Healthy babies, healthy moms. Those are Rebecca Moore's goals. As a "doula," the Port Orchard mother of three helps expectant parents plan for their child's birth and often coaches the mother through labor.

“I try to inform them ahead of time about medications and their surgical options,” she says. “Basically, I want them to be informed if they are faced with these decisions. That’s what it’s all about, making good decisions.”

One of the biggest decisions facing Moore’s clients is how their baby will be delivered. Should they try for a vaginal delivery, or schedule a Caesarean section? And what about the use of forceps or vacuum extraction? What method will mean the least risk to both mother and child?

Since the 1980s, most studies on childbirth have focused on the ways that different delivery methods affect the baby’s health. Now a group of UW researchers are looking at how those methods—especially Caesarean sections—affect the health of the mothers.

“There’s been very little research on the impact of the birth on the mother’s health after delivery,” says lead author Mona Lydon-Rochelle, a senior research fellow in the UW School of Nursing.

Mona Lydon-Rochelle

Controversy about the risks and benefits of Caesarean sections, or C-sections, as they are commonly called, has raged for more than a decade. Between 1970 and 1988, the Caesarean rate skyrocketed from 5 percent to nearly 25 percent of deliveries in the United States.

In May, Lydon-Rochelle and her team published a study in The Journal of the American Medical Association on links between delivery and rehospitalization. While only a small percentage of Washington’s new mothers—1.2 percent—are rehospitalized within two months of delivery, mothers who deliver by Caesarean section are 80 percent more likely to be among that group.

For mothers with assisted vaginal delivery, the risk of going back into the hospital was 30 percent higher. That’s even when the mother’s age, medical history and pregnancy complications are taken into account, says Lydon-Rochelle.

“To be hospitalized with a new baby at home is an enormous problem,” she says. Rehospitalization “carries substantial consequences including high economic costs. It disrupts early parenting and increases the family burden.”

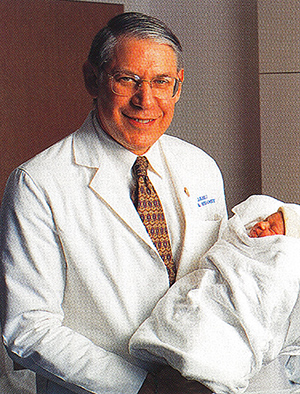

While the percentage of births by C-section has stabilized—it was 21 percent in 1998—controversy about the procedure has not. Steven Gabbe, chair of the UW’s Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, can tick off a list of reasons for the increase since the 1970s.

“The first one is that we stopped doing vaginal breech deliveries,” he says. Long labor came to be seen as riskier labor. Physicians began intervening more when labor failed to progress.

The advent of the fetal heart monitor and fears of malpractice litigation also contributed to the jump. As the number of first-time moms delivering surgically increased, so did the number of subsequent Caesareans. While some viewed the procedure as safer for the baby, women’s health advocates and critics complained that doctors were overusing the procedure.

From the insurers’ standpoint, there was also the issue of expense. In 1998, the Washington Department of Health found the average cost of having a healthy baby by vaginal delivery was $3,642. Delivering the same baby by C-section averaged $7,458. And neither figure included doctors’ fees.

When the federal Department of Health and Human Services launched its Healthy People 2000 Initiative a decade ago, one of its goals was to reduce the overall Caesarean rate to 15 percent by 2000.

Steven Gabbe

But as the deadline approached, the overall rate was about 21 percent, and the target came under heavy fire from the medical community. Critics, including Gabbe, believe there is no data to support the agency’s ideal rate. Some see cost cutting efforts by insurers and HMOs as the driving force behind the effort. They maintain more research is needed into the risks, especially for women attempting a vaginal delivery after having had a Caesarean.

“There has been so much pressure to shorten the stays,” Gabbe says. “Doing more C-sections lengthens the hospital stay for the mother.”

Even researchers with the federal project acknowledge that some medical facilities and health care plans took the target as an absolute rather than adapting it to their communities. Renee Schwalberg, a researcher who is helping develop Healthy People 2010, says the latest initiative tosses out the overall target and instead focuses strictly on targets for low-risk pregnancies.

