Brandon Roy still refers to the play, only half-jokingly, as “the highlight of my career.” It was the 2000 Washington State Basketball Tournament, and he had come off the bench for Garfield High School in its quarter-final round game against Mountlake Terrace. A gawky, untested sophomore, he quickly found himself face-to-face with the most notorious shot-blocker in the state—Seamus Boxley, a 6-foot, 7-inch senior bound for an NCAA Division-I team. Roy sized up his opponent, drove baseline, leapt into the air and dunked on Boxley with both hands.

“I couldn’t even sleep that night, I was so happy about that,” Roy recalls. “I think I only had, like, four points, but that dunk felt like 20.”

It may surprise fans of the mature Brandon Roy—who favors a slow-paced offense and likes to wear down flashier opponents with grit, finesse and grace under pressure—to learn that he was once known mainly for his 42-inch vertical leap. “Brandon could jump higher than any other person I’ve ever seen on the floor,” says Cole Allen, Roy’s best friend since high school. He remembers the day after the 2000 NBA Slam Dunk Contest. “Brandon was in the gym during lunchtime, duplicating those dunks in front of the whole school.”

Roy rises above Arizona’s Mustafa Shakur during the 2004 Pac-10 tournament. Photo by Mark J. Terrill, Associated Press.

In the years since, Roy has battled knee and ankle injuries, 7-foot centers, and his share of lousy luck, and has learned that some obstacles simply can’t be jumped over. But he has also proven extraordinarily skillful at finding other paths to the goal—whether in basketball, in the classroom, or in the world beyond. Indeed, if one sports cliché—“he can jump out of the gym”—no longer applies to Roy, another seems more appropriate every day: when it comes to potential, the man has no ceiling.

That’s a good thing, because at this point expectations are through the roof. As co-captain of the Portland Trail Blazers and reigning NBA Rookie of the Year, Roy is expected to put up big numbers every night, make everyone around him better, and help rehabilitate a troubled franchise.

It would seem like too much to ask of a second-year combo guard—if Roy weren’t doing it. With his indomitable game, he is leading the Blazers out of the cellar and into the playoffs. With his charisma and, possibly, clean-cut image, he is helping a city jaded by years of the “Jail Blazers” care about its only major-league sports team again. And with his work in the community, including service as a spokesperson for the UW’s Students First scholarship program, he is using his newfound celebrity to make something even more important than big money—a big difference.

***

Like Bob Hope, who had six brothers and famously joked that he learned to dance “waiting for the bathroom,” Brandon Roy found out about sharing at an early age, growing up in a small West Seattle duplex with five other family members. His father, Tony Roy, drove a Metro bus for a living; his mother, Gina, worked in a grade school cafeteria. There was an abundance of love in the Roy home, but not much elbow room, and Brandon has attributed the unselfishness for which he’s known on the court to his upbringing in a family that was close in both senses. “I always felt I had to put my own selfish things aside,” he told the Seattle Times, “so my brother could have more, my sister could have more.”

For many years, that included yielding the spotlight. As an adolescent, Brandon Roy was known mainly as Ed Roy’s little brother. Two years Brandon’s senior and a standout in both football and basketball, Ed Roy cast a long shadow at Garfield. Brandon, meanwhile, was undersized and quiet. He didn’t start to see serious playing time in varsity games until the second half of his sophomore year, and didn’t really catch the eye of Coach Wayne Floyd until the day he dunked on Seamus Boxley.

“That really kind of raised our eyebrows,” recalls Floyd, now principal of Seattle’s Cleveland High School. “It’s one of those things where you don’t even jump out of your seat. You just kind of sit there thinking, ‘Did I just see that?’ I looked at our junior varsity coach, and I’m like, ‘Um, you’ve been hiding and hoarding this guy all year, man?’ ”

Roy, for his part, says he always knew he had a special talent, and that developing it—rather than coasting on it or boasting about it—was his top priority. While the other kids at the Delridge Community Center were rehearsing buzzer-beaters, he was working on his dribbling and free throws. “I always felt like I was going to make it to the NBA,” he says. “And I was serious about it. I would work at my game all the time. And I would always ask people, ‘What do I need to work on? What do I need to get better?’ I understood criticism, and I accepted it. Because I knew it would only help me get to the level that I wanted to be at.”

