Plugged in Plugged in Plugged in: UW experiments with laptop computers for 65 freshmen

An ambitious experiment integrates the computer into undergraduate education.

An ambitious experiment integrates the computer into undergraduate education.

When I left for MIT in 1967, my parents equipped me with state of the art equipment—a manual typewriter and a bamboo slide rule.

But when my son Ben goes to college in 2002 (I hope), he will take a computer.

His computer will not be simply a faster typewriter or a more accurate slide rule. It will give him access to information worldwide; enable him to send messages to teachers or classmates (and perhaps even his parents) day or night; and turn him into a publisher of his own information, a latter-day William Randolph Hearst.

Unlike my slide rule or typewriter, Ben’s computer may revolutionize higher education. No longer passive notetakers, students may become active learners—acquiring knowledge by interpreting it, using it in context and communicating it to others.

While many universities are rewiring their campuses for high speed data, and some even are requiring students to own computers, few are studying how the computer revolution will change learning. Even my alma mater, MIT, which has been a leader in bringing computers to students, admits to knowing very little about the computer’s effect on higher education.

At the University of Washington, undergraduate students are starting to get plugged in. More than a year ago, the UW embarked on UWired, an ambitious experiment that integrates the computer into undergraduate education. The result was the birth of a new way of learning—an electronic community that saw students take over more responsibility to teach themselves and their colleagues.

