While many of our alumni know of your generous contributions to the University, most don’t know of the UW connections going back to your childhood. Your father Ken Allen began his career with the University libraries in 1951, two years before you were born, and was associate director of the libraries from 1960-1982. Did your Dad open the resources of the UW libraries to you when you were a child?

I spent many weekends in Suzzallo Library as I was growing up. I remember spending hours just combing through the stacks of musty books, including early books about computers. Books about science and aviation in particular were some of my favorites.

Did your family have season tickets to Husky games?

Yes, my father had season tickets for the Huskies for my whole childhood and I remember going to many Husky games with him. One of the reasons that I really wanted to have an open-air stadium for Seahawks Stadium is that I have fond memories of wandering around Husky Stadium with my Dad, eating hot dogs and being able to watch the Huskies play outdoors in the elements—I think it’s one of the best parts about football!

Do you recall attending any open houses or science fairs at the UW that might have sparked your interest in computers?

I went to science fairs many times and had a lot of fun. More than anything it enhanced my love of science— and I carry that excitement with me today. I am particularly interested in how the brain works, and what we might be able to learn by looking at the role of the human genome in the function and anatomy of the brain.

The time you and Bill Gates spent at Lakeside School exploring the world of computers has already achieved the status of legend. But what isn’t as clear are the UW-related facilities you took advantage of during that time. For example, four UW faculty and staff created the Computer Center Corporation (known as “C-Cubed”) on Roosevelt Way, which you and your Lakeside friends helped debug. The center had one of the first commercially available, time-sharing PDP-10 computers in the nation and the owners gave you free computer time to find all the flaws in the system. In one interview you recalled how you would often ride the bus to the U District, stay at the computer center and then eat pizza at Morningtown Pizza on 41st and Roosevelt. Are these tales pretty accurate?

Yes. These are accurate. As many people know, back in the early ’70s I would come over to campus and sneak into the graduate computer center at Roberts Hall to get some time and experience on the machines. Eventually Bill and some other guys from Lakeside came over too. I eventually got caught by an assistant professor in the lab—he didn’t recognize me from any of his classes, and I had to admit I wasn’t a UW student either. But he knew that we had been helping other students, so he told us that if we helped people while we were here, we could stick around. We were thrilled at the opportunity and although we were just high-school students, it was so cool to be on campus, working alongside college students, and exploring our new passion for computers, which were still such a novelty. We eventually wore out our welcome but it was a really transformative and positive experience to have that opportunity.

One of your assignments was to try to crash the PDP-10. Was it a game for you and the others—trying to see how quickly you could bring the machine down?

Crashing the PDP-10 was at Computer Center Corp., off-campus. We just tried to figure out things that caused the system to crash, so that we would be able to keep using the machines for our own experimental projects (it’s how we earned extra time for ourselves). I think we also did crash the [Burroughs] B-5500 in Roberts Hall a few times as well.

I’ve also read that you tried to understand the inner workings of the PDP-10 and that the C-Cubed programmers would only give you one manual at a time.

They basically spoon-fed me one manual at a time to see what would happen, but I really gobbled them up, and was soon doing system programming in assembly language on the BASIC compiler, and that was just at the age of 17.

Wasn’t this a difficult way to learn about computers?

I think that given the options at the time, the most effective way to learn was going hands-on with what was the top machine at the time, learning about how it worked, what it took to “make it or break it.” I think people learn best by being hands-on, whether it’s exploring computers, learning to play music, etc.

Today we have amazing resources available, and the commitment to computer science represented by this building (the Paul G. Allen Center for Computer Science and Engineering) will result in advancements we can barely imagine now—and a large part of it is about having more lab space and computers that young people can get their own experience on. In the way that we could not conceive of how computers would change our lives, in say 1970, we will look back at this time 20 or 30 years from now and realize how little we comprehended. I have no doubt that this center will play an important role in the discoveries that will effect how we all live, work and play in the future.

It’s pretty well known that a bunch of the Lakeside students—including you and Bill Gates—got into the PDP-10’s accounting system and gave yourself free computing time. When you were caught, the group was banned from the C-Cubed computers for the summer. Can you tell me a little about how you worked around the ban? Supposedly your Dad found an electrical engineering professor with a C-Cubed account that you could use.

