In the days before Nintendo or Xbox, young boys spent hours hovered over electric football sets, the kitschy ’60s board game that used a vibrating metal field to send miniature plastic players crisscrossing to pay dirt.

Tyrone Willingham never turned his on. “I would just sit there going through formations and manipulating things on the field,” he recalls. “Sometimes you don’t know your destiny, but then you start looking at things and say, ‘Maybe this is what I’m supposed to do.’ ”

Willingham’s destiny has taken him from his North Carolina roots to the playing fields of Lansing, Palo Alto and South Bend. Along the way he became a pioneer for African Americans hoping to coach college football, as he headed teams at Stanford and Notre Dame. Now Willingham is the University of Washington’s new football coach, where he will have to lead nearly 100 student-athletes in a program that just finished the worst season in its 115-year history.

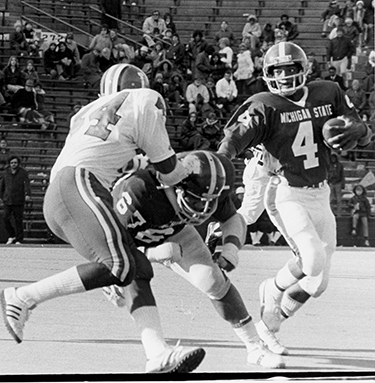

Willingham played quarterback and wide receiver at Michigan State.

The turnaround is just one more challenge for Willingham, who’s faced a life of overcoming the impossible. During the Civil Rights era, he was among the first African Americans to integrate his hometown school. He was the first black quarterback to start for his high school football team. Later he had to prove himself as a walk-on at Big 10 power Michigan State. During 15 years as an assistant coach, he wondered if he would ever achieve the goal of coaching his own team.

But there has been plenty of glory, too. His peers twice honored Willingham as the Pac-10 Coach of the Year (1995 and 1999). He was named Sporting News Sportsman of the Year in 2002, and when Sports Illustrated listed its most influential people of color in sports, Willingham’s name was in the top 10. After he was fired by Notre Dame, Newsweek’s popular “Conventional Wisdom” column gave the school a “down arrow.”

Others may focus on awards and accolades as levels of achievement, but Willingham draws on his inner strengths, not his résumé, to motivate his teams. “What everyone needs is a better mousetrap,” he says, carrying the taut body of a man two decades younger and seated drill-sergeant-straight behind his desk in a still-barren office in the Graves Building. “If you give me a better mousetrap, I’ll buy it. If you teach me how to do what I need to do better, I’ll listen. I’ll invest in you just as you are investing in me.”

“Let’s be champions. Let’s have great students. Let’s be great people. And let’s have a lot of fun in the process.”

Tyrone Willingham

And that is what Willingham, 51, overachieving since his days as a 5-foot-7 and 140-pound high school quarterback, told his new players after being named to replace former UW Coach Keith Gilbertson. “Let’s be champions. Let’s have great students. Let’s be great people. And let’s have a lot of fun in the process.”

“When you identify those four things,” he says, “I think that’s what every kid wants. I can provide the right example for them and help them create that model.” So when UW President Mark Emmert assembled the profile of what his next football coach should have — integrity, character, discipline, excellence and loyalty — one of the top candidates wasn’t available. Tyrone Willingham was wrapping up his third season as head coach at the University of Notre Dame, finishing the 2004 season 6-5 and preparing for a second bowl game in three years. Then, on Nov. 30, Willingham was fired. “When we began our search, if you had told me Tyrone would be available, I never would have believed you,” says UW Athletics Director Todd Turner.

Rev. Edward Malloy, Notre Dame’s outgoing president, took the unusual step of publicly criticizing his school’s firing of Willingham. He thinks Washington made a good hire, recalling Willingham as a man of few words who tends to speak from the heart.

