If things had worked out as Art Wolfe, '75, planned, chances are we would never have gotten to see the works of one of the most renowned nature photographers in the world. He would have been spending his time in a high school classroom instead, teaching art.

A double major in painting and art education at the University of Washington, he had pretty much given up on a career in painting after seeing the struggles of his faculty mentors. After all, they weren’t making their livings exclusively as painters; they had day jobs, too.

So Wolfe figured he’d teach art, and continue to paint on the side. But just as his hope to be a painter went by the wayside, so did his teaching career. A double levy failure and resulting budget cuts made teaching jobs scarce in Seattle. Then a teachers’ strike forced him to consider crossing picket lines as a substitute teacher. If that weren’t enough, there was his one year in the classroom:

“I hated it,” he says. “I didn’t have the patience to put up with teaching and the kids. I would have slugged someone. I only looked at teaching to put bread on my table. I really wanted to be a painter.”

So he quit teaching and started spending more time on photography, a hobby he picked up in high school, and shot photos of his favorite subject—the outdoors.

Never one to lack confidence, Wolfe started selling his photos at street fairs. Then he showed them to his mountain climbing instructor, who just happened to be the head of The Mountaineers Books. A year later, he was working on his first book, Indian Baskets of the Northwest Coast. Then came an $11,000 government contract to photograph wildlife in the U.S.

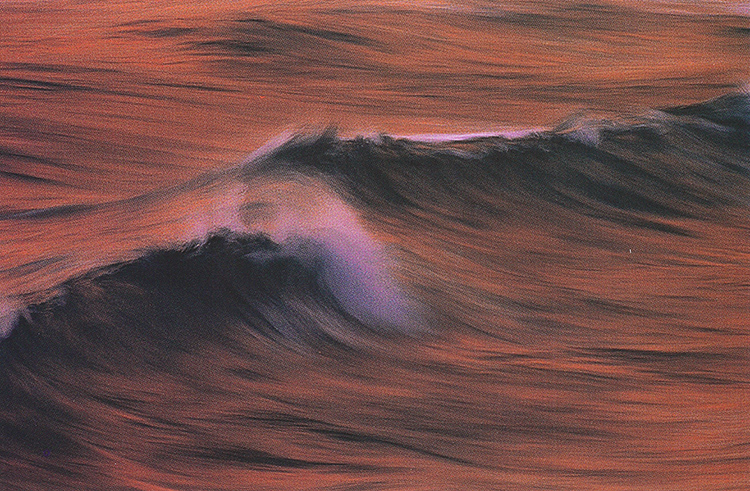

Wolfe uses long exposures to let this wave off the coast of the big island of Hawaii paint itself on film.

Then came magazine stories, magazine covers, books, calendars, museum exhibitions and a 25-year career in which Art Wolfe established himself as one of the most renowned nature photographers of our time. Now living in a gorgeous, split-level West Seattle home with a killer view of Puget Sound—a half-mile from where he grew up and a mile from where he was born—Wolfe employs a full-time staff of 14 that runs his business while he is globetrotting, and that he considers his extended family.

“I never had a plan,” says Wolfe, 47, who’s single, and is being interviewed at home in between overseas trips to shoot photos for a new series of books. “I just developed a viable occupation. I made a lucky connection in the beginning, and it was a new profession. There weren’t a lot of fine-art nature photographers then, mostly naturalists who took photos. I just took the opportunity at the right time, started selling photographs and never looked back.”

While his photographs are stunning, his resounding success is equally attributable to his ability to sell himself and his ideas.

“His energy level is amazing,” says Barbara Sleeper, ’72, ’91, a Seattle science writer who has worked on three books with Wolfe. “He has so many ideas and sees so many possibilities, he makes you feel exhausted. Very inspiring, but creatively exhausting.”

Juvenile leaves of an aroid in Panama.

It’s that enthusiasm and devotion to his craft—”I don’t take a day off,” he says matter-of-factly-that has made him what he is today. On the road nine months a year, he travels to remote regions of the world, shoots 2,000 rolls of film a year and is booked a year and a half in advance. “I get addicted to travel, addicted to anticipating my shots,” he says. “I become a junkie with film.”

His nature was evident while he was a student at the UW. A graduate of Sealth High School, he spent a year at Highline Community College before transferring to the UW. A talented and prolific watercolor painter, he produced abstract, outdoors-oriented paintings, but was probably more well-known for donating a used refrigerator to the painting students’ studio—and his strong personality.

“He was very memorable,” says Hazel Koenig, one of his art education instructors. “He was very aggressive in class and questioned things all the time. He had quite a personality.” Wolfe’s view: “I am sure the teachers hated me. I was a devil in class. I was always questioning authority. I’m sure they wanted to kill me.”

Yet he got along well with his instructors and soaked up everything he could. In was in art school that Wolfe—whose first commissioned painting for a junior high school teacher netted him $22—learned the finer points of design, abstraction and pattern.

