It's enough to make you sick—sinks ripped off restroom walls, road signs mowed down by some hooligan's pickup, spray-painted graffiti on roadside markers—and all of it in the midst of our nation's crown jewels, our national parks.

But University of Washington researchers say that national park vandals are not just beer-drinking teenagers. Culprits also include the average family of four with their cameras and picnic lunches.

Minor rule-breakers—who might pocket petrified wood, stray from established trails or feed peanuts to ground squirrels—are causing much more damage than intentional vandalism, as much as $100 million, says Darryll Johnson, a National Parks Service researcher based at the UW College of Forest Resources.

Park managers estimate that it would take $100 million to fix repairable damages and clean up in the wake of careless visitor behavior, according to a new park service report. Johnson, social science program leader of the Cooperative Park Studies Unit at the DW; Mark Vande Kamp, a UW graduate student; and Tommy Swearingen, with the University of South Alabama, conducted this nationwide survey. It’s the first-ever tally of damage inflicted by visitors at hundreds of National Park Service sites—which include forested areas, seashores and monuments.

Respondents gave estimates only for repairable items. The $100 million does not include the cost of features that can’t be repaired, because either no technology exists or the resource is simply gone—destroyed. These include:

There is a difference between minor rule violations and hard-core theft and vandalism. For example, Native American archaeological sites are often “potted”—a term used for a site denuded of artifacts (often pots) by collectors or profiteers. That’s different from a site that loses its appeal after hundreds of tourists each carry off “just one or two” arrowheads as mementos. Other examples of visitor misbehavior include taking horses or dogs where they don’t belong, feeding Twinkies to the wildlife or catching more fish than is allowed.

Using effective signs instead of lame ones may be the difference between acceptable and unacceptable resource loss.

Park visitor behavior becomes criminal behavior when it comes to killing protected wildlife. Those who traffic in the feathers and tails of bald eagles, for example, are like the thieves who strip archaeological sites of ancient pots. One of the more unusual wildlife cases happened recently at Mount Rainier National Park, where rangers came upon a family dining on roasted marmot. Most visitors would probably not want to sup on this furry cousin to the woodchuck. In this case, the diners were recent immigrants ignorant of rules that forbid clubbing and cooking wildlife.

Getting everyone to know and understand the rules is a prime objective in the parks. Practical ways to foster better behavior were studied in 1985 at Mount Rainier, one of the first projects of its kind in the national parks.

Rainier visitors often wander off official trails and since the 1950s the park has been replanting trampled areas, explains Rainier Botanist Gina Rochefort. But webs of “social trails” have continued to spread over the fragile alpine landscape. Rochefort, on leave while earning her doctorate in forest resources at the UW, says the 1985 study tried to prevent off-trail wandering in Paradise Meadows, a 900-acre area with fragile soils and glorious summer wild flowers.

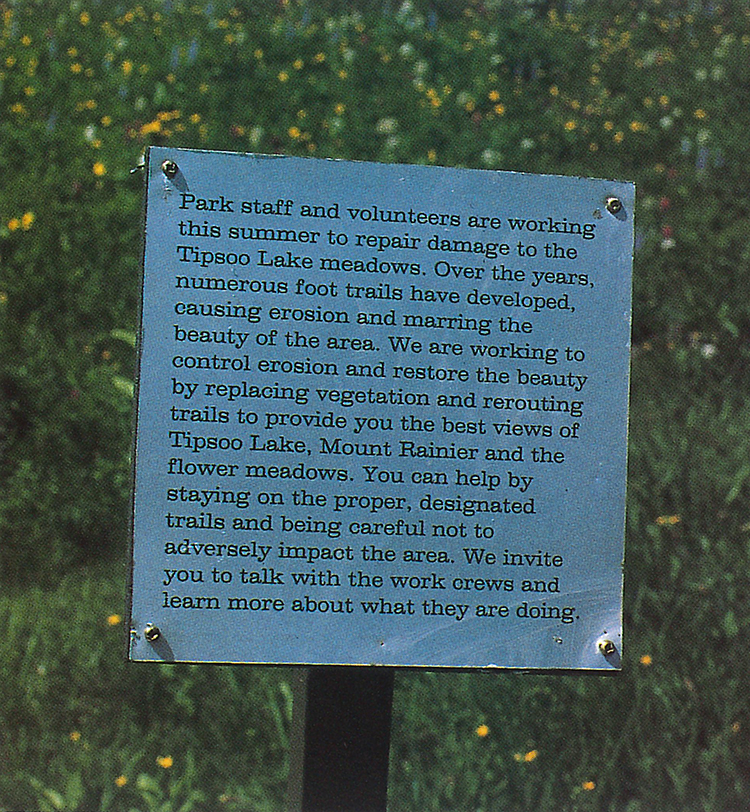

Although there are established pathways, visitors over the years had created more than 900 of their own. Some were narrow paths of compacted ground while others were three-foot-deep trenches. Public education efforts kept some, but not enough, visitors on the established trails. Signs in the meadow that said “Please stay on trails—meadow repairs” (which were used whether or not repairs were actually underway) didn’t work.

The sign that worked: A long explanation of the reasons visitors should stay on official trails kept more Mt. Rainier tourists on the right path. Photo by Peter Thompson.

