When looking at the timeline of Paul Allen's life, there's one theme that seems to tap into all of the other themes: he liked to collect things. Airplanes. Guitars. Paintings. Pop culture mementos. Movie memorabilia. Sports teams. Big companies. Little companies. Entire city blocks.

In this visual obituary, we trace the major plot points of Allen’s life using museum items as our guide. These objects are on display at the Living Computers: Museum + Labs in Seattle’s SoDo neighborhood, which Allen opened in 2012. Along the way, we outline the history of computing—from punch cards to floppy disks to virtual reality. It’s a vast and complex history, but the consummate collector left us plenty to play with.

As the precursor to floppy disks, CDs and thumb drives, these cards were used to store programs in the early days of computing. Paul Allen had an early interest in science and engineering as a child in North Seattle. His father Kenneth, ’51, worked in the UW Library System and eventually became the associate director. His mother Faye, ’50, was a librarian at Suzzallo from 1949 to 1951 and later a school teacher at the Ravenna School, where Allen went until sixth grade. After that, his parents enrolled him at Lakeside School in North Seattle.

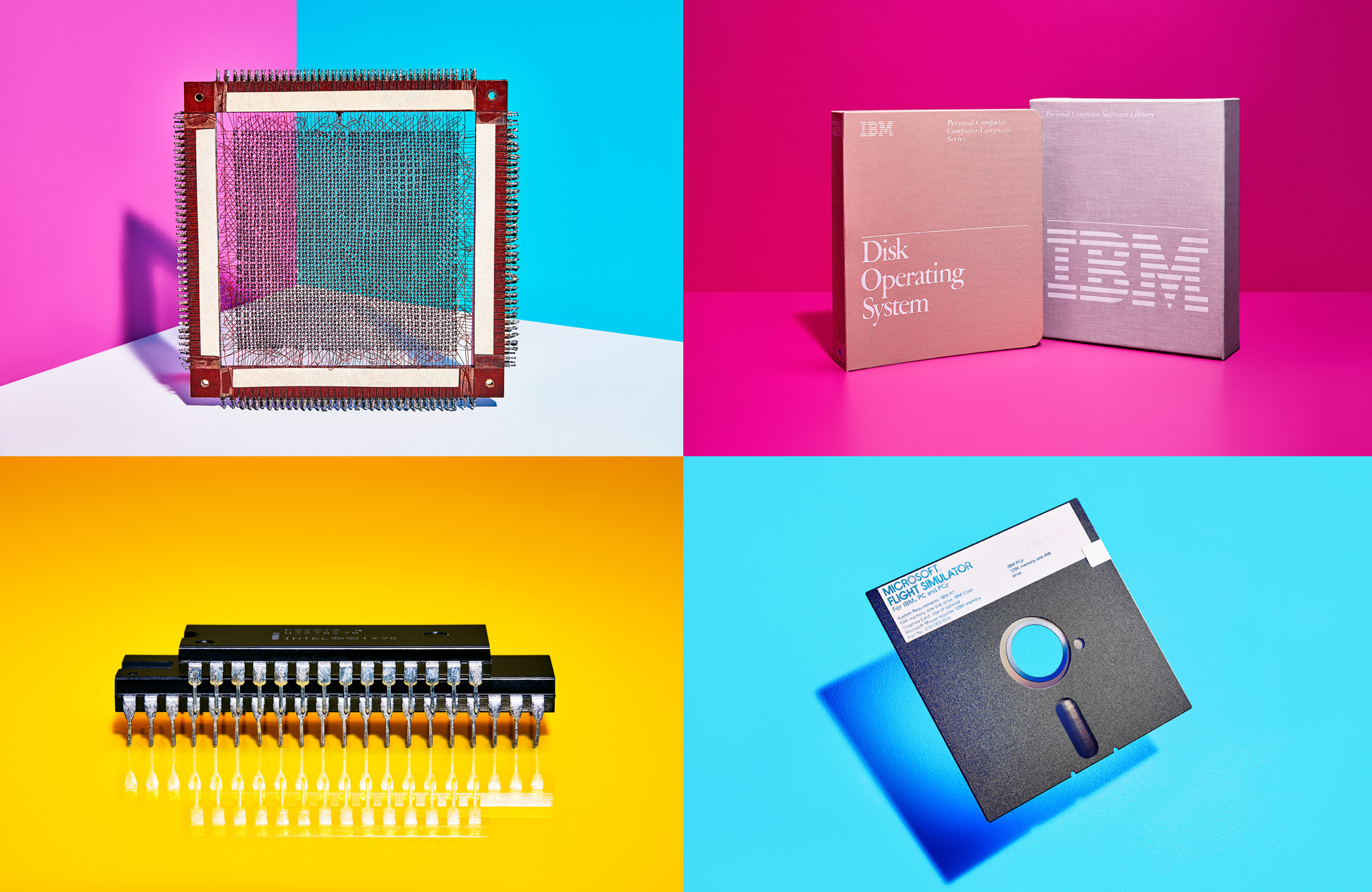

From the 1950s to the 1970s, mainframe computers stored their memory in grids of handwoven magnetic-core. By using magnets and electrically charged wires, the machines could read and write information which could be stored when they weren’t plugged in. Mainframe computers were mostly found at major universities, big companies or government institutions. Access to such machines was hard to come by, but Lakeside was no ordinary school.

“Lakeside was the most prestigious private school in Seattle,” Allen wrote in his 2011 memoir, “and I wanted to nothing to do with it.” But he soon became intrigued by the challenging curriculum, and eventually he got hooked on playing with the school’s advanced technology. In 1968, Lakeside received a Teletype Model 33, an electromechanical typing machine that students could use to log on to a remote mainframe computer. Allen recalled seeing a “gangly, freckle-faced eighth grader edging his way into the crowd around the Teletype, all arms and legs and nervous energy. He had a scruffy-preppy look: pull over sweater, tan slacks, enormous saddle shoes. His blond hair went all over the place.” Guess who.

Twelve-year-old Bill Gates was two years younger than Allen, but the two became fast friends. A year later, Gates was already suggesting they would run their own company one day. Besides coding together at Lakeside, they haunted the computer lab at the University of Washington—until they got kicked out of it. This early access to high-end computers is how Allen and Gates became expert coders.