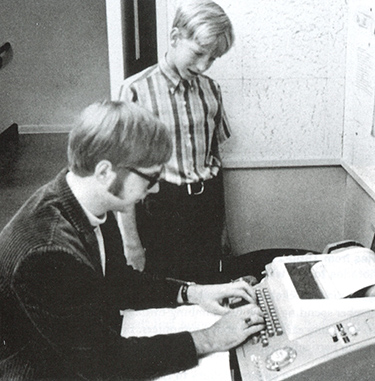

Bill Gates, an eight-grader, looks over the shoulder of Paul Allen, a tenth-grader, in this 1968 photo taken at the Lakeside School’s computer desk. Photo courtesy of Lakeside School.

We were so eager to get time and experience on the computers that we did almost anything to figure out how to get on the schedule. We really took some risks back then—you have to remember that unlike today when so many people have computers of their own—in those days there was one computer for thousands of people. So to get any hands-on experience was really difficult and time consuming, but something we were really focused on.

Do you remember which building it was in?

It was Roberts Hall where I spent most of my time, but I also spent a lot of time at the HUB having lunch and reading manuals. The hamburgers were pretty good back then!

If C-Cubed had never been founded, do you think you would have continued your interest in computing?

Absolutely. My main interest has always been in science and technology. If it wasn’t an open computer door at Roberts Hall I would have found another way to satisfy my curiosities—I was just very fortunate that the UW had the facilities, even way back then, which ended up giving me opportunities that were close to home.

When C-Cubed went bankrupt, it seems you started to hang out more at the UW Computing Center. According to one account, you saw your first computer game—Spacewar—and your first computer mouse at the UW. Is this true? Can you tell me anything about those discoveries—did you feel that they were going to have a impact in the future?

There was a version of Spacewar that ran on the IMLAC terminal, and I later saw another version on the PDP-1 at Harvard that had been written earlier by Steve Russell—who ironically was also one of the key programmers at CCC. I eventually saw mice on Altos at Xerox Parc, and was blown away by how they worked and the great GUI that had been developed at the time— it was really exciting to see how the envelope could be pushed ahead on how people could use computers and interact with software.

In one interview you described how you just sat down and started to use a Xerox time-sharing computer—XDS Sigma 5—and everyone thought you were a UW student. How were you eventually found out?

I think people could tell I was a bit too young to be a student there. I had been using the computer for some time before an assistant professor eventually walked up to me and asked if I was in any of his classes. I of course could not lie so I told him no, I was not in any of his classes, and he went on to ask if I was even enrolled in the UW. Again, I had to tell him no. But I was given the chance to keep using the labs here because I agreed to help students when they came in with a problem. And from that point on, there was no turning back.

Did you also get free time on the UW’s CDC 6400? I understand these were still the days of punch cards and batch systems. According to the computer science and engineering department, you also accessed a DEC PDP-10 operated by the Medical School and a Burroughs B5500 operated by the Academic Computer Center. Why were you testing out all these different systems?

I believe I paid for time on the CDC 6400, but it was fairly cheap—the only problem was that the programming was done on card decks, and I missed using terminals from my experience with the CCC PDP-10s. I was really fascinated by the differences in instruction sets, operating systems and languages on each of the machines—back then each mainframe was a computing world in its own right. We worked on everything from compilers to operating systems to games, class scheduling programs, and even a computer matchmaking program. It was a lot of fun, and there were always a lot of ideas and challenges.

Have I left anything out about exploring UW computer systems?

I don’t think so. Again, it was such a great opportunity and I’m lucky that the UW let us spend the amount of time we did in the computer center. I think it’s so important to give young people the opportunity to explore their passions – whether it’s computers and software, or music, or studying entrepreneurial skills – whatever makes them excited about life and learning. I hope that my support of the new Allen Center will help create those opportunities for students, in the same way that building EMP has helped get kids excited about music, etc.

With all your UW connections, some of our alumni might wonder why you didn’t apply to the UW when you graduated from Lakeside. Was there a particular reason why you chose to go to WSU instead?

At the time UW didn’t offer an undergraduate degree (in computer science) and WSU did, so I went to WSU.

If we can jump ahead a few years to the early days at Microsoft, was there much interaction with the UW? I think some of your early employees were UW graduates. Tim Patterson, the author of QDOS and later a Microsoft employee, was a UW alumnus. So was there some interplay there?

Yes, of course. The UW has always had a great program—it’s one of the top five computer science programs in the country—and Microsoft has definitely benefited from the University’s program. It’s important for academic institutions and business organizations to work together, to share resources, to “cross-pollinate” each other’s efforts in a way because together they can accomplish really good things for young people, the field of technology and the community as a whole.

