A nursing leader’s living legacy A nursing leader’s living legacy A nursing leader’s living legacy

One of Seattle’s few Black nurses in the 1940s, Rachel Suggs Pitts helped create a network of support for her colleagues and nursing students.

By Luna Reyna | Viewpoint Magazine

Rachel Suggs Pitts, one of Seattle’s few Black nurses in the 1940s, played a key role in UW virus research, worked as a public health nurse and provided decades of health service. But perhaps her most profound contribution was to future generations of Black nurses.

Pitts died in April, only a few months shy of her 100th birthday. She was the last remaining founder of the Mary Mahoney Professional Nurses Organization (MMPNO). The club for Black nurses started in 1949 and today provides mentorship, financial aid and scholarships to students of African heritage pursuing careers in nursing. Through the organization and beyond, Pitts nurtured generations of young Black nurses. And they have gone on to advance public health both locally and nationally.

Rachel Suggs Pitts “is a model of what it means to be engaged in your profession up until the end of your life,” says Frankie Manning, a former UW faculty member and longtime member of the MMPNO. “She was always present because she wanted the young nurses to understand how important it was for them to go to school.”

Rachel Suggs was born in Lakeland, Georgia, the fourth of five children. She grew up in a close-knit Black community, and many of her earliest memories were set at the Baptist church where her family worshiped and she attended school until the eighth grade.

When she was 5, her father died. By age 11, she was working for a registered nurse—a white woman—who needed help caring for her sick husband. Pitts also knew the midwife who delivered her community’s babies. According to several sources, the combination of these experiences and her faith made her want to become a nurse.

“How important it is just to go after a job in a very white city, then to get that job, and to be able to navigate it. Hers is a story of courage.”

Marla Salmon, UW professor

After high school, she worked almost two years to save for nursing school. She finished her clinical affiliation at Freedman’s Hospital in Washington, D.C., with experience in psychiatry and communicable diseases, but there she could only work with Black patients.

During this time, Pitts started a family. Her husband was in the Navy, and she hoped to move to Seattle to await his return from the war. She found a job at Seattle’s Harborview Hospital where she was placed in the communicable disease unit with the hospital’s other Black nurses.

In 1949, Pitts and 11 other nurses were invited to a meeting at fellow nurse Anne Foy Baker’s home. That night they formed the Mary Mahoney Professional Nurses Club, named for the first professionally trained Black nurse in the country. “Their early efforts involved bake sales, car washes and social events to try to raise money,” says Manning. The organization would pay for new members to go to the beauty salon, be treated to dinner and be taken to church. Later, the money raised was directed to scholarships. From the beginning, the group focused on creating a variety of support systems for its members.

One element of the support became the MMPNO mentorship program. “They were pretty diligent and very intentional in terms of providing mentors to us,” says Shavonne Reynolds, MMPNO member, registered nurse and a current doctor of nursing practice student at UW. Her mentor is Manning. “She is just a wealth of information. I can call her just to vent and to get guidance on my professional decisions and school decisions,” she says. “Having someone who understands what it’s like to be a Black nurse, and specifically a Black nurse in Seattle, and to have that trust-building aspect of it in that shared life experience, has been tremendous.”

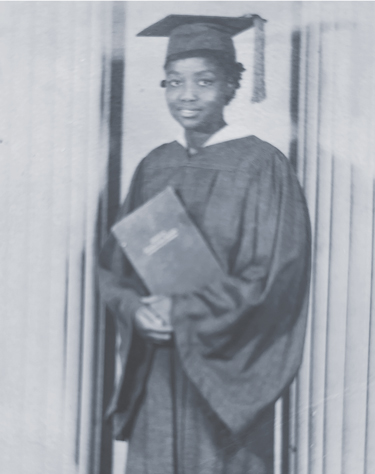

After graduating from high school, Rachel Suggs Pitts saved up for nearly two years to attend nursing school. (Photos courtesy of the Suggs Pitts family)

In 1956, Pitts graduated with a bachelor’s degree from the UW School of Nursing and began work as a public health nurse. She also brought her expertise to a sudden infant death syndrome project, a sickle cell screening service, a genetic counseling program, and a maternal and child health group.

“From a public health perspective, for her to have been a Black public health nurse at the time that she was, in a city that was pretty fundamentally segregated, was really amazing and it was powerful,” says Marla Salmon, a professor of nursing and global health at the UW. “How important it is just to go after a job in a very white city, then to get that job, and to be able to navigate it. Hers is a story of courage.”

Because of her expertise in infectious diseases, Pitts was invited to work on a UW Department of Epidemiology and International Health on a virus watch study. Unfortunately, she was not credited for her work. “It has not been uncommon for nurses to really be able to do a large part of the research legwork and have lots of influence on the data collection and how it’s done, but no credit is given,” Manning explains.

When Vivian Lee, ’55, met Pitts, Lee was struggling to get into the UW Nursing program. “She was the one who encouraged me,” Lee says. “I was interviewed quite a few times more than most students. They were very skeptical about African American students being able to achieve as highly as [the white] students.” While the situation has improved, there are still disparities, both in the nursing profession and in the health of many communities of color, which is where Lee has focused much of her career. Pitts was passionate about addressing health disparities, and she instilled this same passion in generations of MMPNO nurses, says Lee. “She said to us, ‘Remember our community and the disparity in health care that still exists in the many communities of color.’”

Pitts was someone who used her own achievements to uplift others, a focus at the core of the MMPNO mission. “She understood that working with others in community for the goals of equity and social justice was far more powerful than just one person doing it,” Salmon says.

Pitts retired from professional nursing in 1985 but continued to provide health services to family, members of her church and those who asked for help. To memorialize Pitts’ legacy, Salmon created an endowed scholarship in her name. “I have huge admiration for her and was really happy to have the opportunity to do something to celebrate her life,” Salmon says. “I know there’s a lot of discussion now about diversity, equity and inclusion, but we are at the beginning of the journey, we’re not at the end.”