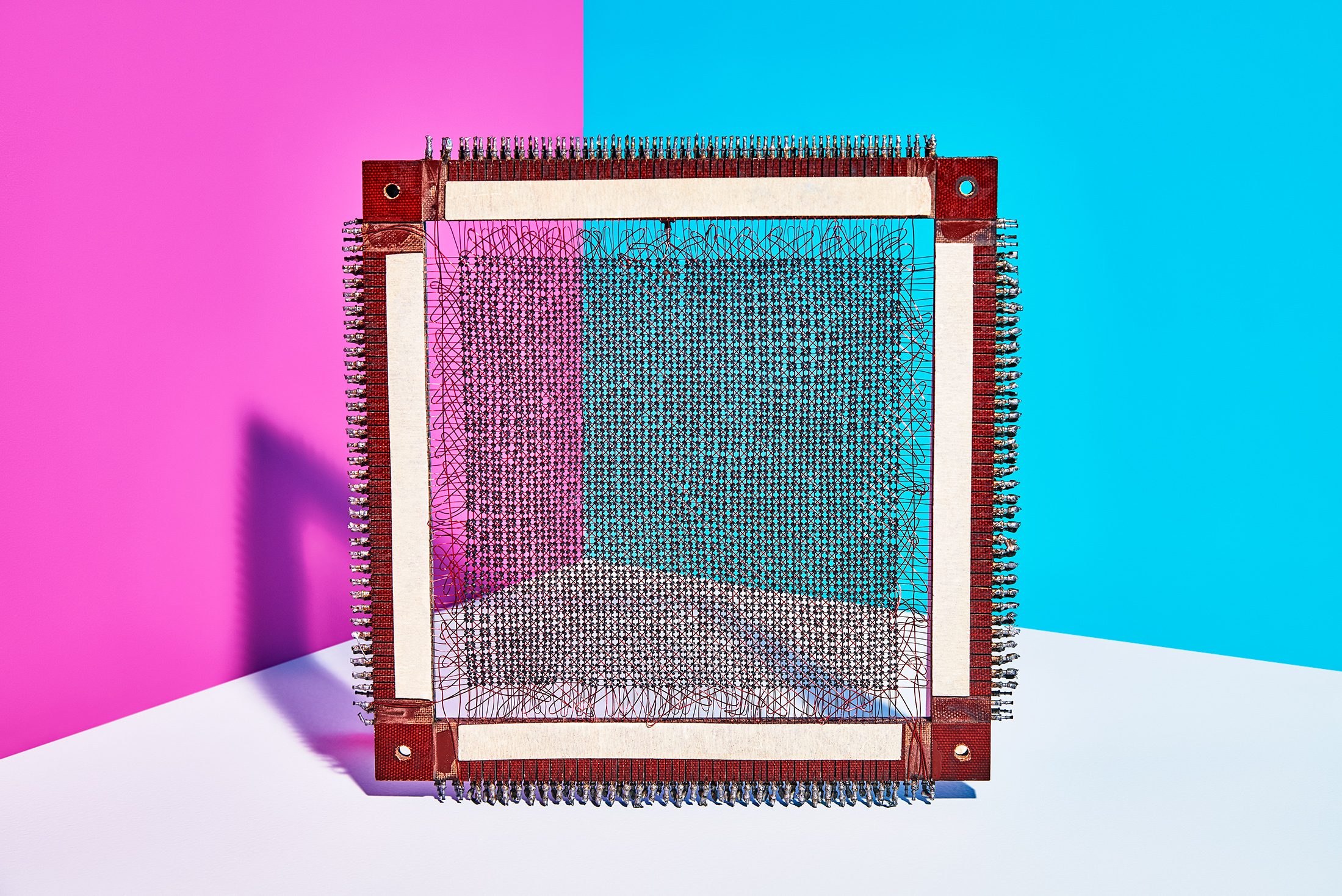

Microprocessors sparked the computer revolution and drove Microsoft’s growth. Intel was at the center of these advances. After graduating high school, Allen went off to Washington State University, and since Gates was still in high school, the two continued to code on projects together.

After graduating, Gates moved to Boston to attend Harvard. Allen then dropped out of college and began working as an engineer in Boston. Gates soon dropped out, too. (Gates said Allen convinced him to drop out, while Allen claimed Gates convinced him to move to Boston.) It’s no coincidence that in the same year, Intel released one of its most important microprocessors, the Intel 8080. This tiny piece of hardware was so important to Microsoft’s early success that the company’s first phone number ended in 8080. Today, Intel processors can still be found in most computers.

In 1974, Allen and Gates saw an ad in a magazine for a new computing kit called the Altair 8800, which came with the latest Intel microprocessor and sold at a relatively low price point. Over the next few weeks, they wrote a programming language for the Altair, which became the first product that Microsoft ever sold.

The company formally launched in April of 1975, headquartered in New Mexico. Allen, the Chief Technologist, is the one who came up with the name, which represents their expertise: microcomputer software. Four years later, the company relocated to Redmond.

