In 1915 it is a dot on a new campus plan that makes it the center of campus. In 1923 it is a series of working drawings by the head of the architecture department. It later shows up on his family’s Christmas card, including the design for a 260-foot tower that is never built. In 1926 it is one of the “extravagances” that causes the governor to pack the Board of Regents and fire the UW president. In 1927 it opens to great acclaim—the reading room “is pronounced by experts to be the most beautiful on the continent and is ranked among the most beautiful in the world.”

In 1933 it is named after the same president who was fired a few years earlier. In 1935 a south wing opens following the architect’s plan. In 1963 the University discards the original design for a modernist addition by Bindon and Wright. By this point in time, much of the original reading room furniture is “surplussed.” In 1991 it is designated one of the most dangerous buildings on campus during an earthquake.

“It” is Suzzallo Library, the “soul of the University,” according to President Henry Suzzallo and “the dominant feature, not only of the library for all time, but of the University as a whole,” according to its architect, Carl Gould, the first chair of the UW architecture department.

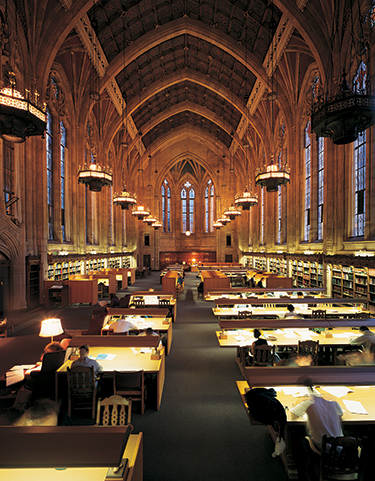

Technically a collection of wings and additions, most alumni think of the western side of Suzzallo when someone mentions the UW’s main library. Built in 1927, it is the campus cathedral—a soaring exterior of 11 monumental stained glass windows, framed by Gothic-inspired statues, arches and buttresses made of terra cotta, cast stone and brick. Inside is the most voluminous library reading room in the nation—65 feet high, 52 feet wide and 250 feet long—a sanctuary for learning.

The famed Reading Room at Suzzallo Library.

Gould’s biographers say it is one of his finest works. One architecture historian calls it the “acme” of Collegiate Gothic at the UW. For the hundreds of thousands of alumni who once studied there, it is a treasured place where they sought inspiration to learn—and, for some, a quiet place to sleep (See “Suzzallo Memories”).

But behind the beauty lurked danger. Because it came together in bits and pieces (besides the 1927 wing, there were additions built in 1935, 1947 and 1963), Suzzallo was a structural disaster in the making. In an earthquake, these wings could move at different speeds, the walls of each section banging against the other.

Add to the structural danger thousands of people walking in and out of the library every day, and you have “high damage potential” and “high life safety danger,” said a 1991 report on the seismic status of campus buildings. Engineers ranked it and Hec Edmundson Pavilion as the most dangerous campus buildings in an earthquake.

Though it had to try twice, the UW convinced legislators in 1999 to fund the costly work-the total comes to $47,259,167. About 95 percent of the budget was spent on seismic and life safety work, and only 5 percent on remodeling, explains Assistant Librarian Paula Walker, who oversaw the library’s side of the project.

As students, faculty, staff and alumni walk through Suzzallo when it reopens this month, they might wonder where all the money went. But that reaction is exactly what librarians, architects and engineers want. Their goal was to hide as much of the seismic work as possible, returning rooms in the 1927 and 1935 wings to their original state.

One of the gargoyles looking over Red Square from Suzzallo Library.

Looking at the ornate ceiling in the reading room, there is no sign that behind the plaster lie tons of steel truss work, linking the 1927 wing to the other parts of the building. Workers poured three stories of concrete shear walls in the north and south ends of the wing and then added steel bracing up to the ceiling, but the work is hidden in utility closets and mechanical space.