“I understood criticism, and I accepted it. Because I knew it would only help me get to the level that I wanted to be at.”

Brandon Roy

By his junior year at Garfield, Roy says, he felt “ready to take over,” and he did, scoring nearly 19 points a game and leading the Bulldogs to a 27–2 record. After an even stronger senior season, he decided to enter his name in the NBA draft. But a workout with—of all teams—the Blazers convinced him that he wasn’t ready to compete at that level, so he withdrew and accepted a basketball scholarship from the UW.

In doing so, Roy prepared to join fellow Garfield grads Will Conroy and Anthony Washington and Rainier Beach product Nate Robinson in a mass migration up 23rd Avenue to Montlake. Increasingly, rather than departing for the nation’s elite basketball programs, local legends were choosing to stay home and help build one at the UW. “It’s hard for me to understand why people leave the state so much,” Roy told The Daily at the time. “Why not make the place where you grew up a good team?”

Before he could get started, though, there was one more big number he’d need to put up: a qualifying SAT score. Roy suffers from a learning disability that makes timed tests extraordinarily difficult, and his first attempt at the SAT fell short. Working with tutors, Roy retook the test late in his senior year, and this time his score shot up so dramatically that officials flagged the result as suspicious. Just as Roy was preparing to start fall classes at the UW, word arrived that the NCAA had declared him ineligible. Suddenly, a young man with his sights set on a multi-million-dollar NBA contract found himself hosing out shipping containers at the Port of Seattle for $11 an hour. “I was a nobody,” he told the Seattle Times a couple of years ago. “I was that guy they said, ‘What happened to Brandon Roy? He’s another guy who failed.’ ”

Those months were especially demoralizing for Roy, he says, because he’d just seen his brother go through the same thing. Coming out of Garfield, Ed Roy had scholarship offers from Division I schools in both football and basketball. But he also had a learning disability—and unlike Brandon’s, it had gone undiagnosed until his senior year. Academics, for Ed, proved too big a barrier, and he hung up his basketball shoes at the age of 20. Brandon decided he wasn’t going to let history repeat itself. He’d work at the shipping-container plant every morning, then come home and prep for the test with a personal tutor. “Just him and the tutor every day,” Cole Allen recalls. “I’d come by to see if he wanted to do this or that, and I know he wanted to. But he was just thinking ahead. And it paid off.”

After the NCAA flagged the SAT scores, Roy’s parents encouraged him to “make [the NCAA] flag you again,” and sure enough, his third SAT score proved to be his highest. On January 16, 2003—the day of the Huskies’ home game against Cal—Roy sat in the UW players’ lounge nervously awaiting word from Coach Lorenzo Romar on the NCAA’s verdict. When the coach finally summoned Roy to his office he seemed distracted, and Roy feared the worst. Then Romar spoke: “I’m trying to figure out if we can get you a uniform for tonight.”

***

Roy spent much of his collegiate career hobbled by injuries and upstaged by more dynamic players like Nate Robinson, the spring-loaded guard who would later take his airshow to Madison Square Garden for the New York Knicks. In his first three years, Roy never averaged more than 13 points a game.

But if you ask coach Romar when he first realized Roy was the best player on the team, he’ll hold up a massive index finger: “Day one.”

Photo by Scott Cohen

“When he joined us in January of his freshman year, we took him up to the gym and he learned our offense in 45 minutes,” Romar recalls. “High basketball IQ. He can handle the ball. Athletic. From day one we knew.”

