Leisure is not a luxury Leisure is not a luxury Leisure is not a luxury

What if time for leisure isn’t the reward for a good life—but the foundation of one?

By Shin Yu Pai | Illustrations by David Lasky | December 2025

Ours is a culture that glorifies the hustle and grind, with rest becoming a radical act. Americans are working longer hours, taking fewer vacations and reporting record levels of burnout. More than half of America’s workers don’t use all their vacation days even as reports of stress-related illness climb. Productivity is treated like a moral virtue, and unstructured time can feel like a personal failure. But in the race to keep up, experts are starting to ask a different question: What if leisure time isn’t the reward for a life well-lived—but the foundation of one?

Whether you call it leisure, play, self-care, recreation or down time, American culture invests a lot of time defining and judging what we do with our time when we’re not working. Recent articles from The Atlantic, Psychology Today and the BBC question whether there’s such a thing as too much leisure. Even the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics tracks and measures how workers spend their free time, categorizing it into activities like watching TV, socializing or having active pursuits like exercise or playing sports. This fixation with measuring and managing leisure often misses the point: in our efforts to optimize every moment, we’ve become disconnected from the restorative power of simply doing less.

Tiffany Dufu

About 10 years ago, Tiffany Dufu, ’97, ’99, got a wake-up call. In an annual performance review, her boss said, quite plainly, that she needed to get more sleep.

At first, Dufu, a hard-working Gen Xer serving as her employer’s chief leadership officer, dismissed the comment. It didn’t fit with her drive for growth and development. But then her curiosity led her to conduct an experiment. For eight weeks, Dufu committed to eight hours of rest each night and went to bed earlier. It was a revelation, she says: “I discovered that I’d been exhausted for 10 years and didn’t know it.”

That discovery led to her writing “Drop the Ball: Achieving More by Doing Less,” and becoming a sought-after speaker challenging the idea that women need to “do it all.” Today, Dufu supports the economic empowerment of women as president of the Tory Burch Foundation, where she serves as a mentor to women in leadership.

Living in New York City with her husband and two children, she has learned to shrink her to-do list to develop a deeper and healthier relationship with leisure time. The idea of leisure can’t be separated from wellness and rest, she says. “As a Black woman and mother, I have clarity about the demands on who I am psychologically, emotionally, intellectually and physically. Leisure is when I rejuvenate and repair what the world has extracted from me as a resource.”

This recuperative and intentional act of leisure is expanded upon by activists like adrienne maree brown, who frames leisure as a fundamental right and a form of resistance against systems that demand constant productivity, and Tricia Hersey of The Nap Ministry, where rest and leisure are issues of social justice. They advocate for taking time to daydream, detox from digital inputs and read for pleasure.

Amelia Bachleda

As director of outreach and education at the University of Washington’s Institute for Learning & Brain Sciences, Amelia Bachleda, ’08, works with a team that studies the role of unstructured play in human learning and early brain development. “It has an important role in children’s development—it’s how young kids learn and make sense of the world,” Bachleda says. “They need time each day for independent play in order to explore and be part of their own world.”

Unstructured time allows both adults and children to get in touch with their curiosity and creativity. “Play is very motivating for children,” Bachleda says. “It’s how they probe at the edge of their developing abilities.” Unstructured time exists as a space that allows intelligence to wander and can help quiet the mind to feel who we are on the inside, without all the other noise. Though Bachleda takes a generous view when it comes to the value of play and leisure in human development, she acknowledges that different cultures have different ideas of leisure. “Sometimes, it comes with baggage, or guilt,” she says.

“Leisure is when I rejuvenate and repair what the world has extracted from me as a resource.”

Tiffany Dufu, '97, '99

While American culture, sometimes described as “hustle culture,” has perhaps a less-healthy take on productivity over wellbeing, different world cultures reflect varied ideas about leisure and its benefits. The Spanish siesta, Chinese wujiao and Swedish fika are all leisure practices built into the workday. And some societies build generous leave policies into their workplace norms, while others structure four-day workweeks.