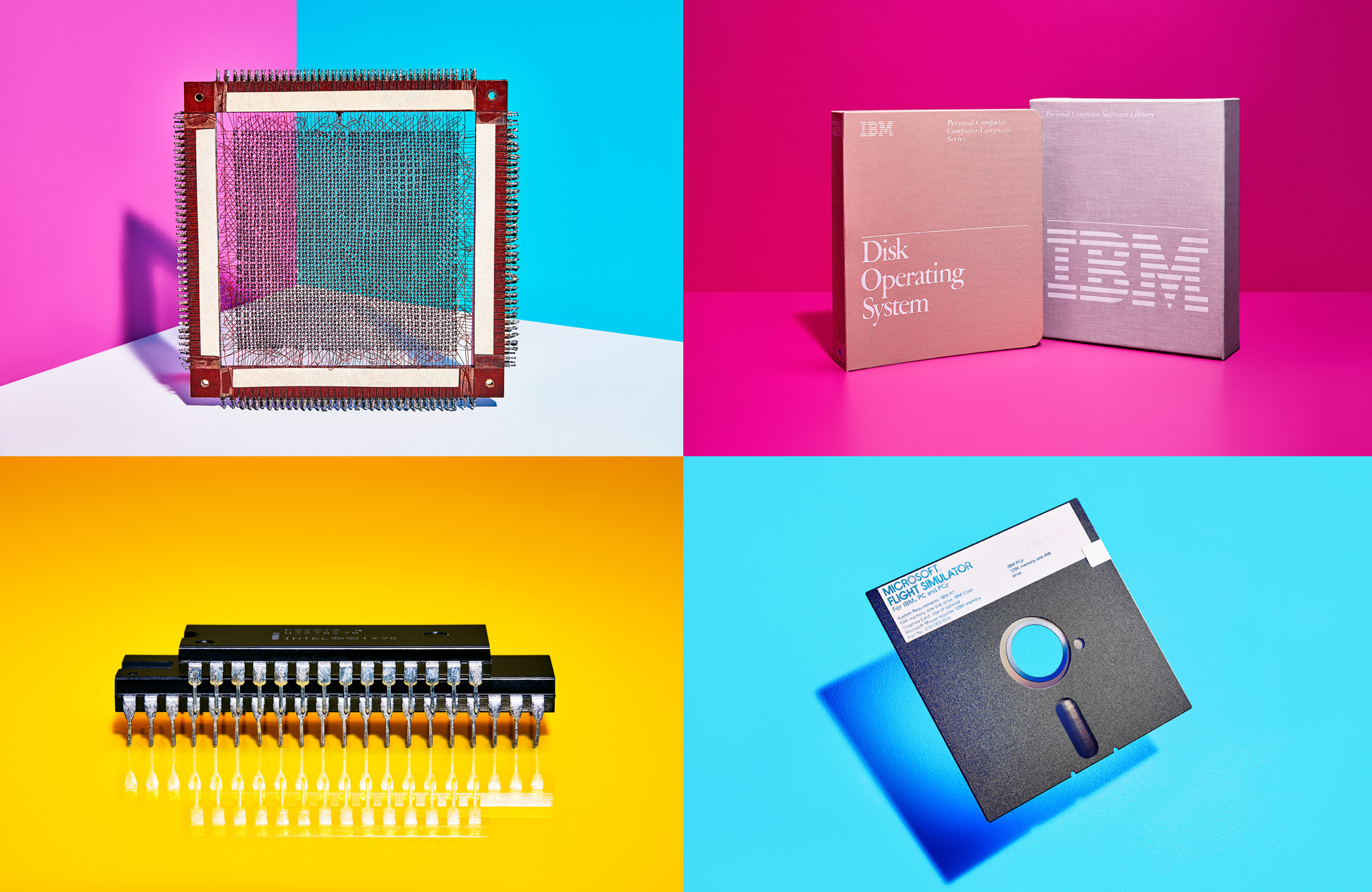

In 1980, Microsoft was approached by IBM, a heavyweight of the computing industry, to develop an operating system that could work on a mass-produced personal computer. But Microsoft didn’t build it from scratch: In a deal brokered by Allen, the company bought an operating system from another business, Seattle Computer Products, and relicensed it as MS-DOS.

The product would be rolled out alongside the IBM PC in 1981, which set Microsoft up to fulfill its famous mission statement: “A computer on every desk and in every home running Microsoft software.” From that point on, the terms PC and Microsoft would forever be linked.

Until the release of its PC in 1981, IBM mostly produced mainframe computers. Its partnership with Microsoft allowed it to break into—and for a time dominate—a burgeoning market. Meanwhile, Microsoft’s partnership with IBM was a turning point in the company’s history. In a shrewd business decision, Allen and Gates retained ownership of DOS, which meant they could license it to other personal computing companies when the market started to grow beyond just IBM. MS-DOS paved the way for Windows, released in 1985.

