On the first day of the class Native Art of the Northwest Coast, the term “Siʔaɫ” pops up on the Zoom screen. It’s the Lushootseed word for “Seattle,” the Duwamish-Suquamish chief the city was named after. Professor Kathryn Bunn-Marcuse asks the 155-person class to unmute their microphones, all at once, so that she can teach them how to pronounce it.

“To say this barred ‘L’ at the end, you put the tip of your tongue on the roof of your mouth, behind your teeth, and you blow air out the side,” she says. “And since we’re not in class, you won’t be spitting on anyone.” The apostrophe in the middle of the word is a glottal stop, she adds, like when you briefly pause in the middle of the phrase “uh-oh.” A cacophony of voices ping-pongs around the Zoom room as the students try it out:

See—pause—ahlsh.

See—pause—ahlsh.

See—pause—ahlsh.

Bunn-Marcuse smiles in acknowledgment of the chaos, and promptly asks everyone to mute themselves. The vocal lesson has another purpose: It’s a collective land acknowledgment at the start of the quarter. “That is the name of our city,” Bunn-Marcuse says, telling the students that throughout the quarter, they will take turns sharing a longer land acknowledgment each time the group convenes.

The fact that the class is being taught remotely, with students from across the state and the nation, actually contributes in a way. On a virtual map from native-land.ca, Bunn-Marcuse asks students to plot where they currently are, and the map converts it to Native terms—most of which are still recognizable to us. Today’s students are in land that first belonged to the following tribes: Seattle, Snohomish, Snoqualmie, Puyallup, Tulalip, Yakima, Spokane, Nooksack, Stillaguamish, Butte, Okanagan, Massachusett, and Cherokee. This exercise lets the students think about how the class is inhabiting or occupying a wide swath of Indigenous land because they’re not at UW.

The class has a particular weight this quarter because of the passing of the legendary Bill Holm in December 2020. Holm, a leading scholar of Native art and art history, mentored Bunn-Marcuse, ’98, ’07, and was like a grandfather to her children. Even though Holm is no longer with us, students at the UW continue to learn through the people who learned from him, teaching the classes he helped shape. Holm taught a three-quarter sequence of Native art to UW students in the 1970s, inviting anyone in the community to sit in on the class. The auditors included Indigenous artists like Haa’yuups Ron Hamilton and Joe David. People crowded in and sat in the aisles in Kane Hall.

That’s because Holm knew his stuff. As an outsider to Native arts and culture, he had immersed himself in the Burke Museum beginning as a teenager in the 1940s, learning from director Erna Gunther before traveling the region to meet Native artists and learn about their craft. “They were really interested in talking to him, because he was really interested in talking to them,” says Bunn-Marcuse. “His strength was that he was incredibly humble and generous.”

Holm became an encyclopedia of archival history and a bridge between cultures, mastering the contents of museum collections and traveling the world to give what he had learned to the next generation. In 1965, he published the book “Northwest Coast Indian Art: An Analysis of Form,” which became a Rosetta Stone for generations of Native artists looking to converse with their ancestors. His personal collection of 30,000 images of Northwest art was the stuff of legend: Young artists and scholars reached out by letters, then emails, asking him for copies of images or for advice about technical instruction or cultural history.

Holm had learned techniques from reading anthropological texts, talking with older Indigenous artists or trying the skills with his bare hands. He made beadwork, textiles, cedar canoes and totem poles. “I’m at my heart a hobbyist,” he once told UW Magazine. “I started with Indian design because I was thrilled by it.”

Bunn-Marcuse grew up in Honolulu but came to the mainland many summers to attend a camp in the San Juan Islands, where she met Holm and his family. “I didn’t know when I was young that Bill was a scholar of Native art,” she recalls. “I just knew he had a lot of interesting friends.” She graduated from the University of Washington before becoming a professor in the School of Art + Art History + Design, studying under Dr. Robin K. Wright. “There aren’t that many places where you can get a Ph.D. in Native art from someone who has a Ph.D. in Native art, so this is where I ended up,” Bunn-Marcuse says.

Of the 155 students in the class, only one is an art history major (another is an American Indian Studies major). The rest span the spectrum, from biology to political science, and 80 of them are undecided. Bunn-Marcuse hopes to recruit a few to art history. She wants them to know that art history isn’t just about looking at pretty pictures on a projector. It’s about political history and modern politics, social structures and economics, cultural situations and cultural dynamics. There is, then, a momentousness to art history, especially in the context of Native populations whose land, resources and cultures are often under threat.

