At the periphery At the periphery At the periphery

Artist Mary Ann Peters creates works of difficult beauty in her explorations of displacement and migration.

By Shin Yu Pai | Photos courtesy of Mary Ann Peters | June 20, 2024

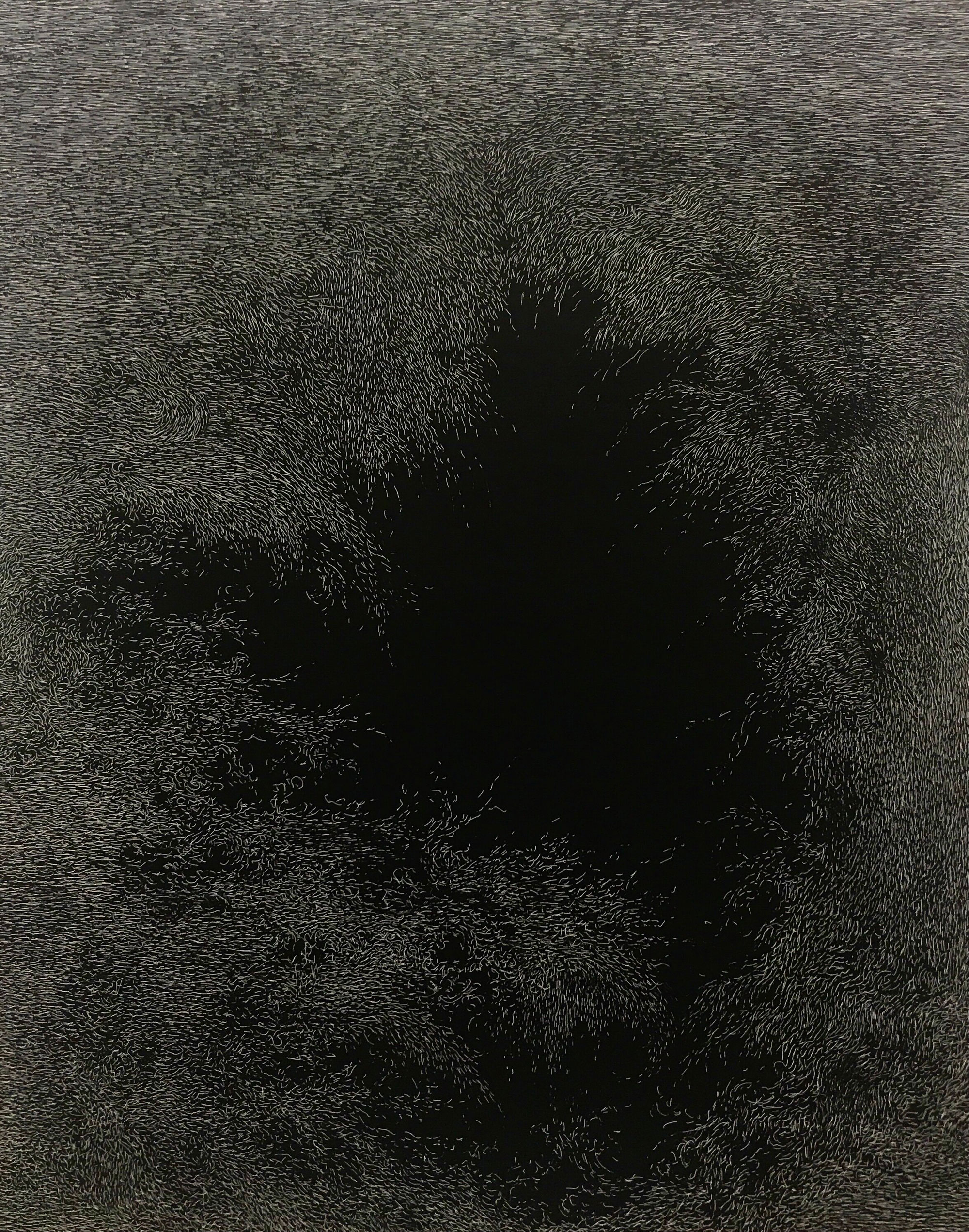

Artist Mary Ann Peters, ’77, calls attention to the things people are trying not to see. She brings pathos and kinesthetic empathy to the works in her new show “the edge becomes the center” at The Frye Art Museum, where admission is free. A series of white ink drawings on black clayboard called “this trembling turf” evokes burial sites uncovered by forensic anthropology, while “impossible monument (gilded)”, a new installation piece, uses the symbolism of keys to suggest displacement from homeland and the inability to return home. Translucent glycerin oval blocks emerge from the wall, weeping as they collect moisture from the air.

