In the winter garden of the American Express building in downtown Minneapolis, the hardwood floor dips and rises like a gently rolling landscape. Maya Lin, who designed the space, is an artist who gets "fixated on things," she says, and one of her longtime fixations was the idea of an indoor hill. But because it's a permanent artwork, and must therefore be wheelchair-accessible, its contours aren't as severe as Lin would've liked.

Maya Lin

“As I walked on it for the first time,” she says, “all I could think was, wow, I’d really like to push this—to make this curve, this hill, something extremely tall, so it could actually get you to a different relationship to the ceiling.”

When Lin returned to her studio, she pushed it, and the result is 2X4 Landscape—an imposing hill made of thousands of upright two-by-fours that’s currently being assembled in a warehouse in South Lake Union. In mid-April it will move to the Henry Art Gallery, becoming one of three large-scale installations in Lin’s first major museum exhibition since 1998.

“Maya Lin: Systematic Landscapes” is a big-time show by a bigtime artist— someone who knows, as the grim joke goes, what the first sentence of her obituary will say. In 1981, while an undergraduate at Yale, Lin won a national competition to design the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. Her entry—a chevron-shaped wall of black granite inscribed with the names of more than 58,000 American servicemen and women killed in Vietnam, which seems to emerge from and disappear into the earth—is now the most visited memorial in the United States.

Lin’s most recognized work is the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. Photo by Terry Adams, courtesy of the National Park Service.

Lin is proud of the wall, but ambivalent about the fame it brought her. She worries about being defined by something she did when she was 21, and has let it be known that she won’t be building any more memorials. “I have fought very, very hard to get past being known as the Monument Maker,” she told Louis Menand of the New Yorker a few years ago. At the same time, much of what she has done outside the monument genre—from houses she has designed to large environmental installations like the new Confluence Project along the Columbia River—is clearly an extension of the work she began with the wall. Lin is obsessed with landscape, and with the ways people experience, inhabit and transform it. She is constantly introducing natural elements into synthetic environments, and vice versa. The difference between a wall coming out of the ground and a hill in the middle of a room is a difference of inflection, not of idiom.

And even her non-monumental work tends to be monumental in scale—grand but ambiguous statements. 2X4 Landscape, for example, requires 2,800 square feet of uninterrupted space. It is composed of nearly 70,000 boards that range in height from a few inches to nine-and-a-half feet. When regarded from some angles, it appears to be a hill. But one of its faces is so steep that in profile it looks like something much more fluid and, potentially, threatening—a cresting wave. Both forms are natural, as is the material, but because the boards are cut to different lengths and the overall surface has not been sanded down, the piece’s texture is decidedly inorganic. It appears to be pixelated.

“Something in the piece is always contradicting itself,” Lin says. “I figured out that if I made it more pixelated, it would seem to be growing and emerging—an inorganic organic process.”

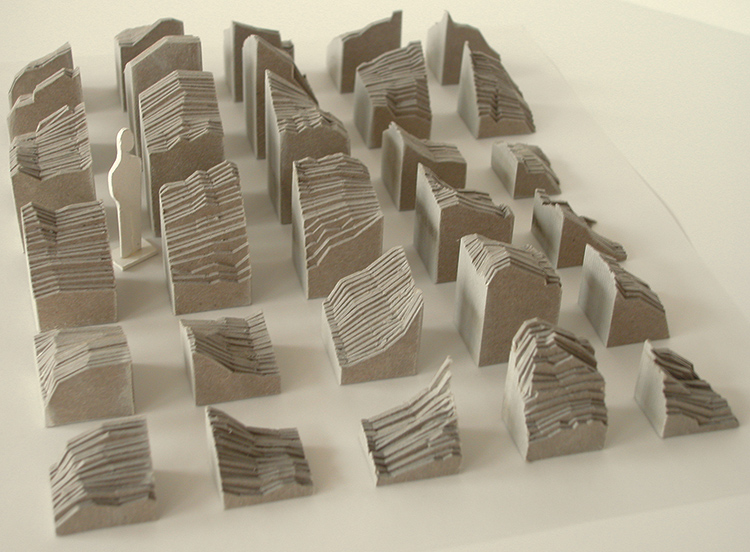

“Landscape” depicts a mountain range sliced into sections. Photo courtesy of Maya Lin Studio.