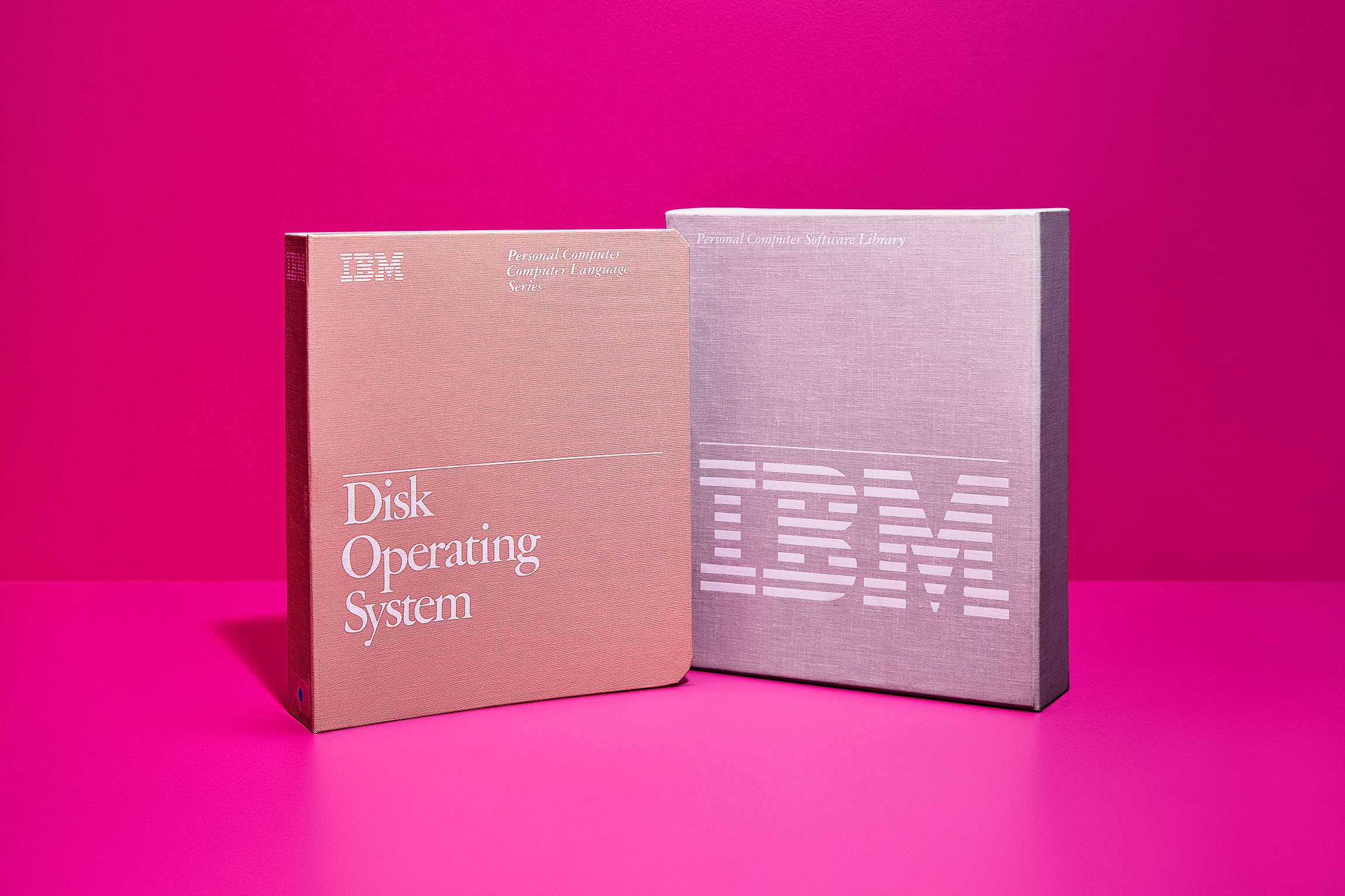

A video game called Flight Simulator was already out on computers like the Apple II, which had an 8-bit processor. But the IBM PC had a 16-bit processor, which meant that it could handle more advanced graphics. Microsoft wanted to show off these graphics, so Allen and Gates licensed the latest version of Flight Simulator for the IBM PC. Microsoft continued to release new versions of the game, which is the oldest surviving software that you can still buy from the company.

Allen later became a prolific airplane collector and his collection is now on display at the Flying Heritage & Combat Armor Museum in Everett. His father was a World War II veteran who landed on the beaches of Normandy during D-Day, but that’s not why Allen became interested in warplanes; that came from his dad’s post at the UW Library System. “I would go in the university stacks … I’d spend hours reading about the engines in some of those planes,” Allen told Forbes. “I was trying to understand how things worked—how things were put together, everything from airplane engines to rockets and nuclear power plants. I was just intrigued by the complexity and the power and the grace of these things flying.”

In February of 1983, Allen left his executive role at Microsoft after a cancer diagnosis. Before he formally stepped down, he overheard Gates threatening to dilute his stocks. Gates was talking to Steve Ballmer, who had been on the business side of Microsoft since 1980. Allen was livid and refused to sell his shares, and he remained on the board until 2000—the year Ballmer succeeded Gates as CEO.

