Stories to tell Stories to tell Stories to tell

The 4-year-old Sea Mar Museum is the first in the Pacific Northwest to represent Chicano and Latino culture

By Hannelore Sudermann | Photos by April Hong | Viewpoint Magazine

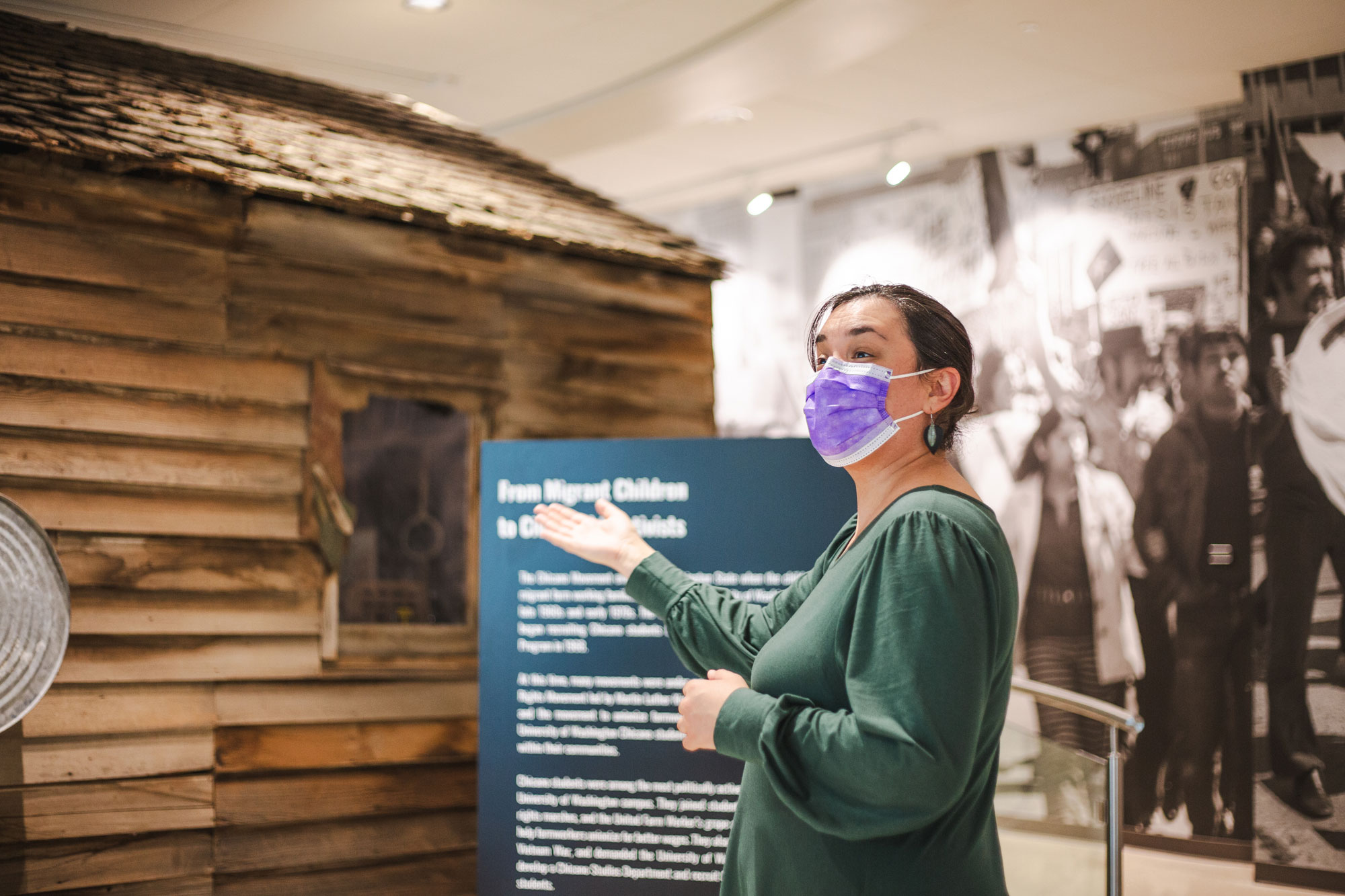

Just inside the door of the Sea Mar Museum of Chicano/a/Latino/a Culture stand two authentic, intact farmworker cabins. The one-room wooden shacks were painstakingly relocated from a farm in Eastern Washington, where they once housed families of workers who traveled the West for seasonal employment in the fields and orchards of the Columbia Basin. Their presence is testimony to the rugged realities of the Mexican and Mexican American families who sought opportunity in Washington.