The right sign can change visitor behavior, Johnson adds. An earlier study at Crater Lake National Park tried to stop people from feeding the ground squirrels junk food. A sign reading, “Beware, ground squirrels known to be carriers of bubonic plague,” proved hard to ignore. The statement (true although the actual risk is minuscule) was twice as effective as saying the squirrels’ natural foods were better for them than human food.

For Paradise Meadows, Johnson helped devise ways to measure the reactions of 12,000 visitors to various signs. Without any signs, 7 percent of the people strayed off established trails. Nearly as many, 5 percent, wandered off trails when confronted with the “meadow repairs” sign or one with the figure of a hiker covered by a red circle with a diagonal slash.

Adding two words, “No hiking,” to the sign with the slash symbol made the message more forceful: only 3.5 percent of the people drifted. Appealing to people’s environmental consciousness with a sign about needing to “preserve the meadow” had the same effect. As did a humorous sign that said, “Do not tread, mosey, hop, trample, step, plod, tiptoe, trot, traipse, meander, creep, prance …” and so forth for another 15 words from someone’s thesaurus.

The best sign, one ignored by fewer than 2 percent of the visitors, said simply, “Off-trail hikers may be fined.” Like the bubonic-plague message, the threat of a fine is linked to one’s personal welfare, Johnson says, and thus more effective.

The study also found that having a uniformed person present made a big difference. “This person was in a simple green uniform, no badges, no patches, no guns—nothing,” Johnson says. “Without saying anything and without any signs at all, fewer than 2 percent of visitors left the trail.” The uniformed person also made each of the signs more effective.

Those differences represent a lot of feet, Johnson says. Using effective signs instead of lame ones may be the difference between acceptable and unacceptable resource loss.

Today’s visitors to Paradise Meadows won’t see any more of the “meadow repairs” signs. Instead the park uses the humorous sign and the one about staying on the paths to “preserve the meadows.” After the 1985 tests, the park also scheduled more uniformed employees to rove heavily used areas.

Although off-trail hiking continues, the sign with the most punch—threatening fines—is nowhere to be seen. The parks are there for the people, and rangers are loath to use signs that seem harsh. In the nationwide survey, more than 40 percent of national park managers said it wasn’t appropriate to threaten fines even if visitors don’t follow the rules.

This user-friendly attitude almost torpedoed a research project at Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument, where a UW graduate student was trying to discourage visitors from taking pumice scattered along trails. The best sign turned out to be, “Violators who remove ash or pumice will be subject to prosecution.” While the research was underway, a forest supervisor who didn’t know about the experiment saw the sign and hated it so much he yanked it out on the spot.

“Park managers want people to feel welcome and are leery of taking steps that might put off visitors,” Johnson says. “It’s a difficulty that might be resolved if managers had more information.” For example, well over 90 percent of visitors encountering a uniformed person at Mount Rainier—a person who might have been viewed elsewhere as an authoritarian figure—had neutral or positive feelings.

Graduate student Vande Kamp and Johnson recently reviewed scientific literature on “non-compliant” behavior to better understand how to motivate visitors. Studies covered everyday misbehavior, such as jaywalking or employees who won’t turn off the lights when they are the last to leave the building. The literature helped them put together a suggestion list for our national parks that takes advantage of human nature. Among the ideas are:

The kinds of people causing trouble at public areas has been an interest of Grant Sharpe, professor emeritus with the UW College of Forest Resources, for 30 years. His work has taken him to well over 100 public areas across the nation.

Little old ladies in hiking boots—whom you might expect to be more respectful of rules than the general public—were just as bad as anyone else when it came to picking up volcanic pumice along trails in the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument, Sharpe says. This was in spite of signs asking that the pumice and ash be left alone so future visitors could see them.

One time, Sharpe came across a young boy carving his initials in a wooden bridge built more than 50 years ago. A case of unsupervised kid’s stuff, right?

“Well, his parents were right there admiring junior’s handiwork,” Sharpe says.

City campgrounds, state recreation areas, Bureau of Land Management property—all suffer the same problems as our national parks. Sharpe remembers visiting a British Columbia provincial park on Vancouver Island that spent $50,000 every five years to have initials and symbols smoothed from the tops of their picnic tables.

Over the years many of Sharpe’s students became park interpreters, so he suggested having interpreters inform the public about the cost of the damage. The effort is particularly important for parks such as Rainier or the Joshua Tree National Monument a few hours from Los Angeles. Both are near fast-growing urban centers and can expect use to increase rapidly during the next 20 or 30 years.

Hardest hit will be the park’s “frontcountry,” places that are readily accessible. For example, more than 60 percent of visitors to Rainier stop at Paradise Meadows and most of them stroll and take pictures within half a mile or so of the parking lot. Johnson’s nationwide survey estimates that frontcountry areas have sustained $66 million in repairable damages and will need $16 million a year for cleaning up litter, graffiti and the like.

Especially vulnerable are historical, archaeological and paleontological sites in the frontcountry. Arizona’s Petrified Forest National Park is one example. The park has petrified trunks of trees from forests that stood 230 million years ago, about the time many reptiles, including dinosaurs, appeared on Earth. Even with vigilance, frontcountry sites in the park are being picked clean of any hunks of petrified wood small enough to lift.

Backcountry costs, though smaller, still weigh in at $14 million for repairable damages and $3 million for clean up.

“Much of this is the creeping, insidious impacts of minor rules violations that, in the long run, are more destructive than blatant vandalism,” Johnson says.