Sick &

tired

Sick &

tired

Sick &

tired

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, unfairly labeled “yuppie disease,” is no joke. The mysterious malady can attack anyone from 5 to 75, UW researchers warn.

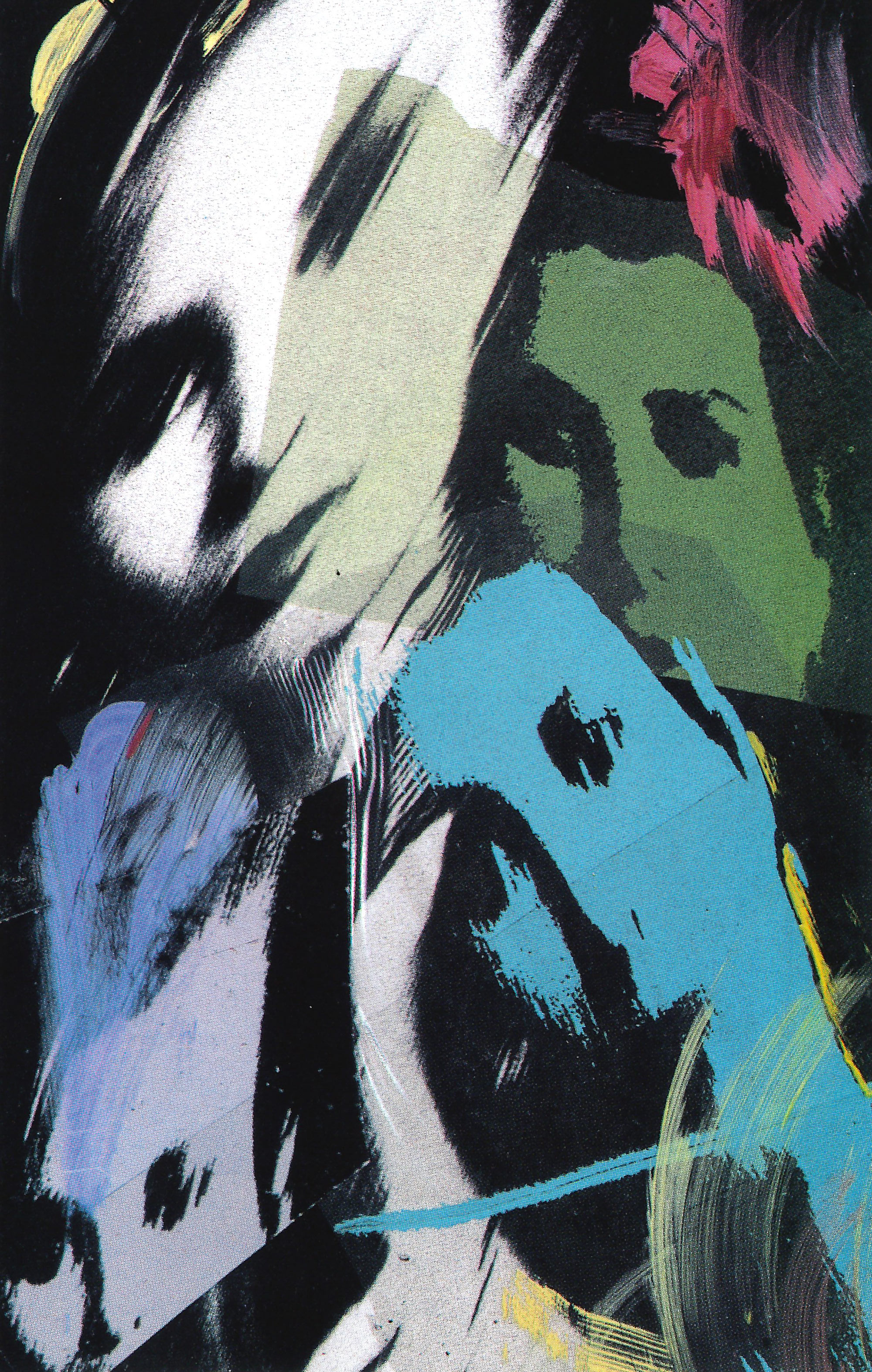

By Jean Reichenbach | Illustration by Ken Shafer | Dec. 1990 issue

At some point during the first four years of an illness which she describes as feeling like "the absolutely worst case of flu imaginable that never goes away," Cathryn Morgan faced the chilling possibility that she might live with nausea, dizziness, mental confusion and disabling fatigue for the rest of her life.

