Powerful prose Powerful prose Powerful prose

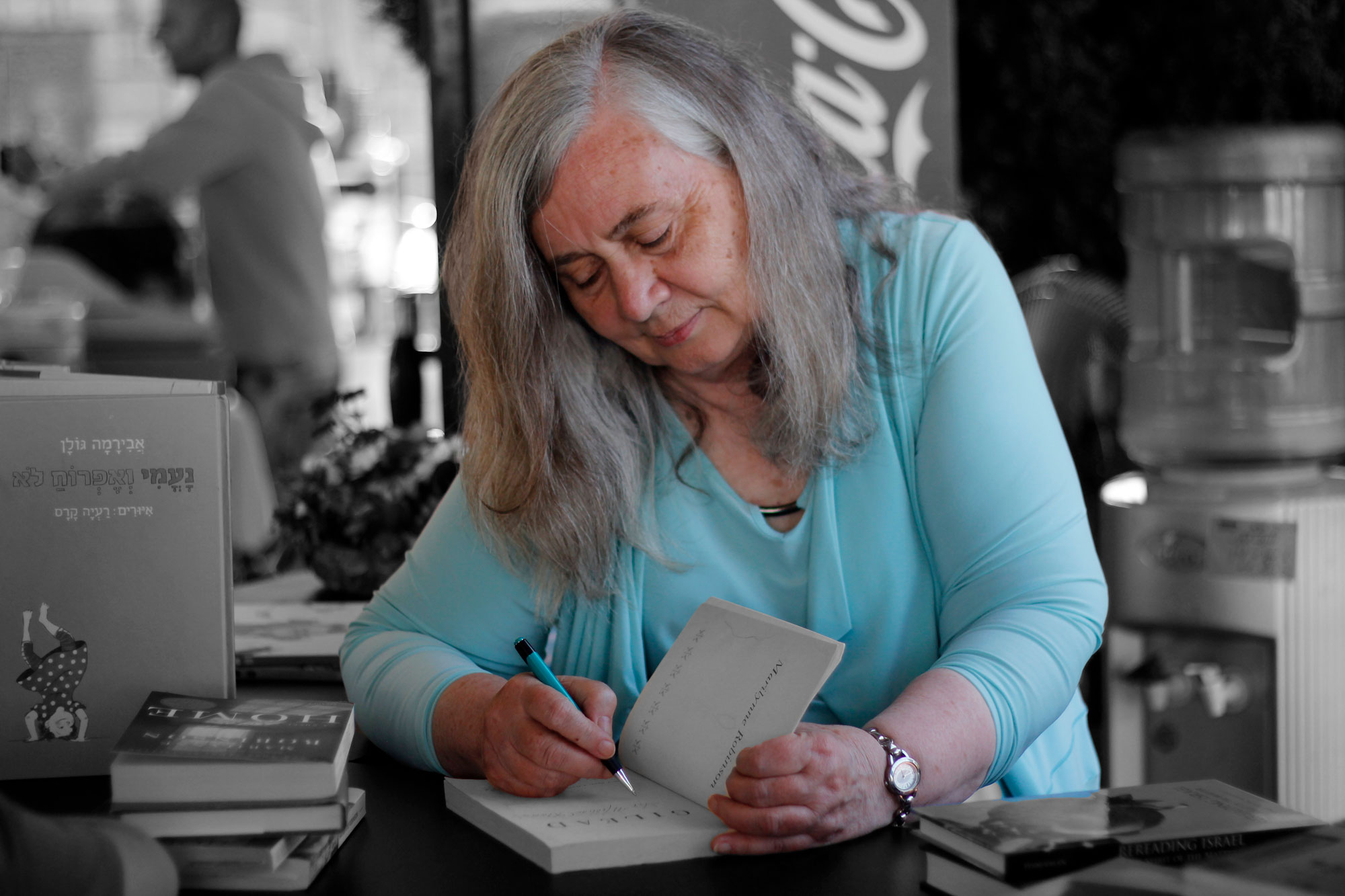

Northwest connections played a big part in Marilynne Robinson’s life. The renowned author is this year’s recipient of the UW’s highest alumni honor.

Northwest connections played a big part in Marilynne Robinson’s life. The renowned author is this year’s recipient of the UW’s highest alumni honor.

Read Marilynne Robinson’s remarks upon receiving the Alumna Summa Laude Dignata Award on June 8, 2023.

Early in the novel “Gilead,” the narrator, the Rev. John Ames, confides: “For me writing has always felt like praying ... You feel you are with someone. I feel I am with you now. …”

That’s one of the great gifts of Ames’ creator, Marilynne Robinson, too: the ability to make her readers feel that she is not only with us, but part of us.

Since Robinson earned her Ph.D. at the UW in 1977, she has become one of the world’s premier fiction writers. A Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Critics Circle Award and the Library of Congress Award for Fiction are among her many honors. Yet fiction is just one facet of Robinson’s work. She teaches, writes nonfiction books and essays, and is an esteemed contributor to public discourse on ideas and events. In 2016, Time magazine named her one of its 100 Most Influential People.

