Keister took on several jobs: He wrote album reviews, crafted culture pieces and once penned a story on Elvis impersonators. He even distributed the paper downtown, he says. “Once a month, I’d have to deliver to all the clubs, and my friends would come along. In one night, we could see every performance in town.”

The staff were experts in many genres: blues, folk, Caribbean, hip-hop and jazz. A 1982 feature highlighted the studio album “Kenny G.” In the story, a young Kenneth Gorelick credits his UW music professor Roy Cummings with finding him gigs and putting him on the path to be a professional musician. Otherwise, he might have followed his accounting degree to a very different career.

But when The Rocket started, Seattle didn’t have much of its own music to celebrate. In the June 1984 issue, Keister penned “Who’s Killing Seattle Rock and Roll?” He bemoaned the lackluster scene and questioned why the area’s few talented musicians never found fans outside of the city. He wondered if people would rather sit in well-lit coffee shops sipping strong coffee than on “ripped vinyl benches” while a “poorly mixed sound system blasts out feedback at levels above the threshold of pain.” Also, the city of the early ’80s was rife with cover bands—a genre The Rocket’s staff had no interest in critiquing or celebrating.

But it was about to get interesting.

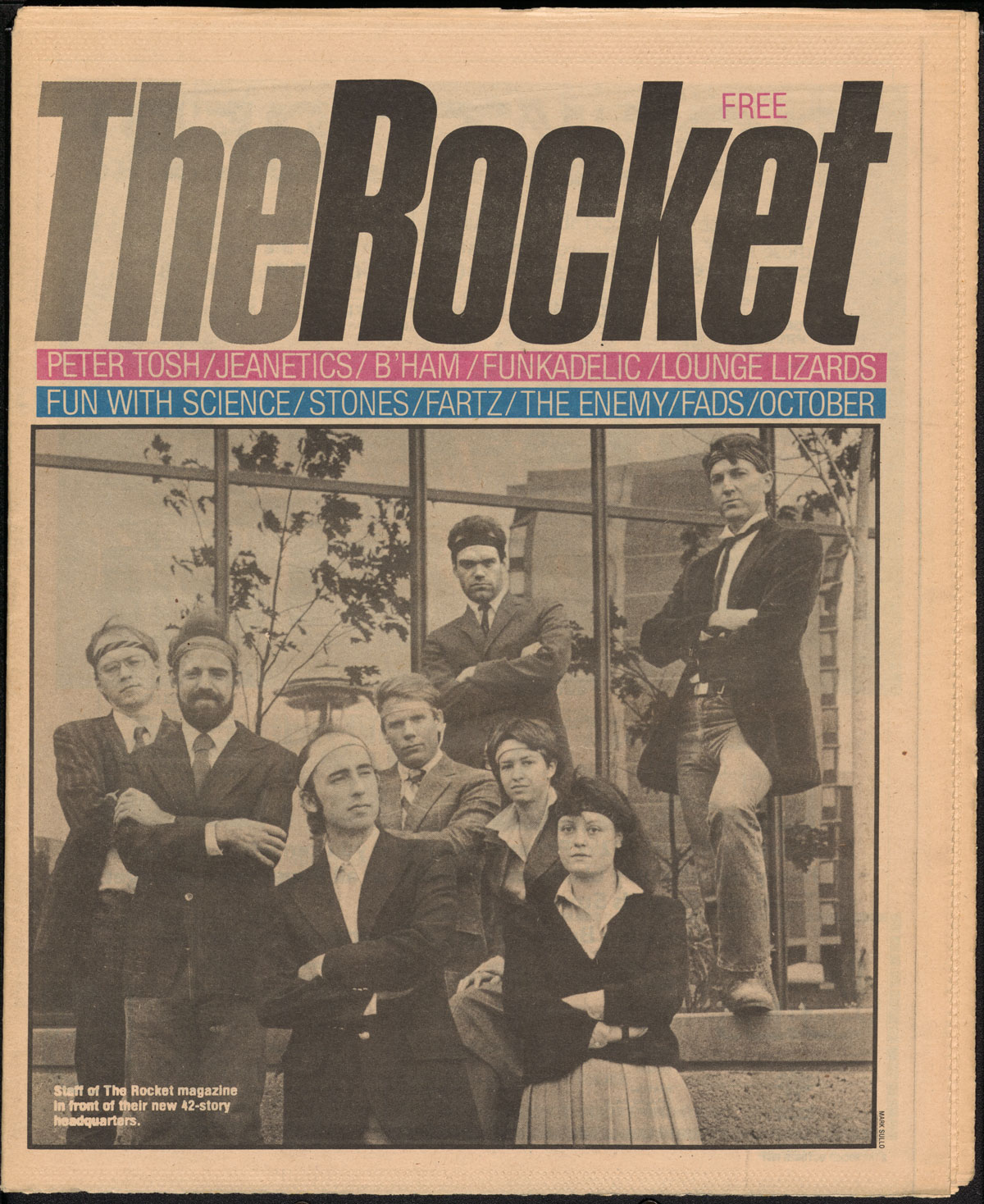

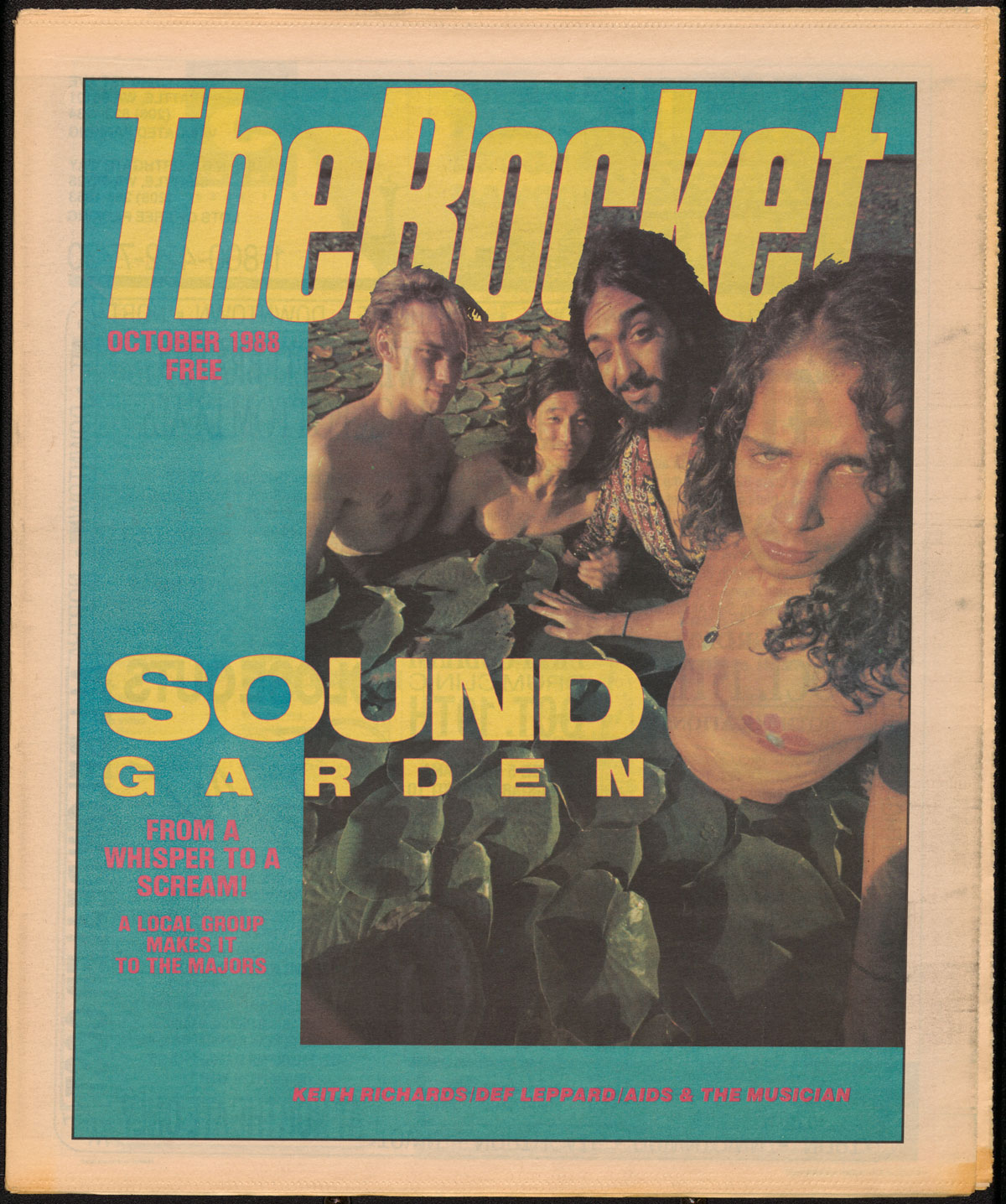

There were two eras of The Rocket, says Cross. From 1979 until 1986, the freshest music to hit the city flew into Sea-Tac, did an interview with The Rocket, played a gig or two and moved on down the coast. Because of the polar route from London to Seattle, the city was often the first stop on a West Coast tour and The Rocket was one of the first U.S. periodicals to cover bands like The Clash and Def Leppard. But after 1986, right when Cross mortgaged his house to buy the newspaper and become publisher, “the music scene starts taking off,” he says. Inspired by punk and rock but smarter, slower, darker and deeper, the emerging Seattle music was gritty, sludgy, distorted. More philosophical. More socially conscious.

The community of journalists, musicians and producers was small enough that everyone knew one another. Photographer Peterson, for example, had been college roommates with Mark Arm, ’85, of Green River and Mudhoney. Jonathan Poneman, one of the founders of Sub Pop Records, worked as a DJ at the UW’s student-run radio station, KCMU. Musicians from the early bands went on to form new bands.