This exhibit, representing the first surge of Chicanos and Latinos moving to Washington around the time of World War II opens the experience of the 4-year-old museum in South Seattle. One of the newest culturally specific museums in the region, it first welcomed visitors in fall 2019, just months before the COVID-19 pandemic. But its founders have been dreaming of this project for decades.

In the late 1960s, nearly all of Washington’s Hispanic residents lived east of the Cascades. Of them, a few—often the children or grandchildren of the immigrant families—came to Seattle to study at the University of Washington, where they formed a community dedicated to social change. Inspired by the farmworker movement in California and activism around civil rights and the Vietnam War, they organized, became student leaders and expanded their reach into the greater Seattle community. On campus, they persuaded their classmates to boycott the residence halls and the HUB to stop them from selling non-union grapes as part of a grape boycott. They joined forces with the Black Student Union, Native American students and Asian American students to push for more faculty of color and the expansion of class offerings to include in Chicano history and literature.

- Teofila Cruz-Uribe, ’17, ’18, uses her UW graduate degrees in international studies and museology in her role as the museum’s director.

- One section of the Sea Mar Museum highlights student activism on campus at the UW through a Latino lens.

- Professor emeritus Erasmo Gamboa serves as an advisor to the Sea Mar Museum.

Click or tap photos to enlarge and read captions.

Those early students—many of whom graduated to become teachers, lawyers and business leaders—created the foundation for a vibrant Hispanic and Latino community in the Puget Sound region, says Professor Emeritus Erasmo Gamboa, ’70, ’73, ’84. Gamboa was one of them. His parents, Mexican immigrants, had moved the family to Eastern Washington, and he grew up in Yakima Valley. He has memories of living in a farmworker cabin as a child. He was one of the first students of color recruited to the UW in 1968 in the precursor to the Educational Opportunity Program and became a historian of the West, with a focus on the Latino experience. His fellow students included Rogelio Riojas, ’73, ’75, ’77, a UW Regent and a founder and CEO of Sea Mar Community Health Centers; Norma Zavala, ’80, ’02, ’07, a Seattle-area education leader who serves on the museum’s board; and architecture alumnus, Jose Bazán, ’78, ’80, who designed the museum space and advised on how to develop the exhibits, which include a rich assortment of artifacts and art. “We didn’t start with a thousand artifacts, but we had the idea, the commitment,” Gamboa says. They reached out to families they knew would have memorabilia. The encouraged a Yakima-area farm family to donate the cabins. They visited museums around the country, then decided not to pretty-up the artifacts. “We want to tell our story with the rust, with the blemishes,” Gamboa says. “The cabins’ thin walls and knob and tube wiring within the reach of children helps tell the story.”

Many things set this museum apart, including that it is the first in the Pacific Northwest to represent Chicano and Latino culture, but it may be unique in the nation with its ties to a community health center. In fact, it shares a building with Sea Mar’s adolescent medical clinic, as well as the organization’s two Spanish-language radio stations. Sea Mar, a health and human services non-profit, was founded by UW alumni in 1978 to serve the Latino community.

The dream was always to have a museum dedicated to sharing the stories of the Latino/a experience in Washington, says Teofila Cruz-Uribe, ’17, ’18, who uses her UW graduate degrees in international studies and museology in her role as the museum’s director. “There is a gap in the public record where oftentimes the presence of Latinos in this state is overlooked. Sea Mar was founded to serve the underserved community, and the mission has expanded to include being a resource for community, history and identity.”

Behind the diorama of life on an Eastern Washington farm, massive photographic murals of protest and activism in Washington in the 1960s and ’70s lead the way to the next gallery. Gamboa points out and names people he recognizes. Further back, the museum opens to a large room filled with items and photographs that break into vignettes. One section tells the story of labor, with ephemera from orchards and hop farms. Others focus on community, rife with instruments, posters and sports equipment. A special section focuses on military service. Another highlights University of Washington and student activism. All built around the Latino experience.

The museum is by no means complete, Gamboa says. The plans are to push through the back wall into an existing space now filled with offices. “We continue to collect and continue to flesh out our vision of the story our museum should tell,” he says.