Peters’ drawings reflect how the land often holds histories in uneasy ways. The artist came across information on an unverified mass gravesite buried beneath a golf course in Beirut. Because the site is disputed, Peters didn’t feel ethically justified in speaking to that specific history. So she researched forensic anthropology and technologies that allow people to find things that are buried. She discovered a pulsing device that works like a sonagram. “All of the drawings, except for one, have a pulse embedded within them,” she says.

Paired with her drawings is the installation “impossible monument (gilded)” that the artist made with fabricator Joel Kikuchi. A cabinet-like structure with singed wood supports holds keys strung on colorful ribbons. Peters wants viewers to contemplate forced exodus and displacement. “Often times people carry their keys because they believe they will go back,” she says. The entire cabinet is screened and has a backboard of laminated survival blankets. “From a distance, you see the work in full,” Peters says. “But the closer you get, it’s harder to see.”

“If people fully embrace a global perspective, then you own a slew of responsibilities for what’s happening in the world,” she adds. “It’s a heavy load. In sanctioned discussions about global displacement, there’s a patina of information that’s put on the story to deflect from the direness of it. I’m trying to make a work that is stunningly beautiful but is also honest about the vulnerability of loss.”

“impossible monument (gilded)” builds on years of Peters’ work exploring the notion of monuments. After a conversation with her sister, who worked in global radio, the artist became interested in how people all over the world manage to broadcast from their environments, even in conflict zones. She thought about how it might be possible to use and elevate material from those places to bring invisible histories into light. For the 2015 Out of Sight art festival, she created “impossible monument, (on my eyes and head)”—an ornamental carpet made from white flour that evoked food and famine. “If you have wheat, you can make bread and eat,” Peters says. “People were not understanding the destruction of farmlands in Syria, and the displacement of farmers to urban centers. It created a bread shortage.”

After meeting a nurse practitioner who consulted for Doctors Without Borders, Peters created “impossible monument (flotsam)”—a piece that responded to Yemeni fishermen needing advice for respectful ways to retrieve the belongings and remains of refugees lost at sea. The installation piece highlights the loss of personal belongings and effects. Embedded within the netting of “flotsam” are clothing and children’s stuffed animals, alongside lemons, a popular remedy for countering seasickness.

Peters came to the UW with a BA in printmaking from the University of California at Santa Barbara. She had worked in social services with her husband, running a group home for children in California. Peters’ sister Elizabeth married Cedric Robinson, an intellectual and scholar who wrote a pivotal 1983 work “Black Marxism” on black radical movements. The artist’s family and her professional and personal experiences informed her incorporation of sociopolitical concerns into her work. But at the UW, Peters made abstract drawings and paintings and was influenced by her contemporaries, who included Jeffrey Bishop, ’77, Preston Wadley, ’77, Dennis Evans, ’75, and Charles Luce, ’71. She credits Professor Michael Spafford for fostering her nerve. “He was so adamant that you need years and years of work,” she says.

Outside of the UW, Peters found inspiration and community at Triangle Studio, an experimental art space in the Prefontaine Building in Seattle’s Pioneer Square. Artists like Norie Sato, ’75, former UW faculty Bill Ritchey, Sherry Markovitz, ’75, Nancy Mee, ’75, Carl Chew and former UW student Lorna Jordan made and showed work at the studio, which Peters describes as at “the ground floor of video and performance.”

We’re living in an odd time of fear that makes it difficult to speak about calamity in a way that can be proactive, Peters says. “I don’t want people to walk away feeling guilty,” she adds. “I want them to walk away feeling that we live in a global community in which we are accomplices to all kinds of things happening in the world. You have to choose what you can address. My job isn’t to illustrate history. My job is to make something that’s compelling and curious—that make somebody look for the history.”

“the edge becomes the center” runs until January 5 at the Frye Art Museum. Admission is free. In 2025, the Whatcom Museum will mount a comprehensive retrospective exhibition of Peters’ “impossible monument” series.