It’s worth noting that, before the falling out, Gates did try to mend fences with a six-page handwritten letter dated December 31, 1982. “During the last 14 years we have had numerous disagreements,” Gates wrote. “However, I doubt any two partners have ever agreed on as much both in terms of specific decisions and their general idea of how to view things.” But the strain on their relationship would take time to heal. Meanwhile, Allen’s father died in November of ’83, perhaps capping off the most tumultuous year of his life up to that point.

Announced by a Super Bowl commercial directed by Ridley Scott, which infamously compared the IBM PC to George Orwell’s “1984,” the Macintosh forever changed the trajectory of personal computing—and the history of Microsoft. Apple had released computers since 1976 (an earlier model, the Apple II, even supported Microsoft hardware and software), but the Macintosh was a new beast. It was the only computer company that survived the rise of the IBM PC, allowing Apple to hold onto a relatively small but significant share of the industry.

Apple and Microsoft were at times bitter rivals. Their leaders clashed ideologically, their brands jabbed each other in TV ads, and their loyal followers took sides like diehard sports fans. But both the successes and the failures of these two companies are intertwined. These days, their turf war has expanded into the world of tablets and cloud-based software.

As the CD took over the music world, Allen dove wallet-first into his obsession with the arts. He announced plans to bring a music museum to Seattle in 1994, and The Experience Music Project, a shiny and vibrant building inspired by Allen’s love for Jimi Hendrix, would open six years later. (It eventually expanded into MoPOP, The Museum of Popular Culture.) A longtime guitarist, Allen joined a band called Grown Men in 1996, and in true rockstar fashion, he started dating a fellow celebrity, professional tennis player Monica Seles (they quietly called it quits and Allen never married). He would later form a blues-rock group called Paul Allen and the Underthinkers, releasing an album through Sony in 2013.

Music wasn’t the only art form that moved Allen. By the late ’90s Allen had launched a movie production company, Vulcan Productions, and purchased the Cinerama, a theater in downtown Seattle that projects 35mm and 70mm films. He also began to collect paintings, sculptures and other forms of rare, expensive and avant-garde artwork. It’s debatable whether Allen was a connoisseur of the arts or simply a wealthy collector-investor (“He means well but has more money than vision,” jabbed a 1994 piece in Wired). Still, his expansive archive of the arts—from Monet to Spielberg to Hendrix—shows a different side of a man whose fortunes came from computing.