For a sign that the building is much stronger, visitors have to leave the reading room. Outside, almost floating above the entryway, is what engineers call a “bat wing,” a web of steel truss work that arches over the ceiling, connecting the 1927 wing to the rest of the building. Other signs of strengthening include exposed X-beams coming through the floors of the area outside of the reading room and in parts of the 1963 addition.

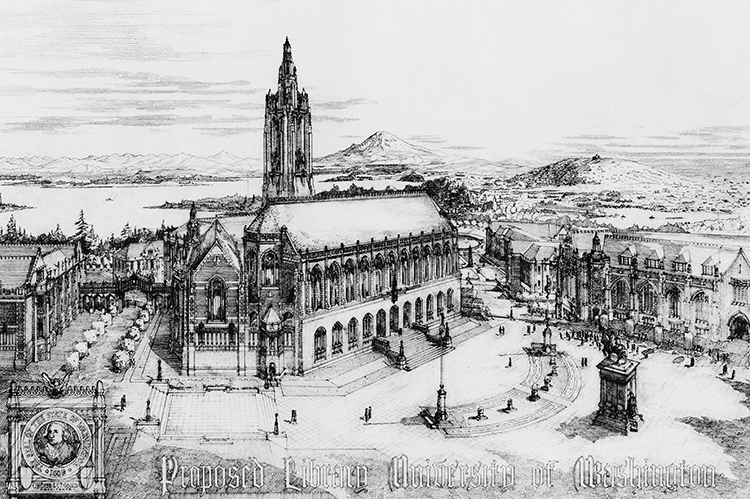

Much of the seismic upgrade depends upon something that was never built—a 260-foot bell tower that was supposed to rise above the main library. As tall as the Smith Tower, Seattle’s tallest building at the time, the spire was going to be the focal point for the entire campus. When the original wing was built in 1927, the work included pouring footings and building columns to serve as the base for the future tower.

“When we investigated the bones of the building, we looked at the designs for the spire,” says Jay Taylor, ‘80, the main structural engineer on the project and a principal at Skilling Ward Magnusson Barkshire. “Part of our strategy is to use as much of the strength of the existing building as we can.”

What Taylor found was exceedingly strong footings and columns designed to support the spire in high winds. With added bracing, they were exactly what the engineers needed to anchor different wings of the building. The new truss work connects to these older columns so that the three oldest wings now move as one in a quake.

A 260-foot spire was part of the original design for Suzzallo Library.

While the old footings finally have a functional use, Architecture Professor Emeritus Norman Johnston, ‘42, laments that the 260-foot tower was never built. “It would have more dramatically enhanced Gould’s concept,” says Johnston, the author of The Fountain and the Mountain and The Campus Guide: University of Washington. “It would have dominated the University’s skyline.”

At that time, any university aspiring to greatness had a bell tower; look at Stanford and Berkeley,” adds T. William Booth, a retired architect who co-wrote the biography Carl Gould: A Life in Architecture with William Wilson. “Gould’s tower would have been a knockout.”

Not that either expert thinks the building is a failure. “It is as close as we come to a cathedral,” Johnston notes. Wilson says it is Gould’s finest “historicist” structure and ranks it among his best works.

The idea for a massive central library goes back to the 1915 campus plan, drawn up by Gould and his partner, Charles Bebb. Modifying earlier plans, they envisioned a central plaza that would link a liberal arts quadrangle to the east with a science quadrangle to the south. At one end of that plaza they marked the spot for the central library.

Johnston calls it the “knuckle” of the campus. “Its placement links together the arts and humanities with the sciences,” he says. “It symbolizes that this is a university dedicated to knowledge and learning.”

When the regents approved the original plan, they also approved the UW’s official architectural style: Collegiate Gothic. President Henry Suzzallo arrived soon afterward and embraced the plan. The UW’s setting “disturbed me greatly when I first came,” he later wrote. “The campus was naturally beautiful, but the buildings were ugly.”

