For years, Ted McGregor dreamed about moving home and starting a newspaper. A former intern at the Seattle Weekly and part-timer at the Seattle bureau of The New York Times, he had developed a knack for journalism and a love of writing. And he thought his hometown—with its quirks, blue-collar base, gritty history and abundant beauty—had a great many stories to tell.

Still, it might be harder than he imagined. The city of about 200,000 with a metropolitan area of half a million had a reputation for being slow to embrace the new. While its counterparts across the state boomed under the influence of technology, scientific research and innovation, little seemed to change in the river city.

Elements of its early 1900s heyday—mansions built by mining and timber fortunes as well as sprawling Olmsted-designed parks—ornament the city. The surrounding natural resources of ore-rich mountains, fish-filled rivers and abundant farmlands that lured the first settlers remain its biggest assets.

The city’s landmarks include a massive waterfall that was once the site of a village of the Spokane tribe. Now it is encased in a 100-acre park that dates to the 1974 World’s Fair. The falls are neighbor to a garbage-eating goat sculpture made by a blowtorch-wielding nun. It is a community of ranchers and steelworkers, artists and educators. Hometown of crooner Bing Crosby, designer George Nakashima, ’29, and folk star Chad Mitchell, Spokane is at once weird and wonderful. As Ted once wrote of the place: “The past and present collide for me, with a million stories stretching in all directions.”

The city lured Ted and his brother, Jer, fourth-generation Spokanites, home in 1993 to start a weekly newspaper. Their timing was good. The city had a struggling subculture of artists and writers, community leaders primed to save old buildings and build new ones, and young people eager to move there for a quality of life that included affordable homes and abundant outdoor activities.

They have since built the Inlander into a community staple with a circulation of 50,000. They also produce a slew of city guides, and host and support a number of annual events that celebrate Spokane-specific food, music and sports.

In 2013, the McGregors’ push for permanence culminated in a headquarters in one of the city’s newest urban developments. It’s a long way from their first offices, the dated bedrooms of a bungalow northwest of downtown. Their new three-story glass-and-steel structure perches on a cliff about 150 feet above the Spokane River.

As Ted looks out his office window on a recent summer afternoon, he explains that a decade ago the whole area was mostly rail yard and contaminated land. Tonight, on the manicured street just outside, farmers and vendors set up for a lively night market. “You could say that for the last 15 years, parallel with our story is the story of Spokane,” he says.

Jeremy and Ted McGregor, facing camera, meet with fellow Inlander employees.

Deep roots

For more than a century, McGregors and Peirones have made their homes in the Inland Northwest. Domenico Peirone, Ted and Jer’s maternal great-grandfather, literally carved his living from the basalt landscape. A stonemason from Italy, his handiwork can be seen in the city’s Arts and Crafts-era houses from quaint cottages to grand mansions.

In 1945, Domenico’s son Joe, Ted and Jer’s maternal grandfather, turned his produce delivery effort into a full-fledged business: Peirone’s Produce. One helpful neighbor and regular customer was Archie McGregor, the proprietor of Sander’s grocery, and Ted and Jer’s other grandfather.

Both boys grew up playing outdoors, with family all around, and a wide circle of friends. “They are both the sort of people who make and keep friends,” says their mother Jeanne.

They attended Gonzaga Prep, a Jesuit high school that offered a rich diet of literature, math, history, college preparatory courses, service and social justice. But like many college-bound kids from Spokane, both wanted to go away for school. Ted started his decade-long journey at the University of Washington, where he studied writing and history.

As a sophomore, he already knew he wanted to be a writer. “Becoming a journalist came later as a more practical way to find a career path,” he says. He loved Jon Bridgman’s year-long world history series and savored Willis Konick’s Russian literature courses. “Great writers inspired me in the classroom,” he says, “while the great city of Seattle inspired me outside it.”