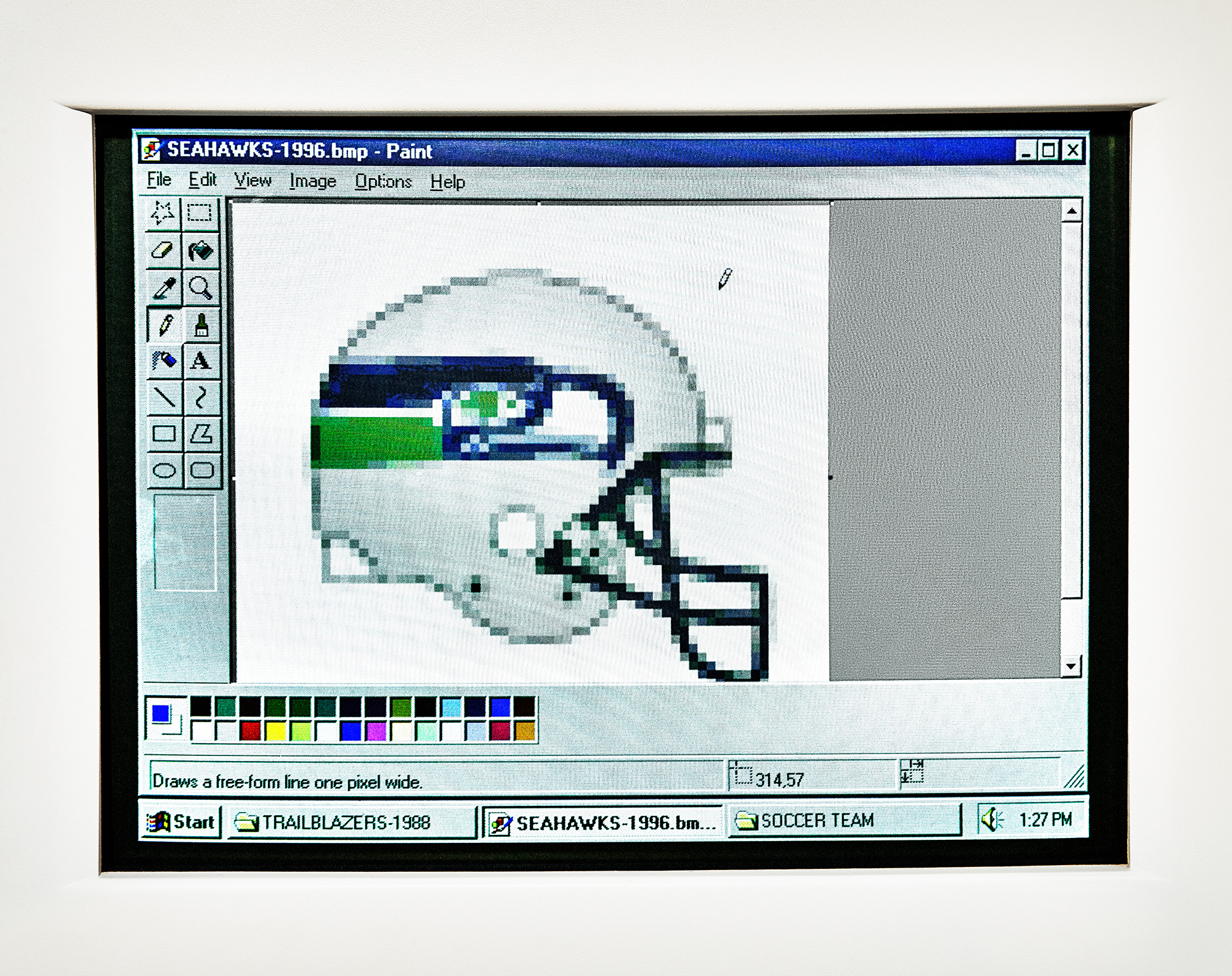

In the ’90s, Microsoft continued to paint the future of computing by releasing new versions of its operating system. Windows 95 built off of the success of MS-DOS to produce a powerful operating system that PCs still run today. Microsoft Paint, meanwhile, came installed with Windows as early as 1985, allowing kids across the world to swap out their crayons for pixel brushes.

Allen, the majority owner of the NBA’s Portland Trail Blazers since 1988, purchased the NFL’s Seattle Seahawks in 1997—saving the team from a potential move to Los Angeles. The franchise went on to appear in three Super Bowls, winning one. With the departure of the SuperSonics they became the defining pro sports team in the Pacific Northwest. In 2006, Allen became a minority owner of the Seattle Sounders.

Allen envisioned a “wired world” and invested in internet infrastructure in 1998, buying a company called Charter Communications. His goal: to help bring high-speed internet to every desk. The company later became a huge financial loss for Allen. Still, Vulcan Capital, the investment arm of Allen’s fortune, found success by backing other internet-based companies such as America Online, Ticketmaster, Alibaba and Redfin.

