The wild, wild world

of Art Wolfe

The wild, wild world

of Art Wolfe

The wild, wild world of Art Wolfe

The UW and UW Alumni Association present Art Wolfe, '75, with the Alumnus Summa Laude Dignatus, the highest honor bestowed upon a UW graduate.

By Shin Yu Pai | Photos by Art Wolfe | June 2024 issue

To capture one of the most striking series of images from his new photography book, “Wild Lives: The World’s Most Extraordinary Wildlife,” Art Wolfe, ’75, waded into the shallow coastal waters off Mexico to get an intimate view of 12-foot-long crocodiles. Because the crocodiles in this region get handouts from fishermen whose main catch is spiny lobsters, they’ve become accustomed to humans. Working on his knees in 4 feet of murky water, the artist waited with his underwater camera as the massive reptiles swam within a foot of him. Wolfe photographed the animals with their expectant mouths agape, all teeth. “The photos look like you’re about to die,” says Wolfe. When he shows them, “they elicit a gasp from the audience.”

Art Wolfe By Philip Kramer/Art Wolfe Incorporated

For nearly five decades, Wolfe has stunned and thrilled readers with his images. He documents wild species, world cultures, ceremonial practices and distant places to bring them into public view. For his work, Wolfe has been recognized with numerous book and television awards: Nature’s Best Photographer of the Year, the North American Nature Photography Association’s Lifetime Achievement Award and the Photographic Society of America’s Progress Medal for his contribution to the advancement of the art and science of photography. He also has a coveted Alfred Eisenstaedt Magazine Photography Award. This year, the UW will present Wolfe with the Alumna Summa Laude Dignatus Award, the highest honor bestowed upon a graduate for exceptional lifetime achievement. Past artist recipients include composer William Bolcom, ’58, Chuck Close, ’62, Dale Chihuly, ’65, George Tsutakawa, ’37, and Imogen Cunningham, class of 1907.

Though Wolfe, 72, has often been described as a wildlife photographer, he tackles themes that take him beyond the subject of nature. His book “The Human Canvas” placed human figures against elaborate painted backdrops to transform bodies into an abstract landscape. A New Guinean youth with his skin coated in dried, cracked clay stares directly into the camera as he disappears into a parched landscape. Wolfe drew his inspiration from the body-painting traditions of Indigenous peoples, photographing subjects around the world while finding particular resonance with the tribes that he encountered in Ethiopia and Papua New Guinea. Currently, Wolfe is working on a book project called “Active Faith.” This collection of images examines some of the world’s largest religions alongside ritual practices like voodoo and shamanism. And in his newest project, “Photography as Art,” Wolfe draws from decades of taking groups of amateur photographers into unique environments. He often shoots in decaying environments and ruins like World War II concrete bunkers that have been graffitied. Time and place combine to create textured colorful walls that evoke the abstract expressionist paintings of Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Willem de Kooning.