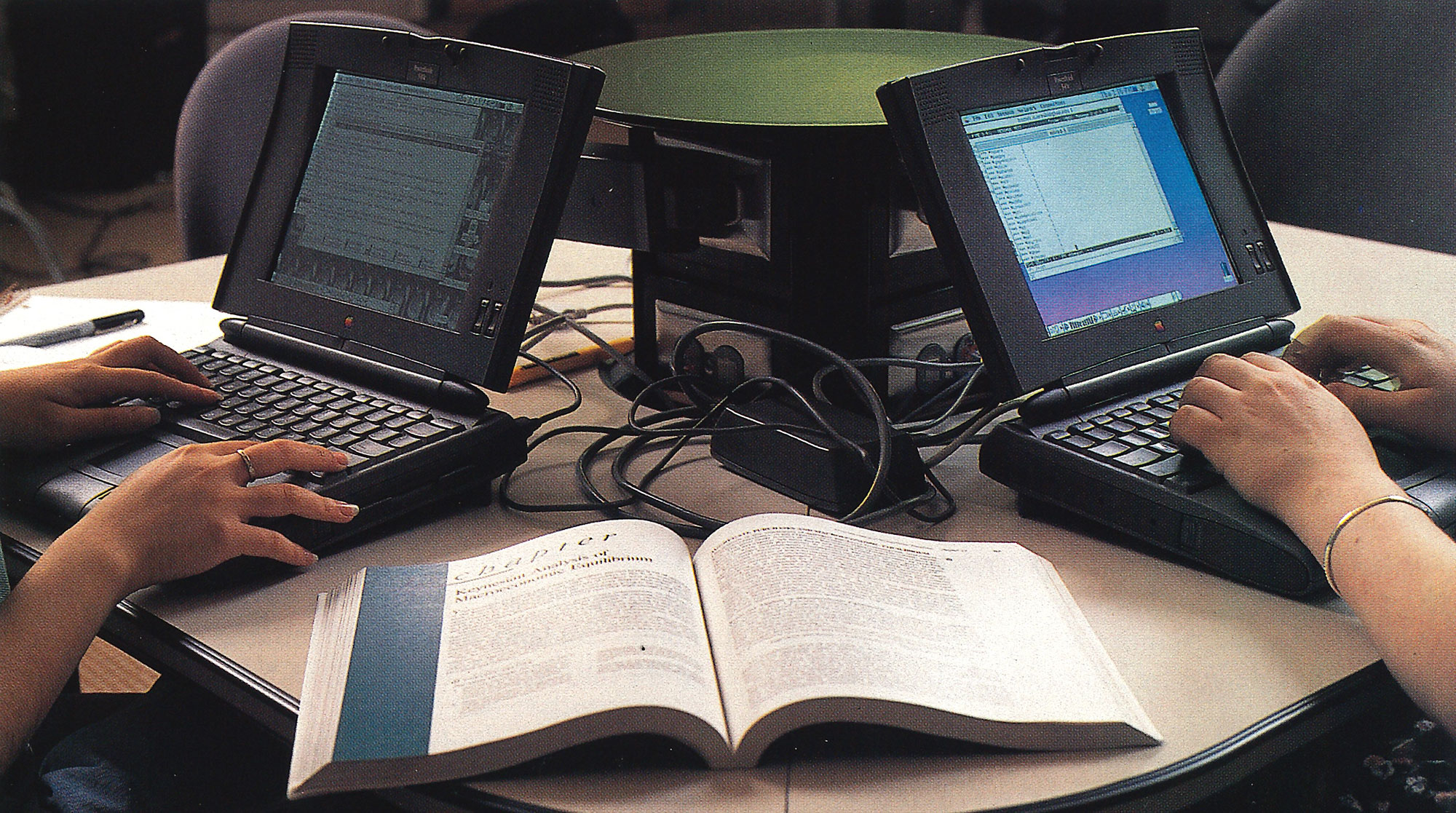

Karen Thompson (left) and Mandy Hau use their laptops in the UW’s innovative Collaboratory.

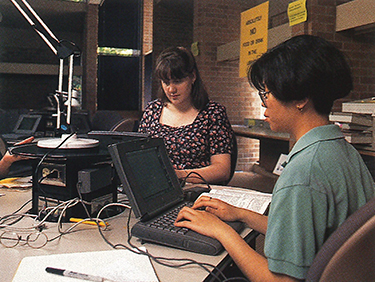

The experiment started when former UW Provost Wayne Clough, now president of Georgia Tech, put together a team to integrate computing into the undergraduate experience. The UWired team—composed of instructional specialists, computer experts and librarians—recruited a small group of faculty and teaching assistants interested in the project. Each were given an Apple PowerBook 540C laptop computer for the year.

The team then recruited students during freshman orientation and other events. These students all had to be members of a Freshman Interest Group (FIG), a small group that has shared interests and activities such as freshmen interested in international studies. Each group has 20 to 25 students who take the same classes during their first quarter.

Three of these freshman groups became “UWired FIGs.” In addition to their normal classes (taught by faculty who had participated in the summer UWired seminar), the students attended a special information and technology seminar, taught by UW librarians.

Amee Epler signed up for UWired partly because “it sounded cool,” and partly because it offered her small classes. Mandy Hau enrolled in UWired more or less by accident. “I didn’t know what it was about until I got my computer. But then I was really happy I had chosen it,” she says. As with many other students, she found the computer a great way to communicate with classmates and instructors, as well as getting access to high-quality printers for written projects.

Hau, along with the other UWired students, created a “Home Page” on the Internet—basically, an electronic document telling a little about her and her interests (hers contains a brief digital recording in English and Cantonese).

Although the document is potentially available to millions of individuals worldwide, since it has been published electronically, Hau regards it as no big deal. “It’s not as if I wrote a book,” she says. But the ease with which she has become a publisher has sensitized her to how easy it is to create information and misinformation on the Internet. “I’d trust official information from a university or department, but I know there are a lot of weirdos out there (on the Internet).”

As the quarter progressed, UWired students thrived on the small-group interaction. “In a lot of projects, we used the information together,” says UWired student Beth Frymeier. “I learned most of my `how to’ information from other students in the class. They became some of my best friends.” Adds UWired student Karen Thompson, “It was a great way to adjust in fall quarter. And having the computer was helpful in all my classes.”

Small group interaction was fostered by a specially constructed room in Odegaard Undergraduate Library, the Collaboratory, where many UWired classes were held. The room has a series of pods, or work areas, clustered around a utility pole. While students could swivel around and hear a lecture, the room was designed specifically for students to share information with one another, to converse—and to collaborate.

These conversations took place mainly via electronic mail. E-mail is one of the simplest tools for students to use, but also one of the most powerful, according to Kirk Branch, a UWired instructor and a TA in English.

E-mail is one of the simplest tools for students to use, but also one of the most powerful.

“E-mail provided a kind of written conversation. As a result students wrote more, and some who were inhibited in class turned to e-mail as their preferred form of communication. As a group, the students became more active readers. You could see the points moving from e-mail discussions into their more formal papers, as they developed ideas by conversing with others,” Branch says.

