The shootaround was over, and the Husky basketball team had showered, changed and was off to relax before a big game against perennial national powerhouse UCLA that night at Hec Edmundson Pavilion. But walking past the practice gym a while later, Husky player Stan Walker, ’80, could have sworn he heard something going on inside.

Funny, he thought. The gym was supposed to be empty. Then he looked inside—and shook his head.

“Lorenzo,” he yelled, “what are you doing? We have a game tonight! If coach finds you, he’ll kill you. You are supposed to be resting.”

Lorenzo Romar, the star point guard of that 1979-80 University of Washington basketball team, was indeed inside the gym, all by himself. Shooting jump shots. Working on his moves. Practicing layups. Yes, he was the first player at practice that day, as always. And he was the last to leave. As always. Typical Romar; he just couldn’t get enough. He was always dropping into the IMA for pickup games in between classes, on weekends, in the evenings. During basketball season, it seemed like he was always on the court.

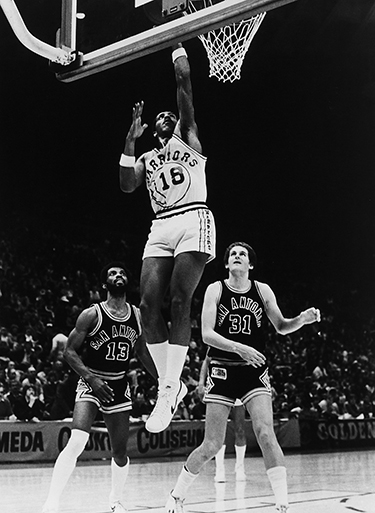

Lorenzo Romar during his playing days.

You can find the affable, dedicated-to-a-fault Romar back on the UW campus these days, but not to play. He’s back as the new UW men’s basketball coach, charged with turning around a program that plummeted to the ranks of the has-beens of the Pac-10 after tasting national success as recent as five years ago.

The story line couldn’t be sweeter—former UW basketball star comes back to coach at his alma mater (although he didn’t graduate—he finished his degree a decade later at the University of Cincinnati). His credentials are impeccable-star player at the UW for two years, a five-year NBA career, seven years playing and coaching with Athletes in Action, followed by an even more eye-opening coaching career. He was an assistant at UCLA from 1992-96, and recruited many of the stars on the Bruin team that won the 1995 national championship. Then he had head coaching stints at Pepperdine (1996-99) and St. Louis University (1999-2001), where he righted two struggling programs.

Here, he takes over a program that under former coach Bob Bender lost 58 games the past three seasons, saw team chemistry become a cruel joke and watched players’ academic work deteriorate. Moreover, UW players like Dan Dickau (a recent NBA first-round draft choice) and Senque Carey transferred to other schools while top local high school players like Curtis Borchardt and Jason Terry spurned the UW to go out of state.

“If anyone can turn around Washington, it’s Lorenzo,” says Jim Harrick, the head coach at the University of Georgia and the man who hired Romar as an assistant at UCLA in the early 1990s. “He is the classic underdog who succeeded all the way.”

Perhaps the only thing bigger than Romar’s passion for sports—basketball in particular—is the list of obstacles he has overcome in landing what he called his dream job.

Money was tight when he and his younger brother grew up in Compton, Calif., a lower-middle class suburb a few minutes south of Los Angeles. Their father, a welder, and their mom, a manufacturing plant supervisor, sacrificed to make sure their sons could attend Catholic school. “My parents worked all the time,” Romar, 43, recalls. “They never, ever missed a day. We grew up in the inner city, we had food on the table, a place to stay. We had the basics.”

Heading north

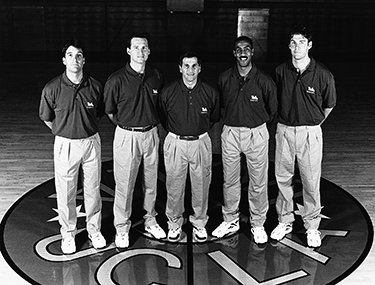

Lorenzo with the coaching staff at UCLA.

A sports nut ever since he can remember, Romar always loved basketball most of all. But for years, his dreams far exceeded his reach. He was cut from his high school team as a 5-foot-6 sophomore and a junior but made the team as a senior—only to be benched after the season opener. Frustrated at his benching, he talked back to his coach and was suspended from the team. With no colleges interested in an undersized, inexperienced guard with an attitude, he decided to try out at Compton Junior College, just blocks from his home. The coach politely told him to get lost.

His dreams of playing college and pro ball seemed at a dead end. He wasn’t ready to give up, though, and went to try out at nearby Cerritos Junior College. His freshman year wasn’t anything special, but as a sophomore, he averaged 14.1 points a game, set a school record for single-season assists, and earned first-team all-league honors. Cerritos (23-8) made the state tournament, where Romar played spectacularly. Many people noticed—including Marv Harshman.