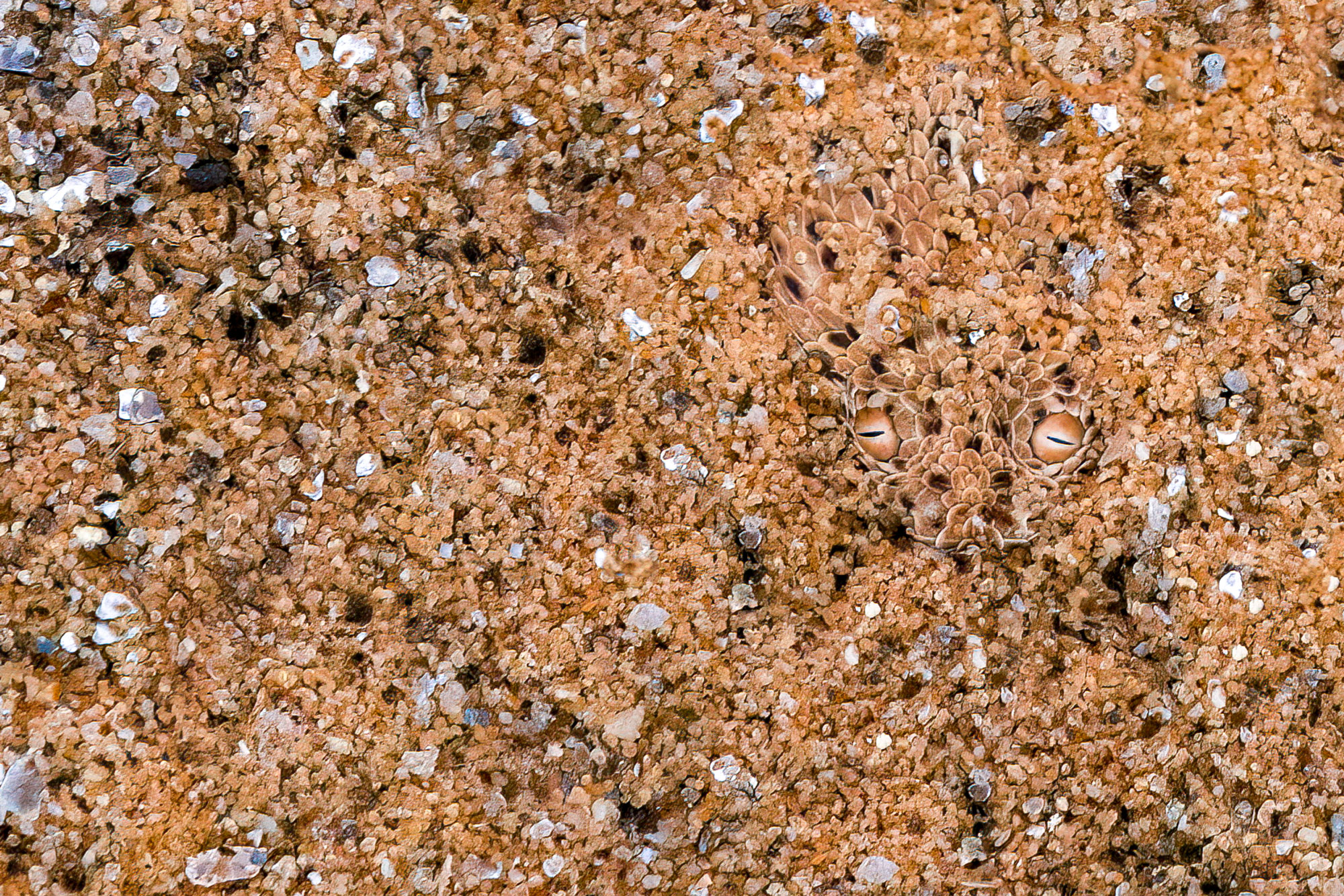

A venomous Peringuey’s adder camouflages itself in the sand in Namib-Naukluft National Park.

Wolfe’s training in painting as an undergrad at the UW shaped his career and sensibilities. As a fine arts major, he worked closely with Hazel Koenig, ’50, and learned about bookmaking, art education and other topics in addition to his painting studies. Under Professor Michael Dailey, Wolfe gained proficiency with watercolor—the medium in which he felt most comfortable. And from Professor Jacob Lawrence, Wolfe learned to experiment and do more things that made him uncomfortable. “It’s why I have such a broad range of genres,” says the artist. “I learned from my instructors at the UW to be broad-based, to not fall into a rut and paint the same things. In my photographic career, I have taken that to heart. I like to say I photograph without prejudice, meaning anything can be a subject for my camera.”

In addition to seven years of painting study, Wolfe spent two years on art education. His experiences in front of the classroom enabled him to work through his anxiety with presenting in front of audiences. After graduating, Wolfe taught for a local school district, where he pushed beyond his fear of public speaking. It equipped him with the confidence to pitch editors with photo-essay ideas and approach larger media outlets with his portfolio. He soon realized that teaching children wasn’t for him and turned his energies to nature photography, a hobby he had started as a teen with a Kodak Brownie Fiesta and had dabbled in while studying art in college. Marrying his artist’s sense of color and perspective with his love of the natural environment, he found his calling. In short order, he had a book project with The Mountaineers and a government contract to photograph wildlife around the country.

