“Think of all the young people out there who don’t have a clue to what the labor movement has meant to them. They take for granted such things as paid vacations and the 40-hour work week, protections from injury on the job, sick leave and pensions.”

— Victor Kamer, guest editorial, Sept. 11, 1989, Newsweek

Students at the University of Washington are no different from those described above, says Political Science Professor David Olson. “I teach ‘Introduction to American Government.’ The knowledge about what unions are, what their historical role has been, the place they've had in the area of social justice is non-existent in this generation of students.”

Olson hopes to do something about this general ignorance as the first holder of the Harry Bridges Chair in Labor Studies at the University of Washington. Named in honor of radical union organizer Harry Bridges, this chair and its Center for Labor Studies functions as a clearinghouse for information on workers and the trade union movement.

Many universities dump labor studies in a business school’s center for “industrial relations,” a place where future managers are taught “how to finesse or bust unions,” Olson notes. Then there are “schools for workers,” the most famous being at the University of Wisconsin, which tutor future union organizers.

The UW Center for Labor Studies is not going to follow either path, Olson says. The center will educate UW students on all facets of labor, “the history of labor, contemporary labor developments, the contribution of labor to society, pay equity issues and so forth,” and address both non-union and union workers.

Students will learn, for example, that Washington state is one of the top states in the nation in terms of union membership compared to total population. With a labor density of about 33 percent, only New York, Michigan and Washington, D.C., have more union members per worker.

Olson says the number one reason for such strong membership is the many unions at Boeing, such as the machinist and the engineering unions. Also contributing to this strength is a historical tradition of union involvement in social and political issues.

Unions in the Pacific Northwest did not follow the “business agent” approach of organizing only on wage and job-site issues, Olson says. “The tradition of the Wobblies, the Grange and the Progressives” brought a more encompassing union movement.

Finally, adds Olson, “union membership among the middle class in Washington state is not a negative thing,” in contrast to much of the rest of the nation.

Across the nation, unions are in trouble, Olson warns, and have been for decades. Union membership as a percentage of the non-farm labor force peaked in 1953 at 33 percent. Today it hovers around 16 percent.

Much of the decline is blamed on the shrinking manufacturing sector, traditionally a union stronghold. Indeed, over the last three decades, the only growth in union membership has come from the service sector, mostly in government jobs such as police, firefighters and teachers.

“It is not a good time for labor. It hasn’t been a good time for the last 30 years.”

David Olson

Olson adds that union leaders made many mistakes, compounding the decline. Some bosses, such as the

Teamsters’ Dave Beck and Jimmy Hoffa, had regimes rife with “nepotism, corruption, inflated salaries, perks and sweetheart deals with business,” charges Olson.

Unions won’t adapt to the changing economy, he adds. “They are less responsive and innovative with respect to white-collar employees and new industry, particularly high technology industries.”

Finally, unions have done a bad job of explaining their accomplishments to the American people. “They have a story to tell and have told it poorly, or refused to tell it at all,” Olson says.

It doesn’t help that labor unions face a “hostile” government, Olson says. While the 1930s had been supportive of unions, and government in the ’40s, ’50s and ’60s was at least neutral, “over the last two decades government has been hostile.”

President Ronald Reagan’s breaking of the air traffic controllers’ strike is a prime example, but there are many ways the federal government has crippled union organizing, the labor studies professor explains. For example, the Reagan administration imposed stricter requirements for union certification and made unfriendly appointments to the National Labor Relations Board.

Even with the election of Arkansas Gov. Bill Clinton, Olson doesn’t see a new day dawning for unions. “His labor record is a hard read. He comes from a right-to-work state (it outlaws mandatory union-member-only shops), and Arkansas has one of the lowest percentages of union membership in the country.”

Under Clinton, labor will have “a place at the table” when it comes to health care reform and free trade, Olson says. But he says there will “probably be some clash between teachers’ unions and the Clinton administration” over attempts at education reform, as there were during Clinton’s Arkansas governorship.

Until the economy improves, Olson does not see labor’s return to the heydays of the 1950s. “Labor has not done well historically in organizing during periodic recessionary times,” he explains. “Their strongest market position is when there is a real, or perceived, labor shortage.”