The Henry, with its viewing balconies, double-high ceilings and large, column-free spaces, is one of only a handful of galleries in the country that can accommodate “Systematic Landscapes,” says Director Richard Andrews. Along with 2X4 Landscape, the exhibition includes a giant, suspended wire-frame replica of an undersea topography that Lin discovered in an atlas, which visitors will be invited to view from both above and below (pictured at top); and a particle-board rendering, in cross-sections, of a mountain range that’s visible from Lin’s summer home in Colorado. Another of her fixations, she says, is what lies beneath the surfaces of familiar things.

It’s a challenging scale at which to make art, because the finished works exist only in her mind until the day they’re installed. Lin tends to keep a close eye on the construction process, making modifications along the way. But she doesn’t worry too much about producing pieces that work in theory and fail in practice, she says. “I really do trust my eye in relation to the models.”

She has good reason to. She may, in fact, be the best living judge of how an artwork that exists only in miniature will play at full size. The resounding success of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial makes it easy to forget what a controversy it created in 1981. Some veterans deeply resented the fact that an artist so young (and so Asian) had won the competition. Virtually every aspect of Lin’s design—its shape, its blackness, its subtlety, and its lack of familiar symbols, such as bronze figures or an American flag—came in for criticism. Editorialists called it “an Orwellian glop,” “an open urinal” and “a black gash of shame.” A loose coalition of pundits and politicians, including Pat Buchanan, Ross Perot and Representative Henry Hyde, demanded that it be scrapped.

From some angles, “2×4 Landscape” appears to be a hill; from others, a wave.

Yet Lin never doubted the rightness of her design—a self-certainty she now attributes to her youth. She knew that people would be moved by the monument. She knew they would cry. She knew they would find it impossible not to touch the carved names. And she knew that only black granite would do.

“I think what caught people unawares,” says Andrews, “was the aspect of the polished stone that reflects the living in the names of the dead. Nobody had caught that in the drawings, or it certainly hadn’t been much talked about. But it was in Maya’s mind. I think there was something about the ultimate shape and form and materials of the work that was stunning, on a national level—as in being stunned.”

“Systematic Landscapes,” Andrews says, is a major show that grew out of a modest proposal. About four years ago, he attended an early briefing on the Confluence Project—Lin’s largest public monument to date. “And I was thinking to myself, ‘Gosh, it would be great to bring some of these models and drawings to Seattle audiences,”‘ he says. After a few conversations with Lin, however, he realized she had something much bigger in mind, and that he, unlike many museum directors, had the space for it.

“2X4 Landscape” requires 2,800 square feet of uninterrupted space. It is composed of nearly 70,000 boards.

Another happy coincidence is that Lin has a personal connection to the UW. It’s where her parents met, and where she spent a small part of her childhood. In the mid-1950s, Julia Chang and Henry Huan Lin were both graduate students at the University and recent refugees from communist China. (Julia had been smuggled out of Shanghai on a junk boat with $20 sewn into the collar of her coat). They fell in love, married and moved to Athens, Ohio, home of the University of Ohio, where Henry had accepted a teaching position in the ceramics department. In 1964, Julia took her two young children back to Seattle for a year to finish her Ph.D.

Maya says she doesn’t remember much about that year, beyond a few impressions—“The graduate student housing at that time was behind the trash dump, and it smelled interesting,” she says. “And I remember seagulls. Millions of seagulls.” Returning to the UW feels more like a homecoming to her mother—whom she plans on bringing to the Henry opening—than it does to her, Lin says. But a past visit to the University did yield the unexpected pleasure of meeting people who still remembered her father.

“My dad passed away in ’89,” she says, “and I completely adored him. To run into people who had been his students or colleagues in the ’50s, to have them come up to me and say, ‘I knew your dad’—that kind of connection has an incredible importance to me.”