Seeing myself in a

125-year-old photograph

Seeing myself in a

125-year-old photograph

Seeing myself

in a

125-year-old photograph

I'm a computer science major, but it was an art history class that shaped how I understand our complex and broken world, and also allowed me to better know myself as an Asian American.

By Elizabeth Xiong | July 6, 2021

It was 5:50 AM, my last day of virtual freshman orientation. I woke up early to register in hopes of snagging one of the five remaining seats in Art History 220. The course sounded interesting to me, but I was mostly looking to fill a general education requirement, nothing special. As autumn quarter flew by, Professor Juliet Sperling led the class through a sweeping tour of American art, from deceivingly beautiful colonial portraits to bewildering pieces of contemporary art. Little did I know how much it would profoundly shape me.

However, I felt like something was missing. Even though we discussed the Japanese woodblock prints that inspired work by painter James Whistler, I now see how the course could have featured more works of—and by—Asian Americans. But for an ashamedly long time, I hardly noticed.

I’m a computer science major, but when registration rolled around for next quarter, I signed up for another art history course with Professor Sperling, this one about photography. Each week was dedicated to “re-reading” a well-known, controversial or forgotten American photograph. For me, these scholarly re-readings transformed art into something more than just objects hung on museum walls. As the quarter progressed, I saw the personal connection that many scholars had to the photographs they wrote about, and this in turn led me to realize what I had been missing when studying American art.

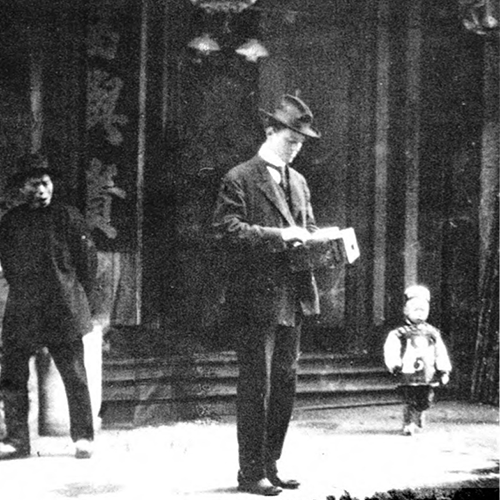

As I scrolled through a curated list of potential images to re-read for my own research paper for the class, one forced me to pause: “An Unsuspecting Victim.” The black-and-white photograph by Arnold Genthe was unassuming at first: two men stood by a young boy on the street. A strange title.

Then I looked again, and all of a sudden the man on the left reminded me of my grandpa, and the young boy looking directly at me was reminiscent of a photograph of my dad when he was growing up in China. Then it struck me. I knew nothing about Asian Americans in art or photographs despite having surveyed American art. I knew little about the early immigrants who looked like me, who shared a similar culture and language with me. Everything I thought I knew came from a couple bullet points on a PowerPoint slide from high school.

“An unsuspecting victim” by Arnold Genthe

Taken in 1896 San Francisco’s Chinatown, that pictured street is packed with a long forgotten history. It was the peak of the Chinese Exclusion Act, when law after law directly targeting the livelihoods of California’s Chinese immigrants was being passed. Chinatown was essentially a city within a city, segregated from the rest of San Francisco, where thousands Chinese immigrants could only find work, food, and lodging within those ten street blocks.

You might be tempted to think this 125-year-old photograph has little to do with America today, with Seattle, with the UW, with you. I urge you to look again and follow along. You might be surprised, just as I was.

“The man on the left reminded me of my grandpa, and the young boy looking directly at me was reminiscent of a photograph of my dad when he was growing up in China. Then it struck me. I knew nothing about Asian Americans in art. I knew little about the early immigrants who looked like me, who shared a similar culture and language with me.”

