Chihuly’s

world

of glass

Chihuly’s

world

of glass

Chihuly’s

world

of glass

For his distinguished career in the arts, Dale Chihuly, ’65, is the 1993 UW Alumnus Summa Laude Dignatus.

By Tom Griffin | June 1993 issue

He's the foremost glass artist of his generation, the founder of the Pilchuck Glass School, one of only three American artists to ever mount a solo exhibit at the Louvre, and recently the set designer for the Seattle Opera's landmark production of Pelleas et Melisande.

For his distinguished career in the arts, Dale Chihuly, ’65, is this year’s UW Alumnus Summa Laude Dignatus, the highest honor the University can bestow upon any graduate.

Yet in the early 1960s, when Chihuly left his hometown of Tacoma to start at the UW, few would have predicted these later honors. “I was a mediocre student,” he confesses. He describes his fraternity—Delta Kappa Epsilon, a.k.a. the “dekes”—as “an animal house, the wildest fraternity at the U.”

But in the middle of his college years, Chihuly abandoned the “animals” for a year off in Europe. He returned a different person.

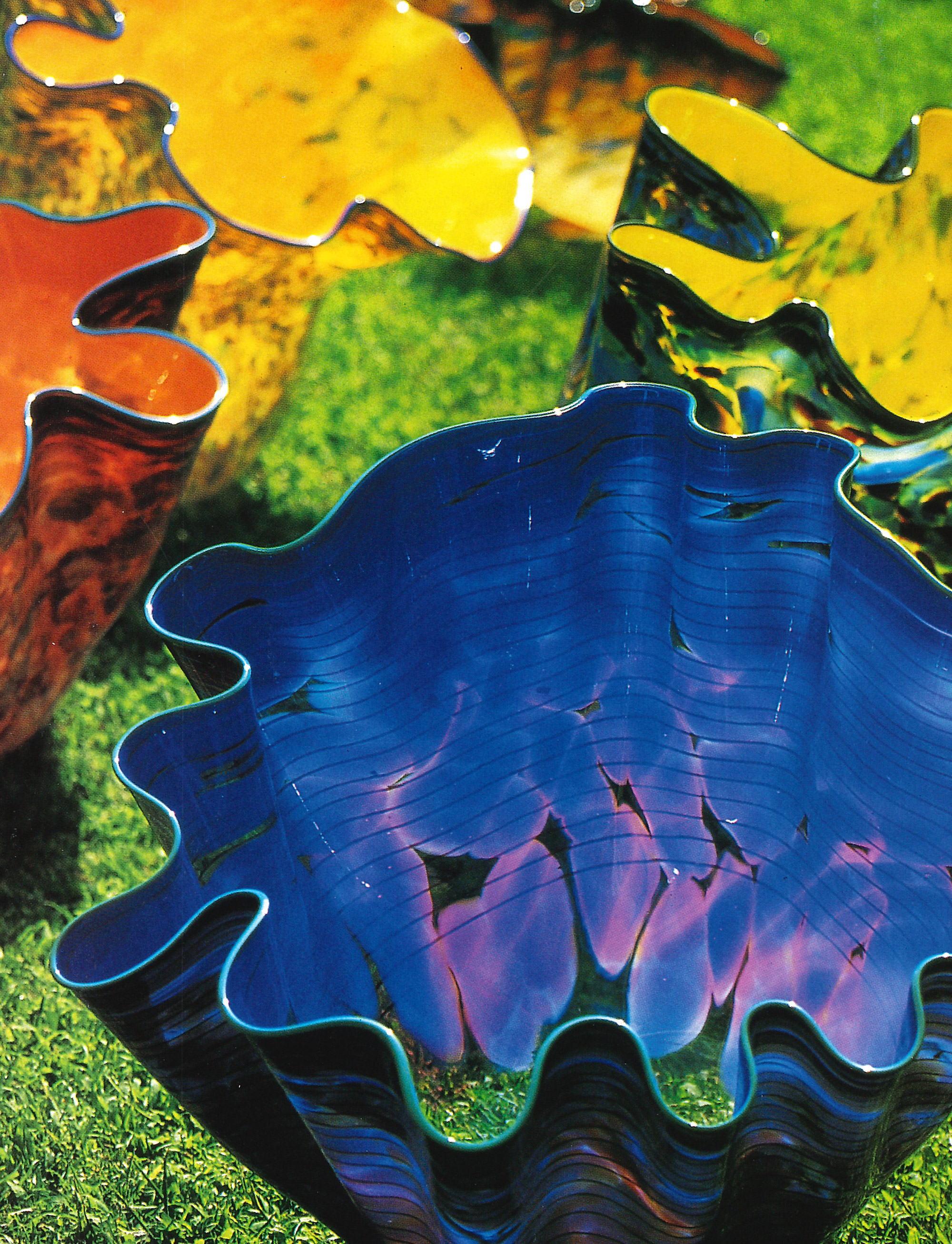

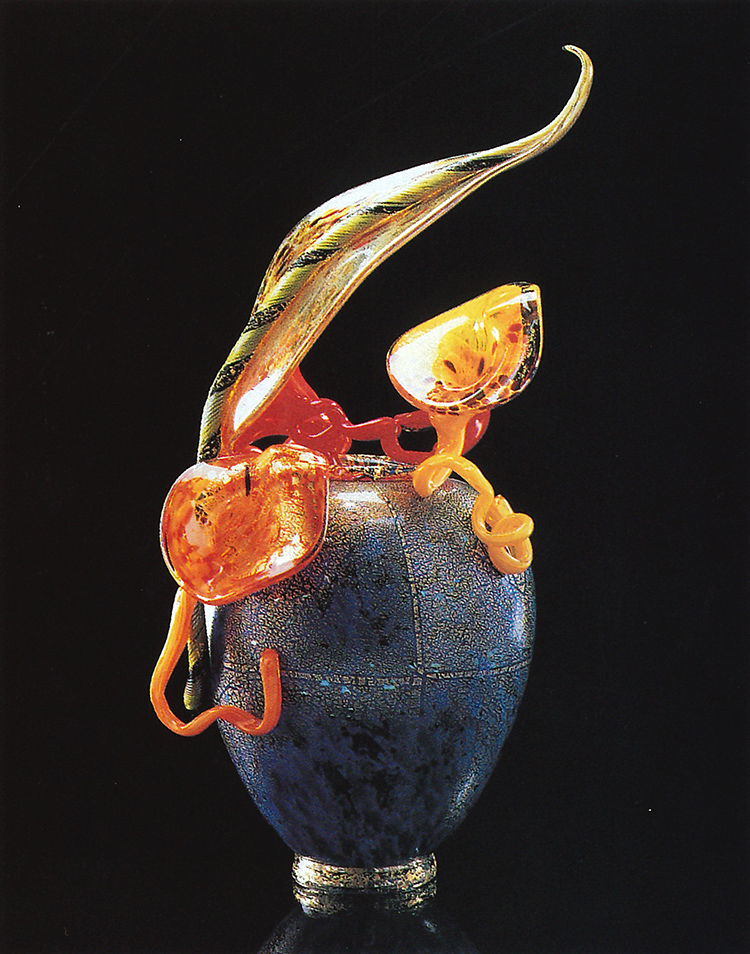

Yellow Venetian with Vermillion Handles, 1993. Photo by Claire Garoutte. At top: a detail from the Macchia installation outdoors at the Honolulu Academy of the Arts, 1994. Photo by Russell Johnson

“When I came back, I never set foot in the fraternity house again. I became the ideal student,” he recalls.

Taking advantage of such influential UW art teachers as Doris Brockway, Hope Foote, Warren Hill and Steven Fuller, Chihuly became a fixture in the art building. Working till midnight, he wouldn’t bother to go home. Instead he headed for his ’49 Hudson parked in a campus lot, which had a mattress for a back seat.

