On the day the Communist troops marched into Shanghai — May 24, 1949 — a telegram came informing me that Smith College had offered me a scholarship. By this time it was clear that the Chinese Civil War was coming to an end, and my father had decided that I should get out of the country as soon as possible. He was a successful ophthalmologist who, like most middle- and upper-class Chinese, supported the Nationalist government, and he knew that my longtime dream of going abroad to study might be lost under the new regime.

I was elated, for I was familiar with Smith College’s reputation as one of the best all-women’s colleges in the U.S. I would be a transfer student from St. John’s University in Shanghai and an entering junior. But I was nervous, too. Everything was extremely chaotic and uncertain in Shanghai, and I had no clear plan for getting out.

As the Communists’ grip on the region tightened, regulations grew stricter and my spirits began to drop. My father tried to console me and asked me not to lose hope. Being a devout Christian, he urged me to pray, and I did. Then one day in early August he called me from his office to tell me that he had found a way. He couldn’t share the details over the phone, so I waited impatiently for him to return home.

Shirley Wang (left) and Julia Lin in Hong Kong, Oct. 16, 1949, just before Shirley sailed for the United States.

I was to be smuggled out of Shanghai on a fishing boat. One of my father’s longtime patients, Mr. Li (I can no longer remember his real name), had a nephew who owned a good-sized fishing junk that regularly ran supplies between Shanghai and the Zhoushan Islands — a group of small islands still occupied by the Nationalist government. My father had asked Mr. Li if his nephew would be willing to take me and my best friend, Shirley Wang, onboard his junk so that we could escape to the states. The nephew had agreed. Shirley, whom I had known since we were seven, had been offered a scholarship to Flora MacDonald College in North Carolina, and was just as eager to get out as I was. We would pose as relatives of the Li family returning to the islands for a visit. From there, we could gain passage to either Hong Kong or Taiwan, and then to the states.

In the days before our departure, our faithful longtime housekeeper, Liu Ma, a woman who had helped take care of me since I was 10, meticulously sewed several documents (such as the Smith telegram) into the high collars of my dresses, and inside my Chinese cloth slipper shoes. They would make it easier for me to obtain a passport and visa later on. She also sewed in two American $10 bills. Meanwhile, I worked hard to memorize the names of two Nationalist generals who would help get us to Hong Kong or Taiwan. We dared not write down their names for fear of being discovered by the Communists.

Opposite, above: Julia Lin’s father, FuXing Zhang, her stepmother, MoXi Zhou, and her half-sister, Irene, photographed in China in 1951.

The first leg of our long journey would be hazardous: the Nationalist government’s resistance forces continued their relentless bombing of Shanghai and the coastline throughout the summer of 1949. So we had to wait for a day when the bombing had subsided. Finally, one August morning before dawn, my two younger brothers Yong and Heng saw us off near where the junk was docked. We couldn’t even acknowledge each other openly; we had said our goodbyes the night before at home.

It was a sad farewell. Ever since my mother’s death when I was seven, the three of us had been very close. I was the big sister who tried my best to look after them. Now I felt I was abandoning them. I felt even more guilty about leaving my father and my maternal grandmother, Hao Po — two people I loved the most. Although I did not know it at the time, it would be three decades before I would see my brothers again, and my dear Liu Ma. And I would never again lay eyes on my father or my grandmother.

That day, though, there was also a sense of relief, anticipation and joy. I dreamed of studying English literature at an American university, then returning to teach in Shanghai, introducing to my students the great literary traditions of the West. And I dreamed of seeing the wonderful cities of the Western world — London, New York, Paris, exotic places that I had read about in so many books.

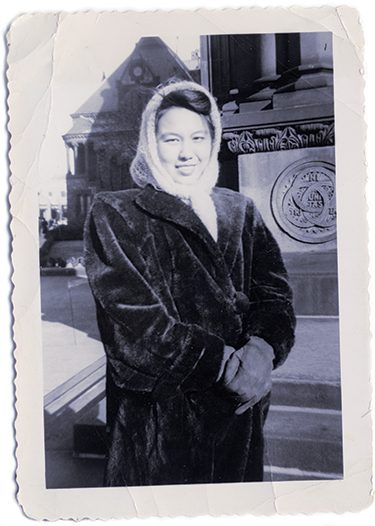

Lin’s first winter in New England, 1949 or 1950.