Wolfe grew up in a family of artists who encouraged his creativity and a connection to nature. Though his father was a photographer on an aircraft carrier in the South Pacific during World War II, much of Wolfe’s creative inclination was actually nurtured by his mother, a commercial artist. “I was the youngest of three kids. When my mom enrolled in a correspondence course in commercial art,” says Wolfe, “I’d do the lessons alongside her. So from an early age, I was into painting and drawing.

Art Wolfe worked with a Hindu pilgrim in Varanasi, India to capture this image titled “Spiritual Journey.” The shoot took place at dawn along the Ganges River during the Kumbh Mela celebration in 2007.

“When I wasn’t shadowing her, I was out there in the woods [of West Seattle] learning,” he says. “I had a little book on birds, trees and mammals and taught myself how to identify the world surrounding me.”

Wolfe has always been compelled to preserve and protect nature. When he was 12, he fought against a housing development near his home. “I was always playing in a greenbelt we called Forest Court [now Fauntleroy Park] just down the hill from my house. And suddenly, this whole area was being assaulted by road graders and bulldozers,” he says. “A gang of us kids stopped it. We covered the culverts and flooded the roads. I pried gas caps off the machines and poured in dirt by the handfuls. We kept it up until they went away.” In 1972, the wooded ravine was sold to the city and became part of a 28-acre park.

For the past decade, the artist has led annual tours to Alaska, guiding workshops on photographing bears. The brown bears feed on salmon and have been habituated to the fishermen who have worked the waters around Katmai National Park for 60 years. They leave humans alone. “The mothers, with their spring cubs, will bring them nearby and leave them,” says Wolfe. The mother bear will go out fishing up the river just out of view. But she trusts leaving her cubs near humans to prevent them from being killed by male bears, he says. “It’s a great honor to be trusted babysitters for such awe-inspiring animals.”

“As an adult, I have the same awe of nature as I did as a 7-year-old. I love being out in the wild.”

Art Wolfe, ASLD

Professor Samuel Wasser, Wolfe’s former collaborator and endowed chair in conservation biology at the UW, has said, “Art has an extraordinary eye, enormous drive, patience and an incredible ability to see the art in nature.” The pair worked together on the book “Wild Elephants.” “Elephants are enormously social, strongly bonded to kin, extremely intelligent and show great interest in the death of close kin,” Wasser notes. “Those combined features are what make elephants so special but also so vulnerable to the emotional impacts of poaching. Art’s photos beautifully portrayed the wonder of elephants, setting the stage for me to convey the tragedy in what we’re losing when these amazing creatures are poached in large numbers.”

In addition to engaging with conservation efforts, Wolfe dedicates much of his time to teaching through photographic tours, workshops and seminars. He is driven to make better photographers out of the people who come to him.

“If people really want to make a living with their photography, they have to go in with eyes wide open and know that they have to be driven. It was my choice, but I gave up a lot of things, like family and pets.” At the same time, many of the students in Wolfe’s workshops are content simply exploring their creativity. “People who find their passion—what they are happy doing—live longer lives. They have a reason to get out of bed. People who get deeply involved in cooking, writing, dance, have strong relationships—whatever the fulfillment—those are the people that have discovered the secret of life.”

Wolfe is now in his 70s. Next year, he plans on leading a trip to Egypt to see the pyramids. He’s also organizing a walking tour of Paris that will include museum visits as well as an outing to Giverny, where Claude Monet painted his legendary water lilies. “As an adult, I have the same awe of nature as I did as a 7-year-old,” says Wolfe. “I love being out in the wild. When I get too old to travel, I’ll fall back on painting. When I picked up the camera decades ago, it didn’t mean I threw away my easel, inks or brushes forever.”