Named one of the 10 outstanding governors of the 20th century, Daniel J. Evans, '48, '49, has also served his state as a legislator, U.S. senator and college president.

Along the way, he has always held a special place in his heart for his alma mater—a loyalty that began when he sneaked over the fence during football games in the 1930s. Now stepping down after two terms as a UW regent, Evans reflects on his many UW connections in this interview with Neil McReynolds, ’56, an award-winning newspaper editor, Evans’ former press secretary, and a longtime business and civic leader in the Seattle area.

What was your first involvement with the University?

I grew up close to the University. My first association was going over on a Saturday morning early and climbing a tree that was right next to the fence by the open end of the stadium. And we’d all climb the tree and all at once drop inside and scatter like a bunch of quail while the guys guarding the fence made a half-hearted attempt to get us.

Evans as an ROTC cadet during World War II. Photos courtesy of Dan Evans.

Did you consider any schools other than the University of Washington?

No, I didn’t. When it came time to go to the University, it was during the war. I graduated in February of 1943 from [Seattle’s] Roosevelt High School. At 18 you got drafted. Another fellow who lived on the same street and I signed up for the V-12 program, which was the naval officer training program. My first duty station was the UW. I graduated from Roosevelt on a Friday and started at the University the next Monday.

To many people, it is hard to imagine a person who has been so successful as a politician whose education was engineering. What made you choose engineering?

I was always good at math and science and physics. My father was an engineer, and I admired him very much. He served for 13 years as King County engineer. He was a graduate of the UW Department of Civil Engineering in 1917. And then, when I went into the Navy, there was no choice. You took about half of the hours during your naval training as naval courses and the other half were engineering.

Did you get your start in politics on campus?

No, no, I really didn’t. I only stayed at the University for eight months and then I got transferred to the Naval ROTC program at Berkeley. I received my commission as an ensign in June 1945 and spent the next year on aircraft carriers in the Pacific. I stayed in the Navy until July of 1946. Then I came back and restarted at the UW that fall.

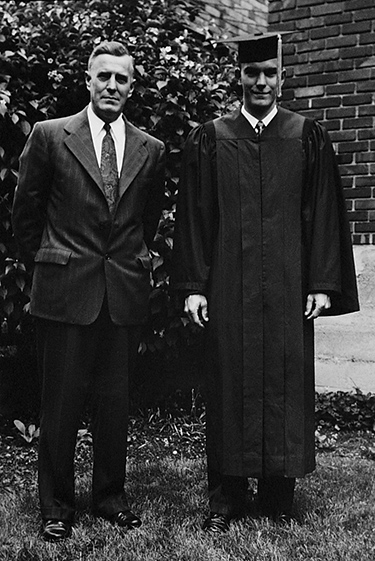

Evans and his dad at the 1948 UW graduation.

So when did you finish up your degree?

I didn’t take very much part in activities on campus at that time. I think, like a lot of other people who have been in the service, you’d been delayed in what you were doing. You wanted to catch up and the best way to catch up was to move as fast as you could toward a degree. I did graduate with a bachelor’s degree in civil engineering in 1948. But I decided I wanted more education and I had to make a choice between starting law school, which was interesting to me, and going for a graduate degree in engineering. I think I finally chose the graduate degree in engineering primarily because it only took one year and law school took three years, and I felt the pressure of being a little behind—although I was just 22.

Your next involvement with the UW was working in the Legislature. How did that happen?

I got called back into the Navy during the Korean War. I really got to a point where I thought maybe I would want to be involved politically. I wrote a letter to my father and went on to really berate what was going on nationally. We couldn’t win and we were engaged in the stalemate in Korea and all of that sort of thing, and all of that angst of a young naval officer. And I said in that letter, “If I were only back in Seattle, I would run for the Legislature.” I wrote the letter and sent it off and totally forgot about it. My father put it away in a little box he kept on the top of his dresser and didn’t show it to me until after I became governor.

Evans is sworn in as governor for the first time in 1965. He was later named one of the top 10 governors of the 20th century in a University of Michigan study.

Tell me about your first election.