When you moved the company from Albuquerque, was there some consideration of moving to the Silicon Valley? Was the UW also a factor in coming back to Seattle?

Albuquerque was a great place, but I missed my family and missed living in the Northwest. I’m a Seattle native and my roots are deep here—Bill and I thought it was time to go home and see what we could accomplish in Seattle. Bill and I also thought that people in the Bay Area seemed to change jobs every 18 months, and we would have a more stable and focused workforce up in Seattle than if we moved to the Bay Area—and is was much easier to hire people and relocate them to Seattle than to Albuquerque.

Jumping ahead a few years, you left Microsoft in 1983 and took some time off. Sadly, your father died that same year. Just five years later, you decided to make what I believe is your first major philanthropic gift: $11.9 million to create the Kenneth S. Allen Endowment at the UW. Can you tell us how you got the idea for the gift?

University Libraries Associate Director Kenneth Allen (left) watches as the Anglican Archbishop of Dublin, the Rev. George Otto Sims, signs a guest book in the this 1960 photograph. Courtesy MSCUA, University of Washington Libraries

My father had worked at UW as the associate director of libraries and obviously I had many great experiences on campus—from the library to the early computer experiences we talked about. My family wanted to give back to the University to help make sure that students for many generations to come have access to the tools they need—whether it’s an outstanding library or a great computer center or a top-notch arts center (the Faye Allen Center for the Visual Arts at the Henry) that can make a difference in their lives.

I happened to be at the regents meeting where the board officially accepted your gift—at the time one of the largest ever given to the University. I remember Mary Gates standing up and making a kind and personal statement of appreciation, how she had known you for so many years. It was very moving. Can you tell us a little bit about how you felt that day?

I had known Mary for a long time and she was a really inspirational woman—I had spent a lot of time with the Gates family during our years at Lakeside, and our families knew each other well, and Bill would also come to visit me too. Mary did so much for the community and was a wonderful leader in our region—it was really heartwarming to have someone like her make such thoughtful remarks.

Do you keep tabs on how the endowment has enhanced the libraries?

Any time you can use your resources to make a positive and lasting impact, that’s a great opportunity, and I look for ways to do that with my philanthropy – from the library to the computer science center. The library has strong leadership and a terrific staff – I’m glad my gift helped them continue their work and give students access to important literature from throughout history. My mother is also a huge fan of books, so having part of the library endowment be focused on book acquisition was an important component for me and my family.

When you walk past the Allen Library on campus, you must think about your Dad and how proud he would have been to see his name on this splendid building. It is one of my favorite modern buildings on campus, since the architect tried to place it in context with our Collegiate Gothic architecture. Do you ever just walk around in there—and in Suzzallo—and take it all in? Does anyone recognize you if you do?

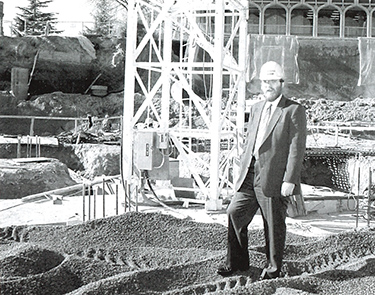

This 1987 photo shows Paul Allen standing on the construction site of the Kenneth S. Allen Library, named after his father, an associate director of the libraries for 22 years. Photo by Mary Levin.

I always love coming to campus—I spent a lot of time here back in the old days and I’m really pleased I can support the University now. The regents and the other leaders at UW have always been very thoughtful and strategic about how and when they add new facilities—and the architectural impact those new buildings will make. It’s a beautiful campus and we’re really luck to have it in Seattle. I do love the architecture of the Suzzallo addition named after my father, and especially how nice the Donald Peterson Room is. And the inside of the building is really well done.

I do get recognized when I go out in public sometimes, but it just depends on the time and place—and it never deters me from doing anything. It’s nice when people say “hi” or “thanks”—it helps me remember that I’m able to help the community in some way and that my charitable work is making a difference for people.

Another of your major UW gifts is $5 million to the Henry Art Gallery to establish the Faye G. Allen Center for Visual Arts.

I think it was (former Regent) Sam Stroum who approached me about the Henry gift. He and I both wanted to do something that recognized my mother and her love for books and art.

One of the reasons we asked to interview you is the new Paul G. Allen Center for Computer Science and Engineering, which had its dedication in October. Do you ever reflect on the irony here—someone who had to beg for time on UW computers when he was in high school now has a UW computer building named after him?

