Scientists are by their nature inquisitive, but Ellen Vitetta says that in her 30-plus years of training young microbiologists she has never met anyone who asked as many questions as Linda Buck, '75.

“I don’t just mean questions about her work,” says Vitetta, who was Buck’s mentor at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in the mid-’70s. “I mean, ‘Why is the sky blue? Why is that flower pink?’—that kind of thing.” At a Christmas party that featured skits and spoofs on department personalities, the woman who portrayed Buck simply wandered the stage asking questions.

Along with her curiosity, Buck is remembered at UT for her keen, original mind and her work ethic. So when she was named co-winner of the 2004 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for her groundbreaking investigations into the human sense of smell, no one was especially surprised. “We had a press conference down here,” Vitetta recalls, “and everyone was laughing and saying, ‘I knew she’d eventually ask the right question.”‘

Vitetta, who is now professor and director of the Cancer Immunobiology Center at UT Southwestern, may have been the least surprised of all. She had stayed in close touch with Buck through the years, and had seen the breakthrough paper before it was even published—the 1991 paper in which Buck and Richard Axel, her postdoctoral advisor at Columbia University, first identified the family of genes that allows humans to detect and distinguish smells. “I immediately recognized it was Nobel material,” Vitetta says. “It was a paradigmchanging paper. I knew as well as you can know without any evidence that Linda and Richard would get the prize. It was just a question of when.”

Now Buck, a member in the division of basic sciences at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and an affiliate professor of physiology and biophysics at the UW, has another prize to put on her increasingly crowded mantel. The University of Washington and the UW Alumni Association have named her the 2006 Alumna Summa Laude Dignata—the alumna of the year. It’s the highest honor the University confers upon its graduates, and Buck is its 66th recipient.

Buck comes by her curiosity naturally. Her father was an electrical engineer who liked to invent things in the basement of the family’s Green Lake home. Her mother was a crossword-puzzle buff. (“I’ve never been that interested in crosswords,” says Buck, “but I think I got some of that same joy in puzzle-solving.”) Both parents encouraged Buck and her two sisters to pursue their passions and to question everything, including their own assumptions. Other children buried their pet hamsters in the backyard. Buck, curious about decomposition, exhumed hers.

“I did feel strongly that I should try to help people, and for a while I thought I might be a psychotherapist.”

Linda Buck

But she never suspected she’d be a scientist. When a teacher at Roosevelt High School wrote in her yearbook that she might make a fine biologist one day, Buck thought, “That’s really strange.”

“I thought I wanted to help people,” she says. ”Actually, I’m not sure what I thought—I was a junior in high school. But I did feel strongly that I should try to help people, and for a while I thought I might be a psychotherapist.”

Buck threw herself into the study of psychology when she came to the UW in 1965. She even approached Walt Makous, one of her first professors, and asked if there was any research she could get involved in. “I was unfunded at the time—I was just a beginning assistant professor,” says Makous, who left the UW in 1979 to direct the Center for Visual Science at the University of Rochester. “But a colleague of mine had left an apparatus fallow for two weeks while she went on Christmas vacation. So I used it for an experiment, and Linda helped me with it. She was one of the two subjects; I was the other one.” Their psychophysical study, which concerned light passing through different pathways in the eye and how it stimulated the visual system, resulted in a published article.

Buck was always an enthusiastic student. “I loved going to school at the UW,” she says. “I loved my courses.” But by the time she completed the requirements for her degree in psychology, she had decided it wasn’t the field for her. So she delayed graduation and took some time off. When she returned to the University, she discovered immunology—the subject from which she “never looked back.” After graduating in 1975 with degrees in both psychology and microbiology, she made her way to the doctoral program at UT, which was emerging as a hub of immunology research. It was there, Buck says, under the exacting gaze of Vitetta, that she really came into her own as a scientist.

The next step was postdoctoral work at Columbia, where her interest in studying biological systems at the molecular level eventually led her to the lab of Richard Axel. For a while she assisted in his research on the nervous system of a sea snail. But in 1985 she read a paper that got her thinking, for the first time, about what a sophisticated piece of equipment the nose is. This, she realized, was the “monumental puzzle ” she’d been looking for. “How could humans and other mammals detect 10,000 or more odorous chemicals, and how could nearly identical chemicals generate different odor perceptions?” Buck wrote in an autobiographical essay for the Nobel Web site. “In my mind, this was … an unparalleled diversity problem.”

For years, scientists had posited the existence of odorant receptors—proteins that pick up smell molecules and excite the olfactory neurons in the back of the nose. But everyone who had tried to find them had hit a brick wall. Within the field, the cause had come to seem so hopeless that when Buck was ready to leave Columbia, she found she had nowhere to go. “I actually applied for a job, saying that I was going to try to find these odorant receptors,” she says. “I didn’t even get an interview.”

