It was not until his great uncle handed him a stack of old letters, 12 years ago, that Devin Naar, now an assistant history professor at UW, was able to begin filling in the gaps of his family’s history. Naar had known since he was a boy that he had relatives living in Greece during World War II. What he did not know was the fate that befell them.

His uncle’s letters proved to be the key to unlocking the mystery of this lost branch of his family’s past, but they were written in Ladino, the centuries-old Judeo-Spanish language of the Sephardic Jews. “It was in deciphering those letters that I was able to really get a picture of what happened to the Jewish community of Salonica [Greece] during the war and the murder of my relatives during the Holocaust,” says Naar, who holds the UW’s Marsha & Jay Glazer Chair in Jewish Studies housed in the Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies.

Inspired by his discovery, the professor is now leading a project dedicated to keeping the Sephardic language and culture alive. Ladino was originally spoken by the Jews expelled from Spain in 1492. When they migrated elsewhere, especially to what was then the Ottoman Empire, the language became a rich mixture of antiquated Spanish, Hebrew, Arabic, Turkish, Greek and other languages. As most Ladino-speaking Jews assimilated into other cultures or perished during the Holocaust, Ladino nearly died out.

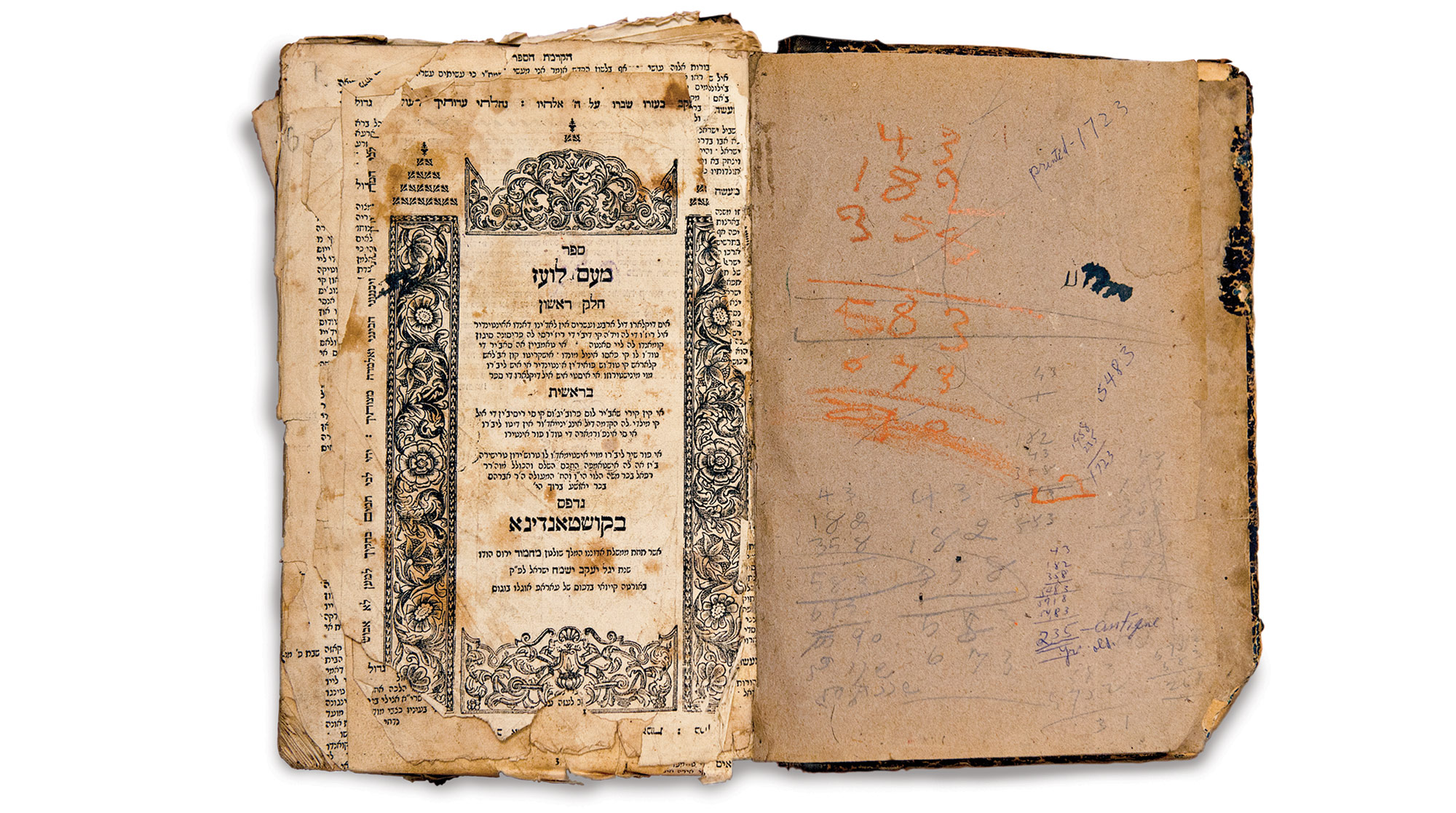

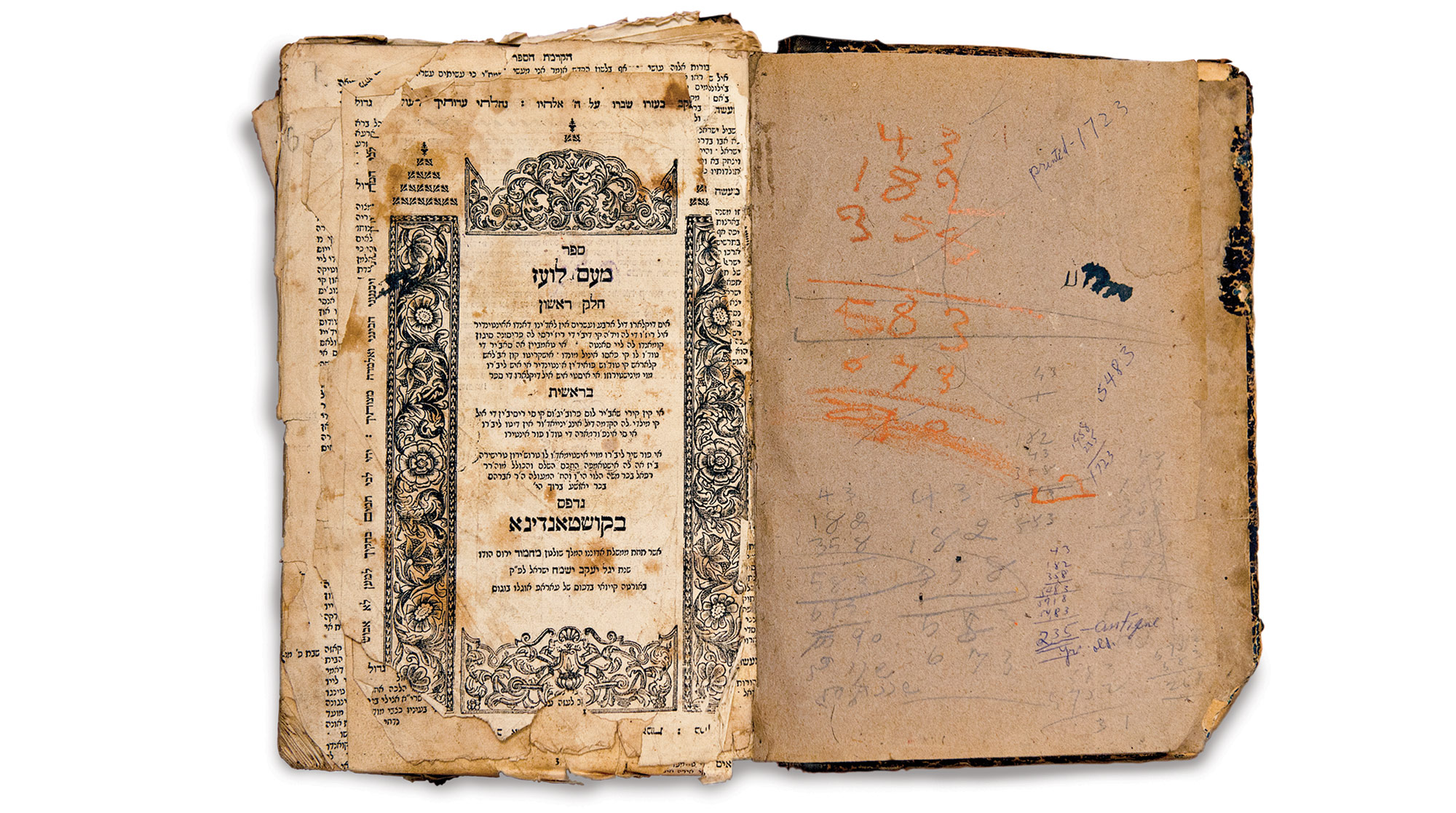

Cover of “Meam Loez,” published in Salonica, 1826. A key work of Ladino literature, this was one of the only books from Rabbi Naar’s library that survived, and was on of the first Ladino books Devin Naar ever saw. Pages from inside the book are pictured at top.