Our captain was a memorable-looking young man, muscularly built and weather-beaten to a dark tan. From a distance, his boat appeared to be a fairly good-sized fishing junk. But as soon as we got onboard, we discovered the living quarters were quite cramped. It was a small cabin with four berths — two upper and two lower. Mr. Li and his daughter, who were returning to the islands, occupied two of them. The remaining pair was used by a banker and his pretty young mistress. Shirley and I would sleep on the floor.

Disappointment, sadness and fear all gave way to excitement as we prepared to embark. But at daybreak the bombing resumed, and quickly turned fierce. Our boat shook, and the noise was so deafening that I had to cover my ears. Both Shirley and I were petrified that one of the bombs might hit our junk and kill us all. By the time the captain felt safe raising the sails, it was nearly noon.

We quickly reached the customs checkpoint, where officers came onboard to examine everyone’s exit permits and see if the boat was smuggling anything. As luck would have it, one of the officers immediately recognized Shirley, whose father had worked for the customs service department all his life. Since we were supposed to be the relatives of these island people, Shirley denied that Mr. Wang was her father. I felt helpless; I was not quick-witted enough to think of a way to help poor Shirley out of this dilemma. Her denial immediately angered the customs officer, who became very hostile toward us. He searched our suitcases, in which we had packed clothing and things we would need in college. I’m sure that the officers were aware of the true nature of our trip. But they didn’t find anything incriminating.

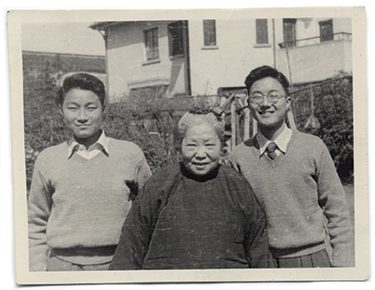

Lin would not see her younger brothers, Heng (left) and Yong, for 30 years. She would never see her grandmother again.

When they went to the galley, however, they discovered quite a few small gold pieces in the ashes of the stove. The officers accused us of smuggling this gold to finance our journey. Speaking the truth, we both vehemently denied this. In fact, these gold pieces belonged to the banker, as we later found out, although he didn’t volunteer his ownership at the time. The officers arrested the captain and took him ashore. We waited from noon to evening, not knowing what would happen next. Shirley and I were particularly distraught — worried that they might come back to arrest us as well. It was a huge relief when the captain returned to the junk alone. He had been able to convince the officers that the gold pieces did not belong to us, and had gotten off with a fine.

That first night onboard the ship turned out to be another ordeal. Soon after Shirley and I bedded down on the cabin floor, we discovered to our horror that it was covered with ugly yellow worms. They must have crawled over from an adjacent cabin where some kind of dry edibles were stored. Shirley and I were too squeamish to share our sleep with these repulsive-looking uninvited guests, so we sat on the few narrow steps that led from the cabin to the deck. Naturally we had a fitful night, despite our exhaustion.

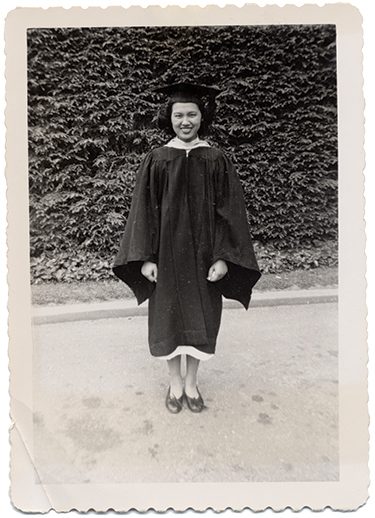

Lin graduated from Smith College in 1951. She came to the UW that fall.

The following night brought a terrible summer monsoon, which caused the boat to pitch and toss for hours. Sitting on the steps that led to the deck, exposed to the downpour, both Shirley and I got soaked. Later that night, something even more frightening happened. The captain suddenly shouted at us to get down to the cabin. We obeyed immediately, and soon heard a huge commotion on deck, followed by the loud staccato of a firing machine gun. Our crew was shooting at an approaching boat! Shirley and I both shook with fear. We saw the mistress of the banker clinging to him, trembling, as well.

