Stolen beauty Stolen beauty Stolen beauty

The story of the shocking theft, destruction and replacement of George Tsutakawa’s sculptural gates at the Washington Park Arboretum.

By Mayumi Tsutakawa | June 2022 issue

“The antique bronze gates, subdued in the reflected sunlight, are cunningly designed but so sturdily built as to resist time and its erosion,” noted a 1976 issue of the Arboretum Bulletin covering the installation of the Arboretum Memorial Gates designed by UW Professor George Tsutakawa, a noted American sculptor.

In fact, my father expressed the idea that the sturdy bronze material he used for dozens of sculptures and fountains could last for hundreds of years. Instead, the Memorial Gates, which sat near the north entry to the Washington Park Arboretum at the Graham Visitors Center, were destroyed almost 45 years after they were lovingly installed and dedicated. One night in March 2020, at the start of the pandemic, thieves cut through the supports and quickly loaded the two heavy gates, 20 feet wide in total, into a truck to be hauled away and sold for scrap. The vandalism and theft shocked the neighborhood as well as the UW community and Arboretum volunteers. The entire Tsutakawa family and Arboretum staff reacted with surprise, dismay and perhaps a bit of anger, that a work of art lovingly created by our father, George, was obliterated.

George Tsutakawa created more than 75 fountains and sculptures, many of which are still on view in public spaces in North America and Japan.

The Seattle Police Department, savvy to metal theft, one of the fastest-growing crimes in our region, quickly recovered the cut-up pieces of gate through detective work and a bulletin to scrap metal dealers. The thieves had tried to sell some of the bronze to a local recycling business. One gate had been destroyed and the other significantly damaged.

Sadly, the pieces could not be put back together. According to my brother, Gerard Tsutakawa, who helped fabricate the original gates when he was a young metalsmith, the design is so intricate, involving branches of bronze that curve inward in two dimensions, there was no hope for repair. “My reaction to the theft was shock,” he says, “pure miserable shock.” He added that the replacement of the gates would have to start from scratch with our father’s original designs and drawings.

The Arboretum Foundation, headed by Jane Stonecipher, sprang into action, communicating with the younger sculptor Tsutakawa, the Seattle Office of Arts and Culture, 4Culture and its own supportive board members. Over a one-year period, the foundation raised more than $150,000 from private and public sources to replace the gates, including reconstruction by Gerard Tsutakawa. One bright spot is that the Memorial Gates likely will be installed in a site more secure and visible to visitors, behind the north entry locked gates. The reinstallation and a community celebration will be later this year, concluding another chapter in my father’s long and celebrated career.