The course starts with the Tlingit tribes in Southeast Alaska. We see how the body is used as a “cultural system,” with status, rank and identity indicated by woven robes, clan hats, beaded collars, leather aprons and headdresses. Bunn-Marcuse, who is not Native, makes a point to bring in Native artists to discuss their culture and artwork. This quarter, Tlingit weaver Lily Hope speaks to the class for nearly an hour, sharing a behind-the-scenes look at her loom, her materials and her mindset. This process, known as Chilkat weaving, can take hundreds of hours to produce a single blanket, which are reserved for special ceremonies.

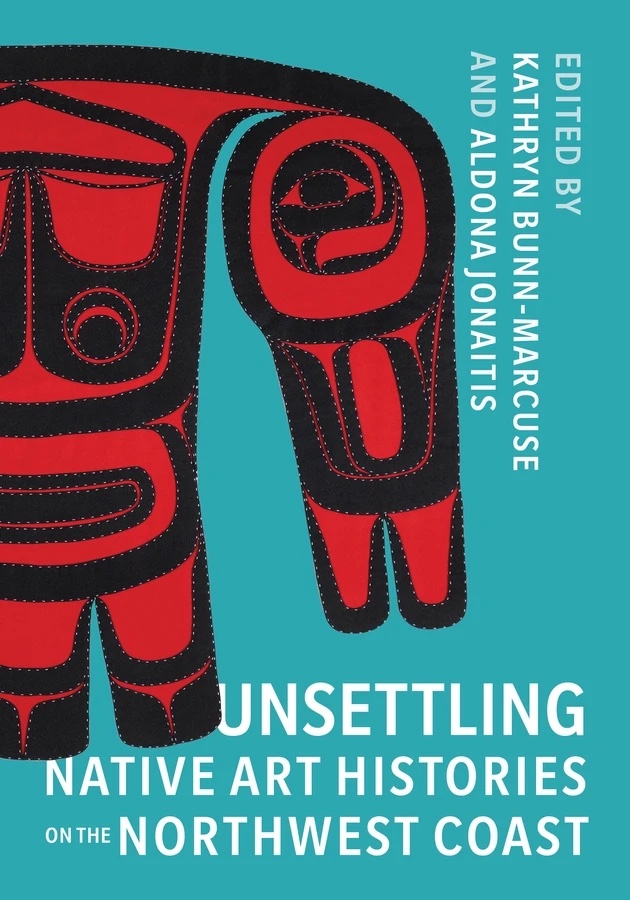

The distinct style of formline design can be seen on a Tlingit robe by artist Alison Bremner, which is featured on the cover of Bunn-Marcuse’s new book, “Unsettling Native Art: Histories on the Northwest Coast” (pictured above). Bill Holm coined the term formline to describe the system of u-shapes, ovoids, and s-shapes commonly employed by Northern Northwest tribes. Bunn-Marcuse explains: “You can recognize this black-red-blue painted design system because it’s governed by a set of guidelines that artists have followed for a long time and continue to follow. But within that system, there’s a huge amount of creativity and dynamic change.”

Bremner’s dance robe is titled “Raven’s Cloak” and was made from wool and beads in 2014. She is also a painter and woodcarver, and she is believed to be the first Tlingit woman to carve and raise a totem pole.

Next, students look at Haida art, which originates off the coast of current British Columbia and is defined by formline design. They learn about work by modern woodcarvers and sculptors like Bill Reid and watch the film Edge of the Knife, the first Haida-language film, with a special visit from the co-directer Gwaai Edenshaw.