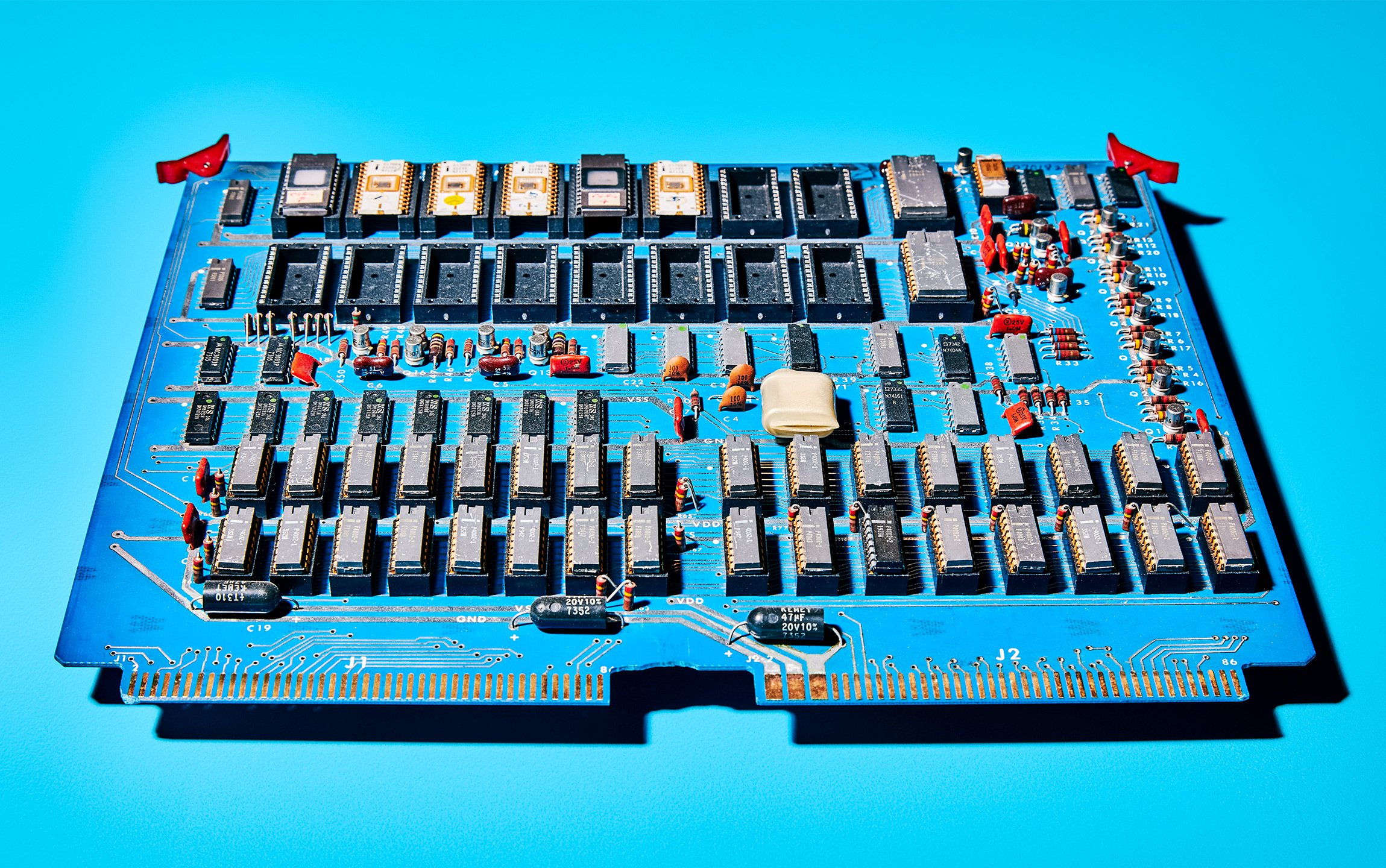

Over the years, the computer’s circuit board evolved from a single board (above) to a far more complex landscape known as a motherboard. The Seattle skyline has seen the same type of dramatic change, in part due to Allen’s real estate investments, museums and taxpayer-funded football stadium.

In particular, Vulcan Real Estate turned South Lake Union into “Seattle’s fastest-changing neighborhood,” according to The Seattle Times. In 2007, Vulcan agreed to lease 1.7 million square feet for Amazon’s new headquarters. By 2010, when Amazon moved in, Vulcan had also developed blocks of buildings for other tech companies and medical research firms. The development is not without controversy. The makeover of South Lake Union—once a blue-collar stretch of industrial buildings and single-family homes, now a high-tech commercial zone sprinkled with high-rent residential units—represents the intersection of big tech and gentrification.

One of the research institutions in South Lake Union is the Allen Institute for Brain Science, which Allen created after his mother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in 2003. She died in 2012.

Microsoft continues its foray into the future with the HoloLens, an augmented reality headset. At the time of his death from cancer in 2018, Allen and Vulcan were investing in virtual and augmented reality technologies, challenging their team to create immersive experiences that didn’t require headsets.

In 2017, Allen endowed the UW with $40 million to open the Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering (Microsoft contributed an additional $10 million). The Allen School recently opened the UW Reality Lab, which allows students and faculty to experience and research AR/VR technology. Like the massive mainframes in the computer labs of Allen’s youth, perhaps this place could become a second home to the pioneers of tomorrow’s technology.