Later, the captain told us it had been a pirate boat advancing on our junk. He explained that these pirates, knowing how many rich people were trying to escape from Communist-controlled Shanghai, would ambush boats and rob passengers. Sometimes the nasty ones would gleefully dump their victims into the sea. After the smoke had cleared, I found myself wishing I had snuck to the top of the stairs to watch the whole scene — the approaching pirates, and our brave crew firing at them. But I didn’t. I must have been more frightened than I admitted to myself.

After three days and two sleepless nights at sea, we finally arrived at the Zhoushan Islands, where Shirley and I were shocked to learn that we couldn’t leave the junk with our hosts, Mr. Li and the captain. We had to remain onboard for another night while Mr. Li went ashore to get permission for us to disembark. The captain told us that the Communists were rumored to be using young women students as spies, so the authorities on the islands were especially wary of people like us. Our disappointment, however, was mitigated by a good night’s sleep in the now-vacated berths! It was our first real rest in three days. The following day we were overjoyed to see old Mr. Li and our captain returning to the ship to bring us ashore.

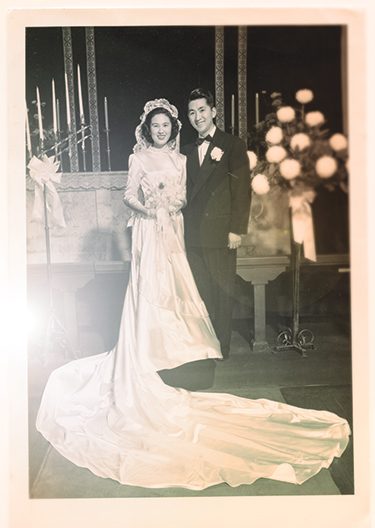

Julia and Henry Huan Lin met at the UW, and were married at Christ Episcopal Church in the U-District, Dec. 28, 1951.

I often wonder: if my father had been told of these hazards, would he have allowed us to make the voyage? I also wonder whether Shirley and I would have been so eager to be smuggled out of Shanghai if we had known of the dangers involved. I suspect we would have. It was scary — but exhilarating, too. And I know neither of us ever regretted our decision to go. My one heartbreaking regret, of course, is that I never had the chance to see my father or grandmother Hao Po again. By the time I was permitted to return to Shanghai in 1979, they had passed away.

Even after we arrived at the islands, our escape was far from complete. The two generals whose names I had so assiduously memorized were nowhere to be found. For all I know, they never existed. For more than a month, while living with the family of Mr. Li, Shirley and I cast about for a contact who could help us get closer to the United States. Eventually, through the intervention of a kind minister, we found our way to the most powerful man on the islands — the chief of the Nationalist government’s secret police. With his guidance, we were able to secure passage to the port city of Xiaman, then Hong Kong, and finally to the U.S. To this day, I marvel at his eagerness to help two unimportant young students continue their journey and, eventually, their education. I know that without the kindness, generosity and concern of many individuals, including many total strangers, my dream of pursuing my education abroad and seeing the world could never have come true.

Years later, after the University of Washington Press published my first book, my father wrote me a most loving letter, telling me he felt blessed to have a daughter who through determination and effort had produced such a splendid work. When I began teaching Chinese literature he sent another letter, saying how pleased he was that instead of introducing great Western works to students in China, I was introducing magnificent Chinese culture to students in the West. Though he never said it outright, I have always felt that these were his ways of letting me know how happy he was to have gotten his beloved daughter out of China — even at such a great and permanent cost — and to see her fulfilling her dreams in a new life, on a new continent.

Epilogue

Lin with her daughter Maya, outside the president’s home at Smith College in 1993. Maya was receiving an honorary degree.

Shirley attended college in North Carolina for only a semester before winning a scholarship to study piano at the Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore. She went on to become a celebrated concert pianist, giving solo performances in Carnegie Hall. Julia finished her bachelor’s degree at Smith, then came to the UW, where she earned a Ph.D. in Chinese language and literature. Her thesis adviser was so impressed by her dissertation that he arranged for its publication by the UW Press. In 1951 Julia married Henry Huan Lin, ’57, a graduate student and a talented artist. Both would eventually join the faculty of Ohio University, Julia in English and Henry in ceramics. Henry went on to serve as dean of the OU College of Fine Arts. He died in 1989. Julia retired in 1999, and in 2005 moved to eastern Pennsylvania to be closer to her two children, Tan and Maya, both of whom live in Manhattan. Her latest book, An Anthology of Twentieth-Century Chinese Women’s Poetry, will be published next year.