Art Professor Steven Fuller introduced him to glass in a design materials class. Students were required to do projects in glass, metal, wood or other materials and Chihuly made a glass panel. “He was a good student,” says Fuller. “But his habits were very independent. He wouldn’t always come to class, but he’d get his projects done.

I gave him a ‘B.’ I’m sure he expected an ‘A.’ “Asked how he would grade Chihuly’s current work, Fuller immediately responded, “Oh, ‘A’ with several pluses.”

In a textile class taught by Brockway, one assignment was to weave something “other than fabric” into a tapestry. Chihuly chose glass as his material, and that deepened his devotion to glass. After his UW graduation, he spent a year working as an interior designer at a Seattle architect’s office. During his off-hours he taught himself to blow glass.

Sea Form installation at the Seattle Art Museum, 1992. Photo by Eduardo Calderon.

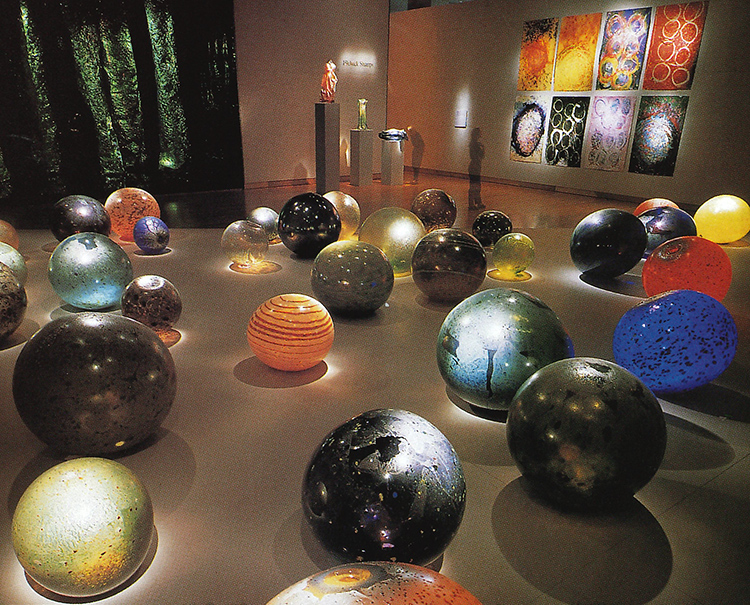

Niijima Floats installation at the Seattle Art Museum, 1992. Photo by Eduardo Calderon.A fellowship to the University of Wisconsin led to his work with a pioneer of the studio glass movement, Harvey Littleton, who had developed new techniques and materials that made glass blowing easier in a small studio. Later Chihuly would move to the Rhode Island School of Design, where he earned an M.F.A. and taught.

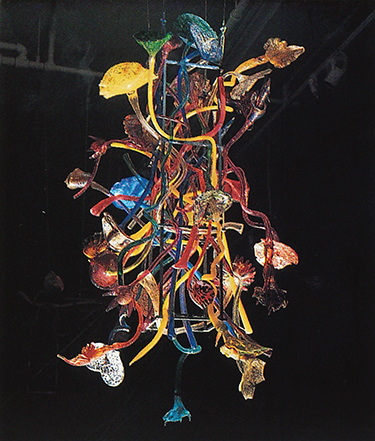

It took him 10 years to sell his first work of art. Today his work is in demand from Tokyo to Tacoma. A small piece might sell for around $6,000; a signature piece such as a Macchia could go for $22,000; while his newest explorations in glass—chandeliers, go for $200,000 to $300,000.

Chandelier, 1992.

Photo by Claire Garoutte.

These artworks are spontaneous combustions: glass heated to the melting point then rolled in colored “jimmies,” glass fibers or some other material to give the glass its hue. The glass is reheated and molded into extraordinary forms: baskets, cylinders, spotted open vessels called Macchia or elaborate glass pieces decorated with cherubs or lilies.