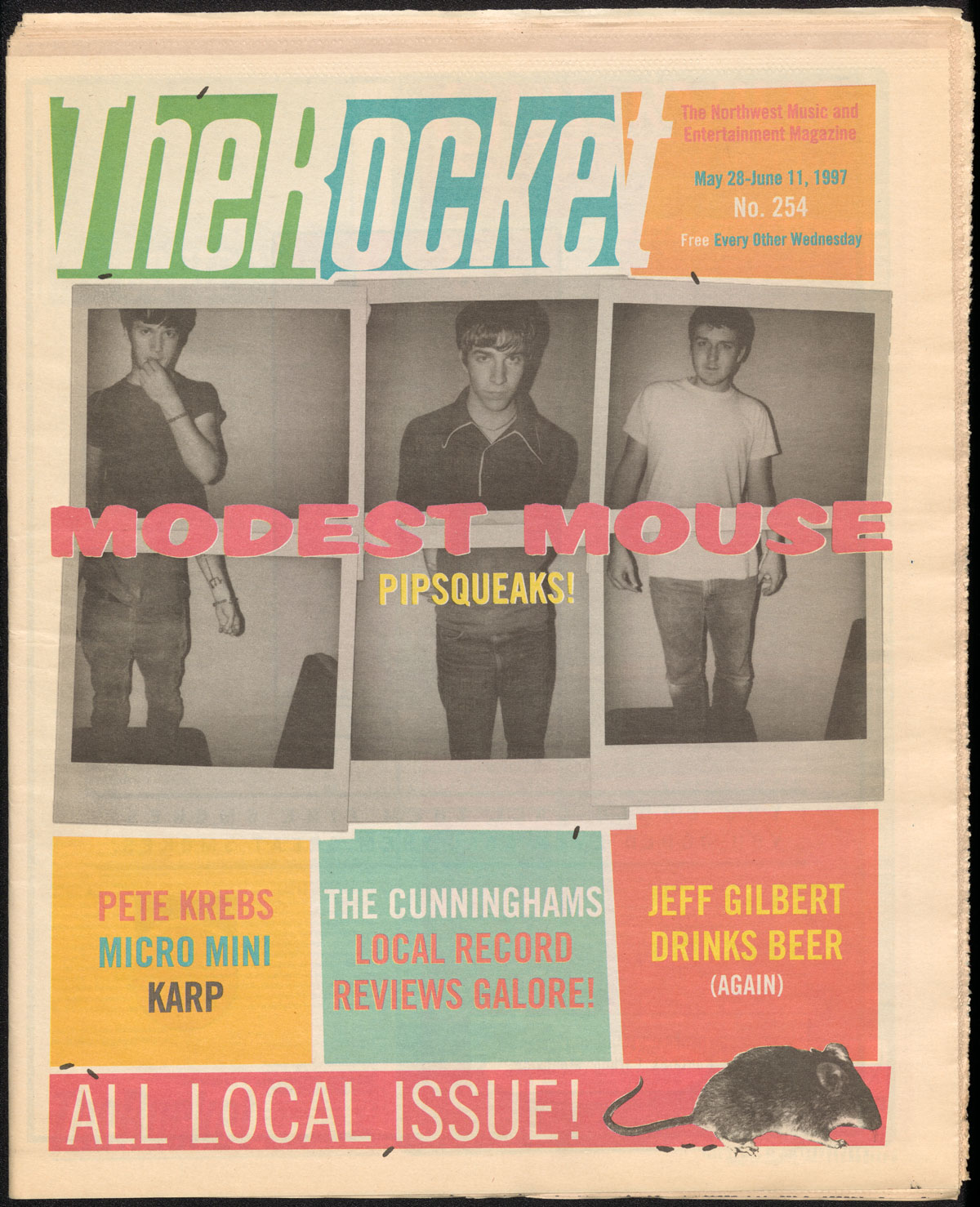

The late Chris Cornell of Soundgarden photographed by Charles Peterson

The Rocket staff had a moment of truth in 1989, when the paper hosted a concert at the Paramount to celebrate the first 10 years of the publication. Titled “Nine for the ’90s,” the December 29th event featured bands including Alice in Chains, The Posies, Love Battery and The Young Fresh Fellows. So many different local groups, so much talent, “it was very clear as the decade churned that something was happening in Seattle,” Cross says.

The Rocket was the first publication to feature Sir Mix-a-Lot, pictured here in a Charles Peterson photo in front of Dick’s Drive In.

The publication can also claim discovering Sir Mix-a-Lot. “He was living in Rainier Beach and grew up reading The Rocket,” Cross says. The rapper-songwriter often dropped by the offices with his demo cassettes. One day in 1985, a music writer gave one a listen and was blown away. In 1989, The Rocket rewarded Mix for his persistence and success with a full-color cover—again, shot by Charles Peterson. “There are a number of artists like that, where we were the first place they were written about,” Cross says.

