Lifesaving ideas Lifesaving ideas Lifesaving ideas

Dr. Leonard Cobb’s innovative ideas, collaboration and focus on improvement created two of the most important lifesaving initiatives of our time.

Dr. Leonard Cobb’s innovative ideas, collaboration and focus on improvement created two of the most important lifesaving initiatives of our time.

It’s a typical weekday in downtown Seattle when a siren screams to life, piercing the air and bouncing off the high-rises. Cars scoot out of the way so the red Medic One ambulance can hustle to the scene of the emergency. There, on the sidewalk, a man has crumpled to the ground in pain and short of breath. He’s been felled by a cardiac event of some sort.

The reality is this individual’s health catastrophe could not have happened in a better place, for Seattle is among the top-performing programs in the world for saving the lives of cardiac arrest victims and critically ill patients outside of the hospital.

Much of the credit goes to Leonard Cobb, who in the 1960s was chief of cardiology at Harborview Medical Center and a professor of medicine at the UW School of Medicine. Cobb was impressed by the work being done in Belfast, Northern Ireland, that increased the chances of survival of patients suffering cardiac events outside of a hospital. That program employed what was called a mobile coronary care unit, staffed by a resident from a Belfast hospital, and it would travel to the homes of patients who appeared to suffer from a myocardial infarction, a condition also known as a heart attack. “That,” Cobb said in a 2020 interview, “was the first attempt where organized medical care was provided outside the hospital on a regular basis.”

That epiphany inspired Cobb to collaborate with Seattle Fire Chief Gordon Vickery to create of one of the biggest lifesaving initiatives the U.S. has ever seen: Seattle’s renowned Medic One paramedic program. Cobb, the ultimate lifesaver, died Feb. 14 at the age of 96. But his legacy—a model for emergency care everywhere—continues to touch lives from coast to coast.

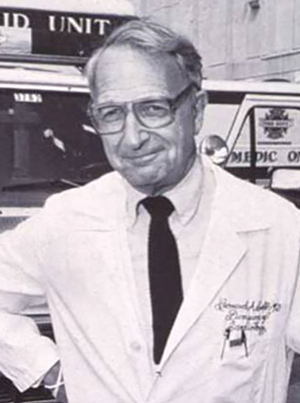

Leonard Cobb helped create Seattle’s Medic One program.

“Dr. Cobb envisioned a team of clinicians providing expert care—comparable to or better than what happens in the hospital,” says Dr. Tom Rea, medical director of King County Medic One and a UW professor of general internal medicine. “He was a pioneer by being one of the first persons to create this new field of medicine—pre-hospital emergency care. He developed a response system by partnering with public service (fire department) and helped create a new type of provider”: the paramedic. That led to the development of the UW’s Paramedic Training Program.

Cobb’s innovation and impact has been nothing short of astonishing. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than 800,000 people suffer a heart attack every year. And that’s not taking into account that there are many types of heart emergencies. In addition to heart attacks, which are caused by serious blockages in a patient’s heart vessels that require emergency treatment, even more time-sensitive is cardiac arrest: when a person’s heart completely stops beating and the patient loses consciousness and becomes lifeless.

Beyond Cobb’s innovative idea to train paramedics in CPR and other lifesaving skills was perhaps an even more important accomplishment: teaching community members how to do CPR. “When someone suddenly collapses, people nearby need to call 911 and start hands-only CPR,” says Dr. Michael Sayre, medical director of Seattle Medic One and a UW professor of emergency medicine. “Dr. Cobb helped create a program in Seattle to train anyone to do CPR. That program helped influence major national organizations that CPR could be done by anyone, not just nurses, doctors, firefighters, or paramedics.” In 1971, Cobb, Vickery and Seattle Rotary No. 4 launched Seattle Medic Two to train community members in CPR. “This was perhaps our most important contribution,” Cobb said. To date, the Seattle Fire Department’s Medic Two program has trained more than 1 million people in CPR.

“Dr. Cobb understood that there are emergency conditions like heart attack, stroke, major trauma that are time-sensitive and that earlier treatment can be the difference between life and death,” Rea adds. “Before Medic One, patients were often on their own to navigate to the hospital. Consequently, some patients died before they arrived at the hospital or arrived in moribund condition, having lost opportunities for critical, time-sensitive treatment.”

“He made you want to try harder. He was genuinely interested in your perspective. As a consequence, he was influential and got things done.”

Tom Rea, King County Medic One medical director

Cobb’s success was also due to his focus on evaluating and measuring results so they could be improved upon. “His insight and wisdom were highlighted by how much value he put on measurement in order to understand process and ultimately improve care and outcomes. He was truly a pioneer of quality improvement and health services research,” says Rea, who knew Cobb for more than 25 years and worked with him during his residency three decades ago. “He had an engaging smile and a good nature. He always had the ability to challenge and encourage you simultaneously. … He made you want to try harder. He was genuinely interested in your perspective. As a consequence, he was influential and got things done.”

After the grant for the program was cut, Cobb and Vickery, the Seattle fire chief, began a grassroots fundraising campaign that raised almost $200,000. That campaign led to the formation of the Medic One Foundation, which continues to support the direct costs of training Medic One paramedics in Seattle, King County and surrounding communities.

Cobb wasn’t through yet. In 1984, he successfully advocated for emergency medical technicians to use automatic external defibrillators (AEDs). And in 2008, he helped create the Resuscitation Academy, a regional organization dedicated to helping communities develop and implement emergency medical plans to improve CPR. He served as president of the Medic One Foundation for 30 years and was on its board up until his death.

“I am so grateful to have known Dr. Cobb,” says Heather Kelley, a Medic One Foundation board member who collapsed from sudden cardiac arrest in 2014. Her two daughters called 911 and began CPR. Paramedics had to shock Heather’s heart three times before getting a heartbeat. “My near-death experience deepened my sense of gratitude to Dr. Cobb and the Medic One system. Because of them, I’m able to continue being a mom to my beautiful and brave daughters.”