Shirley Mahaley Malcom knew she would have her hands full. But it didn't matter. She was on a mission. She wanted to be a doctor.

Overcoming obstacles was old hat for her. Growing up in the racist South in the 1950s and 1960s, she learned all about adversity. Her mom’s church was bombed three times. And though she was the top student at her segregated, all-black high school, she knew going to college in the South was out of the question.

So she landed 3,000 miles from home at the predominantly white University of Washington, an affordable public institution with a medical school in a state that didn’t have racist practices mandated by law.

Having family in the Seattle area (an aunt and an uncle) eased her transition, but it didn’t prepare for her what lay ahead. Only a handful of black students attended the UW then. In her science classes, she was usually the only African American, many times the only woman, and always the only African American woman.

If that weren’t enough, she suffered the indignity of failing two freshman chemistry quizzes. She was so discouraged, she sought help from her teaching assistant.

“I told him that I wasn’t dumb, I was just having a really difficult time,” says Malcom, who, for example, had never laid eyes on chemistry lab equipment before coming to the UW. “I told him I needed some guidance, but that I could do the work. I knew I had the ability.”

“If someone says diversity isn't important, don't believe it.”

Shirley Malcom

The TA, a graduate student by the name of Ken Maloney, was himself African American, so he knew where Malcom was coming from. He lent an empathetic ear, and gave her the help she needed. The result? She aced her next quiz.

“If someone says diversity isn’t important, don’t believe it,” Malcom says.

That one experience helped shape a career that has benefited thousands upon thousands of people—not as a doctor, but first as a teacher and now as a national leader in making sure women and ethnic minorities don’t have the same hardships in science she did.

Employing the skills she developed as a high-school and college teacher—using innovative approaches, getting people to work together and looking at the big picture—she took her lesson plan to the highest levels, teaching a nation that women and ethnic minorities were getting the short end of the stick when it came to science education, and then going about fixing things. At the American Association for the Advancement of Science and as a member of the National Science Board, she has brought science education to thousands and thousands of students who otherwise would not have had the opportunity. For her work, the University of Washington and the UW Alumni Association have bestowed upon her their highest honor: the 1998 Alumna Summa Laude Dignata Award.

“She is a pioneer who has not only has authored milestone reports but brought this issue to national attention,” says Karl Pister, a former dean of engineering at Cal-Berkeley. “She is a wonderful role model, and the changes we are seeing are directly the result of her unwavering pursuit and dedication.”

The issue she tackled couldn’t have been larger. Though African Americans make up 12 percent of the U.S. population, they receive only three percent of the science and engineering doctorates in a given year. Low participation rates also apply to Hispanics and Native Americans. And while women have made strides, they are still underrepresented in engineering and some of the physical sciences.

No wonder it was so rare for Malcom to encounter an African American science teacher when she was a student.

“It was downright dismal,” explains Willie Pearson Jr., a Wake Forest University sociology professor and an expert on science education for women and minorities. “I grew up in a part of Texas with historically black schools where we had black professors and college presidents. But when I left the area, I couldn’t find any black professors or blacks in science industry.”

But Malcom wasn’t thinking about that when she was a little girl growing up in Birmingham. The daughter of a meat packer and school teacher, she loved biology and wanted to be a doctor.

Though Seattle was a relief because racism wasn’t as prevalent as in the South, “I had lived in an all-black world in Birmingham,” she says. “I had very little interaction with people who didn’t look like me.”

Malcom—one of only three African American out of 400 women in her UW dorm at the time—lived with white roommates for her four years here. Her first roommate was from North Dakota and had little experience with blacks. “We focused on things we had in common: getting through chemistry, music, going to games.” They also talked about their wildly different times growing up.

It was an education for both of them. “This is the reason we must recognize and defend the educational value of diverse learning communities,” she says.