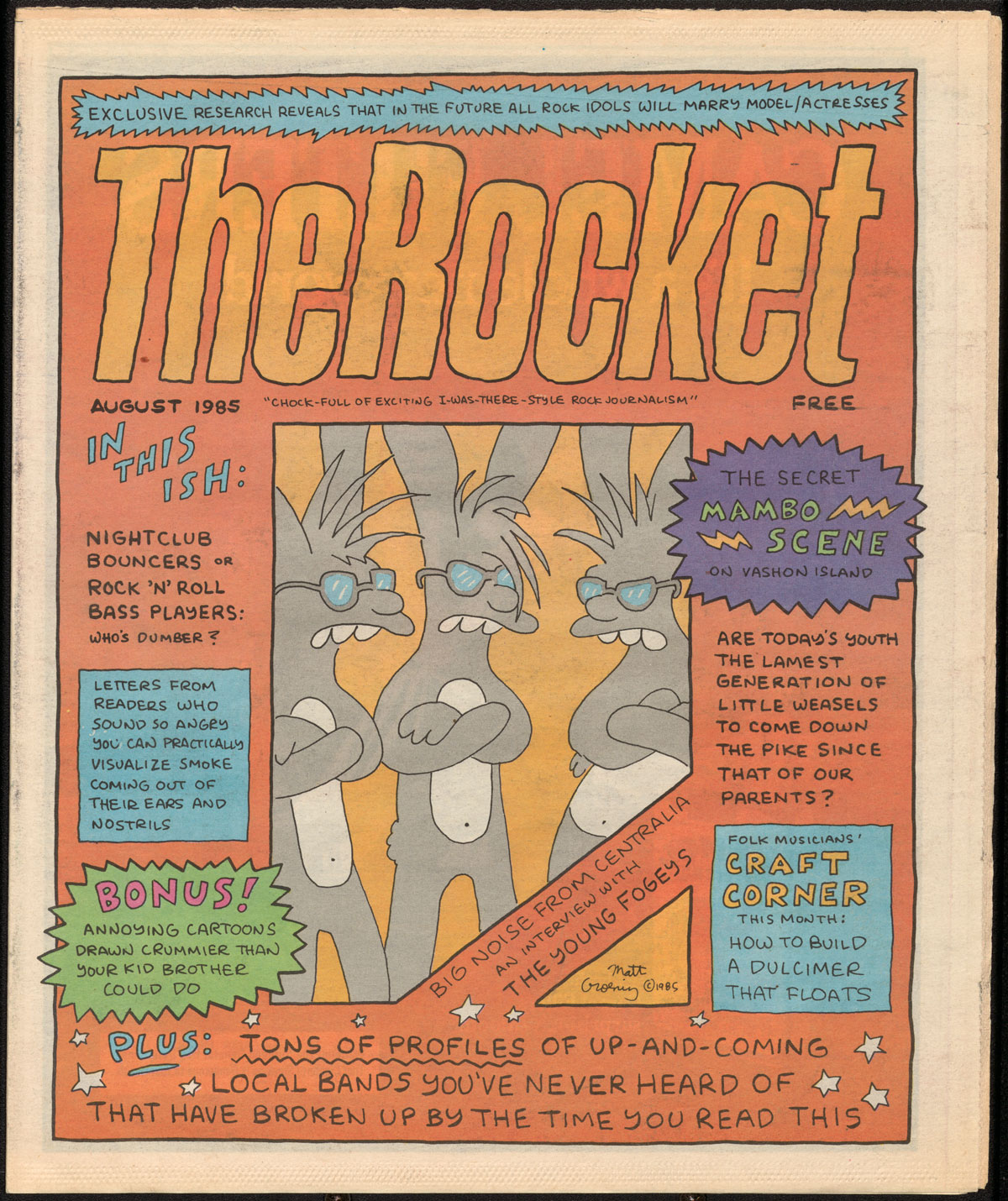

In the early years, The Rocket’s writers and editors had acted as if the vibrant music scene they dreamed of already existed, say both Cross and Keister. In a 2019 podcast interview, Michael Dougan, an illustrator for The Rocket, said, “Nothing was going on … it was just hair bands. There was no scene to write about.” What unfolded was like a Looney Toons gag, he said, “where the locomotive is going on a train track that doesn’t exist yet and the character is putting the train track down ahead of the locomotive in real time.”