Harshman, then the UW coach, had come to Los Angeles to scout a highly touted guard in the tournament’s 9 p.m. game. But after seeing Romar in the early evening game, he wanted him instead. A visit to Seattle—which included a cruise on Lake Washington—won Romar over in a second. (So did the purple Converse sneakers Harshman sent Romar—that was legal back then.)

Overcome with excitement, Romar and a friend drove 21 straight hours from Southern California to Seattle. Upon wheeling into campus, Romar poked his head in the IMA, saw a game in progress, dashed back to the car, got his stuff, and went to play—for four solid hours.

A swift, 6-foot-1 point guard with a cool head, Romar made an immediate impact on the Husky team. “You could tell he was a great player, but more than that was the way he treated us,” recalls teammate Steve Matzen, ‘80. “He had a great ability to communicate with everyone on the team. He made you feel a part of everything—even when he poked fun at you.”

Romar played two years with the Huskies, going 11-16 and 18-10. The team captain as a senior, he was twice voted most inspirational player by his teammates. One reason was his knack of playing great against the best opponents. For instance, in a 72-70 upset of UCLA at Pauley Pavilion in 1980, Romar went 6 for 6 from the floor, 6 for 6 from the free-throw line, had four assists and no turnovers. “He played a perfect game,” former teammate Stan Walker recalls.

“You could tell he was a great player, but more than that was the way he treated us. He had a great ability to communicate with everyone on the team.”

Steve Matzen, ‘80

But Romar admittedly had one downside—he was a far better student of the game than in the classroom. “I wasn’t serious about my studies,” Romar admits. “Basketball was everything to me. I was the first person in my family to go to college, but I didn’t take my schoolwork seriously.” By the end of his senior year, he did not have enough credits to graduate, and his NBA dreams were thought to be pure fantasy. After all, the NBA doesn’t take too many 6-foot-1 guards who don’t score a whole lot (he averaged 9.3 points as a UW senior).

The Golden State Warriors took a flyer on him, grabbing him in the seventh round of the 1980 NBA draft. (Romar learned about it while shooting baskets in the IMA, of course), giving him a microscopic chance.

When he showed up at camp as an anonymous rookie competing for a job against stars like Bernard King and NBA scoring leader World B. Free, Romar was awed. “I saw all these big players and I thought they were the forwards,” he recalls. “I couldn’t believe it when they told the guards to get in one line, and they all joined me.”

“Every night after practice, he was my first cut,” recalls Al Attles, then the Warrior coach and now a Warrior vice president. “I don’t mean to sound harsh, but he was just practice fodder. He had no chance. But every night, I would think, Gee, he actually did something nice in practice today, let’s keep him one more day.”

What made the impression on Attles? “I made sure to stay after practice, even the two-a-days,” Romar says. “I would do a few dunks to show them, ‘Hey, I am not tired. I am excited to be here.’ ” Sound familiar?

‘People are just drawn to him’

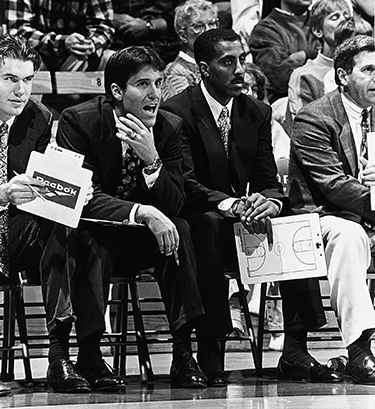

Lorenzo Romar on the bench at UCLA.

Thus, the inexhaustible Romar carved out a pro career that lasted five years with three teams. He left the NBA to play for Athletes in Action, the athletic division of Campus Crusade for Christ, a non-denominational ministry. While in his mid-20s, he decided to take religion seriously, and credits it with changing his life. For example, while living in Cincinnati, where Athletes in Action was based, he decided to go back to school to finish his bachelor’s degree in criminal justice at the University of Cincinnati. (Athletes in Action plays exhibition games against college teams, followed by ministry to those in attendance. The organization also develops and runs ministry-based social services in various communities.) Romar’s play was stellar, and he was growing a reputation as a solid coach. In 1992, UCLA’s Harrick called to ask him to join his staff as an assistant coach.

At first, Romar wasn’t sure if he wanted to go into college basketball, especially a pressure cooker like UCLA. He loved playing for AIA and running his inner-city ministry, where he helped underprivileged kids get tutoring and other social needs filled. But in the end, he couldn’t turn down a chance to work at a basketball school he idolized growing up. (As a teen-ager, he took the bus from Compton to the UCLA campus to catch a glimpse of pro players who worked out at the UCLA gym.)

Romar had an immediate impact there. As an assistant coach, he recruited many of the players on the 1995 team that went 31-2 and won the national title when the Final Four was held in the Kingdome.