For the past two and a half decades, Wolfe’s photographs have been recognized worldwide for their mastery of color, composition, perspective and expressions on wild animals’ faces. “His eye contact with animals is phenomenal,” says Sleeper, “He talks to the animals, and he has such a presence. He seems to captivate them and look into their soul. You can feel the connection.”

His approach to photography is based both on his training in the arts and his love of the environment. As a child, he spent many weekends camping with his family in the Cascades along Nason Creek, exploring the Oregon coast or taking day trips to Mount Rainier. While a college student, he spent his weekends hiking the Washington coast, his summers climbing peaks in the Cascades or Olympics.

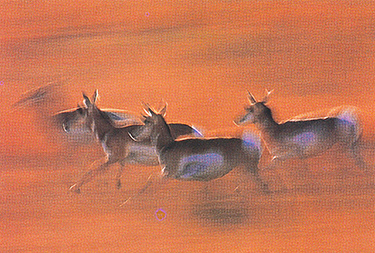

Going back to his roots as a painter, Wolfe likes to create impressionistic images such as this one of pronghorns in Wyoming.

“Forest, mountain and ocean were the themes that defined my travel experiences well into my young adulthood,” he says. “For the most part, they form what I am today.

“I love the process of creating a photo that may be a very intimate experience for me,” he goes on. “If I’m successful, that photo could conceivably be seen by millions of people. I love the communication factor of that process.”

His art background heavily influences everything he does, from his photography to the way he decorates his home. “Everything is cloaked with a strong sense of composition, a sense of light and direction from light, a sensitivity to textures and shapes and line, which I learned from painting,” he says. “All the elements of design run through my photos. I think it’s given me an advantage.”

Another advantage is his ongoing desire to seek out new approaches to what he does. After spending most of his early career shooting the sharpest, most well-defined photographs of wildlife possible, he switched gears in the early 1990s, using long exposures and panning his camera to create impressionistic imagery.

His 1997 book, Rhythms of the Wild, marked a new development in his work-capturing movement in a far more painterly fashion than anything he had done before. ” I came to photography as a painter with a fine-arts background,” he says. “The pictures in this book reflect those origins as I spiral ahead with my ongoing work in photography.” Using a tripod for long exposures of at least one or two seconds, he turns running zebras into a swirling pattern of black and white lines, a wave off the Hawaiian coast into an image that you would swear came off the end of a paintbrush.

This digital illustration of a pack of zebras is Wolfe’s most popular and controversial image.

Ironically the same desire to innovate that helped make him famous also got him into hot water in the photographic community with the release of one of his most famous books, Migrations. In that book-which pays homage to the mesmerizing pattern works of M.C. Escher, one of the biggest influences on Wolfe’s career-Wolfe digitally altered about a third of the book’s images, including the cover shot of a herd of zebras which has become by far and away his most popular and biggest-selling image. It was 1994 and digital imaging was an emerging technology. Wolfe-who cloned individual zebras for the famous zebra herd shot -employed the computer to correct an image of a mass of animals where invariably one animal would be wandering in the wrong direction, thus disrupting the pattern he was trying to achieve. (Digitally altering images actually began in the 1980s.)

“In Migrations, I embraced the technology that was available to me,” he says, “and I took the art of the camera to its limits. This was not a moral issue. It was just that in the beginning, we were naive. We didn’t use identification. That is the sole issue. Photography has never been an accurate recording of what is out there. For years photographers have manipulated images by using different lenses, filters, films and in the darkroom.”

Critics caught Wolfe by surprise by crying foul, saying digital imaging had no place in a nature book. Wolfe argued that the book was an art book-he says so in the book’s foreword-and that the controversy was blown out of proportion because of one simple fact: he didn’t identify the images he altered.

Galen Rowell, a contemporary of Wolfe’s as an accomplished nature photographer, was among those who criticized Migrations. In a five-page letter to Wolfe, Rowell alternately scolded his friend and professed admiration for his work. His bottom line, though: “Don’t do anything you wouldn’t feel comfortable having fully revealed in a caption.”

A slow shutter speed allows Wolfe to meet the challenge of illustrating the wind blowing through this stand of Bluegum Eucalyptus trees in California.

Others, such as Gary Braasch, chair of the North American Nature Photography Association, were steadfast: “Nature photography is one of the last bastions of pictures most people accept as real. Those who lie about the reality of their photos are taking advantage of everyone else and undercutting the basis of all our success.”

True to form, when the debate was white hot, Wolfe always stood front and center to take on any naysayers, as he did in photography workshops around the nation, where he debated against naturalists and other wildlife photographers.

Wolfe had hoped to use this granite arch in the Alabama Hills of the Eastern Sierra in California to frame the dramatic vista of Mount Whitney, but a passing cloud formation intervened, creating a more abstract vision.

