Another side of the city Another side of the city Another side of the city

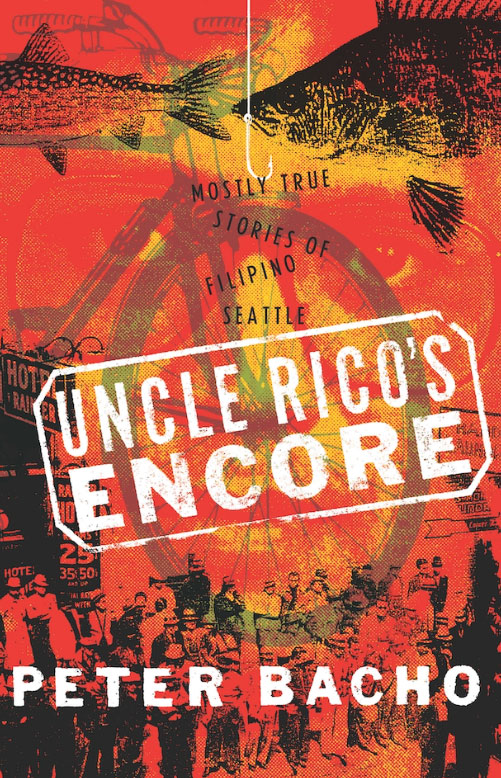

Peter Bacho's seventh book, “Uncle Rico’s Encore: Mostly True Stories of Filipino Seattle,” tells an extraordinary Pacific Northwest story.

Peter Bacho's seventh book, “Uncle Rico’s Encore: Mostly True Stories of Filipino Seattle,” tells an extraordinary Pacific Northwest story.

When writer Peter Bacho thinks of Seattle, his is not the view from a picture postcard. But it is every bit as stunning.

Bacho’s perspective doesn’t include Mount Rainier or the Space Needle. Instead, he sees the city from Beacon Hill, the Chinatown International District and the South End, where he grew up as the child of immigrants in what was at the time one of the country’s most diverse neighborhoods.

He gifts us with these views in his new book, “Uncle Rico’s Encore: Mostly True Stories of Filipino Seattle.” The novelist and short-story writer walks readers through Seattle and through time to reveal his family, his treasured childhood and his community. This is his seventh book. His 1991 novel, “Cebu,” won the American Book Award and put Bacho, ’74, in the firmament of great writers of his generation.

Rick Bonus, professor of American Ethnic Studies, describes Bacho’s latest work as a significant contribution to the canon of Northwest literature. The “mostly true” short stories are elegant and provocative, says Bonus. “Peter has this skill of writing prose that’s really not only lucid, but also filled with energy.” Even if you’re not from Seattle or the Pacific Northwest, you can easily identify with his work, Bonus says. “He’s a master storyteller.”

Bacho also has a deft ability to weave together a vision of a community and city with moments of wonder and cherished memories.

“The Filipino community in the Northwest is very interesting compared to other places in the United States,” Bonus says. The Puget Sound region is home to multiple generations of immigrants. The first to come were farmworkers and laborers. Then there’s a generation of World War II veterans and war brides. Next, a post-1965 generation of educated professionals. And finally, people who suffered under the martial law of President Ferdinand Marcos between 1972 and 1981.

“I wanted a ringside seat to the whole thing. I wanted the story.”

Peter Bacho

“Peter [who was born in Seattle in 1950] straddles those generations. He is able to speak across those generations,” Bonus says. “He is also locating himself as accessible not only to different kinds of Filipinos and different communities of color, but to all of Seattle and readers who are interested in history and culture.”

A lot of the book is autobiographical. “It is a love note to a community, but it is also a love note to a very beautiful city,” Bacho says. He gives readers the rich legacy of Filipino union activism, the charm of pickup basketball games with neighborhood kids, and the intrigue of shutting his eyes tight against a ghost in his bedroom.