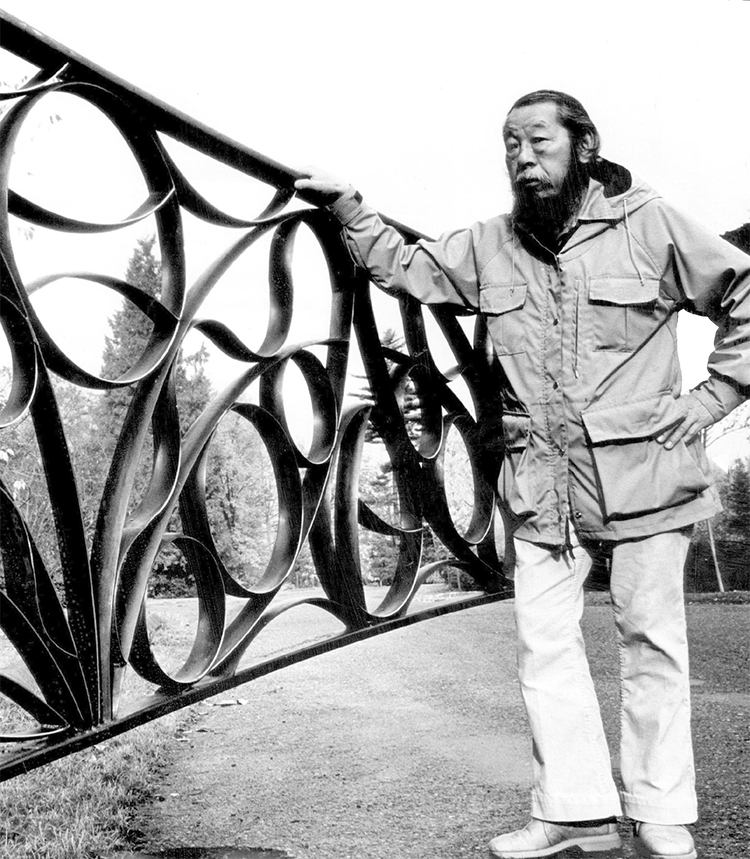

George Tsutakawa shows off one of the “Memorial Gates,” which were commissioned in 1971 by the UW and the Arboretum Foundation to recognize those who built and cared for the Washington Park Arboretum.

George Tsutakawa was the second son of Shozo Tsutakawa, a prosperous businessman who came to Seattle in 1904 to develop an import-export business. George was born on Federal Avenue on Capitol Hill and attended public school there until age 7, when his father moved the family to Japan. He attended school for 10 years in Okayama and Fukuyama. But he was an uninterested academic student, preferring to discover Japanese traditional arts with his two sets of grandparents. Because his father wanted him to continue in the family metal-import business, the two had a falling out. At 16, cognizant of Japan’s growing militarism, George studied Japanese carpentry, then came back to Seattle and never saw his father again.

But he did help his two uncles with a Seattle branch of the family business. He managed and lived behind their produce stand at the corner of Rainier Avenue and Jackson Street. George attended Broadway High School (now Seattle Central College) and studied with excellent art teachers there. At school, he met other emerging Northwest artists such as Morris Graves and Fay Chong.

George enrolled at the UW to continue his art education, receiving his BFA degree in 1937. Due to his obligations to his uncles’ produce market, he didn’t have a lot of time to spend on campus, and what he did have was spent in the art school studios.

His early artwork included linoleum block prints inspired by his experience working in Alaska canneries, and modernist paintings, wood sculptures, lamps and collapsible furniture. George was an active artist, exhibiting in many local and national exhibitions. He took part in the Puyallup Fair Art Exhibit and the International Art Exhibit, held in the Chinatown-International District, with his artist friends such as James Washington Jr., Val Laigo, and Andrew Chin.

During World War II, George was drafted into the U.S. Army. He reached the rank of sergeant and was assigned to teach Japanese language in the Military Intelligence School in Minneapolis. As a Kibei Nisei, born in the U.S. but raised in Japan before returning to Seattle, he was completely bilingual.

Tsutakawa looks over a maquette of the 1971 “Seven Flowers” fountain, which he designed for a site in downtown Bellevue.

He sometimes traveled by train to visit his relatives, specifically his sister and her Moriguchi family, who were incarcerated at the Tule Lake concentration camp in far northern California. He drew upon his understanding of the imprisonment in 1983 when the Japanese American Citizens League asked him to create a sculpture for the Puyallup Fairgrounds in honor of the 8,000 Seattleites of Japanese descent who were detained there for five months before being incarcerated at the Minidoka Camp in Idaho. His design, called “Harmony,” is a column with the figures of a father, mother and children reaching toward each other.

While visiting Tule Lake, George was introduced to Ayame Iwasa, a notable student of Japanese traditional dance who regularly performed on the stage in camp. Ayame, my mother, was also Kibei Nisei, second-generation Japanese American, born in Hollywood in 1924. She too had been sent to Japan and raised in the Okayama area before returning to live in Sacramento. The couple became engaged through an arranged marriage.

After the war, Ayame came to Seattle and the couple married in 1947, living in a tiny house in the alley near 12th Avenue and Alder Street. George enrolled in graduate school under the GI Bill and completed his MFA degree in sculpture from the UW in 1950. He studied with the famed Ukrainian-born sculptor Alexander Archipenko, one of the first Cubist sculptors, when he was a visiting faculty member.