Today, the debate continues— Atlantic Monthly recently ran a 20-page article on the ethics of digitally altering photos-but Wolfe has put it behind him. “I hated the controversy but was very glad people noticed,” Wolfe says. “I wanted to capture spirits and uplift, and I won’t apologize for that.” Ever since Migrations, he has identified every image in a book that has been digitally altered.

He continues to embrace any and all new technology-“If you don’t, you will be left behind,” he says-and continues to produce some of the most dazzling imagery anywhere.

His current work can be seen in three books released this fall: Rainforests of the World: Water, Fire, Earth and Air, Pacific Northwest: Land of Light and Water; and Northwest Animal Babies.

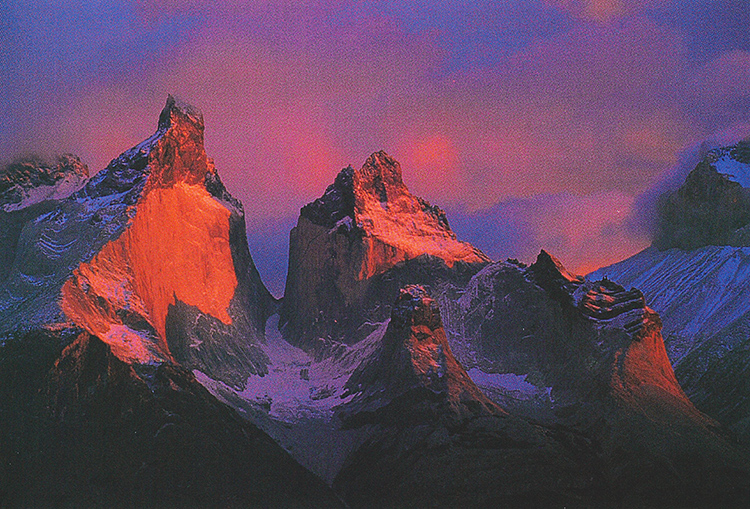

Pre-sunrise light paints a dazzling picture in Patagonia’s Torres Del Paine National Park in Chile.

The book on the Northwest was especially close to his heart. “Although I love the Antarctic and the plains of Africa, I have to admit my favorite places lie in the Pacific Northwest,” he says. “This is precisely why I have lived here all my life. With all the traveling that I do, it is very grounding to live in the same place where I was born, reared and began my life of natural exploration.

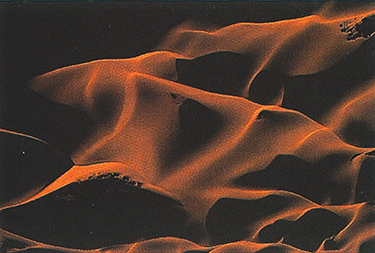

Taking to the air, Wolfe captures the abstract patterns of sand dunes in Death Valley, California.

“I have also watched over the years as other people have discovered what the Northwest is all about. It is no longer a secret, and there are many forces that undermine the integrity of its diverse environments. Without some forward-thinking politicians who can guide strong environmental legislation, I fear that every acre of unprotected forest, every mile of unprotected riverside and lakeshore, will eventually be covered with homes and business.”

Wolfe puts his money where his mouth is. He produces a multi-media program to raise money for various charities, including the Northwest AIDS Foundation, the E. Donnall Thomas Guild of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, the Woodland Park Zoo, the Seattle Children’s Home and the Alaska Coalition of Washington. His office also has an internship program for college students, some of whom come from the UW.

He is not one to stand still. Busy developing art galleries for new REI stores in Denver and Tokyo, Wolfe-known locally for his dazzling gallery at the downtown Seattle REI store-has more books in the works, more traveling to do. His stay in Seattle will be short. The wild is calling.

Sandhill cranes create a wave of flight against a glorious sunrise in New Mexico.

Some recent books by Art Wolfe

Art Wolfe

Rainforests of the World: Water, Fire, Earth and Air. Photos by Art Wolfe, text by Sir Ghillean Prance. Crown Publishers, Inc., New York, 1998. $45

Pacific Northwest: Land of Light and Water. Photos by Art Wolfe, text by Brenda Peterson. Sasquatch Books, Seattle, 1998. $24.95 paperback, $35 hard cover, $64 hard cover collector’s edition, signed, numbered, boxed with poster.

Northwest Animal Babies. Photos by Art Wolfe, text by Andrea Helman. Sasquatch Books, Seattle, 1998. $15.95

Rhythms from the Wild. Photos by Art Wolfe, introduction by Art Davidson. Watson/Guptill-Amphoto Art, 1997. $35

Migrations: Wildlife in Motion. Photos by Art Wolfe, text by Barbara Sleeper. Beyond Words Publishing, Inc., Hillsboro, Ore., 1994. $60

Light on the Land. Photos by Art Wolfe, text by Art Davidson. Beyond Words Publishing Inc., Hillsboro, Ore., 1991. $75