“The main objective was always to focus on low risk,” Schwalberg says. “If a fetus is breech, you need a C-section. These cases are outside the objectives.”

The new proposal calls for a Caesarean rate of 15.5 percent for first, full-term, single births and a rate of 65 percent for women with a prior Caesarean. The national health care system still has a way to go. In 1998, the C-section rate for first-time single births was 18 percent and women with a prior Caesarean 72 percent.

According to Gabbe, physicians are rethinking Caesarean sections. There is some evidence that there may be more complications than were previously thought for women who attempt vaginal delivery after a Caesarean. There is also a rapidly developing body of research on injury to the pelvic floor during vaginal delivery which could cause later problems such as incontinence.

As the pendulum swings back and forth, a growing number of physicians and researchers are suggesting that women should be able to opt for scheduled Caesareans.

“You think research is supposed to answer questions, but it doesn't. It poses new ones.”

Thomas R. Easterling, obstetrics and gynecology professor

Benson Harar Jr., president-elect of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, this year posed the idea that the risks and benefits of Caesareans and vaginal delivery are balanced enough to perhaps allow women to make a choice. In June, New York OB/GYN Jennie Freiman was featured in the women’s fitness magazine, Self, describing why she chose to have both her children by scheduled Caesareans.

In her article, Freiman noted that the bulk of deliveries, vaginal or Caesarean, are safe for mother and child, but when complications do occur in vaginal deliveries, those complications are more likely to harm the baby. Facing first-time motherhood at age 37, Freiman says she preferred to be the one to take any possible risks.

Pam Udy, education director for the International Cesarean Awareness Network, worries the new trend is already discouraging health care providers from offering vaginal delivery to women who have had previous Caesareans.

Udy, 29, was 36 weeks into her pregnancy when she dropped her longtime obstetrician rather than deliver a third child by C-section. She interviewed three doctors before finding one who would agree to let her try a vaginal delivery.

“I have video of all three of my sons being born,” says Udy, “but in the first one, everyone got to see him except me. I’m nowhere to be found because I’m still in surgery.”

Approximately 4 million babies are delivered in the United States each year. For the UW study, researchers dug into the state’s birth record database and compared 256,795 delivery records from 1987 to 1996. The study considered only first-time mothers who gave birth to single, live infants. Mothers with preexisting medical problems such as diabetes, chronic hypertension and other conditions that might make operative deliveries more likely were excluded.

While doctors have known for years that different forms of delivery might lead to complications, the rehospitalization study became the first to report on hard data—and reasons for the complications. For example, women who undergo assisted vaginal deliveries, such as those using forceps, run a greater risk of being rehospitalized for postpartum hemorrhages.

Obstetrics and Gynecology Professor Thomas R. Easterling, a co-author of the study, says one of the most surprising results was the link between Caesarean sections and rehospitalization for gall bladder disease.

“You think research is supposed to answer questions, but it doesn’t. It poses new ones,” Easterling says. Some studies have linked abdominal surgery and the development of gall bladder disease to dehydration, fever and anesthesia. Those same elements can be associated with Caesareans.

Researchers were also surprised to see an 80 percent increase in risk of rehospitalization among C-section mothers due to appendicitis, perhaps as a result of manipulation of the abdominal contents during delivery.

While C-section mothers were twice as likely to go back in the hospital compared to those who have vaginal deliveries, their rate of rehospitalization was still markedly lower than the rate following hysterectomies.

The most notable finding was a 30-fold increase in the risk of wound infection among women who undergo C-sections, researchers say. Since every Caesarean involves surgery, the result was not a surprise, but it did spur a call for clinicians to take more preventative steps such as limiting the number of vaginal examinations during labor.

“This study gives all of us as practitioners food for thought,” Easterling says. When other UW studies are completed, they will provide patients and the medical community with a broad look at mothers’ delivery risks.

Lydon-Rochelle believes the strength of the research project is due in large part to the team’s interdisciplinary nature. Co-author Victoria Holt is a professor of epidemiology; Diane Martin is a professor of health services.

“What one doesn’t think of another one does,” she says. “It really strengthens the work.”

The study recommends the use of safe, clinically appropriate steps such as a larger role for midwives and second-opinion requirements to reduce the likelihood of first-time C-sections.