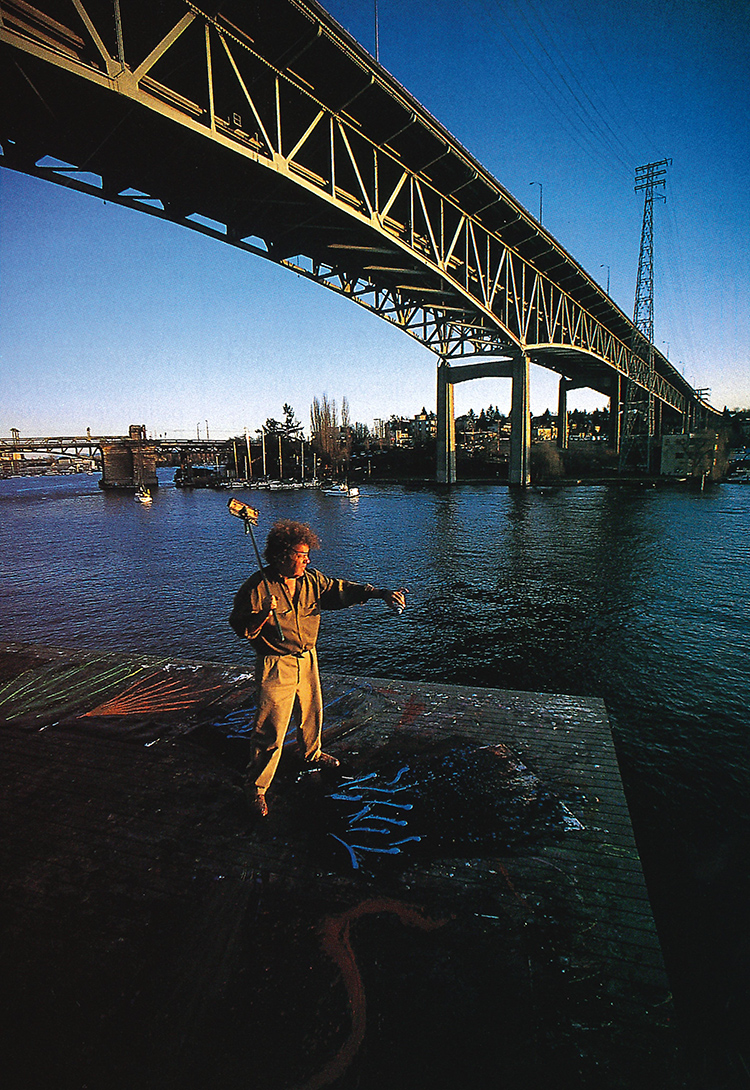

It’s all done just a stone’s throw from the campus where he began his artistic career. Chihuly’s workshop is the old boathouse of crew legends George and Stan Pocock, located under the I5 Ship Canal Bridge on the waters of Lake Union. Two Pocock wood shells hang from the ceiling of his display room.

Stepping inside the workshop is like taking a high speed trip to Hell. Heat, hot gases and intense, bright flames greet you as you enter. No matter what the weather, Chihuly’s assistants, dressed in cutoffs and T-shirts, look like they’re ready for a summer’s jog.

The workshop is crucial to Chihuly’s art. The artist himself has not crafted a piece by himself since a 1976 traffic accident took the sight from his left eye. Instead, Chihuly directs the production of his artwork while his team executes the design.

While they start from a drawing by Chihuly, fate and inspiration often intervene, and the planned design becomes a spontaneous creation that may end up on a collector’s table, in a new Seattle skyscraper or as part of the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of New York.

Cobalt Blue and Gold Venetian, 1990. Photo by Roger Schreiber.

Chihuly stands on the roof of his Lake Union workshop trying out designs for his opera production. The girders of the Ship Canal Bridge soar above. Photo by Russell Johnson.