This year, the UW will present Robinson with the Alumna Summa Laude Dignata Award, the highest honor bestowed upon a graduate for exceptional lifetime achievement. Past recipients include former Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell, ’78; architect Steven Holl, ’71; former Washington Gov. Daniel Evans, ’48, ’49; and children’s book author Beverly Cleary, ’39.

“When you are looking at significant American literary artists right now, she has to be way up your list.”

Professor Charles LaPorte

Speaking by phone from her home in Saratoga Springs, New York, Robinson says she is eager to revisit her alma mater. “I loved living in Seattle. … A great deal went on for me at UW. I had my first child there and so on.”

That casual “and so on,” includes writing the initial stages of her first novel, “Housekeeping,” while she completed her Ph.D. And now, in the English Department within the College of Arts & Sciences where Robinson was once a student, her books are a staple of the curriculum. “When you are looking at significant American literary artists right now, she has to be way up your list,” says Professor Charles LaPorte. “She is in a very rare company of people who are making a difference—but not just making a difference as artists. She is a philosopher, too: someone who appeals to people who think.”

Robinson’s fame increased exponentially in 2016 when President Obama, on a visit to Iowa, made an extraordinary request: He wanted to record a conversation with Robinson. (Has a sitting president ever interviewed a novelist before?) It turns out Obama had read “Gilead” on the campaign trail and was smitten. He posted it on Facebook as one of his favorite books, along with the Bible and The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln. Obama and Robinson first met in 2013 when he presented her with the National Humanities Medal in conjunction with the National Endowment for the Humanities. He told her, “Your writing has fundamentally changed me.”

Robinson started her first novel, “Housekeeping,” while she was working on her Ph.D. in the 1970s. It was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in fiction in 1982.

Their later conversation, recorded and transcribed in two issues of The New York Review of Books, serves as a testament to the profound impact Robinson’s writing has on readers around the globe, as well as to the wide-ranging intellect of our former president.

Besides, it was fun. “That was one of the pleasantest experiences of my life,” Robinson says. “It was pleasant and very exciting at the same time, which is not always a combination you can rely on happening, you know.” Because she had already met the president, Robinson didn’t feel intimidated. “I’d had a certain amount of contact with him before that. I had had dinner at the White House, and I had exchanged letters with him. And I knew he really is a very gracious man, which is obvious in everything he does, and I just knew I could trust him to make me feel it was a totally good experience. And he did.”

Their discussion touched on the strains in American democracy and the difficulties of living up to the doctrines of Christianity. They talked about the musical “Hamilton,” about empathy and optimism, and the role literature can play in a world that runs on tweets and seems to have lost its attention span. Robinson told Obama about how the narrative voice of her character, the Rev. John Ames, “just showed up” one day as she was sitting with pen and paper in a hotel room in Massachusetts—and what a surprise it was to be suddenly writing from a male point of view. At one point, Robinson suggested that the word “competition” should be struck from the American vocabulary and Obama quipped: “Now, you’re talking to a guy who likes to play basketball and has been known to be a little competitive. But go ahead.”

Robinson was born Marilynne Summers in Sandpoint, Idaho, in 1943. She grew up in Coeur d’Alene, where her father worked in the timber industry and her mother stayed home to raise Robinson and her brother, David. The Presbyterian Church and poetry were in the fabric of Robinson’s life. As a child, her brother (now a professor emeritus of art history) predicted that he would become a painter and she would be a poet. In high school, Robinson seemed headed in that direction. She wrote Edgar Allan Poe-inspired verse and translated a section of “The Aeneid” from Latin. Eventually, she gave up writing poetry for scholarship.

As an undergraduate at Pembroke (now Brown), Robinson took three years of creative writing classes before coming to the UW to pursue her master’s in 1966. She took courses in American literature as well as delving into Chaucer, Victorian literature and Shakespeare to broaden her literary background. She continued her Shakespeare studies when she was accepted into the Ph.D. program within the College of Arts & Sciences in 1973.

Robinson’s dissertation, “A New Look at Henry VI, Part II: Sources, Structure and Meaning,” involved extensive research in primary documents and long hours combing through microfiche at Suzzallo Library. She focused her analysis on an underappreciated play and showed it to be “more accomplished, subtler, more coherent than has been suspected …” Her dissertation committee also noted that even though Robinson used standard methods of literary criticism, “what is unusual here is not only the play to which she applies them, but the sensitivity with which she has used them to arrive at an excellently written and most perceptive dissertation.” Her adviser, Professor Bill Matchett (1923-2021), a few years before his death still vividly recalled his former student. He needed just one word to describe her: “Brilliant.”

“I am always writing fiction and nonfiction at the same time—a habit I formed in Seattle—and I find they stimulate each other, they keep each other in focus, so they don’t really compete.”

Marilynne Robinson

While attending the UW, Robinson married Fred Robinson and had her first son. (They would have another son and later divorce.) At the same time she was starting a family and immersed in the high-pressure research and writing of her dissertation, Robinson had the capacity to begin another writing project, experimenting with metaphor, drafting the initial stages of what would later grow into a novel.