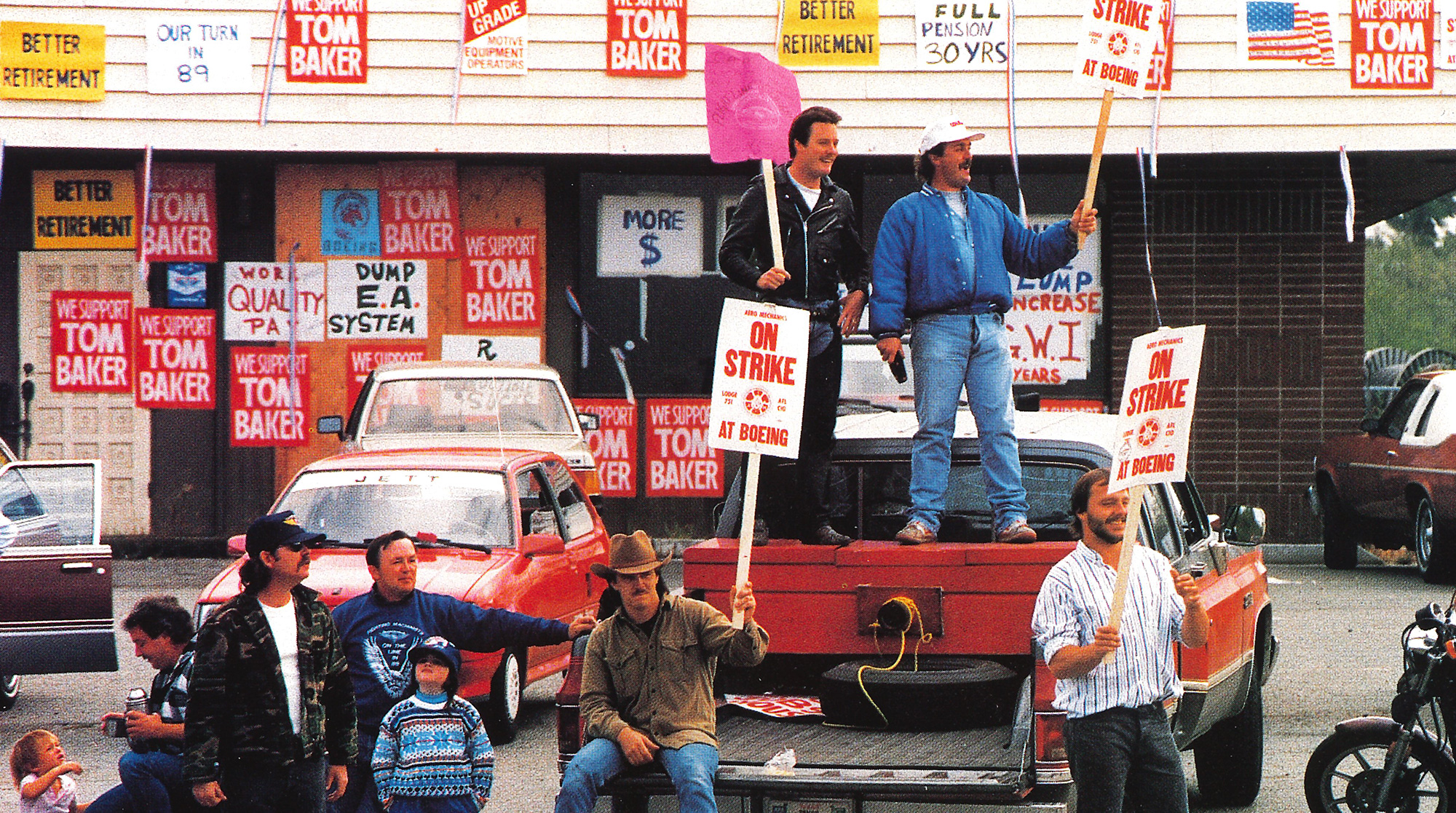

A good example of the tenor of the times is the recent series of negotiations between the machinists union and Boeing. Three years ago, during a boom in aircraft orders and a low unemployment rate, the machinists struck for a month to get a better contract.

Last September, when the contract came up for renewal, the machinists approved the new offer by 71 percent. “Boeing was strategically advantaged on this one. It could absorb a two to three month pause in work, due to the softness in the commercial aircraft market. Boeing held all the cards,” says Olson.

Some labor leaders fantasize about laid-off white collar workers joining their ranks. Former auto workers president Douglas Fraser told the press, “The people being laid off now have never been laid off before. That makes them good prospects for organizing.”

Olson disagrees. “It is not a good time for labor. It hasn’t been a good time for the last 30 years.” In fact, it may take times like those of Harry Bridges’ era—a depression on the order of the 1930s—to get labor back to its previous strength. Says Olson, “Under a great depression, workers see themselves as workers and act like workers, regardless of how difficult their lives are.”

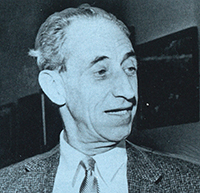

Harry Bridges

A visionary labor leader … a Communist … an illegal alien … a crusader for social justice—it seems either you hated Harry Bridges or you loved him.

Members of the International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union (ILWU) loved their late leader so much they dug into their pockets to endow a $1 million chair in his honor at the University of Washington.

Edgar Hoover hated Bridges so much that he tried to deport him back to his native Australia four times.