“His strength is in the relationships he forms,” says Cameron Dollar, a player on that ‘95 UCLA team and now Romar’s top assistant. “He had this way of making you want to do right by him. As a player, you never wanted to let him down.”

Adds Jelani McCoy, another member of the ’95 UCLA team who now plays for the world champion Los Angeles Lakers: “Coach Romar tries to get the maximum out of his players. If he had told me to run through a brick wall because it would have made me a better player, I would have done it.”

“He wants to see things through. He’s a builder. He likes to build relationships with everyone from the star player to the janitor.”

Steve Lavin, UCLA coach

“He’s as dynamic a personality as you will find,” adds current UCLA coach Steve Lavin, who served as a Bruin assistant with Romar and is one of his closest friends. “He has great charisma and character—and the ability to inspire and motivate people. People are just drawn to him.

“He wants to see things through. He’s a builder. He likes to build relationships with everyone from the star player to the janitor.”

The fun-loving Romar (he does killer impressions of basketball coaches and players) takes his relationships very seriously. That’s why it was so hard for him to leave UCLA after the 1996 season for his first head coaching opportunity at Pepperdine. With the Waves from 1996-99, he became a beloved figure, engineering a dramatic turnaround after a 6-21 inaugural season, going 17-10 and 19-13 with an NIT berth by his third season. The future looked even brighter, but he couldn’t turn down a golden opportunity to take over at Saint Louis University. In the spring of 1999, when he assembled his Pepperdine players to say goodbye, he broke down in tears several times.

The Southern California native took to the Midwest in no time. Romar led Saint Louis to a 51-44 record and an NCAA Tournament berth in three seasons. Just like at Pepperdine, he set up the Saint Louis program for even more glory, with all starters returning for the 2002 season, when the phone rang. UW Athletic Director Barbara Hedges was on the line to talk about the Husky job.

Despite his impressive credentials, Romar was not Hedges’ top choice to replace Bender. She reportedly talked to Missouri’s Quin Snyder, Gonzaga’s Mark Few and Minnesota’s Dan Monson before she turned to Romar and named him the UW’s first African-American basketball coach (not to mention its highest paid hoops coach at $700,000 a year).

“Lorenzo Romar is a terrific fit for the University of Washington,” Hedges said. “He played here, he knows the Pac-10, and more importantly, he has the character and leadership to lead the program.”

The secret to success

Romar and the UCLA staff celebrate a victory.

The secret to Romar’s success is simple: Discipline. Respect. Accountability. He treats his players as he does his wife Leona (whom he met in high school) and his daughters Terra, Tavia and Taylor. “X’s and O’s mean nothing if players don’t respect the coach or each other,” he says.

Once again, the impact he has made on his Husky players has opened eyes. “He’s upbeat, laid back, but confident,” says junior guard C.J. Massengale. “He’s calm and respectful. Discipline is very big with him. And we need it.”

One player who learned quickly about that was guard Will Conroy, who showed up two minutes late to the players’ very first meeting with their new coach. Romar interrupted the meeting to tell Conroy to leave the room. “He won’t raise his voice, he won’t embarrass you, but he gets his points across,” Conroy says.

“We know we have the talent to do better than we have. It’s really a matter of team chemistry. Coach Romar knows what it takes to get there, and we are listening.”

Romar explains: “Winning games is not my only job. I need to build character and be a positive influence on the players’ lives. I’m in this to nurture players so there can be a trust. They have to know I’m here for them. I don’t believe you can’t be someone’s friend and their mentor, too.”

By emphasizing discipline, Romar isn’t saying he will come down hard on someone who breaks a rule. “Discipline simply is doing what you should at the right time,” he explains.

“As a coach, you can’t always be sure. If a player takes a bad shot, do I get on him for taking the bad shot? Maybe he will clam up and not say much, or not want to take a chance again. You have to find the right balance.”

His approach has impressed everyone he has come across. “He has the type of moral character that we need in basketball today,” says John Wooden, the legendary UCLA basketball coach.

As was the case everywhere else he has been, Romar had an immediate impact at the UW. He convinced forward Doug Wrenn, the UW’s best player, to return for his junior season instead of applying for the NBA draft. He scored a recruiting coup, signing Bobby Jones, a talented 6-foot-7 forward from Long Beach Poly High School in California. He went down to the wire against UCLA with highly touted high school center Ryan Hollins before losing the Los Angeles native to the Bruins.

While he plans to recruit players from California, his primary goal is to get the city’s and state’s best players to come to the UW. “It will take a while, but we are going to establish the Washington program as a contender,” Romar says.

On Washington being a football school, Romar isn’t fazed in the least. “I think it is a great combination that we have both football and basketball. It is not an insult to be here at Washington. I don’t think there is any question with the commitment and resources we have that we can be successful here at Washington.

“I have been told many times, especially in NBA camps, ‘You can’t do this,’ so that doesn’t really faze me. We can do it. I know it.”