“I guess she was a little bored,” jokes poet, author and teaching professor Frances McCue, who uses Robinson’s work in her classes. She finds the idea of Robinson writing her dissertation and working on a novel at the same time hilarious, a feat your garden-variety Ph.D. candidate would likely consider superhuman.

Robinson laughs at the notion. “I’m one of those students who took her time in graduate school. But I am always writing fiction and nonfiction at the same time—a habit I formed in Seattle—and I find they stimulate each other, they keep each other in focus, so they don’t really compete.”

After completing her degree, Robinson began shaping her initial notes into a novel, without really looking beyond that. “I had no thought of publishing it. I thought it was unpublishable,” she recalls. Why? “Too poetic.” Nevertheless, she shared her manuscript with a friend, who sent it to his agent, and the next thing Robinson knew she had a book contract. “Housekeeping” was published in 1980.

In language of heart-stopping sensuality, the story braids the lives of three generations of women in one family. It opens with the description of a legendary disaster in a fictional Idaho town. As a night train crosses a bridge, it suddenly “nosed over toward the lake and then the rest of the train slid after it into the water like a weasel sliding off a rock.” That train sprawled at the bottom of the lake and the passengers entombed in it haunt the town and its inhabitants. Like a Greek tragedy, the disaster ripples through generations.

“Here’s a first novel that sounds as if the author has been treasuring it up all her life, waiting for it to form itself,” Anatole Broyard wrote in The New York Times.

“It’s as if, in writing it, she broke through the ordinary human condition with all its dissatisfactions and achieved a kind of transfiguration. You can feel in the book a gathering voluptuous release of confidence, a delighted surprise at the unexpected capacities of language, a close, careful fondness for people that we thought only saints felt.”

After that awestruck early review, “Housekeeping” received the PEN/Hemingway Award for best first novel and then, in 1987, was adapted into a movie. “Housekeeping” has since been named by the Guardian Unlimited as one of the 100 greatest novels of all time.

A quintessentially Northwest story, “Housekeeping” is set in a town hugged by mountains and bounded by a deep ancient lake, much like the landscape of Sandpoint, where Robinson was born. And that setting—the remote town, the deep, cold lake whose waters permeate the atmosphere—is as fundamental to the story as any of its characters. The place seems to hold the people who live there in thrall, as trapped as those passengers on the train.

The Northwest connection is significant to LaPorte, the UW professor, for several reasons. When teaching incoming English majors at the College of Arts & Sciences, he likes to give them a little department history. “I knock myself out to tell my students when we are doing Theodore Roethke or Elizabeth Bishop that they taught here. Or Richard Hugo or James Wright or Carolyn Kizer: They all came out of this program. They came here to work with us.”

And now there is Robinson, too.

Surprisingly, after her initial success with “Housekeeping,” Robinson put away fiction writing for more than two decades and turned her attention to research, scholarly writing and teaching. In 1989 she published her first nonfiction book, “Mother Country: Britain, the Welfare State, and Nuclear Pollution” and in 1991 was offered a teaching post at the Iowa Writers Workshop, the famed MFA program at the University of Iowa. She retired in 2016.

It wasn’t until 2004 that Robinson re-emerged as a novelist with the publication of “Gilead.” The aged narrator Ames, who has lived his entire life in the small town of Gilead, Iowa, is writing down his life story for his young son. Kirkus Reviews called “Gilead” “a novel as big as a nation, as quiet as thought, and moving as prayer. Matchless and towering.” The Pulitzer Prize and the huge rush of acclaim that followed seemed to place Robinson at the pinnacle of an amazing career. But she was just warming up.

The story of “Gilead” and Ames grew into a series with the publication of “Home” (2008), “Lila” (2014) and “Jack” (2020). In each of those novels, Robinson retells the events of “Gilead” from the perspective of a different character—and the awards continued to pile up: a second National Book Critics Award and The Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction.

It’s easy to see what drew President Obama to “Gilead.” Ames is a man who thinks continually about his place in life as a son, grandson, father, husband, friend and, perhaps most urgently, about his service as a minister and role model to his community. As Ames looks back at the accumulation of sermons he wrote over the years, he reminisces, “I wrote almost all of it in the deepest hope and conviction. Sifting my thoughts and choosing my words. Trying to say what was true. …” One can easily imagine Obama writing those same sentences about his many speeches and his books. And it seems that Robinson is speaking from her own heart, too, as she writes in the thoughtful voice of the character who sprang unbidden from her subconscious.

Now Robinson has a new nonfiction book, “Reading Genesis,” slated for release in 2024. And she looks forward to revisiting Seattle in June. “At this point in my life, I do tend to think of things as culminating events—and who knows? I think it will feel very good and right to be at the UW again. It was very important to me and beautiful.”

The UW Alumni Book Club is reading “Gilead” by Marilynne Robinson. The reading period is Oct. 13 through Dec, 15, 2023. Learn more and join the club for discussion.