She also had difficult times. One friend in the dorm had a boyfriend who made little effort to hide his dislike of blacks. And it was hard for her connect with black students who commuted to school. “I was a Southerner, with a lot less `polish,’ and likely a lot more baggage than Seattle-born students,” she says. “And as a science major, I was already a world apart.” She spent so much time in labs, she didn’t have time to get involved with African American commuter students. “I often felt isolated from that side,” she recalls.

In the UW classroom, she learned another hard truth: “I found out how deficient segregated schooling left me,” she recalls. “I was the top student in my class in high school, but at Washington I had to run like crazy in my studies to keep up. I just had to work harder than anyone else around me. I knew it was going to be unforgiving. I knew a lot of sacrifices were being made so I could be in college.”

When she wasn’t in class or a lab, she was usually holed up in a favorite corner of Suzzallo Library, studying. About her only regular social activity at the UW was serving a year as a dorm representative on the ASUW Board of Control.

John Coombs, associate vice president for medical affairs at the UW, was a fellow zoology major. “She was a very good and hard-working person, while at the same time a very warm and interactive individual,” he recalls. “She always had concern for her fellow classmates, and was quite confident about her own abilities, especially as time went by.”

But the ones who had confidence in her abilities were her professors. Between her junior and senior years, Zoology Professor Alan Kohn, Malcom’s adviser, was so impressed with Malcom that he suggested she consider a science career in academe—a field with few African Americans. “Had he not said that, I don’t think I would ever have thought of myself in that role ever,” she says. “He saw my potential.”

She continued into uncharted waters. After graduating from the UW, she was off to UCLA, where she earned a master’s degree in animal behavior in 1968 and got involved with civil rights marches, occupations and strikes. After that, she thought she found her niche, teaching high school in Los Angeles. But the 1971 earthquake and the murder of a cousin in Southern California devastated her. So she moved back to Seattle for a year, where she served as the director of Hansee Hall at the UW.

She enjoyed being back. But she realized, “I was leaving my dream unfulfilled,” she says. “I needed to get back into education.” Off she went to Penn State, where she received a Ph.D. in ecology. Following graduation, she got back into teaching, accepting a faculty position at the University of North Carolina-Wilmington.

A year later, she met the man who would become her husband, Horace Malcom, a physicist, and they moved to Washington, D.C. She hated to give up teaching and being a role model for her students, but landed a job as a research assistant at the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Her first assignment: an inventory of programs in science for minority students.

For the first time, Malcom realized the magnitude of what she and other ethnic minorities (especially women) had been up against her whole life. Science education programs—run mostly by white men—often excluded minorities. And those that were set up to serve minorities favored men.

That led to a 1975 landmark report, “The Double Bind: The Price of Being a Minority Woman in Science.” In it, Malcom documented that minority women were the victims of two problems: racism and sexism. The biggest outrage: educational programs geared toward minorities gave preference to men. She also found that the few minority graduate students or professors in academe weren’t often incorporated into each department’s culture.

“These issues were not part of the national agenda 15 years ago,” says Angela Ginorio, a UW sociology professor and director of the Northwest Center for Research on Women.

So Malcom devoted herself to trying to make things right. As head of the AAAS Directorate since its establishment in 1989, Malcom—who manages a staff of 50 and an annual budget of $6 million—developed a wide array of programs advancing education in science, mathematics and technology at all levels, improving public understanding of science and greatly expanding the talent pool.

But like much of her life, it didn’t come easy. Since traditional education wasn’t doing the job, she wanted to go “outside the box” and reach out to minorities in their communities. She wanted to find other ways to teach science. She hit resistance at every turn, from people not liking her ideas to not having enough resources to carry them out.

“My views about providing access to science for all were a hard sell for a while,” she says. “Not everyone has agreed with the necessity of getting communities and parents directly involved inthe stuff of education reform.”