So she stayed in Axel’s lab, knowing she would have support and a certain amount of freedom. Axel, she writes, “was an unusual mentor in that he gave people … extensive independence in charting their own course once they had established themselves.”

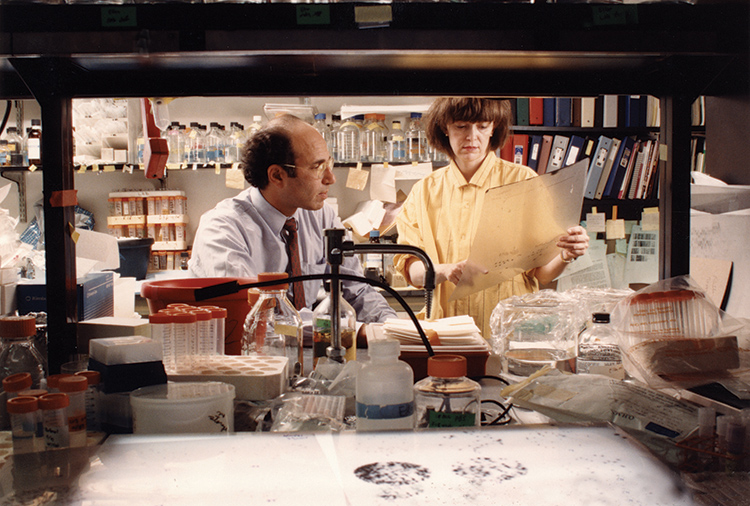

Columbia University Professor Richard Axel consults with Linda Buck in his laboratory during their collaboration in the 1990s. The two shared the 2004 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine. Photo by Kay Chernush, © Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Because the odorant receptors had eluded everyone who’d gone looking for them, Buck and Axel decided to try a different tack—looking, instead, for the genes that encode them. At first they found nothing. But then Buck came up with what Axel has called “an extremely clever twist.” She radically narrowed the field of possible genes by making three educated assumptions about them: that they’re a multigene family; that they’re expressed only in the olfactory epithelium; and that the proteins they encode resemble rhodopsin (the receptor protein in the eye). “Had we employed only one of these criteria, we would have had to sort through thousands more genes,” Axel told a reporter. “This saved us years of drudgery.”

Still, the breakthrough didn’t come overnight. Buck estimates she worked 15 hours a day for two and a half years on the project. Makous remembers visiting her in New York at the time. “I came in at around dinnertime,” he says, “but she had to work in the lab until around 10 o’clock or so before we could go out to eat.”

When the results finally began rolling in, Buck’s first feeling was neither pride nor relief, but awe. “Looking at the first sequences of odorant receptors … ” she writes, “I was moved by Nature’s marvelous invention.” Buck always capitalizes

‘Nature’ in her writing—a reverence that’s audible when she speaks, too. “Nature is quite elegant in its design,” she says. “It’s a wonderful puzzle.”

After the first findings were published, Buck no longer had trouble getting job interviews. She moved on to a professorship at Harvard, pursuing research that built on the odorant receptor work. By answering an old question, she and Axel had put all sorts of new ones in play. They had shown, for example, that the family of odorant receptor proteins was indeed large—about 1,000 in all. But that’s nothing compared to the number of odors out there. Why is it that we mammals can sense so many smells using so few smell sensors? For the same reason we can form close to a million English words using only 26 letters, Buck has proven—we use them in combination. The Nobel committee recognized Buck and Axel not only for their breakthrough, but for a decade’s worth of subsequent discoveries.

“I realized, when I got the phone call, that I would have a new set of responsibilities.”

Linda Buck

In 2002, Buck accepted an appointment from Fred Hutchinson and returned to Seattle. A year later, she joined the UW faculty as an affiliate professor. Mark Groudine, who recruited her to “the Hutch,” says he considers it a huge coup—even with the hometown advantage. Buck was giving up a full professorship at Harvard to come to an institution where there’s no tenure, and where every researcher gets the same amount of lab space regardless of reputation. “I mean, she could’ve had, probably, half a Boor somewhere at this point,” he says. But the absence of professional hierarchies was precisely what appealed to Buck. “No one has an empire here,” says Groudine. “Everyone is treated equally. And so there’s just a lot of interaction, a lot of collegiality, because no one’s looking over their shoulder worrying that someone else is getting more than they are. I think Linda really liked that model.”

Everyone who speaks of Buck speaks of her collegiality. Groudine sees it as something almost genetic—a byproduct of her innate curiosity. “She’s one of these people who really tries to understand your work,” he says. “Forget about the Nobel and the science,” says Vitetta. “She’s one of the most decent people you’ll ever want to meet. She’s never had an agenda of hurting anybody or stepping on anybody, and to me that’s every bit as important as what she accomplished—that she didn’t do it at anybody else’s expense.”