The researchers are now using the same statewide data to look at other measurements of maternal health. A report on possible links between delivery methods and mortality rates for new mothers is due out this fall.

They are also planning to look at the relationship between a woman’s first delivery and possible problems with the placenta during her second birth. A fourth study will focus on second births and the dangers of rupture among women who have undergone Caesareans.

“Hopefully, it will trigger more discussion and more fine-tuning of the research,” Lydon-Rochelle says. “You want everyone to have a good outcome. The way to do that is to figure out who is a good candidate (for vaginal delivery) and who isn’t.”

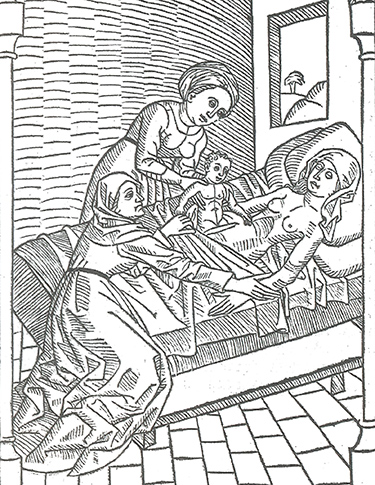

C-sections through history

A 15th-century German woodcut depicts Caesarean childbirth.

The origins of the Caesarean section’s name—like the rest of the operation’s history—remain shrouded in mystery and debate.

Popular legend attributes it to the birth of Julius Caesar, claiming the Roman Emperor was cut from his mother’s womb. This account has met with some skepticism since his mother is reported to be alive at the time he invaded Britain.

Some scholars say the phrase springs from the Latin verb “caedare,” meaning to cut. Still others believe the name comes from the Roman decree that required the procedure be used to save infants whose laboring mothers were either dead or dying.

The concept of surgical delivery, whatever its origin, has been recognized around the world for hundreds of years. According to historian Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski, the oldest description of a Caesarean birth appears in a cuneiform tablet from Mesopotamia dating back to the second millennium B.C.

Folklore holds that babies born by Caesarean section are tied to the mystical and are said to possess extraordinary strength. The Greek gods Adonis and Bacchus were both born by Caesarean section, as was the medieval hero Tristan. Pliny the Elder wrote in his Natural History of the auspiciousness of a Caesarean birth.

If early literature rarely mentions the mothers, it’s because they died. The first written report of a mother and child surviving finally comes in 1500 when Swiss pig gelder Jacob Nufer sought permission from authorities to operate on his wife after several days of fruitless labor.

Francois Rousset, an early proponent of Caesareans on living women, wrote later that Nufer made a single deep cut and extracted the child on the first try, then sewed his wife up in the same manner he used with his animals. The following year, she supposedly gave birth to twins, this time without surgery.

Western medicine had no monopoly on the procedure. Jane Eliot Sewell, who penned a history of the Caesarean section for the National Library of Medicine, cites 19th century accounts of successful surgical deliveries in Rwanda and Uganda. African healers used botanical preparations to anesthetize their patients and promote wound healing.

Breakthroughs in anesthesia, antiseptics and antibiotics over the past 200 years have been the keys to saving both mothers and children. Reminders of that rapid change can be found in state historical markers like the one outside Donaldsonville, La., which salutes the town as the home of Dr. F.W. Prevost, who “performed first Caesarean section, 1824.”

Childbirth tips

Good medical care grows out of good communication, experts say. Here are a few questions that expectant mothers should ask their doctors, hospitals or health insurer:

- What are my health risks and how will they affect my delivery?

- What are my doctor’s feelings about natural childbirth? About Caesarean sections? About vaginal births after Caesareans?

- What services will my health insurance cover? If I have already delivered a baby by Caesarean section, must I attempt vaginal delivery for another Caesarean to be covered by insurance?

- Are there any limits on having my partner, or other support, with me during labor and delivery?

- If I develop problems during pregnancy or delivery, how will my care be managed?

- How long will I stay in the hospital after a normal birth? What about after a Caesarean?

Source: Washington State Department of Health’s Pregnancy and Childbirth Guide to Hospital Charges.