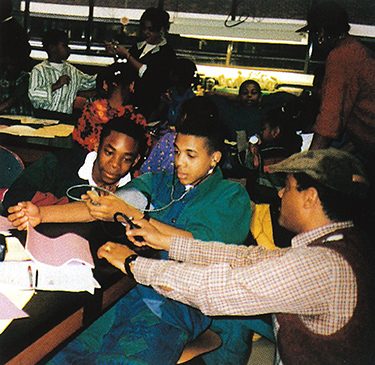

As many as 50 children turn out on Saturday mornings for science projects at Seattle churches as part of the Black Churches project started by Shirley Malcom. Photo courtesy Millie Russell, UW Office of Minority Affairs.

Among her innovative programs is the Black Churches Project, which uses churches and church networks across the nation to bring science, environmental and health education to African American communities. Another is Proyecto Futuro, which connects science learning in the school, community and home by creating bilingual materials and demonstrating links between science and the Latino culture. She is also busy overseeing Kinetic City Super Crew—a radio adventure series with on-line, club and classroom outreach—as well as Earth Explorer, a CD-ROM multimedia encyclopedia of the environment.

She also holds workshops for teachers, has set up a network of deans at major research universities, and works with government leaders to secure enough science money for schools.

“She is as involved with driving policy from the top as she is with making certain her programs are heavily invested at the grass-roots,” says Catherine Gaddy, executive director of the Commission on Professionals in Science and Technology.

There is no better example than the nine Seattle churches where the Black Churches Project holds court on Saturday mornings. It isn’t unusual for 40 or 50 neighborhood kids to turn out for science classes in the basements of such local churches as Bethel Christian and Greater Mt. Baker Missionary Baptist.

“The kids really get into it,” says Millie Russell, assistant to the vice president of minority affairs at the UW and the local contact for the nationwide project. “There is so much interest in our neighborhoods that has gone untapped. Children love science projects, and we have to get the community involved even more.”

Another creative idea of Malcom’s was having high-school students tutor younger children in science. That was the cornerstone of a community science project funded by the Readers Digest Foundation. “It was effective because it showed that kids of all ages are very interested in science,” says Terry Russell, executive director of the Association for Institutional Research. “Now the aim is to get parents involved.”

Malcom never stops aiming high. She received the Reginald H. Jones Distinguished Service Award, the highest honor given by the National Action Council for Minorities in Engineering, in 1997 and directed the $10,000 prize to teachers in the beleaguered District of Columbia school system.

But grass-roots are only part of Malcom’s approach. In addition to serving on the National Science Board, she is on the President’s Committee of Advisors on Science and Technology and was chair of a task group studying labor and education issues for the Clinton transition team.

Shirley Malcom confers with President Bill Clinton and Vice President Al Gore during a meeting of the President’s Committee of Advisors on Science and Technology at the White House. White House photo.

Malcom “has been a leader of championing the importance of ensuring that all students receive an outstanding science education,” says UW Engineering Dean Denice Denton, the first woman dean of engineering at a major U.S. research institution. “Her work in explaining the importance of diversity in the science, math and engineering workforce has been pivotal.”

But devoting herself to having that kind of impact has come at some personal cost. “What makes you think I ever unwind,” she asks with a smile. “I have to work at it.” Though she traveled a lot when her two daughters were young (they are now students at MIT and Duke), she says, “When my daughters needed to carry in the birthday cupcakes, I always baked. That was my penance.”

Things are better now, but there is still so much to do in the push for science education for all, especially with new efforts to turn back affirmative action.

“Convincing people that we can all get further if we work in partnership on solving our education problems in this country continue to be a challenge,” she says. “And the assault on programs to bring access to quality education in science, mathematics and technology to all makes me feel that I am starting where I began.”

But Malcom has never been one to give up. She didn’t give up when she failed her chemistry quizzes, and she isn’t about to now.

“The opportunity to reverse those trends are at hand,” Malcom says, referring to data suggesting that interest in pursuing science and engineering majors is growing among minority freshmen.

“The next generation of science must necessarily draw on young people who are not generally see (and indeed often do not see themselves) as being in the present mix,” Malcom wrote in a major piece for Scientific American. “Who will do science? That depends on who is included in the talent pool. The old rules do not work. It’s time for a different game plan that brings new players off the bench.”