Suzzallo Library during its construction.

Beauty was an important part of Suzzallo’s vision for the UW, a place where students are made “moral” and “intellectual.” “Intellectuality and morality are doubled in their efficiency when the grace and appreciation of beauty are added,” he declared.

He and Gould toured libraries at Stanford and Cal-Berkeley to prepare for the UW library. Gould later visited public libraries in San Francisco, Detroit, New York and Boston. He was particularly inspired by the design of the Boston Public Library, Booth says, which also has an upper level with high windows that send daylight into a grand reading room. Another influence was the Liverpool Cathedral, then under construction in England, a neo-Gothic edifice with a commanding tower.

In Gould’s final concept, the library was supposed to be built in stages: three wings that formed a triangle. A fourth wing to hold the library’s stacks jutted out of the triangle at one of its points. The tower rose from the center of the triangle.

But the rest of Gould’s concept was lost in the 1963 addition by the architectural firm of Bindon and Wright. “The addition will have a modern architectural treatment to harmonize with the present Gothic structure,” the Washington Alumnus reported in 1961. But the result-a boxy office building made of glass and concrete—was anything but harmonious. Both Booth and Johnston say it is a mistake-and almost everyone else on campus agrees.

“By that time, the size of the library collection had outgrown Gould’s original plan,” says UW Project Manager Olivia Yang. The push was to build a big box with windows that couldn’t open. “I think it was the first air-conditioned building to be built on upper campus,” she reports.

Some of that addition was covered up by the Allen Library when it was built in 1990. Officials considered covering up the rest of the 1963 wing during the current renovation, but the cost was a budget-buster. For now, librarians and the rest of the campus community are resigned to live with it.

One of the grand doorways to Suzzallo Library.

Even though Gould’s concept was never fully realized, his work has touched the lives of thousands of students, faculty and visitors, just as he and Suzzallo had intended. That impact is now preserved for future generations. The amount of time, money and care that has gone into its restoration should be a source of pride for today’s librarians, administrators, lawmakers and state citizens, adds Johnston. “They came to the rescue,” he says.

“You could never build another Suzzallo,” adds structural engineer Taylor. “It is just so unique. You could never replace it for $47 million.”

The 1927 wing has survived three earthquakes, Vietnam War riots, presidential sackings and even the blight of the 1963 addition—and it still works its magic. As W. E. Henry, the UW’s head librarian, said of the reading room when it opened its doors for the first time: “Any generation of students who shall be fortunate enough to read through four years in that room will carry with them from the University something vastly more significant and enriching than any facts they have ever been able to put upon examination papers.”

The public is invited to two special events to commemorate the reopening of Suzzallo Library. A ribbon cutting ceremony featuring the Husky Marching Band will be held at 11:30 a.m. Monday, Sept. 30, the first day of classes, on the steps of Suzzallo. Beginning at 2:30 p.m. on Thursday, Nov. 14, there will be a special dedication ceremony with music and guest speakers held in the Suzzallo Reading Room. For more details, visit the UW Libraries Web site.

Shaking up Suzzallo

The seismic upgrade preserved the graceful beauty of Suzzallo’s stairways. Photo by Mary Levin.

On Feb. 28, 2001 the Nisqually earthquake rattled western Washington. Brick buildings collapsed in Pioneer Square, roads buckled across the region and a column cracked in the state Capitol Building.

But Suzzallo Library stood tall. The state had funded a $47 million seismic upgrade in 1999 and work had started the summer before the quake. With 60 percent of the interior seismic work already completed on that date, there is some indication that the damage could have been worse. Jay Taylor, ‘80, the project’s structural engineer, said there were diagonal cracks in the masonry walls of the Suzzallo Reading Room, but they stopped at the point where new bracing was already in place.

As it was, the damage was mostly cosmetic. Four of the terra cotta pinnacles that punctuate the roofline fell, smashing on the library’s front steps and the roof of a construction trailer.

