The famous photo of two teenagers hard at work on a Teletype terminal in the late 1960s never fails to make us smile. Paul Allen and Bill Gates, pals from Lakeside School, made their way to the UW campus every chance they could to scavenge time on UW’s computers, writing programs and developing the know-how they would parlay into one of the most innovative and successful companies on Earth: Microsoft.

Back then, they probably had no idea how their passion and drive would revolutionize our lives. It so fitting that today, in the heart of the UW campus, where much of it began, you will find the Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering, housed inside two magnificent buildings: the Paul G. Allen Center and the new Bill & Melinda Gates Center, just across the street from each other. Talk about symbolism!

February’s grand opening of the Gates Center was the capstone of a dream that was many years in the making. The accomplishments of Bill, Melinda, and Paul inspired a community—of state and university officials, friends, colleagues and businesses—to join forces and contribute the resources that completed an extraordinary complex of facilities for computer science education and research.

“This is a wonderful Seattle story,” says Ed Lazowska, the Bill & Melinda Gates chair in the Paul G. Allen School. “When I joined UW, computer science had a dozen faculty members, and Microsoft was a dozen 20-somethings in Albuquerque. Today, the Paul G. Allen School is one of the world’s leading computer science programs, and the Puget Sound region is one of the world’s great technology centers. We’re blessed to belong to a true community—people and organizations that help one another to grow and excel.”

Ah, there’s that word. Community. The UW is famous for lots of things, none more so than the way collaboration and community engagement take place all over the institution. It doesn’t matter if it’s libraries or medicine or computer science or classics. Collaborating to address the big issues of our time is a big reason why the UW has become one of the truly preeminent computer science programs in the nation, competing with the likes of Stanford, MIT, UC Berkeley and Carnegie Mellon for faculty and graduate students, and earning a national reputation for the quality of its undergraduate programs.

Forget the days when business administration or psychology were the top first-choice majors of incoming UW freshmen. Today, it’s computer science—and it isn’t even close. “The long-term trend is clear,” Lazowska told GeekWire recently, “due to the long-term role of computer science in the world. And our region is at the center of much of this.”

And the reason why our region is at the center? The long-term partnership between UW and Seattle’s tech community.

The Paul G. Allen Center, which opened in 2003, was a huge lift to UW’s computer science program, providing the laboratory space that enabled it to complete with the elite tier. But it didn’t take long for those new facilities to max out. In the decade following the opening of the Allen Center, the school added more than a dozen new faculty members and more than tripled its research output.

During the same period, the number of students enrolled in the program increased by 50 percent and legislative leaders announced a plan to double enrollment from that level, responding to dramatic growth in demand from students and employers. Something had to be done.

So a public-private partnership was forged to assemble the $110 million required to construct a second building—a building with additional laboratories, yes, but with its main emphasis on student capacity and the student experience. This partnership included the state Legislature, the University, leading tech companies including Microsoft, Amazon, Zillow, Google and Madrona Venture Group, and more than 500 individuals.

One particular community of donors was a group that became known as the “Friends of Bill and Melinda.” Led by Microsoft President Brad Smith, his wife Kathy Surace-Smith, and Charles and Lisa Simonyi, this group of 13 couples and Microsoft provided the funding to name the building for Bill and Melinda Gates.

They did it as a gesture of friendship and gratitude for a couple who had done so much for the University, the field and the world—and to make sure the UW maintained its position as an international leader in computer science. Unaware of this effort, which was being carried out very quietly, Bill and Melinda stepped in to complete the fundraising for the project.

“This project was a wonderful journey that gave many of us an opportunity to partner together—even competitors,” Brad Smith says of the fundraising campaign. “We at Microsoft had the opportunity to work with Amazon, with Zillow and other companies in Seattle who really stepped up.”

The result? A gleaming 135,000-square-foot facility that doubled the Allen School’s physical space, enabling the school to educate many more students—the vast majority of whom will be from the state of Washington. And it was completed not a moment too soon; today, the Allen School is approaching 1,800 students and has roughly 75 full-time faculty—and counting.

“It is a program that just keeps growing,” says Lisa Simonyi. “It’s vital to support that. The Gates Center is a new landmark.”