Instead of judging oneself by a culture’s predominant values around leisure time, Bachleda asks whether Americans think leisure gets in the way of living a good life, however that may be defined. “We live in the world where there are things we have to do—there are realities,” she says. “We have to make sure we’re safe and cared for to the best of our abilities, and that our bodies and minds are feeling good. Part of that is making time for leisure, which is restorative.”

But there are times when free time isn’t healthy. For residents in a skilled nursing facility with low mobility or dementia, unprogrammed time might lead to boredom, anxiety or feelings of aimlessness—similar to how many people experienced unstructured time during COVID-19.

Daniel Winterbottom

Professor Daniel Winterbottom, a landscape architect, questions whether unstructured time should be defined in the same way as leisure time. Winterbottom designs healing gardens and children’s playgrounds around the idea of “soft fascination.” He creates spaces of rest and discovery that allow the mind to recover and resume its ability to refocus intensively. A person’s cognitive ability declines after six hours. But soft fascination allows the brain to rest and wander. Resetting attention in a garden full of bees and flowers restores a person’s ability for “hard fascination” and extreme focus.

Winterbottom also leads design-build study-abroad trips for students. He has seen his younger co-travelers default to watching movies or scrolling on the internet during downtime in a foreign country. “They aren’t doing something that someone else wants them to do, and they interpret that as part of freedom,” Winterbottom says. “But in my day, leisure felt like it was about exploring things beyond the classroom and building on one’s curiosity with the physical world. I’m struck that they have a totally different idea [of leisure] that often is devoid of ‘real’ nature and direct human interaction.”

Dufu, who wrote “Drop the Ball” in 2017, says that the American idea of leisure can suggest idleness, which sits alongside laziness. It’s important to distinguish how an individual thinks about free time, or time that is not already devoted, scheduled or committed to doing other things, she says. “Leisure looks very different to different people, because every human being has different motivations. Self-awareness is key to aligning a person’s free time with satisfaction. If you understand yourself, you understand what motivates you and can be strategic about the free time that you have.”

While it might feel counterintuitive to plan leisure, the more demands a person has upon their time, the more important it becomes to carve out that space. For those looking to reorient their relationship to leisure toward fulfillment, Dufu suggests a few exercises: Go back to a moment when you were a child and didn’t yet have school or chores. How did you spend your time? Dufu spent a lot of her unstructured time as a child imagining and exploring. This is expressed in how she uses her leisure time today, seeking out activities that feed her curiosity. But another child might have loved moving their body by playing sports in the streets. Try turning back to a time before responsibility to recover what you loved doing, Dufu says.

While it might feel counterintuitive to plan leisure, the more demands a person has upon their time, the more important it becomes to carve out that space. For those looking to reorient their relationship to leisure toward fulfillment, Dufu suggests a few exercises: Go back to a moment when you were a child and didn’t yet have school or chores. How did you spend your time? Dufu spent a lot of her unstructured time as a child imagining and exploring. This is expressed in how she uses her leisure time today, seeking out activities that feed her curiosity. But another child might have loved moving their body by playing sports in the streets. Try turning back to a time before responsibility to recover what you loved doing, Dufu says.

She also suggests engaging others as you reclaim your relationship with leisure. Ask eight to 12 people to identify a time when they’ve seen you at ease and at your best. What were you doing and what did that look like? Invite them to reflect their positive perceptions of you. Then listen and see if you recognize any patterns.

On a more practical level, researchers like social psychologist Cassie Holmes suggest carving out two hours for leisure a day, the minimum amount that time-poor individuals need to feel less stressed. Leisure doesn’t need to occur all at once. It can be made up of short walks, coffee breaks, reading a book chapter or just discretionary time doing what you want. It all adds up. Like practicing an instrument for 10 minutes here or carving out time on the meditation cushion there, you slowly build the muscle that allows sinking into the space of leisure that matters most.