Born in 1901 to middle-class parents in Melbourne, Australia, Bridges’ upbringing included four years as an altar boy at his neighborhood Catholic church. Along with his religious education, he absorbed the teachings of the growing trade union movement in his native land. His seafaring life began at age 15, when he worked on ships serving Tasmania. That led to four years in the merchant marine, including a shipwreck where his father’s mandolin served as his life preserver.

In 1921, Bridges joined a strike in New Orleans that led to his first arrest and his membership in the Industrial Workers of the World, the “Wobblies.” He landed in San Francisco in 1922, gave up seafaring for dock work, and began union organizing. Two years later he left the Wobblies, but he never surrendered his radical politics.

He first rose to prominence in 1934 as one of the leaders of the waterfront strike that stopped West Coast shipping. During that strike, dock owners tried to recruit UW athletes to cross the picket lines. UW Acting President Hugo Winkenwerder prohibited UW students from becoming strikebreakers, going so far as to forbid a boat for strikebreakers from docking on campus.

Meanwhile, at the University of California the football coach sent three platoons of football players to cross picket lines on the San Francisco waterfront. Members of the ILWU never forgot the UW’s stand during those crucial weeks, and found it fitting that they could contribute to a chair at the institution that lent them support almost 60 years before.

Bridges founded the ILWU in 1937 when the unskilled workers of the CIO split off from the craft- oriented AFL. That same year he was invited to speak on campus by the University Luncheon Club. Teamsters boss Dave Beck was an AFL supporter and longtime Bridges adversary. Influential in local politics, Beck and his allies tried to keep Bridges off campus, says local labor historian Ron Magden, ’64. But UW President Lee Paul Sieg resisted the pressure and Bridges spoke in the Commons on May 14.

He de livered a fiery speech to a packed audience of 200. “We take the stand that we as workers have nothing in common with the employers,” he declared. “We are in a class struggle and we subscribe to the belief that if the employer is not in business, his products still will be necessary and we still will be providing them when there is no more employing class. We frankly believe that day is coming. ”

Bridges fought against worker exploitation and union corruption. In the ’20s and ’30s, the notorious “shapeup” system required longshoremen to report to the docks before dawn. During this daily hiring ordeal, bosses would weed out “radicals” and “troublemakers.” Corrupt hiring bosses would often get kickbacks from longshoremen’s wages. Bridges’ leadership put an end to the shape-up system and instituted true democracy among the rank and file.

“What I remember most about Harry is his consummate skill at communicating an idea to the membership and making them believe that it was their idea in the first place. He always took a proposal to the rank and file and did not try to stuff it down their throats,” recalls attorney Bob Duggan, ’54, ’61 , who worked as a longshoreman while attending college and is a past UW Alumni Association president.

Throughout his career, Bridges was a leader for social change and championed causes such as civil rights, equality for women, Social Security and national health care—years before they became an accepted norm. “What he told his people is that the employer will try to divide and conquer us on a racial basis, and we cannot let that happen,” Duggan says.

Seattle Times Columnist Emmett Watson said of Bridges, “Long before it was fashionable, Harry’s ILWU employed blacks and women. He instituted open enrollment procedures, he drew a modest salary and he was dollar-honest. When he retired some years ago, Harry Bridges left his followers with some of the highest wages and benefits ever enjoyed by American workers.”

Bridges never denied his ideas were “radical,” but he fought against charges that he was a Communist. In 1938 FDR’s labor secretary, Frances Perkins, issued a deportation warrant, but it was overturned when the dean of the Harvard Law School ruled there was no evidence of “undemocratic or unconstitutional” behavior.

In 1940 the House of Representatives voted 380 to 42 for Bridges’ deportation, but the Supreme Court invalidated the order. In 1949 he was indicted for perjury for denying Communist Party membership at an earlier naturalization hearing. Though convicted and sentenced to five years in 1950, he only spent three weeks in jail before being freed on appeal. Eventually the Supreme Court overturned the conviction. Justice Frank Murphy wrote in his concurring opinion, “Seldom, if ever, in the history of this nation has there been such a concentrated and relentless crusade to deport an individual because he dared to exercise the freedom that belongs to him as a human being, and is guaranteed to him under the Constitution.”

By 1970 Bridges was a respected labor leader and became a member of the San Francisco Port Commission, where he served for 12 years. He retired as head of the ILWU in 1977 and died in 1990.

The $1 million Harry Bridges Endowed Chair in Labor Studies is part of the Center for Labor Studies in the College of Arts and Sciences.

The fund that endowed the Bridges chair was raised in just two years, largely from contributions of $500 or less from rank-and-file union members and retirees. More than 990 individual donors and 90 organizations gave to the fund, as did members of Bridges’ management adversary, the Pacific Maritime Association. The effort, says Duggan, received an extra boost when UW President William P. Gerberding donated $1,000 while attending the 1991 ILWU convention to accept the first gifts to the chair.

Pictured at top: Boeing workers strike in 1989 (Seattle Times photo).