Growing up, Naar didn’t know much about the language, or just how endangered it is. Born and raised in New Jersey, he had picked up a few Ladino words from his grandfather, but was nowhere near fluent. But when he got hold of the family letters, he became fixed on decoding them. While his friends at Washington University in St. Louis would spend their Saturday nights going to parties, Naar would spend his teaching himself Ladino—a challenging task. When written, Ladino looks like Hebrew; when spoken, it sounds like Spanish. For example, the Spanish word for god is “dios,” while the Ladino word (spelled with Hebrew characters) is pronounced “dio,” an homage to monotheism.

After college, Naar spent a year in Salonica—the picturesque seaport city from which many of the mysterious letters had come—as a Fulbright Scholar, studying the city’s history and immersing himself in the languages, culture and hometown of his relatives. Following his travels, he received his Ph.D. in history from Stanford University in 2011. Under the tutelage of Aron Rodrigue—one of the few scholars of the Sephardic world—Naar won an award for his dissertation on the Jewish community of Salonica.

In the beginning, Naar could only make out the dates on the letters. But as he learned more Ladino, he was able to put them together piece by piece. Written between 1938 and 1950, many of the letters were correspondence between Naar’s relatives who had immigrated to the United States in 1924 and those who had remained in Salonica. The correspondence starts cheerfully, recounting the children’s piano and violin lessons, and one cousin’s preparation for his bar mitzvah. But as the clouds of World War II gathered, the letters took on a more ominous tone. Ultimately, they weave together the tragic story of Naar’s relatives who had remained in Greece and were unable to obtain visas out of the country. Those written after the war by a family friend divulge the fate of the cousin who had been preparing for his bar mitzvah; he was sent to the gas chambers instead.

The letters depict the dramatic final meeting between Naar’s cousin and great uncle at Auschwitz before they were both executed. They reveal that Naar’s relatives had been in one of the last convoys sent from Salonica to the Auschwitz concentration camp in 1943. The only reason they survived that long is because of his great-uncle’s job distributing food to the sick and elderly as they boarded earlier trains that transported most of Salonica’s Jews to their deaths in the gas chambers. Before the 1940s, Salonica was home to about 60,000 Ladino-speaking Jews, comprising nearly half of the city’s population. But with the onset of the war, some escaped to other countries, and 50,000 perished in Auschwitz. Only about 1,000 Jews remain in Salonica today.

“It was a real revelation. I couldn’t stop there,” says Naar. “I now have some precious knowledge about my relatives but that’s just one family of this entire world that, over the course of a few months, disappeared. Seventy years later, that world continues to be almost invisible.”

Salomon, Devin Naar’s great uncle, and his wife Esther perished in Auschwitz along with their two children, Benjamin and Rachel. They were captured in Salonica by the Nazis. This is the only photo of Salomon and Esther that survived.

After patching together his own family’s history, Naar was determined to help other Sephardic Jews do the same. In 2012, he launched Seattle Sephardic Treasures, part of the larger UW Sephardic Studies Program coordinated by the professor to preserve Sephardic traditions and culture.

The project is an archive of old Ladino books and documents that have been unearthed from basements and bookshelves from families in Seattle as well as others across the country. While it is still a work in progress, Naar has already collected more than 600 books with the help of local community members, students and faculty. The online database will contain everything from religious texts and diaries to newspapers and wedding invitations.

Joel Benoliel, ’67, ’71, a member of the UW’s Sephardic Studies Committee and Costco’s senior vice president and chief legal officer, calls Naar a valuable asset and a liaison between the University and local Sephardic community. “I’ve been a resident of the Seattle area all my life, and Devin’s work is the most exciting thing in my 50 years of being connected with the University,” he says.