The University went back to the firm that originally cast the pinnacles in the 1920s—Gladding McBean in California. Taking molds from undamaged pinnacles, they made exact duplicates.

Meanwhile, construction workers continued to strengthen the filigree that decorates the exterior of the west wing. “There non-structural elements can be falling hazards and even kill somebody in a quake,” says Taylor.

The balustrade that accents the roof now has fiberglass fabric hidden behind its terra cotta outline to hold it in place. The pinnacles and towers have steel pins anchoring them to the main structure.

But even with the new bracing, Suzzallo is vulnerable to a 9-point superquake that scientists predict could one day rock the Puget Sound area. “The building will be damaged in a quake like that,” Taylor says. “What we try to do is prevent loss of life. We strengthen it so that it doesn’t collapse and people can safely exit the building. People will have time to get out.” —Tom Griffin

Suzzallo facts, figures, oddities

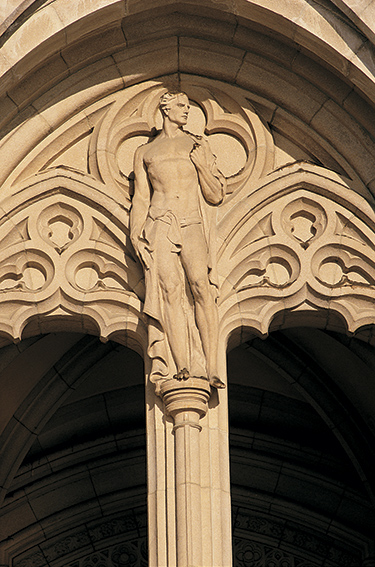

“Thought” statue above the main entrance to Suzzallo Library.

Across the west façade of Suzzallo Library are statues of 18 “great thinkers”—a list of “who’s hot” in 1923 academic circles. UW President Henry Suzzallo asked the faculty that year for nominations and got back 246 names. A committee made up of Suzzallo, Regent Winlock Miller and Dean David Thomson made the final selections and the UW hired Tacoma sculptor Allan Clark to make the figures out of terra cotta. No one is quite sure why they were placed in the order they are, but, from left to right, the figures represent Moses, Louis Pasteur, Isaac Newton, Leonardo da Vinci, Benjamin Franklin, Justinian, Herodotus, Adam Smith, Homer, Johannes Gutenberg, Ludwig von Beethoven, Charles Darwin and Hugo Grotius.

These are not the only works by Allan Clark that grace the building. Above the main portals are three heroic figures of cast stone representing “Mastery,” “Inspiration” and “Thought.” Horace C. Henry financed the three pieces just a year before he donated the funds to build the Henry Art Gallery. According to library records, the UW buildings and grounds superintendent, Charles C. May, posed for the athletic “Mastery” statue. Clark asked a Tacoma woman, Jean Lambert, to pose as “Inspiration,” but there is no record of the model for the ancient “Thought” figure.

Stained glass in the windows at Suzzallo Library.

The seals of many great universities-including even a few rivals of the Huskies on the football field-adorn the western façade of Suzzallo Library. Included are seals for Bologna, California, Harvard, Heidelberg, Louvain, Michigan, Oxford, Paris, Salamanca, Stanford, Toronto, Upsala, Virginia and Yale.

Inside the Suzzallo Reading Room are still more symbols of learning. In the stained glass windows are 28 watermarks from European papermakers of the late Middle ages and early Renaissance. An ornamental carved oak frieze rests above the reading room bookshelves. The carvings celebrate native flowers and shrubs such as salal, Douglas fir, scrub oak, dogwood, grape, trillium, salmon berry and rhododendron.

After it opened, the building did reveal some idiosyncrasies. The reading room was so dark that eventually librarians cut off part of the chandeliers so that they would give off more light. The original doors had beautiful ironwork, but they were deemed “too heavy” for coeds to open. The hand-crafted ironwork became scrap for the campus metal shop.