Revolution to evolution Revolution to evolution Revolution to evolution

Emile Pitre captures the story of decades of activism at the Office of Minority Affairs & Diversity in his new book.

By Hannelore Sudermann | February 23, 2023

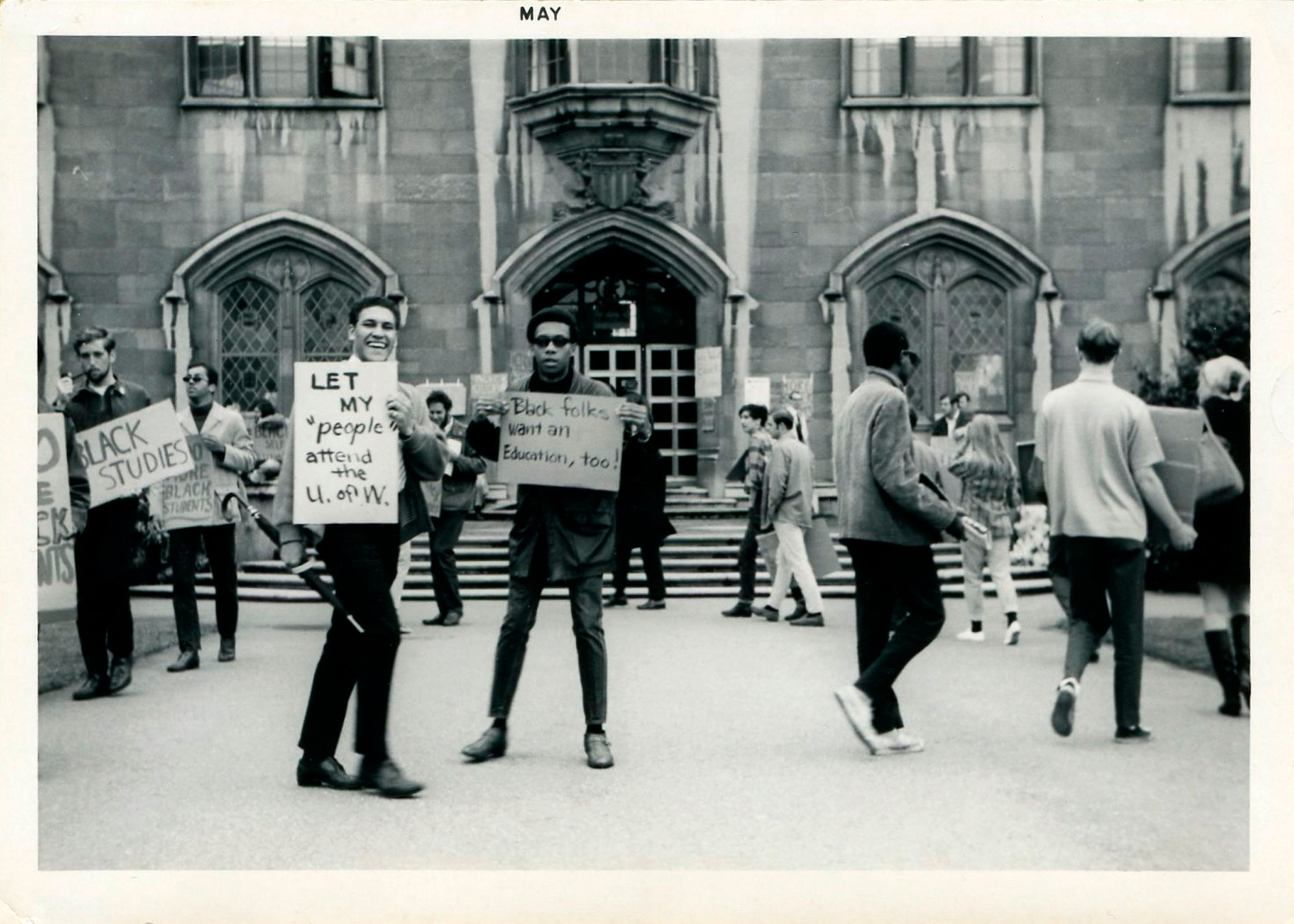

Lead photo: Garry Owens, center, and Jesus Crowder, left, were among the activists who demanded the UW enroll and support a more diverse student body. Their activism and input led to the formation of the Office of Minority Affairs & Diversity and made the University more accessible to future generations of students. Photo courtesy of Steve Ludwig II.

Campus diversity is no longer a revolutionary idea. But it certainly was in the late 1960s and early ’70s when a small number of student activists and an even smaller number of faculty and staff pushed the University of Washington to serve all of the state’s potential college students.

With sit-ins, protests and a list of demands, the activists—led by the Black Student Union—insisted the UW recruit and support a multiracial, multicultural student body, hire faculty of color and expand the curriculum to be more culturally diverse. Through their activism, their vision and their continued engagement, they forged a new future for the UW and influenced the trajectories of generations of students.

Now, Emile Pitre, ’69, one of those early student activists and a longtime member of the UW staff, has captured the story of the decades of work in his new book, “Revolution to Evolution: The Story of the Office of Minority Affairs & Diversity at the University of Washington.” He blends research and interviews with his own insights and memories to offer a comprehensive chronicle of one of the first diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) programs in the country.

After describing the formative years of diversity work at the UW, Pitre fills in the eras, capturing the turbulence of the late 1970s and 1980s when administrators tinkered with admissions practices which led to protests, arrests and staff resignations. The 1990s brought state-mandated changes to enrollment policy that prohibited the consideration of race or gender in admissions. Instead of allowing the rule to thwart their efforts, the staff adapted, “and we kept moving,” Pitre says.

He also shines a light on colleagues who were driven to support students and undo structural and cultural racism across campus. Their efforts resulted in thousands of student successes. Erasmo Gamboa, ’70, ’73, ’84, for example, was one of the first to be recruited to the UW in late summer 1968. He remembers when a group of Black UW students drove into the city of Toppenish to find prospects for the new program. “They told us if we were interested, they would help us get in,” says Gamboa, who hadn’t imagined attending the UW.

Gamboa arrived on campus to join what was then called the Special Education Program and is today known as the Educational Opportunity Program (EOP). While he wasn’t high-achieving in high school, Gamboa graduated from the UW with honors. He stayed to get his Ph.D. in history and, as a member of the faculty, became a leading scholar of Latino history.

In the book, Pitre calls out many more alumni successes including the current U.S. Poet Laureate, Ada Limón and Anisa Ibrahim, director of the Harborview Pediatrics Clinic. “It was an EOP counselor who truly believed in my dream to become a doctor and gave me practical steps to ensure my success,” says Ibrahim, whose family fled the civil war in Somalia and settled in Seattle when she was just 6. “I would not be where I am today without the [OMA&D] Instructional Center. I have never seen a more dedicated group of educators. They not only cared about our success as students but also cared about us as individuals. After a long day roaming campus, many of us referred to going to the IC as going home.”

“This is a significant book because it speaks to what is possible when programs and services are designed with- underrepresented and underserved students in mind,” says Rickey Hall, vice president for Minority Affairs & Diversity at the UW. As one of the first DEI offices in the country, it has an important story to share, he adds. “Hopefully other institutions will see what’s possible with intentionality and investment.”

In 2013, students rallied for a requirement that all undergraduates must take at least one course that focuses on sociocultural, political and/or economic diversity. Photo by Emile Pitre.