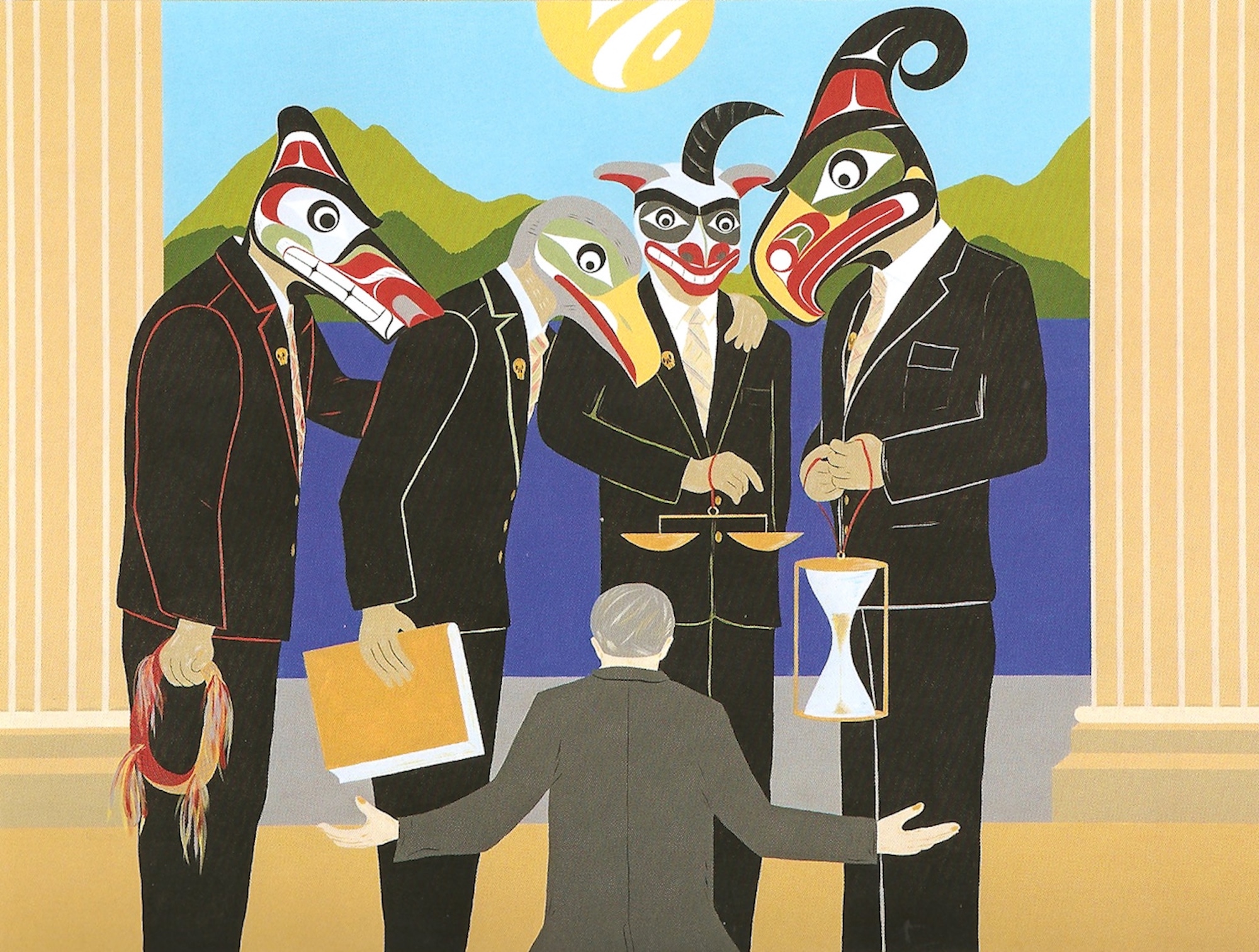

Elsewhere in British Columbia, the students learn about the art and ceremonies of the Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw peoples, which includes virtual visits by multimedia artist Rande Cook and artist Carey Newman. Next, they study the masterful and at times monumental carving of Tsimshian artist David Robert Boxley, who creates masks, drums and totem poles. Boxley also paints on paper, leather and hide.

Making their way down to Washington state, the students look at traditional and contemporary artwork by Coast Salish peoples, such as the Puyallup and Tulalip, whose work doesn’t use the northern formline design. Instead, Salish art is characterized by how carvers and painters use negative space—the unpainted or cut-out areas—to define the form or suggest movement. Shaun Peterson (Qwalsius), a Puyallup artist and scholar, explains this visual design system in this video.

What’s more, Salish traditions often required keeping artwork in private. According to Peterson: “For generations it was believed that if one publicly displayed objects that depicted specific animals, they might be regarded as beings associated with one’s spirituality, thereby striking against a cultural value to be humble.” While totem poles were not part of Salish practices, in the early 20th century, Peterson notes, Salish artists shifted toward carving story poles as a way to honor and maintain “the way of life, stories, and sculptural style of the people were at risk of disappearing,” thus emphasizing the importance of the contemporary artist in keeping culture alive.