Roy could do it all—score, rebound, distribute, defend. But the hallmarks of his game were anticipation, unselfishness, hustle and heart—the qualities collectively known as “the intangibles.” “My dad used to tell me, ‘If you want to stay on the floor and play, you’ve got to be able to do the intangibles,’” Roy says. “And I’ve watched guys who can score great in high school but get to college and struggle. And I always said, ‘Well, if I can develop every aspect of my game, coach is going to have to play me.’ ”

Of course there were some tangible signs of Roy’s promise, too, for those willing to look closely. Season after season, he would hit more than half of his shots. His junior year, he nailed 56.5 percent of them—the second-best percentage in the Pac-10, and a level of efficiency unheard of in a guard.

Roy thought seriously about jumping to the NBA after three years, but decided “there was still more I needed to show” and stuck around for one more campaign. The result may be as close to a perfect season as a Husky has ever had. Roy was a First-Team All-American and a runaway winner of the Pac-10 Player of the Year honor, leading the conference in scoring and finishing among the top 10 in a shocking 10 of 13 statistical categories. In the NCAA tournament, he propelled the Huskies to their second straight Sweet 16 appearance, schooling a higher-seeded Illinois team along the way in a classic contest. Roy drew three defenders the whole game and still managed to tally 21 points.

“After the game,” Romar remembers, “their coaches, one by one, came up to me and said, ‘Lorenzo, we watched the film. We watched him play. We knew he was really good, and we prepared to stop him. But we didn’t know he was that good—that you can’t stop him.’”

***

Roy was flying high—and yet he still seemed, somehow, to be flying under the radar. His name didn’t really come up in conversations about the national Player of the Year awards, which tended to center on big-time scorers Adam Morrison of Gonzaga and J.J. Redick of Duke. Even the unqualified praise Roy received from NBA big shots had a tepid quality to it. They seemed less interested in his ability than his stability.

After a workout with the Charlotte Bobcats, Roy wondered whether he was being groomed for some sort of junior-executive position. “They said they were excited about me, because I was a good person and that I was a nice guy,” he told the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. “I was laughing and I asked them, ‘But what about my workout?’” Ultimately, Roy was selected sixth in a draft that everyone seemed to agree was underwhelming. Few people, it’s safe to say, saw his rookie season coming.

Roy put the league on notice with his first NBA game—a homecoming victory against the Seattle SuperSonics in which he scored 20 points. Despite missing nearly a quarter of the season with an ankle injury, Roy held down averages of 16.8 points and 4 assists a game, leading all rookies in both categories. He also established himself as the Blazers’ go-to player in clutch situations. Almost immediately, he became the prohibitive favorite for Rookie of the Year. (In the press, the fact that his last name was an acronym for “Rookie of the Year” only added to the sense of inevitability.) On May 7, 2007, the NBA announced that he had received 127 of 128 first-place votes.

In his senior year, Roy led the Pac-10 conference in a shocking 10 of 13 statistical categories. Photo by Brian Spurlock.

“I’m not a big I-told-you-so guy,” Romar says, “but it definitely confirmed what we knew over here. … In speaking to NBA people when he was a senior, I remember specifically telling someone that they needed to take a look at drafting Brandon. And the comment was, ‘We need veterans.’ And I said, ‘By January he will be a veteran.’”

Now in his second season, Roy leads the Blazers in points, assists and steals, and has taken part in his first All-Star Game. After a rough start, the team went on a winning binge and vaulted from 5-and-12 into playoff contention. Along the way, Roy performed a bit of aerial hocus-pocus that may finally have displaced the dunk on Seamus Boxley as his career highlight. Starting at the top of the key, he shook off one Toronto Raptor with a crossover dribble, blew by another and rose for a layup, only to encounter the flying 6-foot,10-inch frame of All-Star forward Chris Bosh. In a move reminiscent of Michael Jordan, Roy switched the ball in midair from his right hand to his left and flipped in a feather-touch layup as Bosh sailed irrelevantly out of the picture. It wasn’t a dunk, but it did end up as the “Amazing Play of the Month” on NBA.com. Not surprisingly, the Trail Blazers Campus Store reports that Roy’s jersey is their number-one seller.