In early October 2004, the Hutch was looking for a couple of new faculty members and Buck was heading up the searches, which had drawn resumes from all over the world. So when a man with a Swedish accent called Groudine at 2 a.m. and said he was trying to reach Linda Buck, it seemed pretty clear what was up. Groudine asked the caller if he had any idea what time it was in the western United States, and assured him that this was no way to get a job at the Hutch. The man then explained that he was calling on behalf of the Nobel Prize committee. Groudine corrected himself: “Well, that is a good way to get a job here.”

Linda Buck returned to Seattle in 2002. Photo courtesy of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

A few moments later, Buck received a similarly disorienting call. The next several weeks were a whirlwind of press conferences, interviews and champagne receptions, culminating in a trip to Stockholm for the prize ceremony in December. Buck is a rather private person, but she embraced this new public role because it gave her an opportunity to make the case for the kind of work she does. “I realized, when I got the phone call, that I would have a new set of responsibilities,” she says, “having to do with communication with the public about the importance of basic science.”

That importance isn’t self-evident to everyone, Buck says. When speaking about her work, she’s sometimes surprised to find herself on the defensive. “Even some science journalists have asked me what diseases this olfaction research might cure,” she says. “I think a lot of people don’t realize that basic science generates the sort of fundamental information that’s required to understand things like disease processes and disease prevention. There’s also a lot of cross-talk between fields, where research into the sense of taste might for some unexpected reason prove to be crucial to understanding, say, cancer.”

Vitetta accompanied Buck to Stockholm, and marveled at how well her former student handled all the attention—the camera flashes, the relentless pressure to keep smiling. “I remember standing beside Linda when she was in the reception line,” says Vitetta. “She and Richard were there shaking about six gazillion hands, and Linda turned to me and said, ‘My pinky’s going numb.’ So I went and got her a glass of wine.”

Although they’re quite close in age, Vitetta says her feelings toward Buck are, perhaps inevitably, somewhat maternal, and that the news of the Nobel was a kind of turning point in her own life. “For most scientists, our currency is our own ego,” she says. “We thrive on people reading our papers and quoting them and doing new experiments based on them. And suddenly, here I was, thriving on the success of someone I had helped train. And it was a different kind of success for me. It was the kind you feel when your child grows up to be healthy. And I don’t know that I could’ve felt that 20 years ago, because I was too busy feeling about my own success.”

Interestingly, Buck says something quite similar about winning the prize. For all the personal and professional satisfaction it brought her, the most intense pleasure she felt was vicarious.

“I kept hearing from family, friends, even old acquaintances,” she says, “calling me up and telling me they’d heard the news and how happy it had made them for an entire day. And that was the best thing about it—that it made so many people I care about so happy.”

Ann Aagaard

The last person who expected to hear news of Linda Buck’s Nobel Prize may also have been the first person to foresee it. Ann Aagaard was the teacher at Seattle’s Roosevelt High School who wrote, “You may make a fine biologist one day,” in Buck’s 1964 yearbook. But she has no memory of that inscription—or, indeed, of that student. So when a representative of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center called in October 2004 to tell her that Linda Buck had won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, and had mentioned her junior-year biology teacher as an early influence, Aagaard was speechless.

“It came absolutely out of the blue,” she says. “I thought it was just amazing.”

A few months later, she and her former student reunited for the first time in 41 years at a reception in Buck’s honor. Seeing her there, Aagaard did recognize Buck—and Buck recognized Aagaard with some grateful words. Afterwards, a number of people came up and congratulated Aagaard, including a total stranger who gave her a big hug and said, ‘You must have been some biology teacher.’ ”

“I have to tell you,” she says, “I was kind of overwhelmed by the whole situation.”

Aagaard taught at Roosevelt for only that one year. She suspects she would remember her students more vividly if she had known them longer. What she does remember is the biology classroom she was given, which, to a first-time teacher, had an almost hallowed feel to it.

“Eons of teachers had left behind all these collections of insects and marine life,” she says. ‘”All these wonderful things that you don’t really see in biology labs anymore—you would pull out these old drawers and there would be seashells, and things in formaldehyde. It was thrilling.

“And I had just graduated from Oberlin,” she says. “Watson and Crick had just started publishing the first really exciting information on DNA. It was just a wonderful time and a wonderful place to be a biology teacher, and I was very enthusiastic about what I was doing. And I think that somehow that came across to my students, to Linda.”

Aagaard spent the following year at Cleveland High School, then left to raise her family and never returned to teaching. (Her husband, Knut Aagaard, ’64, ’66. is a longtime professor of oceanography at the UW.) The brevity of her career, she says, makes that phone call back in October seem all the more miraculous.

“As my husband says, ‘Wouldn’t it be wonderful if everybody had a Nobel Prize-winner for every two years they taught?’”

At top: Linda Buck, ’75, center, acknowledges the applause of fellow laureates Richard Axel, left, and Finn Kydland, right, during the Dec. 10, 2004, Nobel Prize ceremony in Stockholm. AP Photo by Henrik Montgomery.