Students finish the quarter along the largest river in Washington, the Columbia, which carves its way through the middle of the state before turning westward and creating the border with Oregon. The art often takes the form of material items such as bowls, clubs or baskets, and can be made of wood, stone, bone or any number of natural materials.

It’s no surprise that many of the Lower Columbia River people are known as excellent canoe builders. Chinook artist Tony (naschio) Johnson visits the class to talk about his magnificent new project outside of the Burke Museum: an assembly of 13 bronze canoe paddles, standing upright in a distinguished formation (pictured in the next section).

It helps that the class is land-based and taught geographically, taking students on a virtual journey from one area to the next—and not chronologically, from past to present, like a typical art history survey course. The latter format might reinforce stereotypes that Native culture is of the past, or “vanished,” rather than present and thriving, especially in art.

“So, we sit with the dissonance of all that we face.

And borrow the courage and mirror the grace.

We are braced by the generous spirit that shares. And we talk and we trust. We cry and we care.

Woven amidst the tears we let go, there is love, there is laughter, there is friendship and hope.”

Excerpt from the poem "Bearing Witness" by Carey Newman (Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw), which the artist performed for the students in class

For many students, this framework will shake up their understanding of American history. The history of the U.S. has often been about getting rid of Native people, and American history often fails to include Native stories, save for broad strokes about conflict or removal. While Seattleites can walk the streets and see totem poles, some students may come from parts of the U.S. where Native culture is less visible.

“I think a lot of people have outdated, overly romantic or anthropologically driven ideas of who Indigenous people are,” Bunn-Marcuse says, referencing age-old archetypes such as the “vanishing Indian,” which was used to justify the American government’s westward expansion and the removal of Native people. By bringing in contemporary artists and looking at contemporary art, Bunn-Marcuse hopes to confront these lingering and at times pervasive stereotypes.

Bunn-Marcuse’s new book opens with a common quote about Indigenous art: “We have no word for art in our language.” Bunn-Marcuse rejects this implication that there is no Indigenous language for art while explaining that the Euro/American conception of “Art”—as a word and as an idea—has often “been imposed by outsiders and applied in a manner that erases cultural function, kinship connections, or the spiritual power of cultural creation or belongings.” In the context of this class, and in the context of museums and Western culture broadly, the creations of Native people that we label as “art” may be functional, spiritual, ceremonial, performative, or relational. In other words, the pieces aren’t simply made to be framed on walls or sold to the highest bidder; they fit into specific societies, cultures and hierarchies, and they have to be understood and appreciated that way.

“Relationships are often at the heart of Indigenous art,” Bunn-Marcuse says. That can be between people and land, people and non-human beings, and people and larger regions. A class like this is not just about art-making and the importance of art, but it’s about teaching people to engage with an entirely different cultural outlook. “Appreciation only takes you so far. I want them to move into places of fascination and wonder, and ethical considerations of their own position,” Bunn-Marcuse says. In other words, she wants them to see contemporary politics and activism through the lens of art.

Lineage Robe © Lily Hope

Chilkat weaving is woven formline design. Weaving is usually geometric, but this has curvilinear shapes. It can take up to two years to make a robe. See more.

“Guests of the Great River” by Tony A. (naschio) Johnson and Adam McIsaac. Photo: Washington State Arts Commission

Chinook art from the Columbia river has been under-appreciated and is coming back into practice. This sculpture, “Guests of the Great River,” is a series of bronze canoe paddles outside of the Burke Museum. See more.

“Whale Rider Drum” by David Robert Boxley. Deer Hide, Acrylic, Leather, Wooden Beater. Stonington Gallery.

One of the great contemporary artists of the northern formline design, Boxley understands the complexities and possibilities inside of that system. See more.