Best of all, Roy is the face of the new Blazers—modest, likeable, a winner on and off the court. Gone are the days when the team’s marquee players seemed to turn up on the police blotter as often as they did on “Plays of the Week.” “I’m staying humble,” Roy has said. “There will be no tattoos. I don’t want things like gold chains. I’ve got an image I want to keep.”

He has been highly visible in the community, volunteering for Big Brothers Big Sisters, serving as a crossing guard for a local elementary school and laying the groundwork for the Brandon Roy Foundation, which will help kids with learning disabilities. Roy calls it a tribute to his brother Ed. “To know how much it would’ve meant to him just to set foot on a college campus—it makes me sad, I think, more than him,” Roy says. “He’s grown up from it, but it’s like I can’t let it go. Because I feel like maybe he was cheated a little bit. And I don’t want to let that happen to any other kids.”

Roy has also made public his determination to finish his UW degree in American ethnic studies—not so much for his own sake as to set the right example for Brandon Jr., a son born last year to Roy and his longtime girlfriend Tiana Bardwell. He’s just a few credits shy, and hopes to pick them up during the off-season. “That’s extremely high on his list of priorities,” Allen says. “Brandon really looks at things on a grand scale. His son might not want to grow up and play basketball, and he’s got to know that there are other ways to succeed.”

And so the secret is finally out, and Roy, for the first time in his life, does not have the option of exceeding everyone’s expectations. They’re too high. But Roy says he has no problem with that. After all, he has been part of one basketball program’s renaissance already—the UW’s. And as for being a role model, “I welcome that side just as much as the basketball side,” he says. “Because, you know, in college, Coach Romar not only demanded that we were good on the court. He demanded the same thing off the court. So when I was drafted by Portland and I heard all the bad talk about the Trail Blazers, I wasn’t nervous at all. Because I knew that if I came here, I wouldn’t have to change the person I was off the court. I’d just have to be myself.”

One more assist from Brandon Roy

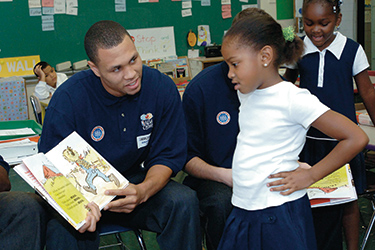

When he’s not schooling the visitors, Roy is visiting the schools. NBAE/Getty Images.

Brandon Roy paid for college with a basketball scholarship. Now that he’s in the NBA, he’s happily footing the tuition bills for both his sister, Jaamela, and his best friend, Cole Allen. But he realizes that not everybody has the option of being a basketball star—or a basketball star’s best friend. That’s why he decided to step forward as a spokesperson for Students First, the UW’s new scholarship program for needy students.

“Being raised in the inner city, if I didn’t get a basketball scholarship, I probably wouldn’t have been able to go to a Division-I school,” Roy says. “Students First isn’t a basketball scholarship, but it is a program to help underprivileged kids get into college. And I was thinking that if I could put my voice out there for it, people might say, ‘Hey, Brandon Roy’s a part of it and it doesn’t even have to do with basketball. Maybe it’s a good thing.’”

Students First provides scholarships to undergraduate, graduate and professional students on the basis of need. It’s a matching initiative—the UW will donate 50 cents on the dollar for every contribution to Students First, large or small. Gifts of $100,000 or more become named endowments and receive matching funds on 50 percent of the principal. Smaller donations are pooled together in the Students First Matching Challenge Fund, half of which will also be matched by the University. The program was announced in late 2006 and has already raised more than $65 million in gifts, pledges and matching money.

Roy’s smiling face now appears in print and television advertisements promoting the program. And he has been making public appearances in his new role. He’s not a man with a lot of free afternoons and evenings, but Roy says he’ll always have time for the UW—and for a program as deserving as Students First. “I just jumped at the opportunity to be a spokesperson for it.”

To learn more about Students First, visit uwfoundation.org.