* * *

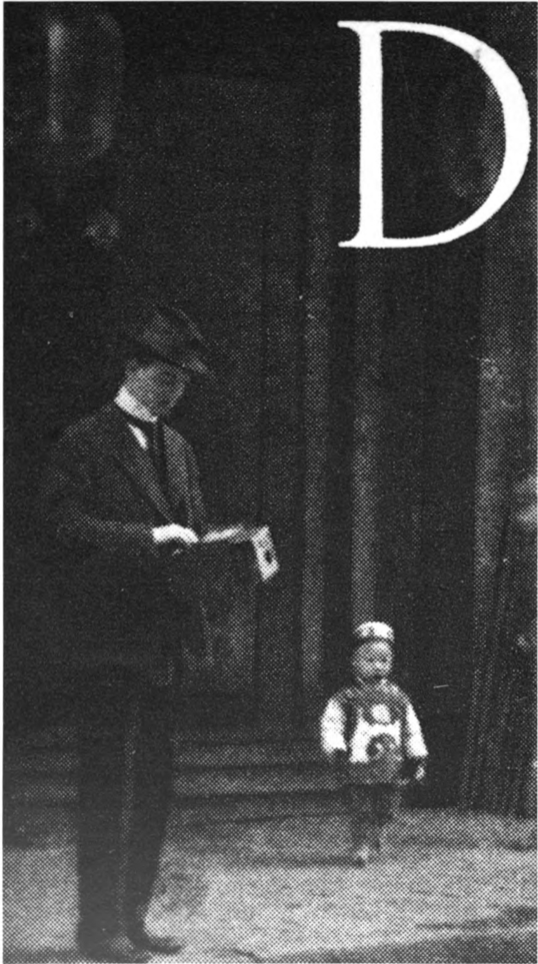

Whether it’s moving the edges of a photograph or Photoshopping the areas we aren’t satisfied with, most people don’t think twice about the everyday digital crop. However, during Genthe’s time there wasn’t an undo button, and cropping was a far more deliberate and permanent process. Nineteenth-century “Photoshop” required physically retouching the surface with chemicals and tools. Genthe himself fervently utilized these techniques in his photography, but the more I researched him, the more I discovered that his intentions were not trivial nor innocent.

With Genthe’s track record of manipulating images, it’s no surprise that a quick internet search pulls up two other versions of the first image we looked at. “Self-portrait with Camera in Chinatown,” not intended to be seen by the public, is the original; and “Postscript” is the final version Genthe published. Prominent art historians Anthony Lee and John Tchen have interpreted this series of extreme cropping, from nine figures to two, as Genthe’s attempt to further isolate Chinatown’s inhabitants for his own gain.

“Postscript” by Arnold Genthe

So, what should we look at? Notice how the Chinese children in Western clothing playing on the right side in the original are suddenly unseen in subsequent versions. Additionally, Genthe’s white companion has been erased, accentuating his singular white presence in comparison with his surroundings. Therefore, as Genthe crops out whatever elements aren’t exotic enough for him, it reveals his attempts to paint the Chinese as not only different from him, but as racially and culturally inferior in contrast with the rest of American society. This fulfilled his audience’s expectations, and it contributed to rampant anti-Chinese legislation and sentiment in the 19th century.

An excerpt from the book Longtime Californ’: A Documentary Study of an American Chinatown then brought me face to face with that isolation. A Chinese immigrant living in San Francisco’s Chinatown during the early 20th century, Wei Bat Liu recalls how “if you ever passed [the boundaries] and went out there, the white kids would throw stones at you.” He continues: “One time I remember going out and one boy started running after me, then a whole gang of others rushed out, too.”

I had also discovered Arnold Genthe was also a new immigrant to the United States, but from Germany. Completely contrasted to the Chinese immigrant experience, Genthe casually described his freedom to wander the streets of Chinatown at his leisure in his autobiography As I Remember. Having walked through the streets of San Francisco’s Chinatown a few summers ago, I realized my walk was far too similar to Genthe’s. I came out of that trip as nothing more than a tourist, having learned nothing about the locals who shared the same Chinese roots as me, or the decades of mistreatment that the community has endured. Shocked by my hypocrisy and ignorance, I was determined to use this as an opportunity to put Genthe’s photographic borders in dialogue with the urban, cultural and socioeconomic borders that surround and constrain Chinatown in order to reveal the often forgotten histories around those edges.

The weight of knowing that four streets close off the ten blocks of Chinatown from the rest of American society suddenly causes “An Unsuspecting Victim” to feel increasingly suffocating. The edge of the sidewalk is barely visible, and the older Chinese man and the young boy are separated from that ledge by a sea of overexposed white. This distance gives off the impression that even if they made their way to the edge—to freedom—there is no solid ground to catch them. So they remain in the background, blocked by the border Genthe imposes, and echoing the lack of movement in and out of Chinatown.

Author Elizabeth Xiong

“When others first look at me, I am not considered an American until they hear my English. Even then I have had strangers ask me, full of surprise, how my English became so fluent. I have gone through what my Asian Americans peers now consider a rite of passage: having your lunch ridiculed by classmates, then coming home from elementary school heartbroken and angry, begging for sandwiches instead.”

Photographer Arnold Genthe immigrated to the United States from Germany.

As we’ve seen, borders of urban space were not malleable for Genthe’s subjects in ways the borders of the photograph were malleable for him as the photographer. Re-reading Genthe’s photography gives us a small glimpse into the lives of those he photographed, but it isn’t the full picture. A good first step to better understand the Chinese immigrant experience is through those who lived it: their oral stories, writings and importantly their art. Many of Genthe’s subjects remain unidentified, but stories like Mr. Liu’s give a voice to the voiceless and powerfully reclaim Asian American history. It’s our duty to unearth and prioritize them.

Although borders for Chinese Americans may look different now, interrogating them cannot be limited to the past. In a book documenting anti-Chinese prejudice in America, sociologist Dr. Ai-li Chin writes that “for most Chinese [now] the problem is not so much physical barriers… as it is a question of identity.”