When I came back from Korea, I got back into engineering design, but also volunteered to work for the Republican Party. I went to work on organizing the 43rd Legislative District … In 1956, Mort Frayn, who had been speaker of the house and lived in that district, retired. So there was an opening …. Not only did I win the contested primary and general election, but I ran ahead of the other incumbent, so it was a great start politically.

What were the issues in Olympia that impacted the UW in those days?

We were just at the end of what had been a rather tough kind of thing for the University of Washington and that was when they got into the loyalty oaths, and they had several University professors who were fired.

The Canwell hearings …

The Canwell hearings. And those had just about run their course, but it really damaged and hurt the University and the University was in the process of recovering …. In those days, interestingly enough, there was pretty good support for the University. At that time, the whole idea in the Legislature was to provide sufficient support to the universities to keep tuition extremely low. And if they could have found enough money to do it, they probably would have gone back to the theme of the early days of statehood. When they moved to the new campus from downtown, the bill that authorized a new campus said, among other things, “that tuition for all bona fide residents of the state of Washington shall be free.” They understood the broad importance of higher education, I think, to a much higher degree than legislatures do today.

What’s changed in the years since then?

The competition for tax money has grown extraordinarily. During the time when I was in the Legislature, we had prisons, but nowhere near to the same degree did we incarcerate people. We have gone on a binge. Everybody loves the idea of “three strikes and you are out” and being tough on crime. Sometimes they don’t understand the price you pay for being that tough on crime—incarcerating people who might be helped better by treatment or something else. Every dollar you put there, you have to take away from something else. For every person you put in a Washington state prison you could cover three tuitions at the UW. To me, that is a bad trade. The other thing is the cost of health care. It is just consuming tax money to the extent that everything else is in trouble.

As governor, you accomplished many things, but if you had to limit it to one thing in higher education, what would it be?

The most significant thing that happened in the 12 years that I was governor was the development of the state community college system. When I first became governor, there was a flood of war babies who were now going through high school and facing higher education. We did not have nearly enough space for them in the four-year institutions.

I might say that in retrospect, looking at where the community college system is today, I think we may have gone too far. The community college system is so big, so broad, so consuming of tax money. That has really kept back some of the necessary support of four-year institutions and post-graduate work that now is an economic necessity. So priorities have changed in 30 years and we haven’t yet responded.

One of my most vivid higher-education memories from my days in your office came during those antiwar demonstrations around 1970. You were in constant contact with the UW. Could you reflect on what was happening?

There was a growing tide of opposition to the war in Vietnam and it was primarily among the young. After all, they were the ones who were fighting the war. There were increasing demonstrations. When I see a demonstration today on the University campus and the students think it is a big demonstration, I just smile. It is nothing like the almost 10,000 students who one day marched to the federal courthouse downtown and used the freeway to do it. It was a massive demonstration, but one that was, for the most part, very peaceful. A couple of students at the end of the march threw bricks through a couple of plate glass windows downtown. The news that night made it sound like 10,000 students from the University trashed downtown.

I got hundreds of letters from people, mostly really bitter against the students. That’s when I went on television. KING-TV offered me a half hour to talk with our citizens.

I did it just with a few notes and a sample of some of those letters, trying to just calm everybody down, because it was getting pretty hot. I met with student groups frequently. And they were all pretty great at acting out vocally and marching and that sort of thing, but they generally had the right ideas. Maybe they had a somewhat bizarre way of showing it, but they were against the war—which was increasingly a bad war. They were for greater opportunities in civil rights and for minorities and people of color, and they were right. It was not only interesting but I think it certainly impressed me and might have even changed my attitudes.

Who were the leaders you were working with at the University of Washington in those days?

Charles Odegaard was president and I thought did an absolutely magnificent job. He was a medieval historian. And he could talk the leg off an ox, I’ll tell you, but he understood what was going on. He was strong enough, so he didn’t let students run the University, but he was wise enough to listen to what they were saying and make changes where changes seemed to be appropriate …. A lot of university presidents in those days really collapsed under pressure … or they reacted in the other way like at Kent State and tried to get tough without listening.