“Tyrone is a straightforward and self-possessed man who sees himself as a teacher and a character-builder,” Malloy says. “Working in a college environment is perfect for him. He’s the kind of person that people in the academy can relate to and be inspired by.” Those inspirations are already working. The day after learning Willingham would be his new coach, UW quarterback Isaiah Stanback had already bought into the Willingham plan. “There are things he can teach me about football,” said the sophomore, who will battle for a wide-open quarterback position when spring practice opens next month. “But there are also things he can teach me about life.”

***

Willingham had the best teachers possible for life’s lessons: his parents, Nathaniel and Lillian Willingham, who raised four children during the sixties in a racially charged South. She earned a master’s degree in education from Columbia University and he left school after the fifth grade, but despite their differing backgrounds “they really were married until, truly, death took them apart,” recalls Willingham.

Lillian was an elementary school teacher for more than 30 years, while Nathaniel was a property owner and landlord who, even into his eighties, never shied away from a hard day of work.

“What my parents taught me,” Willingham says, “requires just one word to explain. Everything. They were the best coaches I’ve ever been around. They were the best people that I’ve ever been around. They were very different, but they had core values that were very much alike.

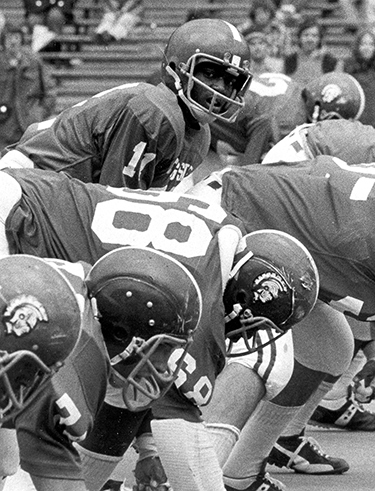

Willingham during his playing days at Michigan State.

“They taught me to respect myself, to respect others, that hard work and being a team player were important. They believed in education and having a spiritual component to your life. They understood others, but they also knew how to balance the ups and downs of life.”

The Willinghams were prominent members of the African American community in Jacksonville, N.C., a small community adjacent to the Camp Lejeune Marine Corps Base. Tyrone attended the segregated Georgetown High School, which covered all classes from first grade to senior year of high school. With no community center in the neighborhood, Nathaniel and Lillian offered the basement of their home as a gathering place for children.

“My parents sacrificed not just for their kids, but also for the betterment of our community,” Willingham recalls. “They truly believed in the greater good. This was not about self, but about the community, our country and this world.” Nathaniel gave away vegetables from his garden, trained himself to be a contractor and built the local Masonic lodge. Lillian was such a local fixture that she has been memorialized with a park, as well as the L.P. Willingham Parkway, which was developed as part of a neighborhood renaissance.

Together they infused in their children an unconditional belief in God and in the notion that people should not be judged by the color of their skin. But Jim Crow tried to trump that belief. Even though a white school was within walking distance of the Willingham home, Tyrone and his siblings were bused to the all-black school. It was at that school in May 1966 — at the end of fifth grade — that Tyrone Willingham’s world changed dramatically. On the morning of Georgetown’s graduation ceremony an explosion destroyed the gymnasium that would have housed the festivities. Some speculated it was a bomb. Others said it might have been an accident caused by the school’s boiler system.

“The powers that be never really told us what happened,” says Willingham. “All we knew was that there was no more Georgetown High School, and the next school year we had full-scale integration.”

Later that fall Willingham watched a football player on television that would be the catalyst for his own career, a black athlete from Fayetteville, N.C., named Jimmy Raye. The game was a match-up of the nation’s top two teams — Michigan State against Notre Dame — and to this day it is regarded as one of the greatest college games of the 20th century. Raye started at quarterback for Michigan State and forged to a 10-0 lead, but the teams were so evenly matched, the game ended in a 10-10 tie.

“It was a significant moment in my life,” Willingham says, “although I didn’t know it at the time.”