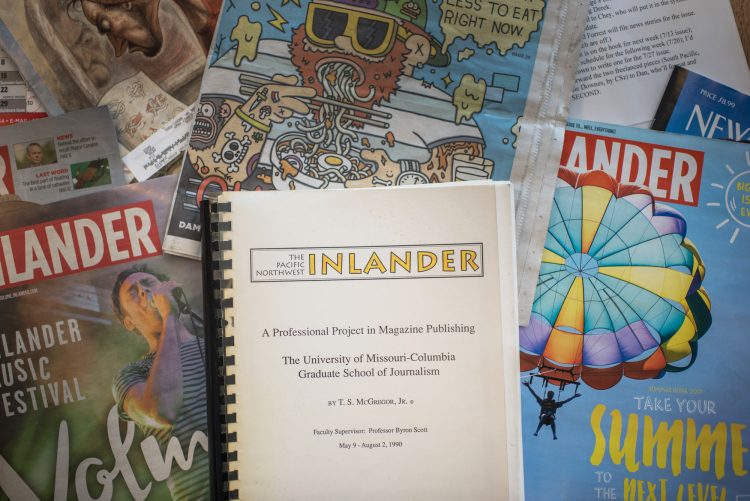

An Inlander cover story: “Cheap Eats: 56 things for $10 or less to eat right now.”

After college, Ted landed a part-time job at the Seattle bureau of The New York Times. At that time, the offices were upstairs in the Seattle P-I building and (pre-Pulitzer, post-Spokane) Timothy Egan, ’81, was settling in as a reporter there. In him, Ted found a kindred spirit and a mentor. “I can still see him sitting back there saying, ‘So you went to [Gonzaga] Prep, huh? Me, too,’” he says.

Ted also interned at the Seattle Weekly. “My little desk was right outside [founder] David Brewster’s office,” he says. He relished watching a team of great writers and advertising executives in action. “That was an inspiring place.” But his hometown was always on his mind. “I felt like this was where I’d end up,” he says of Spokane. “And I realized the only way we’d move back was if we could start a business.”

Portland has the Willamette Week, Chicago has its Reader and Seattle has both the Weekly and the Stranger. Ted believed that any city with a healthy arts scene could use an alternative paper. On the advice of Wallace Turner, The New York Times’ Seattle bureau chief, Ted enrolled in graduate school at the University of Missouri. There, while developing his plan for Spokane into a master’s thesis, Ted met his wife, Anne Flavell. He followed her to Boston, where she attended graduate school and he honed his expertise at a regional newsweekly.

Jer, who trailed five years behind Ted, had followed him to the UW. He joined Ted’s fraternity, Psi Upsilon, and even took courses from his favorite professors. He credits his English major for helping him organize complex thoughts and convey them in a compelling way. “In business, being able to articulate who you are, what you stand for and how your business can help other businesses succeed is often the difference between success and failure,” says Jer. “The writing skills I learned at the UW are in heavy use every day.”

Ted McGregor completed his degree at the University of Missouri-Columbia Graduate School of Journalism with a report about the newspaper he would later start.

After graduation, Jer planned to stay in Seattle and shoot for law school. But then the phone rang. Ted was wondering if Jer might come home and help. “I guess I knew I couldn’t do it all myself,” says Ted. And he couldn’t think of a better partner than his brother.

One of the next calls Ted made was to Boston, with an invitation to a former coworker, Andrew Strickman, to become the first arts editor. Strickman, who had interned at the Village Voice, was intrigued. He flew out to meet Jer and their mother Jeanne, who was helping fund the launch of the publication. “I sort of fell in love with Spokane immediately,” says Strickman. “It’s a beautiful, bucolic place. Definitely the kind of place that a young guy who is looking to make his mark on the world could benefit from.”

Today Strickman lives in San Francisco and works as head of brand marketing and chief creative at realtor.com. He cites his years with the Inlander as particularly formative. “It was a very, very exciting time on so many levels,” he says. “I remember walking into the chamber of commerce in Spokane one afternoon to see about getting a membership. The woman at the desk looked at me and asked, ‘Why would we need another newspaper in Spokane?’ That was just the kind of firebrand experience that led us to have even more resolve.”