My parents left Beijing for Oklahoma just thirty-two years after the Chinese Exclusion Act was fully repealed. With two suitcases and $200, they came in search of a better life. While there was no law prohibiting them from attending graduate school or coming to America, they still encountered borders that were reminiscent of the past. At one point it was nearly impossible to obtain a passport, let alone a visa and scholarship money. On top of all that, the unavoidable language and cultural barriers immediately labeled them as foreigners.

The reality of questioning identity as a major barrier for today’s Chinese Americans is also especially significant in my own life. Dr. Ai-li Chin asks the young American-born generation, “Who are you as a Chinese in the United States?” Born and raised in Washington state I now ask myself: Who am I as a Chinese woman born in the United States?

When others first look at me, I am not considered an American until they hear my English. Even then I have had strangers ask me, full of surprise, how my English became so fluent. I have gone through what my Asian Americans peers now consider a rite of passage: having your lunch ridiculed by classmates, then coming home from elementary school heartbroken and angry, begging for sandwiches instead.

On the contrary, when others first look at me in China, I am immediately considered one of them, until they hear me speak Mandarin and then consider me as American. I have had strangers scoff when I struggled to read characters on a billboard perfectly, and tell me how I’m definitely American and not actually Chinese.

So perhaps my answer to “Who are you as a Chinese in the United States?” is that I am caught in a balancing act between these two cultural boundaries. A space of in-betweenness where I am not quite American enough, but also not Chinese enough. Despite the challenges and unanswered questions that come with that, I am immensely proud to be Chinese-American. The sacrifices my parents made to be first generation immigrants, coupled with my experiences growing up in America, are the reasons why I’m here at the UW, here sharing my research, insight and writing with you.

Let’s take one last close look at “An Unsuspecting Victim.” Discreetly camouflaged, you’ll see the remnants of Genthe’s white companion as a shadow on the stairs. Perhaps in the same way, similar to that shadow, the borders and mistreatment of America’s 19th century Chinatowns still resonate on the streets today. These photographs are of the past, but that does not mean that history is to be left there, forgotten or excused.

For many, injustices facing Asian Americans today may be just like that shadow: barely seen, fleeting, not tangible. However, the unsettling similarities between violence at the edges of San Francisco’s Chinatown during Genthe’s time and that of the Bay Area this past year obliterate those misconceptions, and our city is not exempt. A 10-minute drive from the UW campus is Seattle’s very own Chinatown-International District, a community that, similar to San Francisco’s Chinatown, also suffered under extreme social, political and economic discrimination in the late 19th century. Yet, we also cannot limit this conversation to the 19th century. Racism towards Asian Americans, especially the community’s most vulnerable, is not just a shadow of the past. It is still here now.

For the past year as the world struggled to cope with COVID-19, headline after headline reported surges in verbal and physical assault against Asian Americans. San Francisco. New York. Atlanta. But less reported is Seattle, where an Asian woman was violently attacked on the streets of Chinatown-International District, saying in a press conference, “since that attack… I haven’t gone back.” This was not an isolated incident, as hate crimes targeting Seattle’s Asian community have increased. We are afraid to walk our own streets—which is an all too familiar statement.

However, few people talked about it, and everything felt somewhat distant from my life in southwest Washington. As each headline became harder and harder to read, I tried pushing down the fear, as if ignoring them would help relieve my feelings of helplessness. It didn’t.

Then, a week or so after the March 16th Atlanta shooting, family photos of the six Asian women who lost their lives that day were released. Glimpses into their immigrant story, and their lives as mothers, were released by mourning family members. I was heartbroken. In those smiling photographs, and in each word detailing their life of perseverance, strength and sacrifice—I saw my mother. I saw my aunt, the women at my small Chinese church, and the friendly faces at my local Asian grocery store, all reflected in those shared stories. Suddenly it wasn’t just a breaking news story that had nothing to do with me, or photographs I could scroll past and forget about.

I knew I had to do something, and with Professor Sperling’s guidance and encouragement, art history has given me this chance to share my findings and my story. The process has not only shaped how I understand our complex and changing, yet broken world, but also provided opportunities where I can better know myself, and especially this past quarter, who I am as an Asian American.

Coming to the UW as a computer science major with little prior programming experience, I hoped to find my place in computer science integrated with something that I was passionate about. Now I can confidently say that I may have found a path to that place. Although computer science is often focused on getting the right answer, art history has challenged me creatively, and pushed me far outside my comfort zone. It has taught me that it’s OK to not have the full answer yet, and oftentimes it is in those very moments where I’ve learned the most.

I’ve seen how art comments and touches on every aspect of life—from what’s comfortable, to confronting the uncomfortable, and always going beyond what I first assume. I see computer science playing a vital role in helping more people experience moments like those for themselves. Technology connects people with new ideas in an increasingly accessible way, and art history generates those new ideas that help us grow to better understand ourselves, our communities and our shared histories. The space between these two fields excites me, and it’s something I will be pursuing passionately in my time at the University of Washington.