Morgan suffers from Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) a debilitating illness that has been inaccurately tagged “yuppie disease” or “yuppie flu.”

“Over a period of time, you know you won’t die and you realize that this is what life may always be like,” reflects the 48-year-old mother of three.

The mysterious disease struck Morgan in November 1986. She arrived at work one morning feeling normal and went home, only hours later, shaking, dizzy and mentally confused. At first, she wondered if the puzzling change was a panic attack. Her doctor suspected a small stroke. A possible inner ear problem was considered and rejected. At one point Morgan feared Alzheimer’s disease. “I felt like my head was full of mush,” she recalls.

To be considered a possible victim of the disease, debilitating fatigue must last at least six months and reduce normal activity by more than 50 percent. “It is not just being tired,” points out Dr. Dedra Buchwald, assistant professor of medicine and director of the Chronic Fatigue Clinic at Harborview Medical Center, a UW affiliated hospital.

Dr. Dedra Buchwald

Other symptoms—which vary widely from patient to patient—include mild fever, aching muscles, headache, sore throat, muscle weakness, painful lymph nodes, mental confusion, sleep disturbance and depression. The condition is not detectable from laboratory tests. For the most part, physicians must rely on patient descriptions of how they feel.

The degree of disability varies widely. Some victims can continue working, providing they curtail outside activities. Some must switch to part-time or temporary jobs. Some must stop working all together. Others, fewer than 20 percent, are bedridden, says Buchwald.

Although the disease was formally defined only as recently as 1988, a similar affliction was described by the Chinese several thousand years ago, Buchwald notes.

Reports of CFS-like illness have appeared in the scientific literature for more than a century, according to the Centers for Disease Control. A 1985 epidemic-like outbreak of more than 400 cases in the Lake Tahoe area produced a surge of interest in the disease, Buchwald says. “Cluster” outbreaks have also been reported in Iceland and Los Angeles in the fairly recent past.

But “most, most, most” cases are isolated instances and not contagious even among close family members, stresses Buchwald, who offers two possible explanations for occasional cluster outbreaks. Several viruses, either alone or in combination, probably cause the syndrome and, in some instances, the responsible virus may be contagious, she explains. Or, she adds, cluster statistics may reflect the increased number of cases identified simply because an investigator is actively looking.

Although most reported cases involve people 30 to 50 years of age, the malady is not a “yuppie” disease. Buchwald has seen cases “from kids to people (who are) 75.” Relatively affluent baby boomers are simply more health conscious, and, therefore, more likely to consult a physician. “That applies to all diseases,” she adds.

Most of the approximately 400 patients Buchwald has seen in her clinic are women and almost all are Caucasian. But minorities enjoy no special protection, she adds. “It’s just not in their repertoire to seek help for these kinds of problems.”

The typical victim who seeks medical help is a Caucasian female, 35 years old, who works full time and is happily married. She enjoyed good health and an active lifestyle until she succumbed to a flu-like illness from which she has “basically never recovered,” in Buchwald’s words.

Symptoms tend to wax and wane over time, perhaps matching the rise and fall of stress in the patient’s life or marking those times when she overestimates her capacity for increased activity. Typically, she’s seen several physicians but received no satisfactory diagnosis or treatment. Often she will be sickest during the first year and then slowly recover over subsequent months or years. Some victims, however, have been afflicted for as long as 30 years.

“I went from a normal person to a person who could literally do nothing.”

Cathryn Morgan

Morgan fits that profile in many respects. A Bellevue resident, prior to her illness she worked as a receptionist in preference to full-time homemaking. The disease forced her to give up her job. Only last March did she feel well enough to return to part-time work.

For Morgan, the worst period began in November 1987, one year after onset, and lasted into the following spring. She was losing weight, plagued by aching muscles, and sleeping 18 hours a day. “I would wake up shaking from head to toe and think ‘Is this ever going to stop?’ ” she recalls. Dizziness made riding in a car uncomfortable and driving out of the question. Poor concentration made reading impossible. “I went from a normal person to a person who could literally do nothing,” she says.