A public-private partnership funded the $110 million price tag on the new Gates Center building. Contributors included UW, the state Legislature, major tech companies, the Madrona Venture Groip and more than 500 individuals. (PHOTO BY MARK STONE)

Bill Gates shares a laugh with Washington Gov. Jay Inslee and UW President Ana Mari Cauce at the dedication ceremony for the Bill & Melinda Gates Center for Computer Science & Engineering. (Photo by Matt Hagen)

The main floor, designed to accommodate undergraduates, features a café, labs, meeting rooms and a student services center. But a 20-foot interactive wall, pictured at right, steals the show. (Photo by MARK STONE)

Computer science & engineering had humble beginnings at the UW. In 1967, it started as an inter-college graduate program known as the Computer Science Group, before becoming an official department in 1975, when an undergraduate program in computer science was added. A second undergraduate program, in computer engineering, was added in 1989 when the department was moved to the College of Engineering.

In 2017—the program’s 50th anniversary year—the Board of Regents voted to create the Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering, a move that elevated the program’s status within the University and forever linked the school with Allen, the beloved visionary who used UW computer labs long ago and was a generous supporter of the University in countless ways until his untimely death in October.

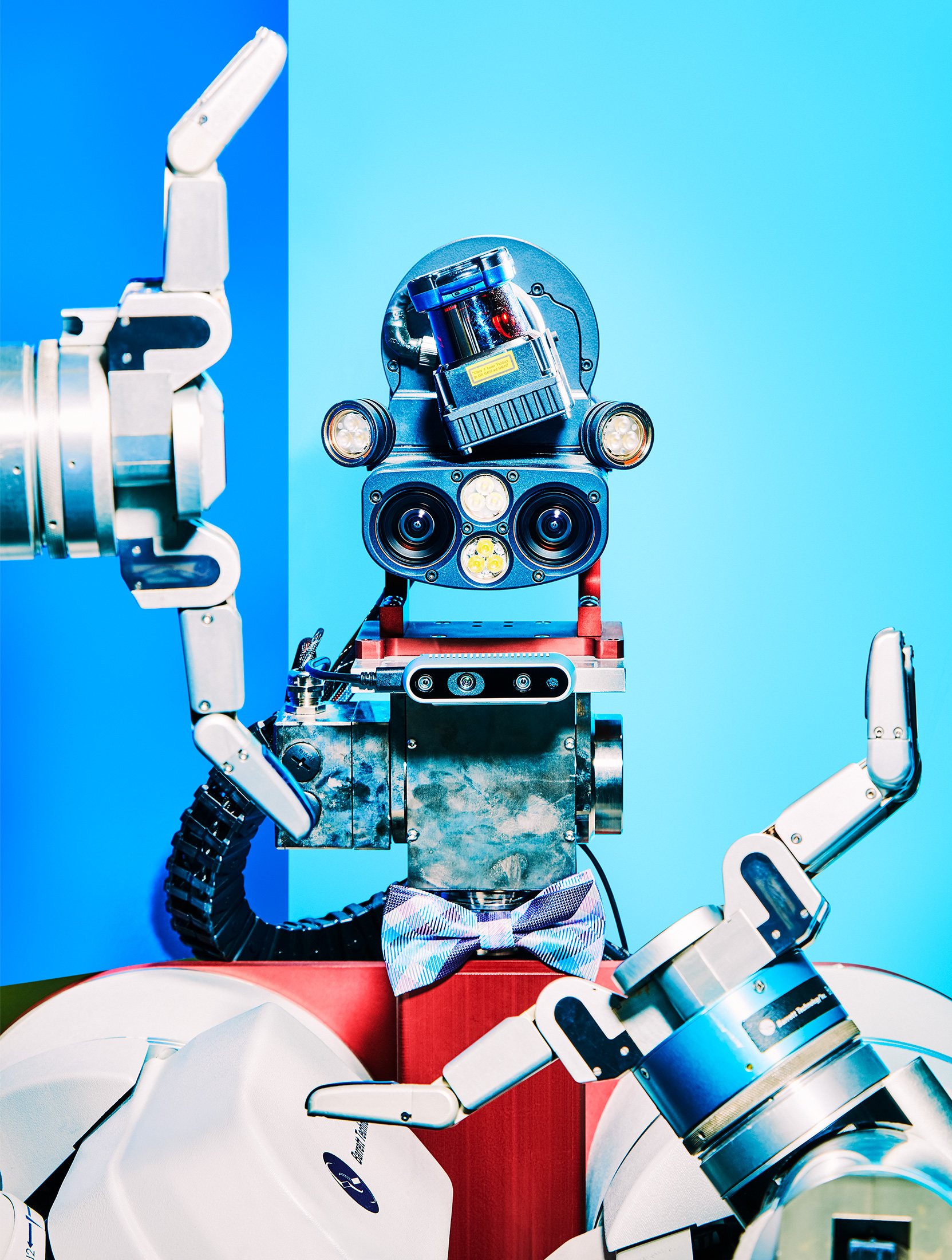

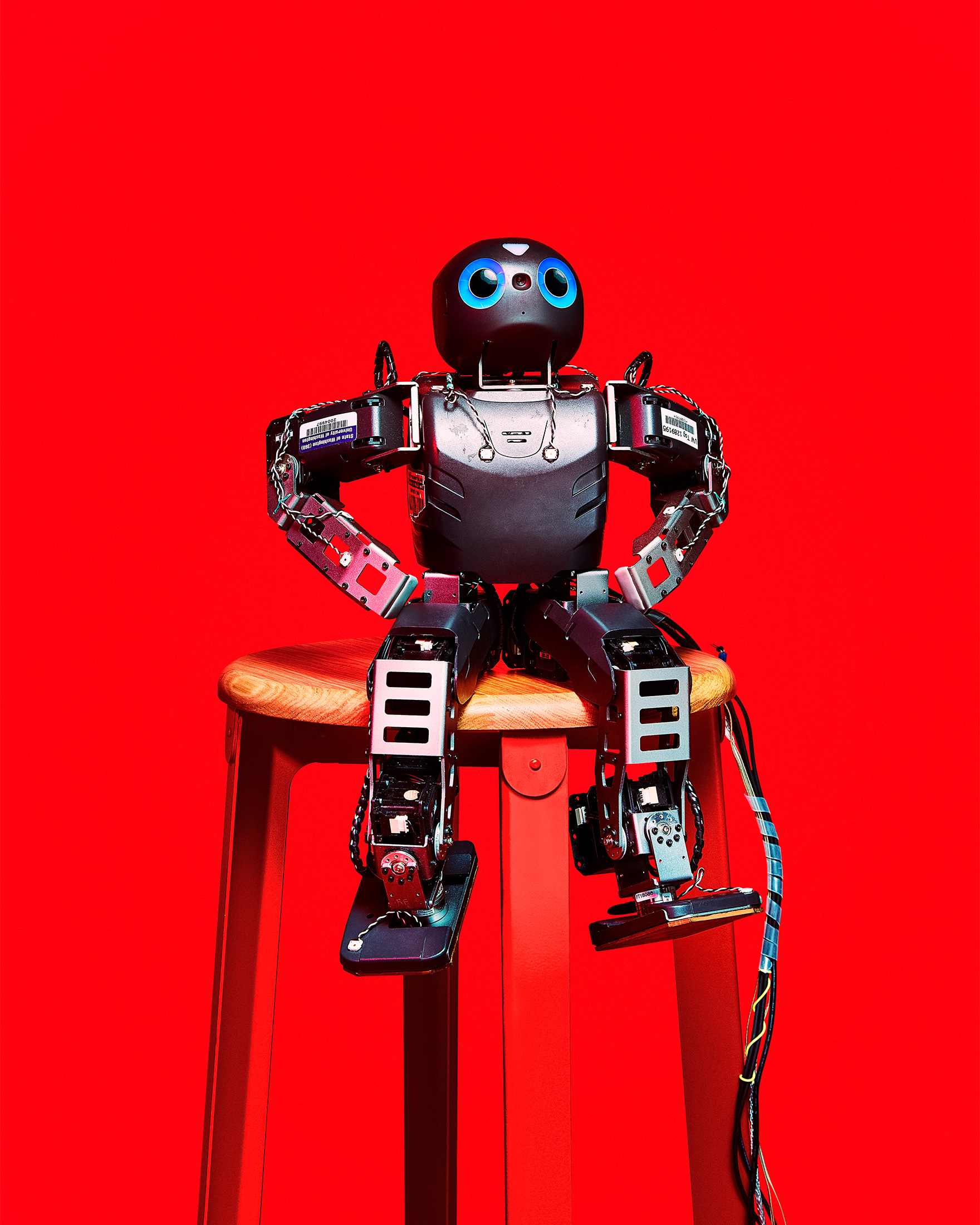

The expansion of computer science at UW coincided with its rising stature, and today, the Allen School is renowned as one of the very top computer science programs in the nation, not to mention one of the top suppliers of talent to such firms as Microsoft, Amazon and Google. Inside the new robotics laboratory on the ground floor of the Gates Center, students are exploring ways computing systems can work in concert with humans and replicate human actions.