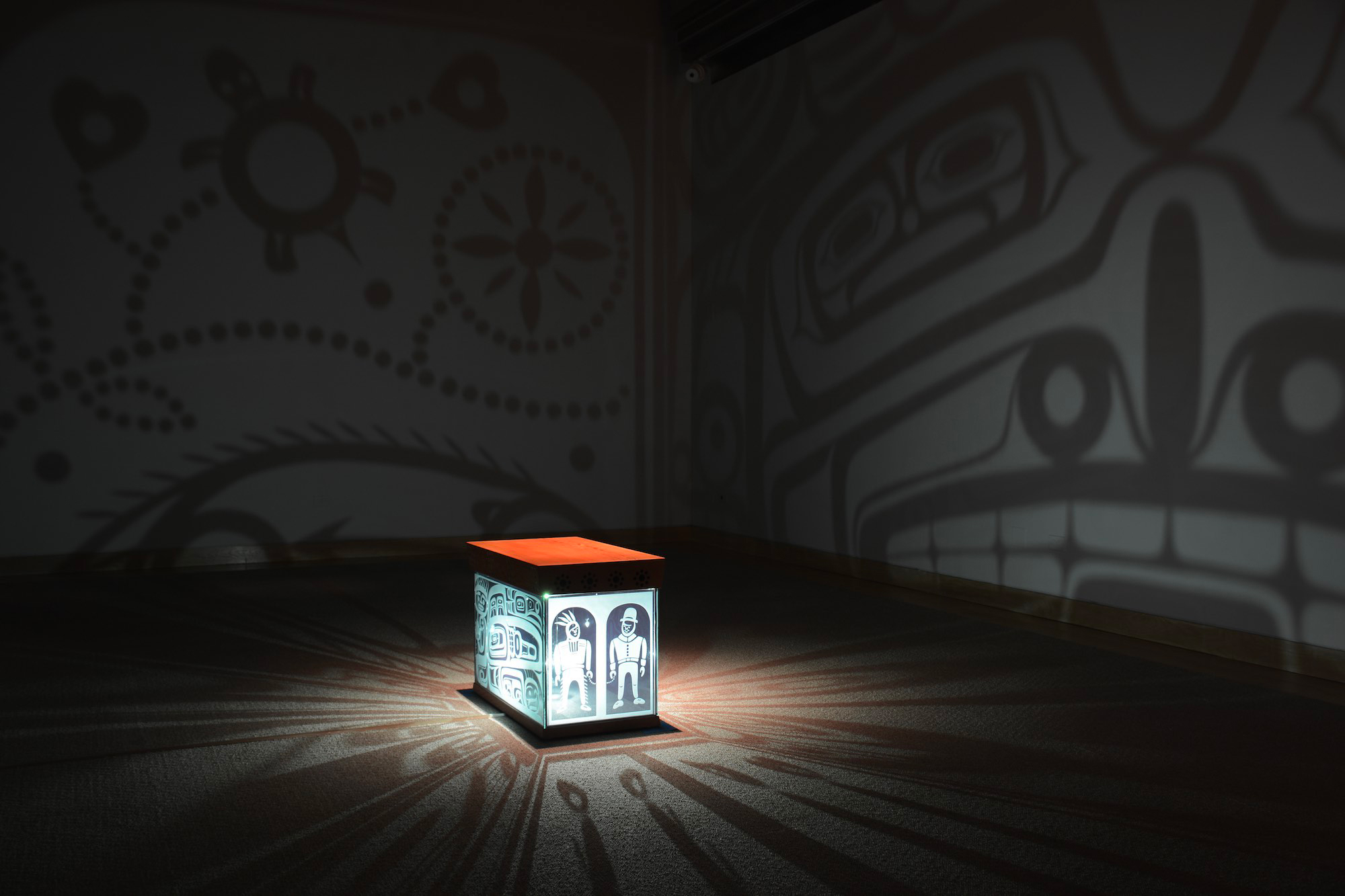

“The Harbinger of Catastrophe” (detail) by Marianne Nicolson, 2017. Glass, wood, halogen-bulb mechanism. Collection of the artist. Joshua Voda/NMAI, Smithsonian

Nicolson makes place-based work often consisting of large, public pieces of art. She makes us think about how artworks let us discuss understandings of place, politics and history.

If you live in the Seattle area, you don’t have to go far—or even indoors—to find Native art. There are totem poles around Pioneer Square, downtown manhole covers by Nathan Jackson, tree grates by Susan Point, a welcome figure by Marvin Oliver in the Salmon Bay Natural Area, and a team of all-women Salish artists bringing art to the waterfront.

The Internet is often the closest location to learn more about Native art. Here are some videos that students watch in Bunn-Marcuse’s class. Follow along with your own syllabus at home:

Assistant Professor Kathryn Bunn-Marcuse is the curator of Northwest Native art and director of the Bill Holm Center for the Study of Northwest Native Art at the Burke Museum. In her role as curator, she collaborates with First Nations communities and artists to activate the Burke Museum’s holdings in ways that are responsive to cultural revitalization efforts. She earned her M.A. (1998) and Ph.D. (2007) from the University of Washington.