When you left the governor’s office after three successful terms with a national reputation, many people were surprised that you accepted the presidency at Evergreen State College. Why?

I had always been interested in higher education. I did not consider myself an academic at all, but at the time after about seven years of existence, Evergreen was beginning to prove itself as a remarkable educational institution. But it had not yet proven itself to the legislators, to many of the high school counselors and even to some potential students in the state. I figured, well, that is something that I can help on, and doing it was a real challenge. I think I helped save Evergreen. We had some great legislative support in building an institution that now has a national reputation.

I remember that you always thought partisan politics was tough, but after being a college president, you thought academic politics was tougher.

It starts with the fact that higher education cherishes shared governance. The faculty really believes that they are the heart of the university. The students also think they are the heart. Administrators aren’t sure, but shared governance means that we got a totally different kind of institution. Former Secretary of State George Schultz put it very well. He served in private industry, in government and in higher education. When asked what’s the difference, he said, “In private enterprise you give an order and expect it to be carried out. In government, you give an order and hope that it will be carried out. And in higher education, you give no orders.”

In 1983 you were appointed to Scoop Jackson’s seat and later won it in a special election. You were in the United States Senate for five years. Were you involved with higher education at all?

Oh, sure. In issues that related to budget mostly, I was trying to ensure that there was substantial and continuing support of research in higher education.

The University of Washington has consistently done well on federal grants. Why?

Because it has a superb faculty.

These are all awarded on a competitive basis.

And so we are competing against Stanford and Harvard and Michigan and all of the fine universities in the country on every one of those grants. And we are just very good …. The faculty are willing to work together and create interdisciplinary groups.

You retired from the U.S. Senate. Two years later you were appointed to UW Board of Regents. Looking over your 12 years on the board, what would you say are your significant accomplishments?

The most important job of a board of regents (or a board of directors for a company or a nonprofit) is selecting leadership. You set policy, but you don’t run the place. In fact, boards that try to run organizations generally run into disaster.

We had, during my 12 years, two chances to select new presidents. I served in the last years of Bill Gerberding as president, and he was a superb president …. Frankly, we thought we’d done a good job in selecting Dick McCormick and he turned out not to be the right president for the University. It wasn’t that he was bad, but he ran into some problems and he lost the confidence of the Board of Regents.

We then went into a new search. We did the search twice because we weren’t quite satisfied at the end of the first one. At the end of the second search, Mark Emmert was selected. I have every expectation he will be a president in the mold of Charles Odegaard and Bill Gerberding. I hope he stays with the University the same length of time, and I am confident he will take the University to that next level.

The next level above us now is to be in the half dozen best public universities and in the top 10 of all universities in the country. I think that that is very much achievable.

The UW had its troubles when you were a regent. Football Coach Neuheisel was fired for participating in college basketball betting pools. The volunteer team physician for women’s softball was caught distributing drugs without a prescription. And the UW’s physician groups had to pay $35 million to settle billing fraud charges in Medicare and other programs.

We ran into problems. Each member of the Board of Regents was assigned different areas of the University to pay special attention to and mine happened to be medicine and athletics. And it was during this time that we had all of the extraordinary problems.

But it was a challenge that was very useful. I worked hard on the billing problems at the University. I still believe very strongly that the University was unduly penalized and that there was not sufficient understanding of both of the complexity and the difficulty of the billing process. The challenge from the U.S. attorney, I just think, was that they wanted a pelt on the wall rather than really what would have been appropriate under the circumstances. But we lived with what we had to do. We were under the kind of situation where it would have cost more, with much more difficulty and time spent, to take it all the way to court, even though I thought we were right.

On athletics, I think what happened is that athletics itself grew rapidly into the monster that it is today, nationally. It has become obsessed with big-time money. I think it’s out of control. Nationally, we need to rein in the amount of money spent on athletics. But Barbara Hedges, I think, did a good job as director of athletics. She created a whole new set of facilities. But the job finally got just too darn big.