Suddenly the boy who used his electric football game as a three-dimensional playbook was taking his interests to the playing field. By the time he got to high school, Willingham was one of Jacksonville High’s top athletes — captain and most valuable player of the football, baseball and basketball teams his senior year.

Off the radar screen of recruiters at larger universities, Willingham handwrote letters to more than 100 college football teams, highlighting his abilities and trying to gauge their interest. Two schools replied: the University of Toledo and Michigan State.

“Jimmy Raye was an assistant coach at Michigan State at the time,” Willingham recalls, “and as a North Carolina guy, he was the conduit that allowed me to walk on there.”

“My parents always instilled an element of challenge in us, to not be afraid of challenges and to be able to take a risk.”

Tyrone Willingham

In 1973, Willingham started four games at quarterback as a freshman for the Spartans, completing 10 passes and earning a scholarship for his sophomore season. But he never completed another pass the rest of his college career. He earned three letters each in football and baseball (he played centerfield and received All-Big Ten honors) and graduated with a degree in physical education.

Stuck on the sidelines, Willingham often signaled in the plays. It provided a glance into the pressures and responsibilities of the job and made him contemplate coaching as a profession.

“My parents always instilled an element of challenge in us, to not be afraid of challenges and to be able to take a risk,” he says. “I don’t know if coaching provided that to me at first, but once I got the chance to see what our coaches at Michigan State had to face, I thought, ‘Oh, that’s a job that’s demanding mentally and physically. It’s everything I want and it’s a worthy profession.’ ”

After just four months as a graduate assistant under Michigan State Coach Darryl Rogers, Central Michigan hired Willingham as an assistant. In 1980 he returned to the Spartans as secondary and special teams coach and made the most important decision of his life — he married his sweetheart Kim, whom he had met at a Michigan State basketball game. During the next decade, the Willinghams followed coaching jobs to North Carolina State, Rice and Stanford and welcomed daughters Cassidy (born in 1984) and Kelsey (1988), and son Nathaniel (1990).

As a Stanford assistant, Willingham shaped his coaching style under its head coach Denny Green. “When you were around Denny Green,” he remembers, “even the janitor knew what the vision was and knew how he could help that vision. If only a few people know the vision, then your organization is never in full gear to accomplish that vision.

“If you can show young men how to be a better football team, I think they’ll follow. If you can’t show them how to do that, they have no value for you.”

Willingham followed when Green was hired to coach the Minnesota Vikings in 1992. As running backs coach, he helped the Vikings make the playoffs in three straight seasons.

But by 1995, legendary Stanford Coach Bill Walsh, who had succeeded Green, resigned. Wanting to put discipline back into the program, Athletics Director Ted Leland looked no further than Stanford’s former assistant coach.

Willingham had finally reached the top level of coaching. But today he bristles when asked if he felt he had “arrived.”

“I hope I never arrive,” he says. “I hope that never becomes part of my make-up. No player is greater than the team. No coach is greater than the team. If we had more people with that same thought process, I think we’d have a better world.”

***

Willingham paid immediate dividends at Stanford. Picked in 1995 to finish last in the Pac-10, the Cardinal went 7-4-1. By 2001, the team was a contender, winning nine games for only the second time in a half-century and playing in its first Rose Bowl in 29 years. Darrin Nelson, Stanford’s senior associate athletic director and a running back for the Vikings during Willingham’s tenure in Minnesota, credits organizational and personal skills for Willingham’s success.

“Tyrone has a system that always works for him,” Nelson says. “He never seems to lose control of what he’s doing. He’s low-key, a behind-the-scenes guy without always being behind-the-scenes. I found that parents were comfortable with Tyrone. He looks like a college professor, and he has a general interest in his athletes graduating.” And they did. Stanford graduated 83 percent of its players in 2001, fourth among Division 1 institutions, a quality that wasn’t lost on Notre Dame when it was looking for a new coach the following year. After initial choice George O’Leary was found to have stretched the truth on his résumé, Notre Dame came after Willingham.

