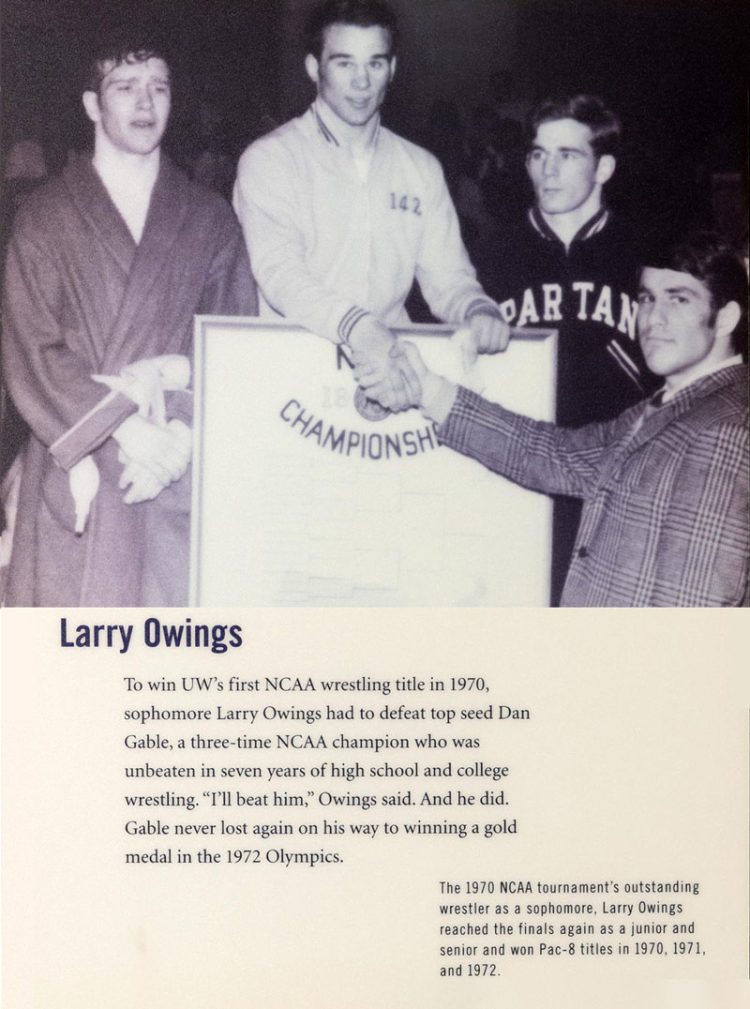

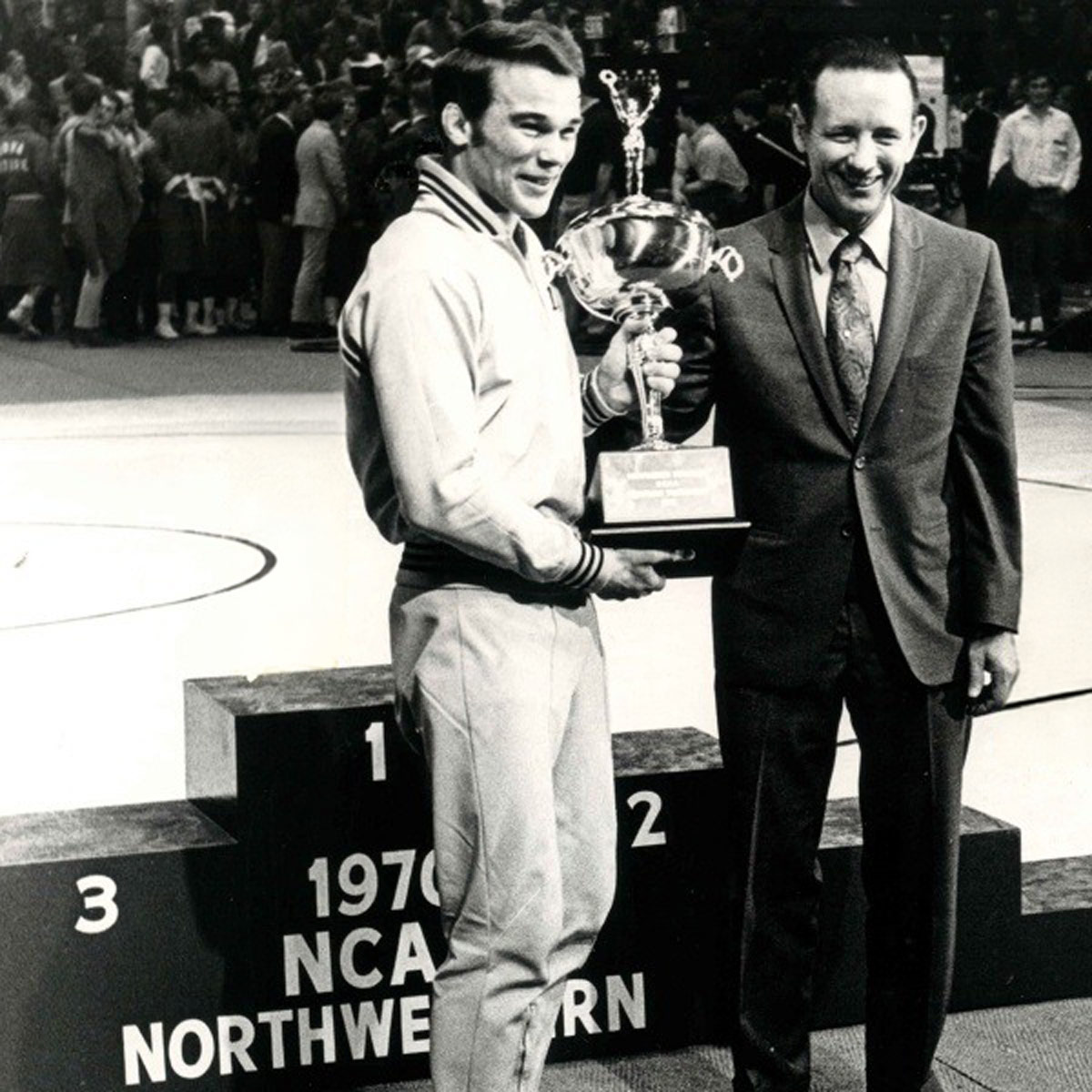

Larry Owings receives the NCAA championship trophy from legendary wrestling coach Grady Peninger after defeating Don Gable in front of a 9,000-person sold-out crowd on Northwestern University’s campus in Evanston, IL.

The years ahead were kind to Gable, who would go on to win the 1972 Olympics without yielding a single point and then become the greatest collegiate coach of all time at the University of Iowa. As for Owings, he got married during his junior year. While this proved somewhat detrimental to his wrestling career and the marriage ultimately unraveled, he was NCAA runner-up in his junior and senior years and finished with a career record of 87-4.

That record doesn’t include the third and final time Owings wrestled Gable at the 1972 Olympic Trials, where Gable would go on to avenge his 1970 loss in convincing fashion.

“When I beat Dan Gable, I went from a nobody to a celebrity,” Owings recalls. “It was something I wasn’t accustomed to and something I didn’t necessarily relish. I became the top dog, and everybody was shooting for me. I didn’t like that. I’m much more introverted. I like to be the quiet guy that comes in and slips up on somebody.

“I was tired of the monkey being on my back and thought, ‘I’ll just go out and wrestle Dan Gable, he’ll beat me, and everybody will leave me alone.’ All of that happened, but people didn’t leave me alone.”

“My attitude was the problem all along. Once I changed that and embraced what had happened, I felt better myself and helped a lot of people.”

Larry Owings

The Hall beckons

Owings plied his craft quietly in the Pacific Northwest as an educator, including stints as a shop teacher and head wrestling coach at West Seattle’s Chief Sealth High School, until 2003. Since remarried, he moved back to near his boyhood home in Oregon and began to experience a change of heart about the 33-year-old accomplishment that defined him in the eyes of many.

“I just thought to myself, ‘This is never gonna go away. God gave me this talent of wrestling and here I am trying to run away from it and hide. We’re gonna stop doing that, we’re gonna embrace it and start sharing with other kids,” Owings says. “My attitude was the problem all along. Once I changed that and embraced what had happened, I felt better myself and helped a lot of people.”

Owings kept working with young wrestlers, something he does to this day. He still dons the headgear and gets on the mat to show them proper technique, something he hopes to do until he’s 80.