Pleasing his parents, he studied law at the UW. “But my heart wasn’t in it,” he says. “I wanted to go to interesting places.” At the time, the Philippines—under the rule of Marcos—was rife with international intrigue. Bacho returned to the UW for a second law degree focused on marine legal affairs that would bring him closer to the interactions between the U.S. and the Philippines. He also used the time to explore Southeast Asian politics. “When the crisis was going to break, I wanted to be one of the few people to write credibly about it,” he says.

He found a home for his journalism at The Christian Science Monitor. Somehow in the thick of working on his law degree and teaching Asian American Studies at the UW, he produced stories for The Seattle Times, the Oregonian, the San Francisco Chronicle and other papers. He faced danger, traveling to the Philippines in the 1980s to report on political unrest at the end of the Marcos regime. “What drove me forward in that pretty dangerous situation wasn’t bravery. It was ego,” he says. “I wanted a ringside seat to the whole thing. I wanted the story.”

But by the end of the regime, he was done with chasing news. “Like an idiot, I decided I was going to start a novel,” he says. In his office at the UW in the late 1980s, he would file a story for The Monitor and then turn to the painstaking work of writing his first novel, “Cebu.” “It was so much harder than writing a news story,” he says. “Every word counted.”

Peter Bacho’s new book, “Uncle Rico’s Encore: Mostly True Stories of Filipino Seattle,” is seen by UW American Ethnic Studies professor Rick Bonus as a major contribution to the canon of Northwest storytelling.

When the book was ready, he presumed he wouldn’t have luck with a big publisher. “They probably wouldn’t be interested in a book about Filipino Americans,” he says. He focused instead on the UW Press, which had a record with Asian American authors and had found great success with the republication of John Okada’s “No-No Boy,” a critically acclaimed novel that features the Japanese American experience.

By the time “Cebu” was published, Bacho was working as an attorney in San Francisco. “I was very comfortable at the UW, but I wondered did I leave law too soon,” he says. “So I gave law a couple of years before I decided to go back to writing.”

One day, while still in California, he got a call from the UW Press that “Cebu” had won the American Book Award. Bacho hadn’t known he was in consideration. He was pleased, his parents were thrilled. “My dad had been disappointed I had given up law, but now he was very proud,” he says. He would carry copies of “Cebu” with him and encourage everyone he met to buy one. His father even peddled them at a funeral, much to his mother’s chagrin.

Bacho eventually moved back to Washington and wrote several more “good books that nobody read,” he says. And he joined the faculty of The Evergreen State College and lectured at UW Tacoma. When he finished his young adult novel, “Leaving Yesler,” in 2010, he decided to take a break from writing. But then, on his 68th birthday, he picked up a pen. He wrote a story about his 18th birthday in 1968, the day he tried to enlist during the Vietnam War, thinking he would soon flunk out of college anyway. “I really liked the way the story turned out,” he says. “And one good story leads to other good stories leads to other good stories. And you have a collection.”

Another of these good stories focuses on José Rizal Park on Beacon Hill. From there, visitors can see the buildings of downtown, the Puget Sound and the Olympic Mountains. But for many Seattleites this is a new angle, from the south, from a lesser-known city park perched over a tangle of roads and overpasses where Interstate 5 and Interstate 90 meet.

It’s Seattle in all its glory viewed from a park named for a writer, a national hero of the Philippines. It’s a symbol of the deep connection a generation of Filipino immigrants felt for their homeland and their new city. “My Uncle Vic and Trinidad Rojo fought to make this park in the 1970s,” Bacho says. They wanted to draw respect and attention to their community, which had helped build Seattle.

As he stepped from his car for a portrait shoot one rainy afternoon this winter, Bacho turned and took in the panorama. He pointed to the Chinatown-International District, where he would meet his Uncle Vic for lunch, the neighborhoods he roamed as a child—the landscape where he developed his identity and drew inspiration. And then he looked at the park and nodded. “This is the right place.”