On the paternal side of Carver Gayton’s family, no one broached the topic of slavery in Yahoo County, Miss. “My father’s father left the Deep South, never to return in either word or deed,” says Gayton, a renowned civic leader and former football star. “It was a place of unspoken shame, slavery, and later, of sharecropping.”

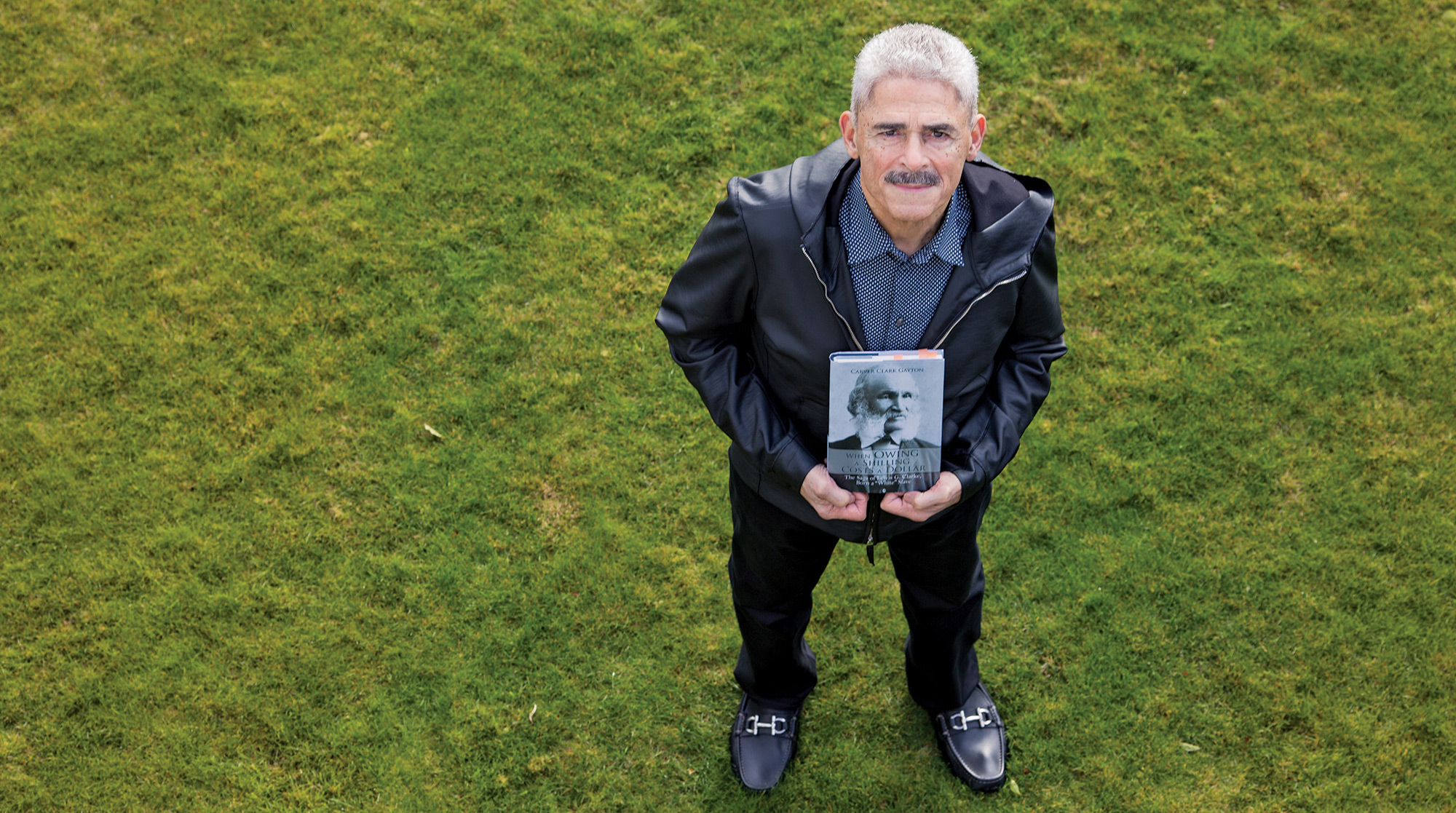

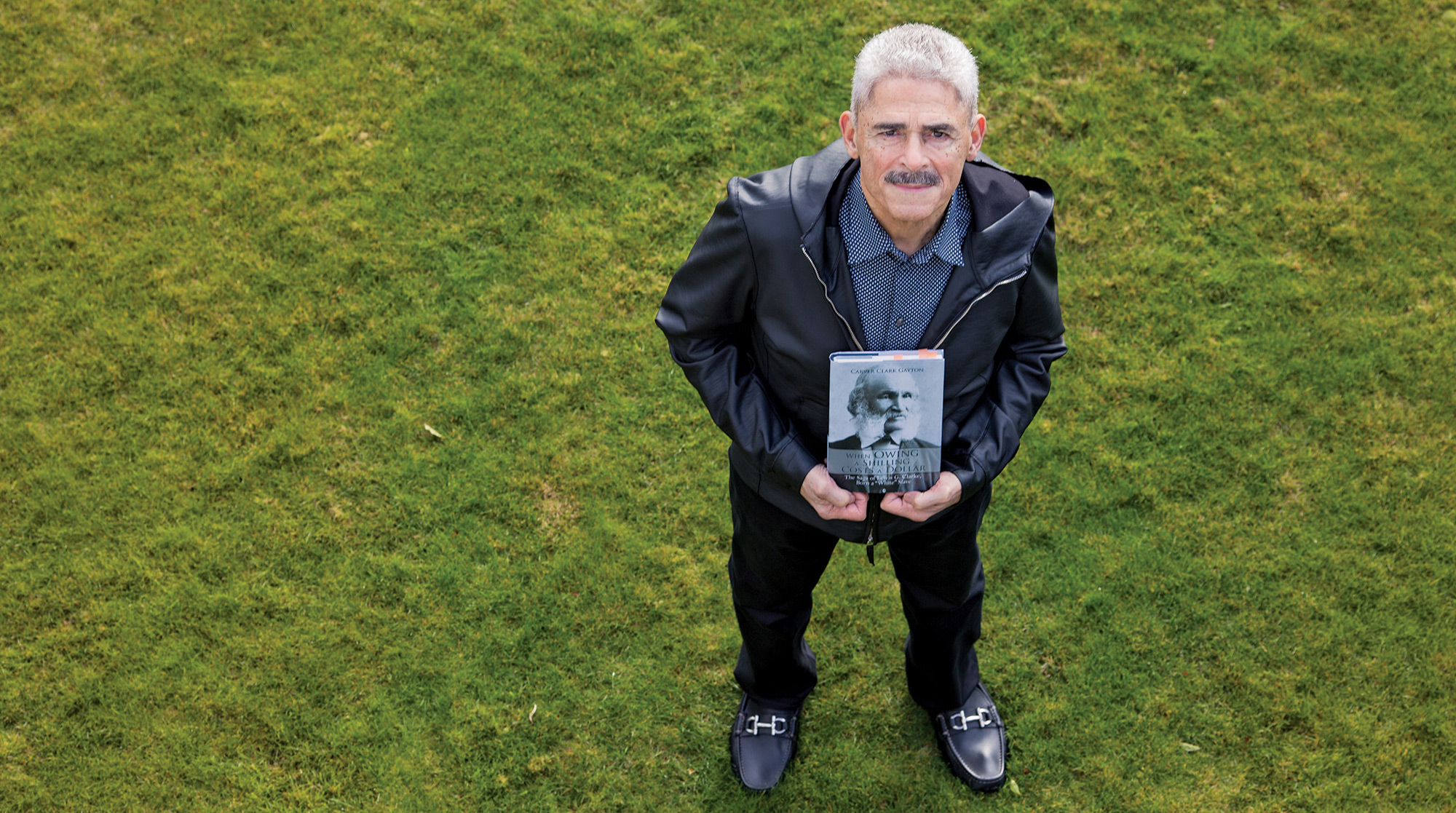

But his mother took a different tack. She spoke often and with pride about her grandfather, Lewis G. Clarke, who escaped slavery and went on to become a leader in the abolitionist movement. Moved by her stories, Gayton, ’60, ’72, ’76, published a gripping 2014 biography of his great grandfather, When Owing a Shilling Costs a Dollar: The Saga of Lewis G. Clarke, Born a “White” Slave. The book debuted soon after Gayton worked with UW Press to republish Clarke’s 1845 autobiography, Narrative of the Sufferings of Lewis Clarke.

“My study of Clarke was really a lifelong effort,” says Gayton, now retired after founding and serving as executive director of the Northwest African American Museum. Gayton’s mother also introduced him to a volume called The Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin. In it, author Harriet Beecher Stowe names Lewis Clarke as the prototype for George Harris, the rebellious, clever slave in her more famous book, Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Born into bondage in Kentucky, Clarke was separated from his family at the age of 6. Twenty years later, he grabbed a horse and fled for points north. He eventually reached Massachusetts and Canada, where he spent the next two decades as a free man. Even in the North, he faced ongoing prejudice. Attending church in Cambridgeport, Mass., for instance, meant sitting in the “Negro pews.” But the bigotry didn’t stop Clarke from working for the rest of his life to end slavery. Gayton’s biography gives Clarke long-overdue credit for helping people escape captivity via the Underground Railroad. In the 1840s and ’50s, he delivered more than 500 speeches urging abolition, often sharing the platform with famous figures of the movement: Harriet Beecher Stowe, William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass.

Although the story of Lewis Clarke—who died in 1897 at the age of 82—is often wrenching to read, it carries a message of hope. And that was Gayton’s intention all along.

“One thing I’m concerned about with young black males is that they will give up,” Gayton says. The publication of Clarke’s story proved to be one of the most meaningful projects Gayton has ever undertaken. And that’s saying something, given the 77-year-old Seattleite’s track record as one of Western Washington’s most dedicated public servants. A graduate of Garfield High School, Gayton was the first black FBI agent in Washington (1963) and UW’s first full-time black assistant football coach. This great grandson proudly carries on as a living legacy of Lewis G. Clarke.