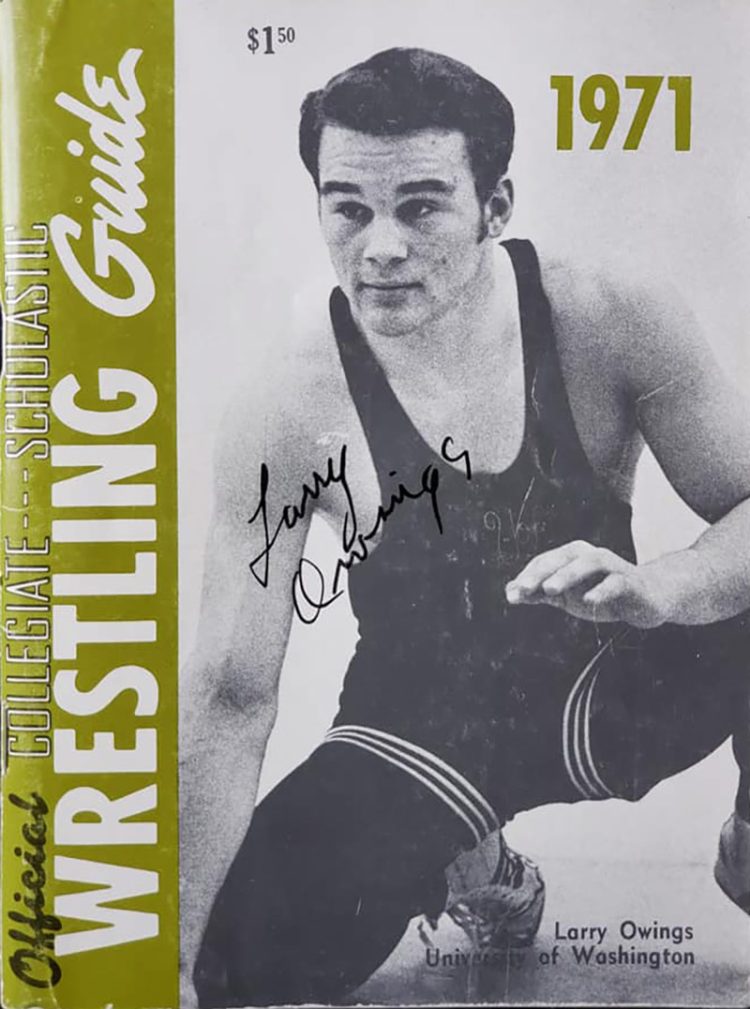

- Signed issue of the 1971 Collegiate Scholastic Wrestling Guide owned by Travis Bonneau, via Facebook.

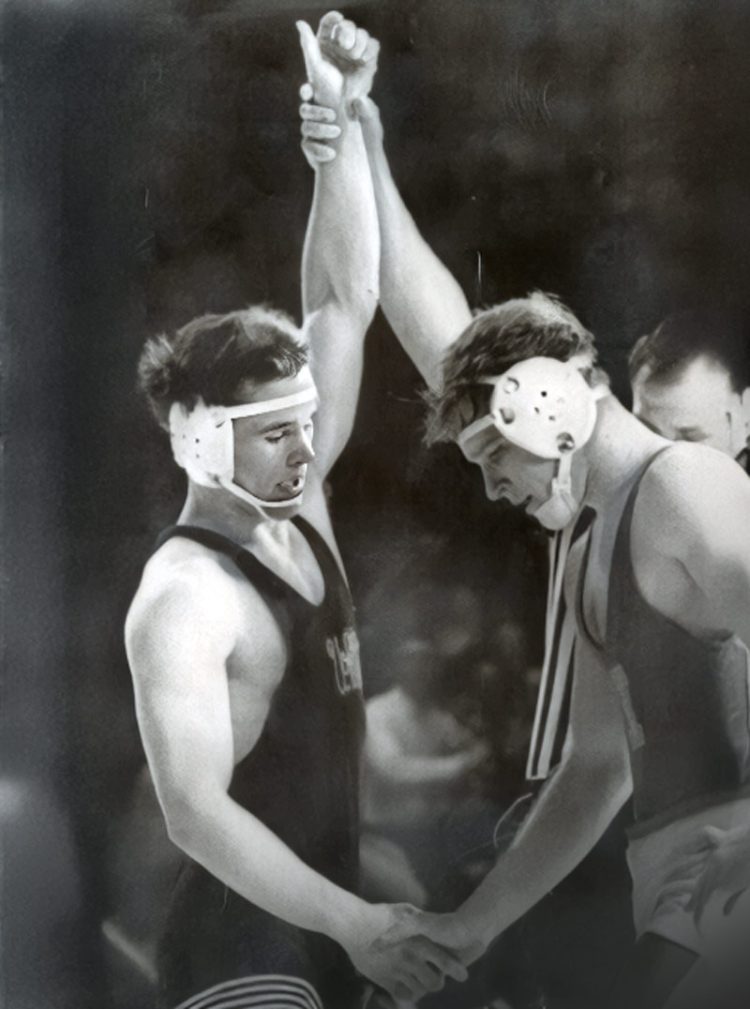

- Dan Gable shakes Larry Owings’ hand after their 1971 match.

Considering he wrestled in the most famous match in NCAA history and spent the rest of his collegiate career proving it was no fluke, it might come as a surprise that Owings has yet to be inducted into the National Wrestling Hall of Fame in Stillwater, Oklahoma. The fact that UW shuttered its program in the 1980s – it’s since been resurrected as a club sport – hasn’t helped his cause, nor has the humble lifestyle he has chosen to live in an out-of-the-way corner of the country.

But Owings, who says he’s stayed friendly, if not chummy, with Gable over the years, has many staunch advocates, and a movement is now afoot to get the man the recognition he’s presumably due.

“He’s a legend,” says Hall of Famer Randall Tomaras, who grew up in Bellingham and has penned a letter of support on Owings’ behalf. “A lot of the people only remember that one match. They say he was a one-time wonder. No, he wasn’t. He was in the NCAA Finals three times.”

“He gave American wrestling its greatest story,” wrote Jim Kalin in one of his columns for Amateur Wrestling News. “Ask 100 wrestling fans who Larry Owings is, and all know. Not so with plenty of National Wrestling Hall of Fame Distinguished Members, many who have never won an Olympic gold medal or NCAA title. No wrestler has matched Owings’ single moment and season. Isn’t that alone worthy of his induction into the Hall of Fame?”

Owings believes it is.

“I probably belong in the Hall of Fame,” Owings says. “There are several people in the Hall of Fame that I’ve beaten. To me, that’s gonna be probably the greatest honor you can achieve in United States wrestling. Waiting this long, it might mean more to me.”