Although chronic fatigue has been listed as one of the 10 most common reasons for consulting a physician, the number of Americans who suffer from the disease is unknown. Buchwald, in conjunction with Group Health, recently surveyed fatigue in 4,000 people selected at random. The response astonishes her. Of the first 3,500 survey forms returned, 450 respondents described symptoms that matched CFS warning signs—fatigue sufficiently severe to reduce normal activities 50 percent or more and lasting at least six months.

So far, the cause eludes detection. Buchwald and others suspect a virus or several viruses. Initial suspicion fell on Epstein-Barr, a herpes virus which causes mononucleosis. But subsequent research failed to support that theory.

A UW research team recently used radioactive DNA to look for the DNA of the Epstein-Barr virus in the blood and saliva of 26 patients suffering from prolonged chronic fatigue (who also had high levels of antibodies to the Epstein-Barr virus) and 18 healthy people. Researchers, which included Professor of Laboratory Medicine Lawrence Corey and Dr. Wayne Katon of the Department of Psychiatry at the UW Medical Center, found that the frequency of Epstein-Barr DNA in blood and saliva were similar in the two groups.

“The bottom line is that we don’t have enough information to say ‘This is the cause, “‘ Buchwald says. She is confident, however, that CFS has no link to AIDS. “It’s disabling but not fatal, ” she explains. “Most patients get better, not worse.”

Another mystery is the link between depression and chronic fatigue syndrome. Corey and Katon, for example, found that 42 percent of the chronic fatigue patients suffered from depression, many of whom recovered without treatment, Corey says. In a recent issue of Science, British researcher Peter White, of London ‘s St. Bartholomew ‘s Hospital, said 75 percent of his CFS patients are clinically depressed.

Buchwald finds measurable clinical depression in about 25 percent of her patients compared to less than 5 percent in the general population. Her numbers are lower than many other studies because of the rigorous criteria she applies before deeming a patient clinically depressed. White told Science he believes depression is a cause—although not necessarily the only cause—rather than a consequence of the disease, citing preliminary studies which show marked improvement in chronic fatigue patients treated with an anti-depressant.

Buchwald and Corey are less certain about cause and effect. Depression can suppress the immune system, which can then open the door for the mysterious disease , Buchwald points out. “But it can go the other way. Any normal human being who is chronically fatigued could become depressed. But either way, it’s important.”

Buchwald hesitates to overplay the role of depression because, at least in the past, some physicians have used depression as a convenient label for an ailment that defies objective diagnosis. The message to some patients has been “You’re a crock,” Buchwald points out. But that is changing. “Patients tell me that their doctor thinks they may have ‘something,”‘ she says. The referring physician may not know what the “something” is but acknowledges that it’s there. That fits Morgan’s experience with her physician. “My doctor never acted like I wasn’t sick,” she recalls.

With no definitive tests to fall back on, diagnosing the disease becomes a process of ruling out other possibilities, such as sleep apnea or thyroid problems, Buchwald says. That done, all she can do is treat the symptoms. The anti-depressant drug Prozac is helpful, she observes. Anti-depressants work well with most patients, whether or not they are clinically depressed. “It seems to make them more awake, ” she observes. All drugs are prescribed in low doses, however, because most victims are exceptionally sensitive to medication.

Buchwald also recommends common sense changes in lifestyle and increasing exercise as strength returns. For many victims walking around the block is an achievement, she points out. Others can manage no more than stretching exercises at first.

Morgan made it a point to get out of bed, shower, wash her hair and put on makeup before 11 a.m., even when the effort left her so exhausted she immediately went back to bed. Gradually, as her mind began to clear, she read simple newspaper stories, did jigsaw puzzles and, later, crossword puzzles . Her physical exercise advanced from walking the length of the hallway, then to the front door, and then outside and all the way down the block. Today, she walks two or three miles a day.

Morgan believes her condition improved when she, in her words, “quit actively looking for a cure” and accepted the fact that she may never be entirely well.

Today, her sense of balance remains imperfect but she is steady enough to wear moderately high- heeled shoes. She still experiences dizziness and often returns from her part-time job exhausted. Residual mental confusion—not a trace of which is detectable in her conversation—has taught her to conscientiously double check her work and she freely acknowledges her limitations. “I wouldn’t do anything that requires a lot of memory,” she says.

Life for Morgan is “not as good as before but acceptable,” she says with an upbeat tone. “I’m leading a decent, good life and I’m used to being sick.”