George started his academic career teaching Japanese in the UW’s Far Eastern Studies Department. Then he taught design in the School of Architecture and painting and sculpture in the School of Art. He served on the faculty of the UW for more than 37 years. He was a popular and positive teacher who imparted his love for art to thousands of students.

George’s friendship with the noted Korean American photographer Johsel Namkung led to his discovery of the concept of obos. Johsel introduced George to a book by Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, “Beyond the High Himalayas,” written in 1952. The concept of obos involves the stacking of rocks by pilgrims on high Himalayan passes as a prayer for safe passage. George was taken by this concept and felt it connected humans from the earth to the heavens, as in Shinto rituals. He adopted the idea of stacked shapes in his sculptures and fountains. And he would witness the obos himself when he trekked in Nepal up to 13,000 feet at age 67.

While most famous for his bronze fountains, Tsutakawa explored a variety of media and subjects. his 1950 watercolor, “Beach Images,” is part of the Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science and Engineering art collection.

The Seattle Public Library fountain, his first fountain sculpture, was based on the concept of obos. Titled “Fountain of Wisdom,” it was first sited on the 5th Avenue side of the new library designed by the architectural firm of NBBJ in 1960. Due to his teaching career at the UW, he was well known by the rising young architects of the time. Thus, he was commissioned to install his fountains in many new buildings, parks and shopping malls throughout the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s.

George’s professional art career spanned 60 years. At first, he used oil paints to explore abstract themes. Later, at the urging of the internationally recognized artist Mark Tobey, he began to explore his cultural roots and use sumi paint to depict landscapes and sea life. My parents welcomed Tobey and other Seattle artists such as Paul Horiuchi to come paint with sumi ink together at art salons in our home.

In 1955, George and Ayame had settled into a large, historic home overlooking the I-90 bridge in the Mount Baker neighborhood of Seattle. The metal-fabrication shop and wood sculpture studio took up the garage and basement. Today the home houses many of George’s early and later artwork.

The couple had four children, all of whom went on to work in the arts as artists, musicians, teachers and writers. After many years apprenticing under our father, then managing their major sculpture projects, Gerard became a metal and wood sculptor. Younger brother Deems became a jazz musician, youngest brother Marcus, ’78, ’83, became a symphony orchestra conductor and I, Mayumi, am an arts writer. Nine members of our extended family earned degrees from or otherwise attended the UW.

While our family traveled through the Pacific Northwest and the U.S., the most significant of George’s travels included the sites of ancient civilizations such as the Mayan ruins at Chichén Itzá in Mexico, the pyramids in Egypt, and the ancient palaces of Angkor Wat in Cambodia. As a humanist, he was not religious but believed in the deep value of humanity and its cultural achievements.

Ayame was a talented and culturally refined hostess and arts advocate as well as a mother of four and grandmother of seven. She was George’s primary business manager, especially as he took on larger and more complicated international projects. And she welcomed many notable visitors at our home, including legendary Japanese ceramicist Shoji Hamada, wood furniture designer George Nakashima and visionary sculptor Isamu Noguchi. She passed away in 2017 at age 93.

Courtesy of the Arboretum Foundation.

George created more than 75 fountains and sculptures, many of which are still on view in public spaces in North America and Japan. He also taught art at the UW for more than 30 years and influenced generations of students. In 1984, his career was recognized as a University of Washington Alumnus Summa Laude Dignatus, the highest honor bestowed upon an alumnus by the UW and the UW Alumni Association. He was given honorary doctorate degrees from Whitman College and Seattle University and received notable awards from the emperor of Japan and from the National Japanese American Citizen’s League. The Seattle Art Museum has 21 of his works, the earliest dating to 1931, in its permanent collection.

My father died in his Seattle home in 1997 at age 87. Now, thanks to the work of donors, volunteers and the Tsutakawa family, the gates he designed, a beloved landmark to thousands of visitors each year, will soon return to their home at the arboretum.

Pictured at top: George Tsutakawa polishes the bronze gates he designed for the Washington Park Arboretum.