“I was sitting comfortably at Stanford,” he says, “and we had a chance to make that one of the better programs in the country. But I thought that being an African American coach at Notre Dame would put me in a spotlight that would help other (black coaches) achieve the same. If we were successful at Notre Dame, I could help a lot of people.” Willingham’s success with the Fighting Irish — 21-15 in three seasons — has been debated since Notre Dame’s Athletics Director Kevin White announced his firing. Even White can’t hide his fondness for the coach he let go.

“Tyrone is a natural leader who clearly directs all activity by example,” he says. “He is terribly empathetic, certainly task-oriented, adaptable and incredibly passionate about teaching both the game and life lessons to young men.”

“Tyrone is a natural leader who clearly directs all activity by example,” he says. “He is terribly empathetic, certainly task-oriented, adaptable and incredibly passionate about teaching both the game and life lessons to young men.”

But while colleagues and pundits were saying Willingham got a raw deal, the coach took the news in stride.

“Everything that happens in your life is a positive if you turn it in that direction,” he says. “I don’t feel guilty in saying that I’ve never had a bad day. When Notre Dame fired me, that wasn’t a bad day, it was a bad moment. I went home to a wonderful family who still loved me and cared for me. I still had a wonderful life. I refused to let that be a bad day.

“Certainly on Saturday afternoons I’ve had three hours of bad moments. But three hours are still not greater than the next 21 that comprise that day. And if you let it become a bad day, it’s your fault.”

Willingham considered taking a year away from coaching, which would have eliminated one of the four things he holds most dearly: football, family, golf (he carries a 12 handicap) and God — “although not in that order,” he says. But Turner called soon after the firing, and the thought of returning to the West Coast and to a conference in which he was familiar intrigued Willingham.

When he was introduced as the next UW head football coach on Dec. 13, signing a five-year contract worth $1.4 million per year with $600,000 in possible incentives, Willingham said his family was excited to make Seattle its new home. “My son would have walked here. He had already changed the wallpaper on his computer to purple and gold,” he recalls.

Willingham, teamed with Husky Men’s Basketball Coach Lorenzo Romar, makes UW the only Division 1-A school in the U.S. with African Americans in its two most prominent coaching posts. There are only two other African American football coaches in Division 1-A and Willingham is the only black football coach ever to be given a second chance at that level. “The numbers speak for themselves,” he says.

When asked what it is like to be a spokesman for African Americans, he says it is a “mixed blessing. I think we as individuals should be extremely proud of our ethnic backgrounds. Whether it’s Italian, whether it’s African American, we should be proud of that. So I am proud to be African American. But at the same time we want to get to the point in our culture where that is not the focus, where it’s really the body of work that a man does.”

Willingham prefers to focus on the type of team Husky fans can expect under his leadership. “I know how casual football can be on the West Coast,” he says, “but this is not one of those places. It is time for the University of Washington to return to being “the Dawgs.” In this program, that is a vicious animal. And I think our players are excited about that.”

“He is going to have a tough, disciplined and smart football team,” says Stanford’s Darrin Nelson. “The Pac-10 just got a lot more difficult.”

Willingham has dubbed the new revolution of UW football as a “joint venture,” calling on the entire Husky family to make an investment into the program. “This family has to unite to do all the things to put this program back to where it was. The excitement has to be generated by all of us who want to build a program for a long period of time.” That program will be built on the traits Emmert and Turner targeted: integrity, character and excellence. But also on intelligence, an attribute that Willingham calls the most essential.

“If I have a plumber come to my house,” he says, “please Lord, send me the smart plumber. If I have a football player in our system, please send me the smart football player.

“There’s nothing cooler than being smart, and we have to emphasize that to our athletes and to our children. It’s not just on the field or in the classroom. It’s life.”