Jim Green, who teaches Anthropology 100, divided his UWired students into teams of two or three and had them create a newsletter on subjects discussed in the course, including topics that have been in public debate, such as human evolution. They were encouraged to scour the Internet for information and graphics to incorporate in their stories. Students analyzed and critiqued the information they found, to determine if it was biased or inaccurate. Their classmates also was critiqued their work.

“The students learned cooperatively. In fact, they voluntarily took over some of the teaching responsibilities from us on explaining techniques for acquiring electronic information,” Green says. “I was impressed with the students’ willingness to teach others. It gave some of the students a chance to be important among their peers and helped to create a self-motivated learning community.”

Instructors’ responses to the UWired experience have ranged from “evangelical to merely enthusiastic,” according to Louis Fox, associate vice provost for undergraduate education. “Initially, we all focused on the lovely Apple 540c [laptop], but that was the tip of the iceberg. We’ve learned that issues of training, of instructional support, technical support and facilities are inseparable from implementing new technology in the instructional program.” The melding of expertise in computers, information and education has been one of the project’s strengths. This kind of collaboration, Fox believes, is absolutely essential for projects such as UWired to succeed.

Theresa Mudrock, one of the librarians involved with UWired, says she was impressed with the power of e-mail. “Students in UWired were much more likely to contact faculty and to speak more freely. I saw them coming together more as a group to comment on things—not just material in the class, but the way the class was organized,” she notes. “Students also learned about the potential biases in the information they read, and the necessity for being selective.”

While students, faculty and administrators celebrate the experiment’s initial success, there is a huge potential bug in the program. How can the University satisfy the rapidly expanding need for access to computer services and computing power? The campus use of e-mail, for example, is growing explosively. The number of UW e-mail accounts grew from less than 12,000 in 1987 to more than 52,000 in 1995. With ever-increasing demand, the University may have a hard time maintaining the level of service it has now.

Another potential glitch is the role of computing equipment in the classroom, an issue brought to the fore by UWired. Half of the UWired computers in the pilot phase were donated by Apple. The retail price of a fully equipped PowerBook is over $4,000.

It is not feasible financially for the University to provide similar equipment free to the entire freshman class. To cover all 3,000 freshmen could cost more than $12 million.

But if UWired is such a success, how does the UW extend its benefits to a larger group of students? The answer, at least for now, is incremental growth. The UWired freshman project grew from about 65 students last year to 1,300 this fall. However, only 65 of this year’s freshmen got laptops. The rest are using a new facility, built next to the Collaboratory, which houses 30 stationary, desktop computers.

About 250 students are in one of nine “intensive” UWired groups, taking a two-credit class Autumn Quarter that stresses computer skills. The remainder have a less-intensive, one-hour skills class, which uses peer instructors. As with the first year of UWired, the results of the program will be scrutinized carefully.

Meanwhile, the UWired team is offering more training to faculty on the use of computers in a learning environment. In addition, UWired is supporting more than a dozen projects in junior- and senior-level courses. The instructors will receive training from the UWired team, access to the Collaboratory and some funds for software. The classes approved in this first round include “Computer Assisted Journalism,” “Computer Reconstruction of Brain Structures” and “Topics in Advanced Composition.”

The remodeling under way in Mary Gates Hall (the old Physics Building) also will merge technology into higher education. The facility will include rooms for training faculty in the uses of technology, as well as “project rooms,” small conference-size rooms with computer workstations. And Collaboratory-like rooms will be built, in several different styles.

The UWired team began their efforts more than a year ago with great enthusiasm. Much of that enthusiasm remains. But it is tempered now with the experience of actually working with faculty and students to design cost-effective methods of helping both groups enter the digital world. Given the complexity of that challenge, it is not surprising that the team adopted the following motto:

Nil facile.

Nothing is easy.

UW students are not the only group who can cruise through computer information sources, such as the World Wide Web. UW alumni now have a host of services at their fingertips—including an on-line version of Columns magazine that has more to it than the printed version.

If you already have a computer account and can use web “browsers” such as Netscape or Mosaic, you are ready to “surf” the UW’s space on the Internet. Begin with the University of Washington Home Page, which has an “almost live” picture of Suzzallo Library, Rainier Vista and “Red Square.” The web address is http://www.washington.edu.

Information directly related to UW alumni can be found on the UW Alumni Association Home Page, which includes a comprehensive list of events, links to career services information and even an e-mail form to update your street address. The UW Alumni Association Home Page can be found at http://www.washington.edu/alumni.