That first decade was rough. Potential advertisers turned them away, saying they wanted to wait a year or so to see if the paper survived. “We were always catching up and catching our breath and learning how to be in business,” says Jer. Fortunately, they had their grandfathers’ tenacity and the support of family members; their mother even helped by hitting the sidewalks and selling ads store by store.

“Ted is an original thinker, a great voice for Spokane and beyond. His paper has meant a lot for people looking for fresh ideas east of the Cascades.”

AUTHOR AND COLUMNIST Timothy Egan, '81

While Ted led the editorial side of the paper, it was up to Jer to sort out the business. They all worked late into the night to meet the deadline, building the issue page-by-page. As soon as the edition was printed, Jer, in his beat-up Forerunner, and a team of paper carriers were out stuffing the issue into the racks of grocery stores and coffee shops around town.

Jonathan Martin, ’95, now an editorial writer at the Seattle Times, was a housemate with Jer at the UW. He remembers the Spokane native always talking about how great it was to grow up there. “He always felt like Spokane was just a hidden gem waiting to be polished,” says Martin.

Jeremy McGregor at the entrance of The Inlander.

When Martin moved to Spokane in the mid-1990s for a job at the mainstream newspaper, the Spokesman-Review, he shared a house with Jer and another reporter. He also made friends with Tamara Lehman, a local TV producer and reporter who would become Jer’s wife. “We were all a little disturbed with how much Jer worked,” says Martin. “He was literally working 80 hours a week. He would drive around town with copies of the Inlander in the back of his truck.”

In addition to selling ads, Jer taught himself to design them so he could help out the small-scale advertisers. He is the force behind the paper’s broader projects and sponsorships like a regional guide called the Annual Manual and yearly events like the Inlander Music Festival, the Inlander Winter Party and the Inlander Restaurant Week. The publication’s team also sponsors the Lilac Bloomsday 12K race and Hoopfest, two nationally-recognized sporting events that draw tens of thousands of people to Spokane each year.

“In embracing the food and entertainment culture, they’ve just really enhanced it,” says Don Kardong, ’74, founder and current director of the Bloomsday Run. “There’s a lot going on here now and I think they are responsible for a lot of it.”

Branching out

One side of the new Inlander building looks out over the Spokane River, where an osprey floats on air currents just in front of Ted’s window. This new home was an ambitious project, but also a sign that the newspaper is now very much part of the Spokane landscape. “It was a gut check for Jer and me to do this,” says Ted of opening a building in the middle of the redevelopment project. “But we were glad to be able to be part of this. We want to feel new. This is about looking forward.”

The 78-acre Kendall Yards project isn’t the only significant difference in the city since the Inlander was born. The newsweekly heralded the birth of a craft brewing movement, celebrated when local writers Sherman Alexie and Jess Walters achieved national acclaim and cheered the city’s efforts to stay viable and livable.

“When we started, Spokane was ready to change, and now it’s changing,” says Ted, who has long advocated in his column for downtown revitalization. Now that the publication is thriving, he has found another way to give back to the city. As the volunteer leader on a $65 million city project to update Riverfront Park in the heart of downtown, Ted is helping shape the future for the 100-acre site.

Jeremy and Ted McGregor at the Inlander office building that overlooks the Spokane River.

“I was so impressed by the way Ted took what he learned in graduate school and then applied it to Spokane, and made a great success of it,” says Egan, his old friend from The New York Times. “Ted is an original thinker, a great voice for Spokane and beyond. His paper has meant a lot for people looking for fresh ideas east of the Cascades.”

And for that, they’ve been recognized. In 2016, media industry journal Editor & Publisher named the newsweekly one of “10 newspapers that do it right.” The review lauded their efforts for launching community events, venturing into digital content, taking risks and having a start-up mentality.

“It’s not just a newspaper, it’s a community-minded organization,” says Jer. Feeding and fostering the city’s creative culture, supporting local business, celebrating the local economy—all are part of their ethos.

“Reading the Inlander will help you understand the community better,” says Jer, “and perhaps enjoy it a little more, too.”