On a more practical level, researchers like social psychologist Cassie Holmes suggest carving out two hours for leisure a day, the minimum amount that time-poor individuals need to feel less stressed. Leisure doesn’t need to occur all at once. It can be made up of short walks, coffee breaks, reading a book chapter or just discretionary time doing what you want. It all adds up. Like practicing an instrument for 10 minutes here or carving out time on the meditation cushion there, you slowly build the muscle that allows sinking into the space of leisure that matters most.

No matter where your reflections point you, experts emphasize embracing your own personal ideas of leisure and refraining from judgment. Leisure time is never time wasted. “I see lots of headlines and pressure to do leisure well,” Dufu says. “There’s a lot of defining of what leisure and free time can be. But you can make it whatever you want. If your idea of leisure time is climbing Mount Everest, then just accept that. If you’d rather watch ‘Real Housewives’ while eating potato chips, go for it! Some people want to take their brain somewhere else. They need that. My husband loves watching sports. But if I have an hour, I’m not going to watch Formula One, I’m going to come out of that time feeling like I’ve stretched myself.”

During the pandemic, Winterbottom took up urban sketching—an activity that encompasses wandering, exploration, visual notetaking and hiking. Sketching in his journal puts Winterbottom in a mindset of complete immersion, a flow of “natural systems that go into a different rhythm.”

During the pandemic, Winterbottom took up urban sketching—an activity that encompasses wandering, exploration, visual notetaking and hiking. Sketching in his journal puts Winterbottom in a mindset of complete immersion, a flow of “natural systems that go into a different rhythm.”

“There’s a difference between leisure and aimlessness,” he says. “Leisure can open doors to new perspectives and experiences.”

In the end, leisure isn’t something to earn—it’s something to reclaim. Whether it’s two hours a day or 10 stolen minutes, time spent in rest, curiosity or play is not wasted. It’s invested in the renewal of your energies. As Dufu reminds us, leisure can take many forms, from daydreaming to watching TV, sketching in a journal or simply doing nothing at all. What matters is that it feels restorative.

So avoid measuring your free time against how it looks to others. Ask instead: What kind of leisure actually restores me? What makes me feel good? The answer might not be obvious at first, but it’s worth pursuing. The right amount of leisure might be exactly as much as you can fit in.