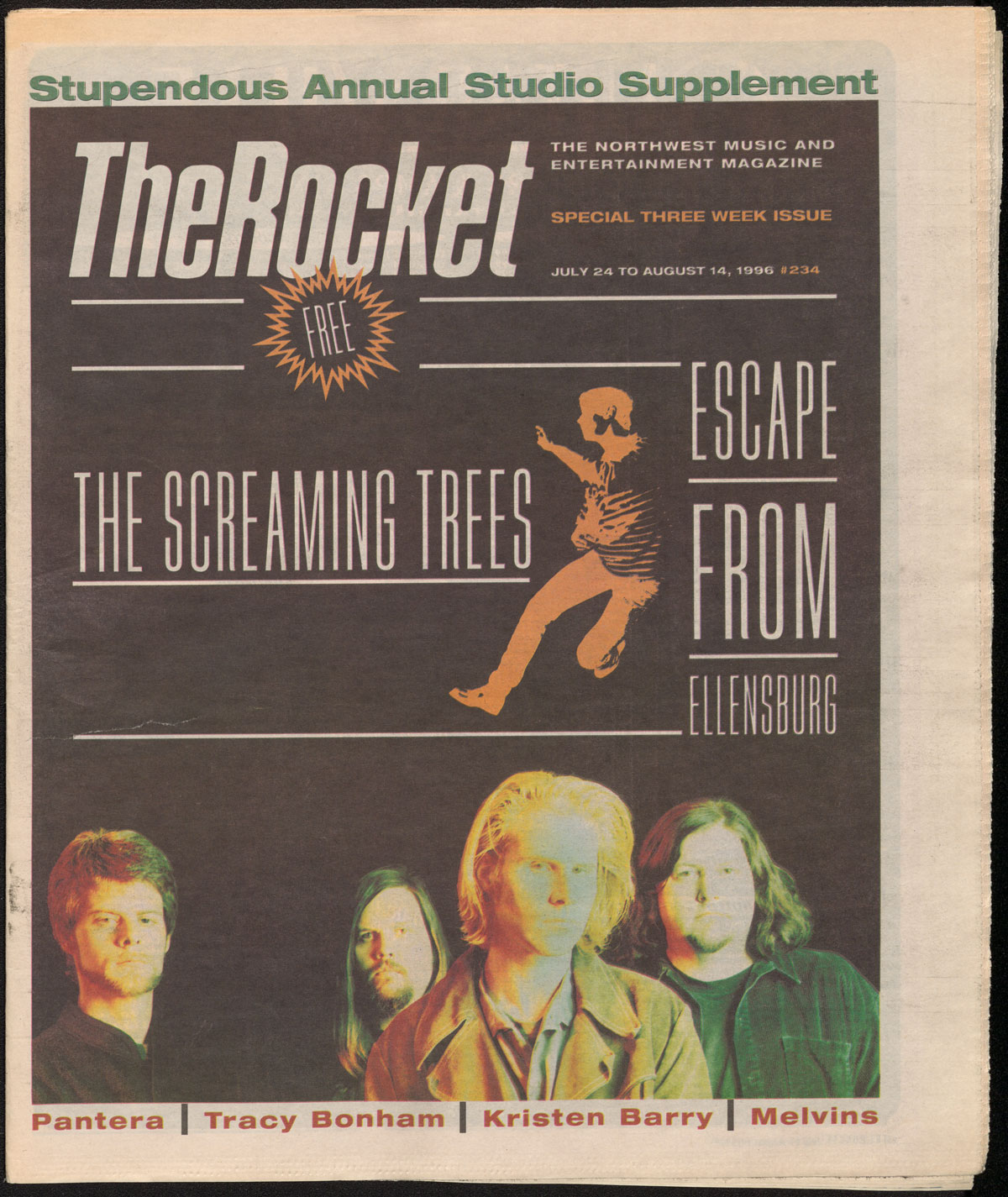

Under Cross’ ownership, The Rocket grew its circulation to nearly 150,000, showing up and inspiring new musical talent in cities like Aberdeen, Olympia, Bellingham and Ellensburg. It was like a local newsletter for emerging musicians and it nurtured what was just about to exist. “We wrote about it so much as if there was this magical Disneyland,” Cross says. “In a way, by selling that dream as if it were real, we gave these people something to believe in, and they made it happen.”