The new Paul G. Allen Center for Computer Science and Engineering opened in late September. Photo by Lara Swimmer.

When I was first approached several years ago about somehow supporting UW’s computer science facility, I was excited to be able to help. I had some great experiences here, and those early days in the computer lab at UW were a milestone on the way to starting Microsoft. Looking back, it’s gratifying to remember that the University welcomed us, and although we weren’t students, they embraced us and let us pursue our interests. It made a world of difference to us and gave huge momentum in what was to come.

There are personal and philanthropic reasons why you gave $14 million to help complete this project. Can you explain them to our readers?

On the personal side I have some great memories of visiting the campus with my father—be it to sneak into the graduate computer lab or to attend a Huskies football game. And of course this is where I really got my first chance—my first opportunity—to follow my passion for computers that ultimately helped launch my career.

On the philanthropic side I really can’t wait to see what the future holds—what amazing inventions and discoveries are on the horizon—thanks to the hard work and brilliant minds of the young people in the program. If the new facility helps support that vision and the students and faculty bringing it to reality, then it’s always worth it.

You’ve gone on several tours of the new building. What is your reaction to it?

Stunning—it’s a really fantastic facility. The center has exceeded my expectations on many levels. There is so much lab space that I know many students are going to get even more hands-on experience than ever before. And although I’m proud to have supported this beautiful and unique facility, what really sets UW’s computer science program apart are the people—the faculty and the students. The Allen Center is a wonderful home for the program, but at the end of the day it’s the excitement, intelligence and innovation of the men and women in this organization that make it what it is. The faculty here is unparalleled, and the undergrad and graduate students are dedicated and inspiring.

How will this facility help the UW, the region and the world with the latest computer technology?

There are some truly exciting developments in the world of computer science and I am confident that the faculty and students here at UW will be on the front line of what’s to come, from what the future holds in application development, user interface design, form factor (the size and shape of computers) and networking to the innovations yet to come with artificial intelligence and specifics such as language processing and speak recognition—things that can improve computing based on what we learn about how the human brain works.

And pushing the envelope with the ever-elusive “killer app” still excites me and certainly motivates countless students, teachers and researchers here and around the world. Genuinely exploring new ways to draw people into computing – creating something so compelling that we can see another surge in the function and power of computers and how they help people live, work, play and learn—is a great challenge and a wonderful opportunity. And it’s an opportunity that I know the UW CSE program will leverage and exploit—moving forward with passion, zeal and the kind of fresh thinking and creative problem-solving that this school has become known for.

I’m surprised at all the collaborative space in the facility. Ed Lazowska says the cliché of a single programmer hunched over a computer keyboard is horribly out of date. Computer science and engineering today is a much more collaborative process. Would you agree?

Yes it’s true. It’s really a hands-on, team approach that makes it successful.

Another growing tie with the UW is biotechnology. In September, you announced an extraordinary gift—$100 million for the new Allen Institute for Brain Science. It hopes to create a definitive map of the mouse brain genome, what one researcher called the “neuroscience equivalent of the Human Genome Project.” How do you see the UW interacting with this new, non-profit institute?

No other project in the world is focused on building a comprehensive map of gene expression overlaid with anatomical and functional brain data of this scope or scale—what makes this unique is its breadth (the whole brain) and its depth (all the genes related to the brain, which could be 20,000 or more). This is a much needed research effort that will benefit scientists, and their efforts, worldwide—including the important research work that UW is doing. We are expecting the first major release of data to occur in the first quarter of 2004, followed by quarterly updates thereafter. Scientists will be able to download the imagery and supporting data to support their own research efforts.

And the UW is leasing the old Washington Natural Gas building from your real estate company and hopes to have more than 750,000 square feet of biomedical research space located in the South Lake Union neighborhood. How do you see the UW’s role in the overall development of South Lake Union?

UW Medicine already has a presence in South Lake Union at Vulcan’s 60,000-square-foot Rosen Building on Republican Street and Terry Avenue North, which is also used for medical research programs, and at the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance building at 825 Eastlake Ave. E. We are proud to welcome new bioscience companies to the South Lake Union neighborhood and bioscience is a big part of the economy of the future; the industry’s discoveries of new methods to prevent and treat diseases will impact each and every one of us in a positive way. Seattle is fortunate to have such a critical mass of research organizations like UW at the forefront of this life-changing work.