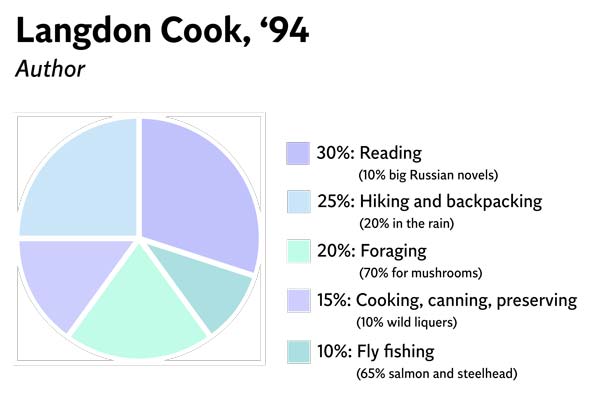

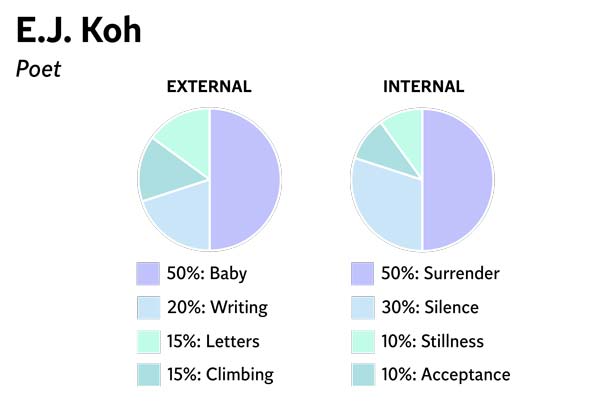

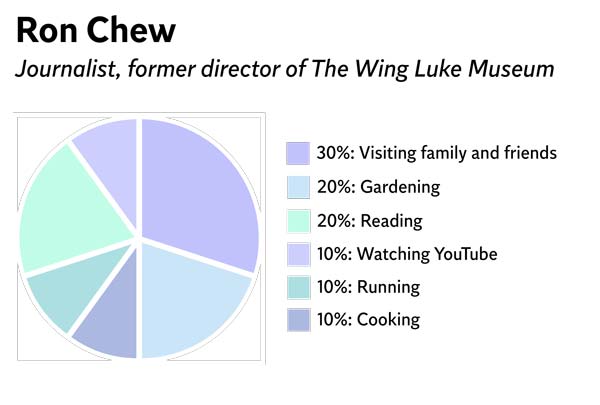

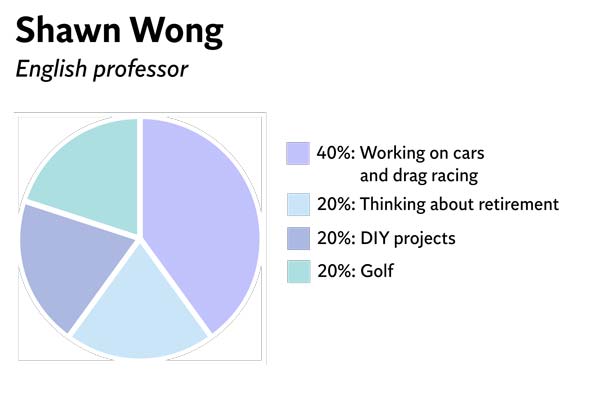

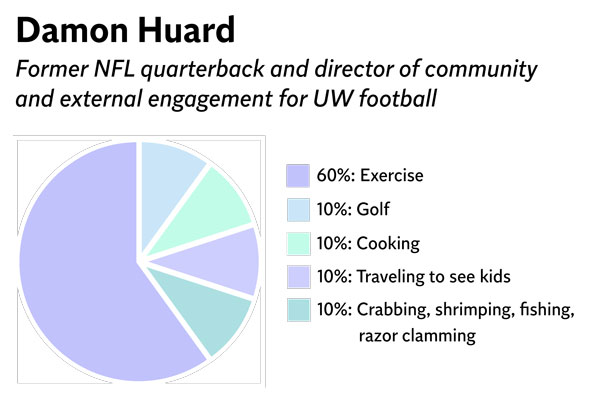

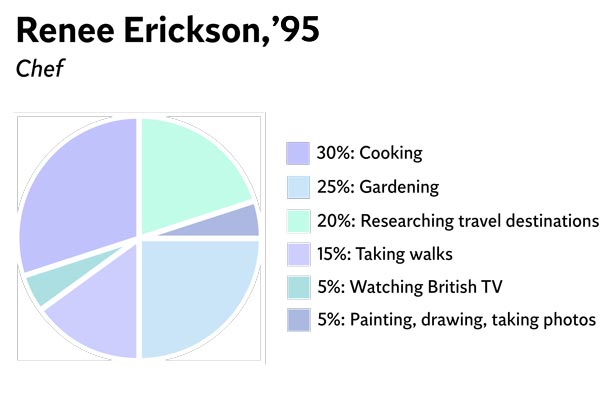

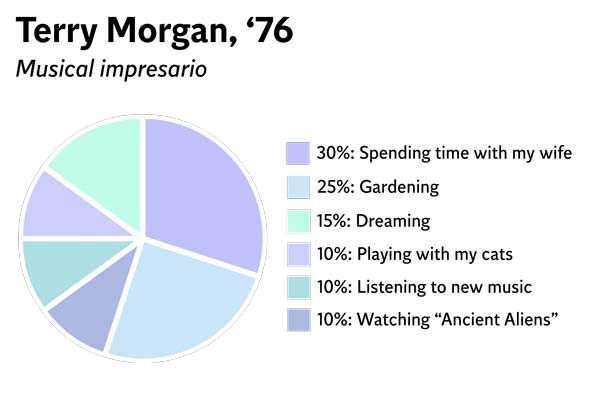

What’s your leisure?

We asked UW alumni and friends of UW Magazine to tell us how they fill their leisure time. Here’s how they responded.

Click the pie charts for a larger image.