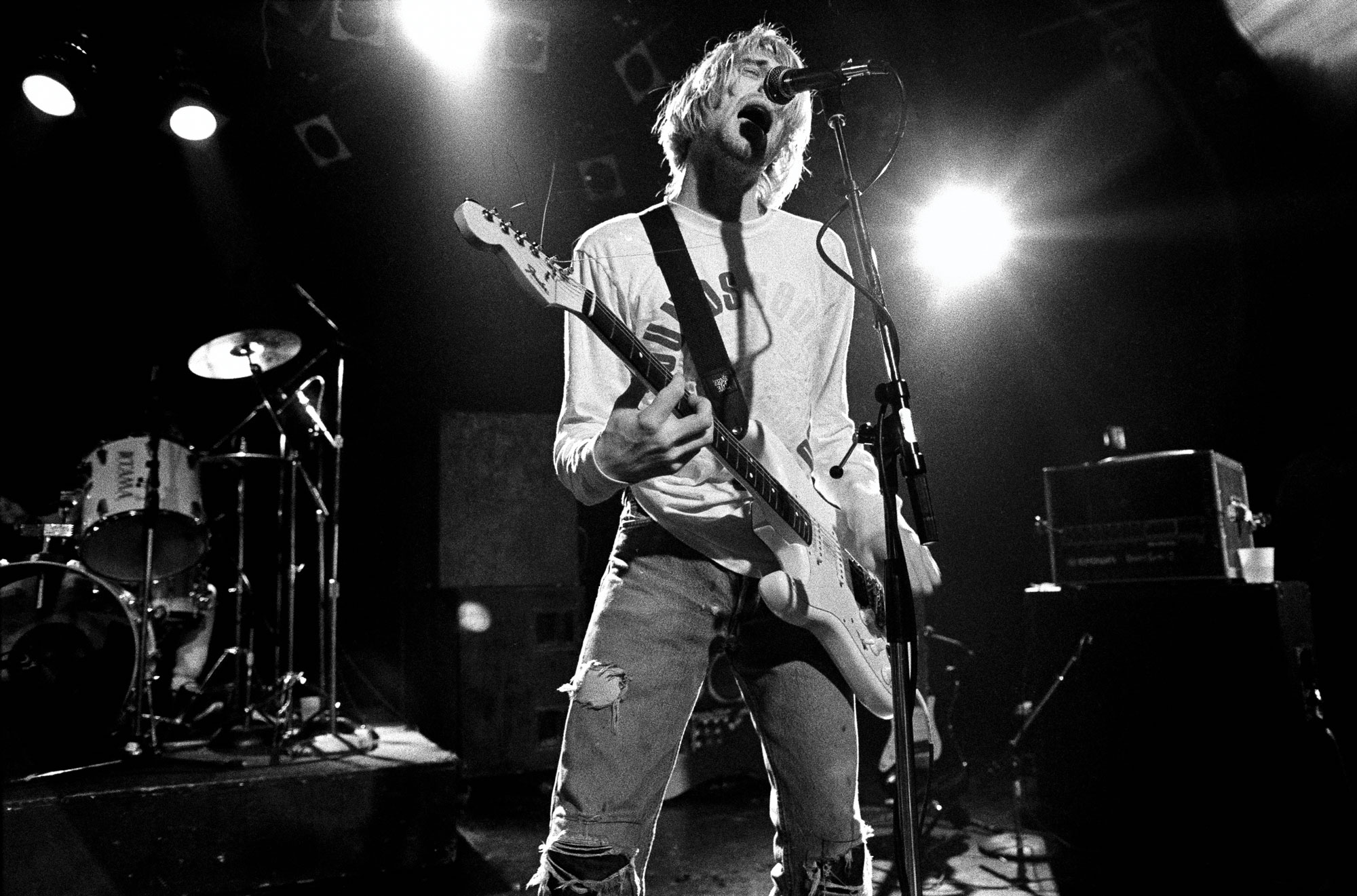

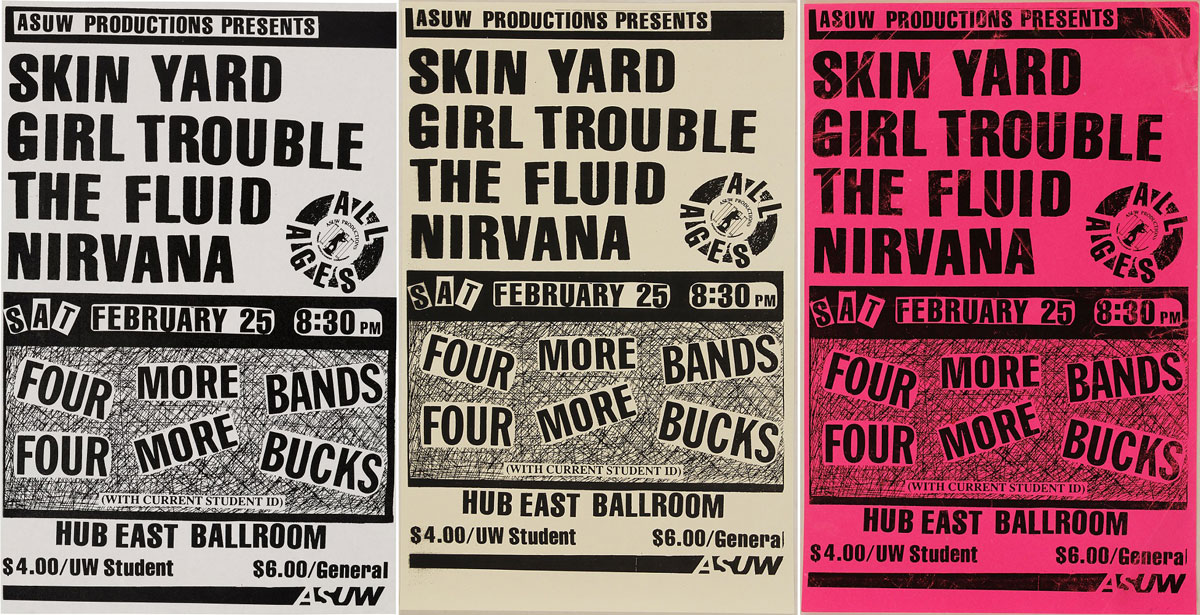

Local bands depended on The Rocket, says John Vallier, a UW ethnomusicologist and affiliate assistant professor. The musicians of the grunge movement—including Kurt Cobain—started reading it as teenagers, dreaming to someday be featured in its pages—or on its cover, he says. “I lived here in the ‘90s and played music,” Vallier says, listing off a few of his bands including Vishnu Secrets and Swell. They performed at venues like the Showbox, Speakeasy, The Crocodile, RCKNDY and the OK Hotel, and hoped The Rocket would provide good reviews. “We knew how important it was.”

The rest of the country finally took notice.

Grunge—by then it had a name—became mainstream around 1991, when Nirvana dropped “Nevermind” and the album went platinum. The grunge influence spread through fashion, politics and film. Director Cameron Crowe set the 1992 romantic comedy “Singles” in Seattle when grunge was at its peak. One of the characters, a musician played by Matt Dillon, gets slammed in a Rocket review. The byline you see in the clip is Sharon Knolle’s, ’88, who is now an entertainment reporter in Los Angeles.

One day a few years ago, Vallier asked Cross, who sold The Rocket in 1995, just before the national grunge scene started to decline and five years before the publication’s demise, to speak to his class. As they were discussing the evolution of the local music scene, the idea of digitizing all the issues of The Rocket came up. It was something Cross had been considering and Vallier knew it had to be done. To pair the newsmagazine’s content with the UW’s sound recordings of performances would be a boon to researchers and a gift to posterity, he says. “And as a teaching tool, it’s great to give students a sense of what life was like pre-internet.”

In addition to working with colleagues at UW Libraries, the project found a partner with the Washington State Library and funding from a Library of Congress grant and the National Endowment for the Humanities.

The archivists and librarians worried they might not be able to build a comprehensive collection. But Cross came through. He crowdsourced a complete run of the newspaper from friends, former coworkers and fans. People had held on to issues for 40 years and were driving by Cross’ house to drop them off.

The work of digitizing was challenging, says UW librarian Jessica Albano, “because of all the color they used and all the different fonts.”