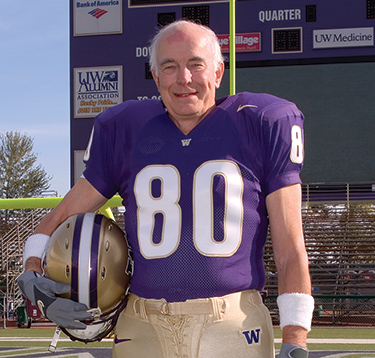

Evans suits up in a Husky football uniform as part of his 80th birthday celebration. Photo by Mary Levin

Are athletics under control today?

I leave the Board of Regents with the feeling—and the expectation—that we’ve got extraordinary leadership in the President of the University. We’ve got extraordinary leadership in Todd Turner, the new director of athletics. We’ve got some extraordinary coaches. We’re really on our way to a university that recognizes the proper role of athletics—which can be a positive and a good one—as best expressed very recently in the national championship of the women’s volleyball team.

You think there is a proper balance between athletics and academics?

Mark Emmert happens to be a very, very strong president. He also understands and is deeply involved with athletics and isn’t likely to let that get out of hand. But he will also be a real supporter of athletics as the needs require. He says it very well. He says that for many, many people, athletics is the front porch of the University. You will see a whole lot more ink spilled and a whole lot more time spent by the electronic media on athletics than you ever will on all of the academic activities of the University.

There has been a steady decline in state support for higher education over the past 20 years or so. What has this meant for the University?

Nobody in the Legislature today is willing to make another investment that will require them to raise taxes. The real question currently is whether the recovery in the economy, which is providing some extra money, will allow the Legislature to make the investment that’s required in higher education. If they don’t, we will fall behind as a state, economically, in the great competition we have not only with other states in the nation, but with other countries.

The University will continue to say, “OK, help us. But if you can’t help us, or won’t help us, then we’ll have to do two things.” We’ll have to continue to raise money on the outside. We’re in the final stages of a $2 billion campaign, which is going to be successful. But that isn’t enough.

Secondly, we will have to convince the Legislature, “Look, if you cannot or will not provide the extra help that is necessary, then for heaven’s sakes, relax some of the strings.” Give us some of the opportunity to become—I guess, what you’d call a semi-independent branch of government. But it’s very difficult for them to let go.

I think the University ought to have total responsibility for the tuition that is charged; we ought to have more independent responsibility for handling contracts for buildings, for doing purchasing, for doing a lot of things where the state likes to retain a degree of control. The state likes to maintain control, but they don’t want to put any money in the pot. It’s like a poker game: You don’t put any money in the pot, you can’t play. And it’s about time for the Legislature to recognize that.

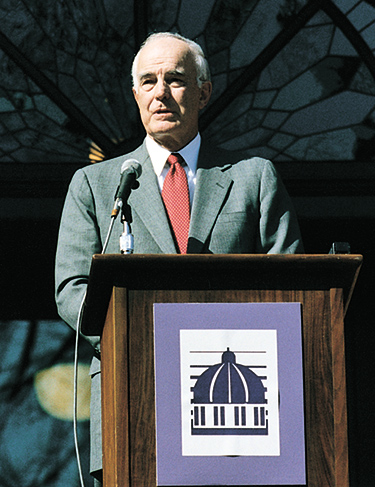

Evans speaks at the ceremony where the Graduate School of Public Affairs was named in his honor. Photo by Mary Levin.

You have the distinction of few people at the University, having a school named after you—the Evans Graduate School of Public Affairs. What is the Evans School trying to accomplish?

I asked Marc Lindenberg, who was then dean, when he first called me, “Gee, why didn’t you have the good grace to wait until I was dead?” And he said, “No, we don’t want just the name, we want you.” It’s been a great joy for me to be involved with and be part of the school, and to meet some of the students …. I want to turn out students who have great pride in public administration, and the feeling that public administration is a first-rate calling, because I believe it is. Our country was started with people who had great wealth, great success, and were willing to put all of that on the line to rake part in public activities and public administration and public enterprise, because they thought it was the most important thing they could do.

What’s next for Dan Evans?

The pressure is on for me to finish an autobiography. Whether it will be publishable I’m not sure, but it will be something, that at the very least, I’ll be able to give to my nine grandchildren.