The project took off when Naar moved to Seattle to teach at the UW in 2011. Uniquely, Seattle is home to a substantial population of Sephardic Jews, and the city has two Sephardic synagogues. Just a fraction (about 5 percent) of Jews who immigrated to the U.S. between the 1880s and the 1920s were Ladino-speaking Sephardic Jews, many of whom chose Seattle as their final destination to take advantage of the city’s coastal industries.

From the first fish vendors at Pike Place Market to the patrons of Benaroya Hall, Sephardic Jews have made a significant imprint on Seattle, which Naar calls a microcosm of the Sephardic-American world.

“When I arrived, people started bringing me Ladino books and letters that they couldn’t read themselves,” he says. “Then they started bringing me more things—a stack of documents here, a pile of books there.”

An ad for cigarettes made by the Turco American tobacco company from Devin Naar’s collection of Ladino artifacts.

Inspired by the community’s interest, Naar made an explicit call for Ladino documents. The response was overwhelming. Seattle Sephardic Treasures has now collected more Ladino books than are housed in the Library of Congress or Harvard University. Eventually, Naar hopes to upload audio recordings—some of which are more than 70 years old—to provide students, scholars and community members with an online resource for learning Ladino.

The project has three target audiences: university students, scholars and the community. “One of the really exciting things about the Sephardic Studies Program is that, at the university level, it can bring together many different programs and disciplines,” says Naar.

Al Maimon, a member of the UW’s Sephardic Studies Committee and a former professor at the Foster School of Business, says it was thrilling to meet someone so young who is concerned about preserving the culture. He calls Naar his kindred spirit.

“Before Devin came to town, the Sephardic studies dimension of the program was ad hoc,” says Maimon, who has contributed several heirlooms to the project. “When he arrived, that fundamentally changed. In Seattle, we have a living, breathing expression of Sephardic tradition. We’re custodians of a treasure. This isn’t just for us; it’s for the whole fabric of the Jewish community.”

Maimon believes that today’s Seattle Sephardic community is unprecedented. “There are few Sephardic communities that are as active, from a social, cultural and religious point of view,” he says. The challenge, he adds, is to reassimilate the traditions so families can pass them on to future generations.

“Saving a language is saving a culture,” says Wendy Marcus, ’76, music director at Seattle’s Temple Beth Am, a large reform temple in North Seattle. “At the rate we’re losing languages today, it’s nothing short of a mission on Devin’s part, and I applaud that mission.”

With the support and funding of the community, Naar has been able to do much more than collect dusty books. He has brought Sephardic musicians, photographers and guest speakers to the UW’s new Stroum Center for Jewish Studies, which, under the leadership of Professor Noam Pianko, is home to the Sephardic Studies Program. Naar has also organized a symposium with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. More than 1,600 students, faculty and community members have attended these events since last year.

Joel Benoliel, and his wife, Maureen, ’74, are part of the Sephardic Studies Program Founders Circle—a group of families that has committed to supporting the Stroum Center—and helped provide the seed money for the program along with Lela and Harley Franco, ’74. “With funds being cut from everywhere in the University, we need to make sure we can continue funding our programs that are so fabulous,” says Lela Franco, chair of the Sephardic Studies Committee. In addition to the Benoliels and Francos, the other members of the Founders Circle are The Isaac Alhadeff Foundation, Eli and Rebecca Almo, and Richard and Barrie Galanti.

“The people who have contributed to this project have made it possible; that’s the bottom line,” says Naar. “Without the support, enthusiasm and interest of our local community, Sephardic Studies would not be an initiative.”

The ultimate goal, he adds, is for the UW to become the nation’s center for Sephardic studies—a model for communities around the country. “I think it’s an important time to think about the future of Sephardic life, both in Seattle and in the United States,” Naar says. “The last generation of native Ladino speakers is on the way out, and a very rich and treasured past is slipping further and further into the distance.”

Two former UW Hazel D. Cole postdoctoral fellows in Jewish Studies were honored in the 2013 National Jewish Book Award competition. Maureen Jackson, ’02, ’08, a Cole Fellow in 2008-09, won the award in Sephardic Culture for her book Mixing Musics: Turkish Jewry and the Urban Landscape of a Sacred Song. Erica T. Lehrer, a Cole Fellow in 2006-07, was a finalist in the category of Modern Jewish Thought and Experience for her book, Jewish Poland Revised: Heritage Tourism in Unquiet Places.