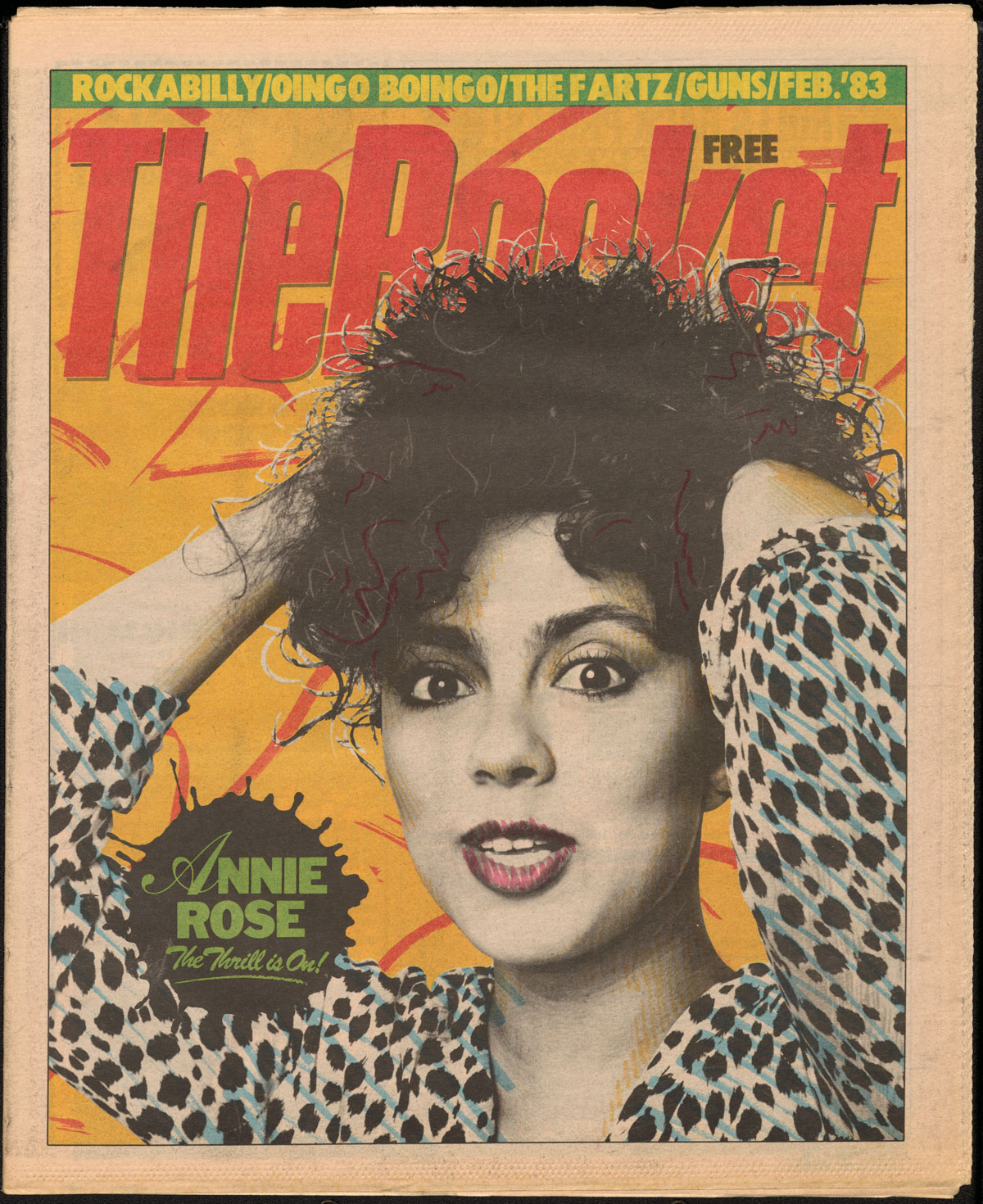

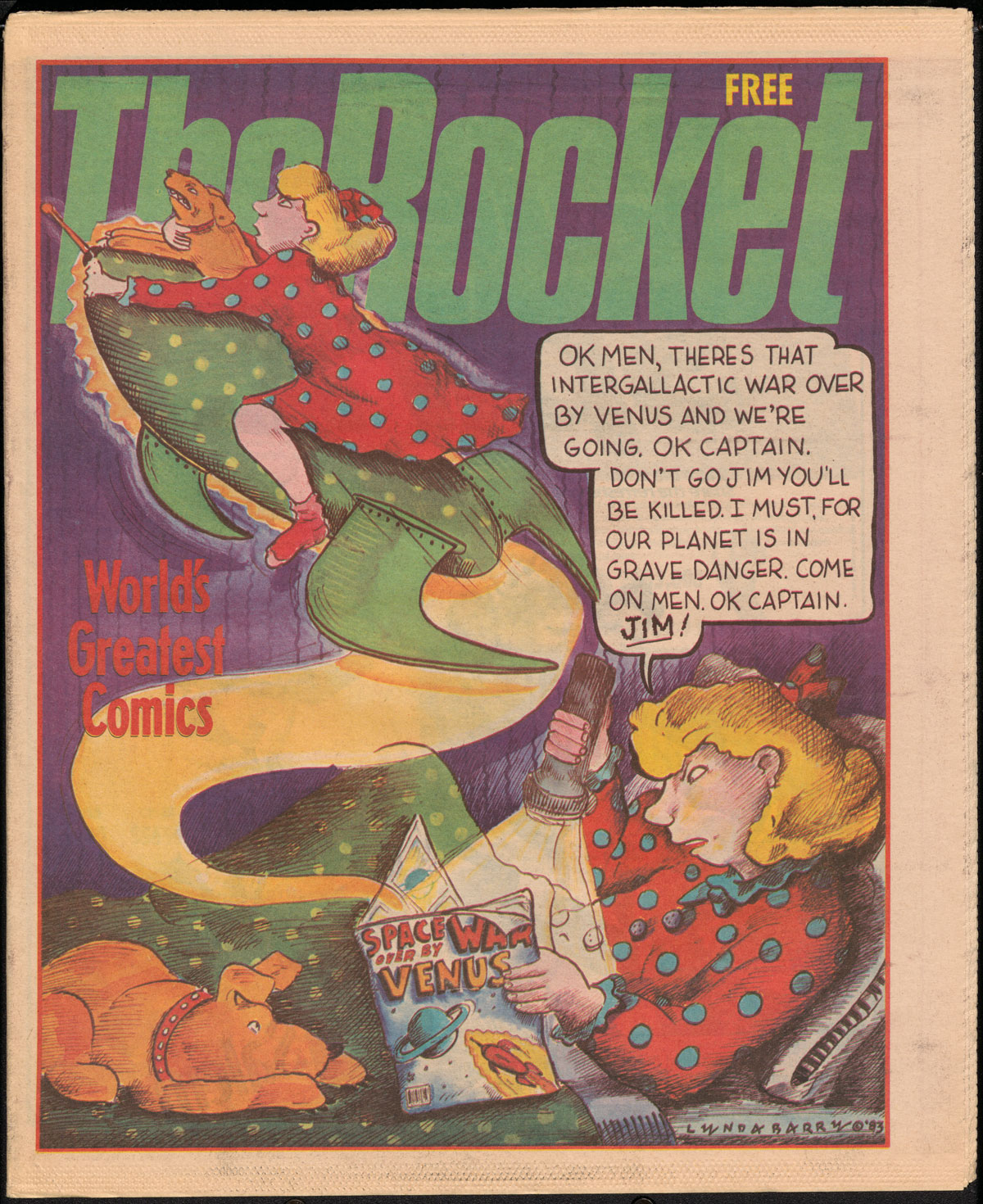

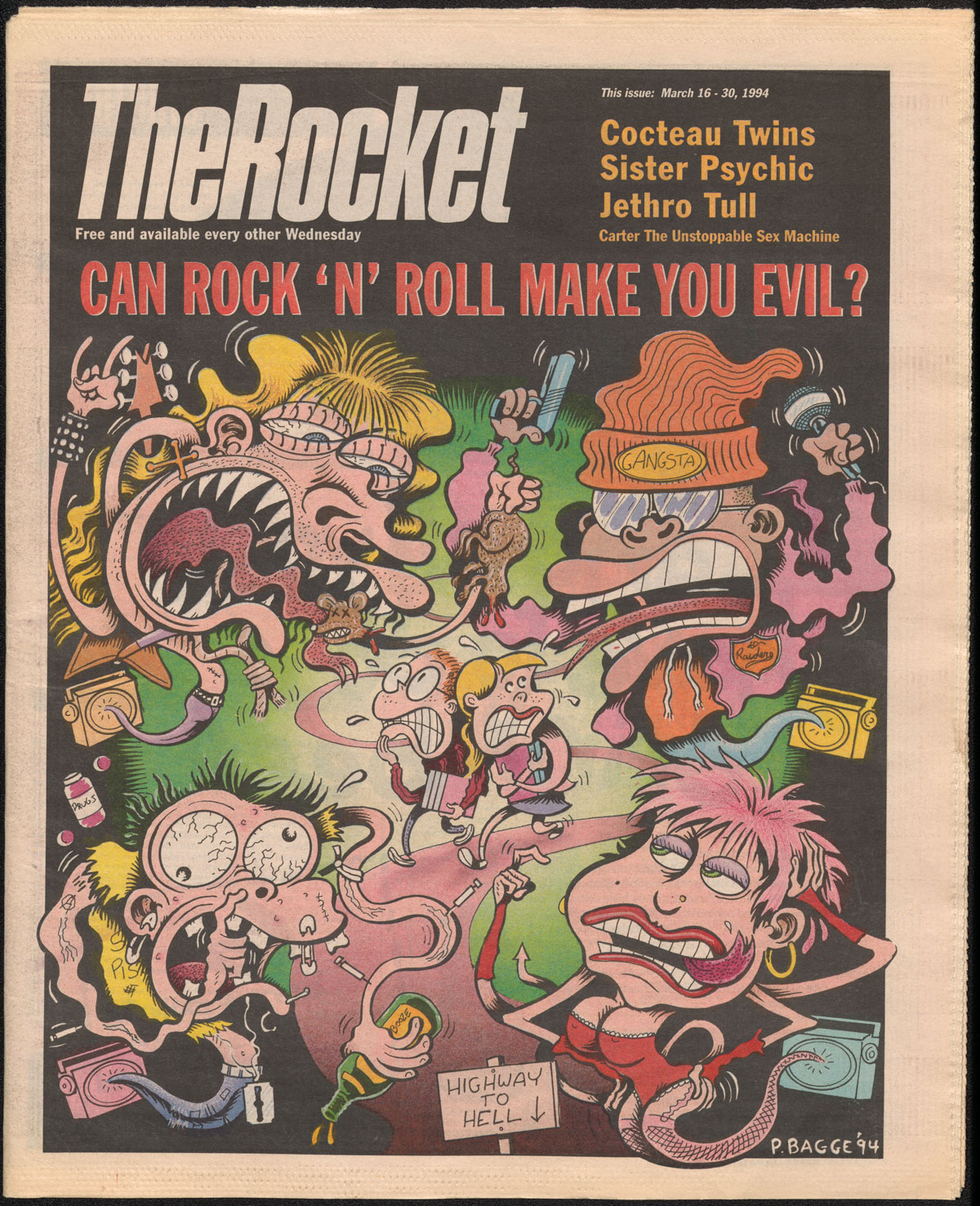

The project to create a database of The Rocket took several years. Ultimately, and maybe fittingly, it was done on old technology—microfilm. All 336 of the issues were recorded and made available to the public through the Washington State Library early this spring. But the project isn’t complete. “We really value the covers,” Albano says—and there are more than 300 of them. So now the UW’s preservation unit is scanning them one by one. “It is a time sink,” Albano admits. But with the great photography, “grungy” design and early-work cartoons from artists including Matt Groening and Lynda Barry, “it’s kind of fun.”

Grunge is having a new moment. Mudhoney guitarist Steve Turner released his memoir, “Mud Ride: A Messy Trip Through the Grunge Explosion,” last summer. The photo-rich book “Charles Peterson’s Nirvana,” was published by Minor Matters Press in March. Tacoma Art Museum and Minor Matters will feature Peterson’s photography (along with work by UW professor emeritus Paul Berger) at an exhibit of the same name in October. And now a there’s new KEXP-produced podcast titled “The Cobain 50.”

Peterson, who will be showing some of his Nirvana photographs at the Tacoma Art Museum this fall, says lately he has been selling masses of art prints from his ’80s and ’90s photos. “It is the 30th anniversary of Kurt’s death [Cobain died April 5, 1994]. That might have something to do with it,” Peterson says. “But young people all along have kind of been looking back at that time. It really was one of the last great movements in rock ’n’ roll.”

Meanwhile, Vallier just finished teaching a spring-quarter course in the UW’s Comparative History of Ideas program titled “Grunge Is for Lo$ers: Seattle’s Alternative Music Scenes, 1964-2024.” “I offered a deep dive into the history and current state of Seattle’s so-called alternative music scenes. We started with the distorted R&B organ stylings of the Dave Lewis Trio and merged into the proto-punk garage rock of Tacoma’s The Sonics,” he says. The course built up to the grunge movement and explored Seattle’s role in the music industry.

“This sounds like a great class,” says Cross. Something profound, something magical happened here in the Pacific Northwest: It is something worth studying, he says.

“We were one of the last authentic cities to create a culture in a pre-internet era,” he adds. “The internet ruined everything. The Seattle music scene only developed because no one outside was paying any attention to it.”