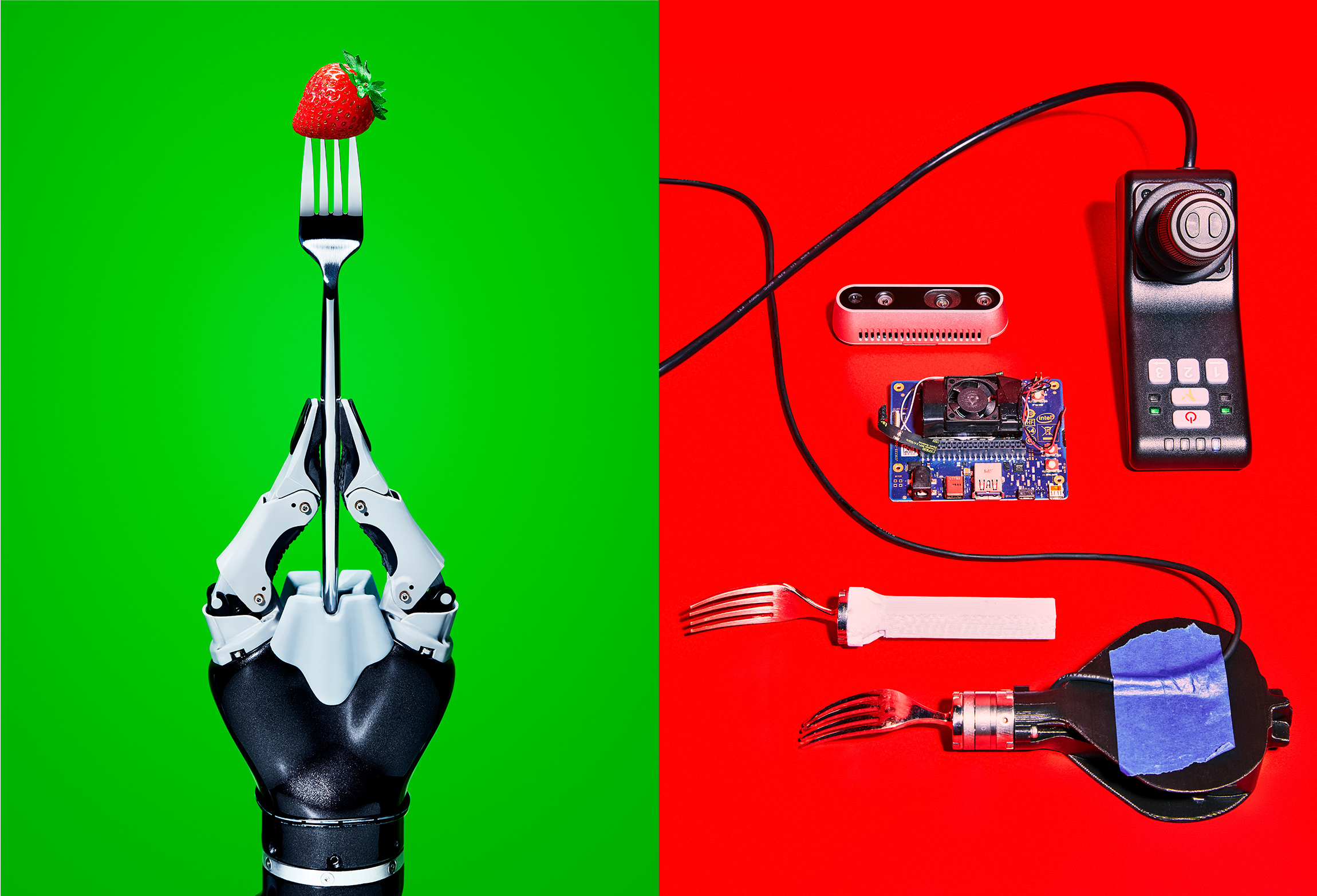

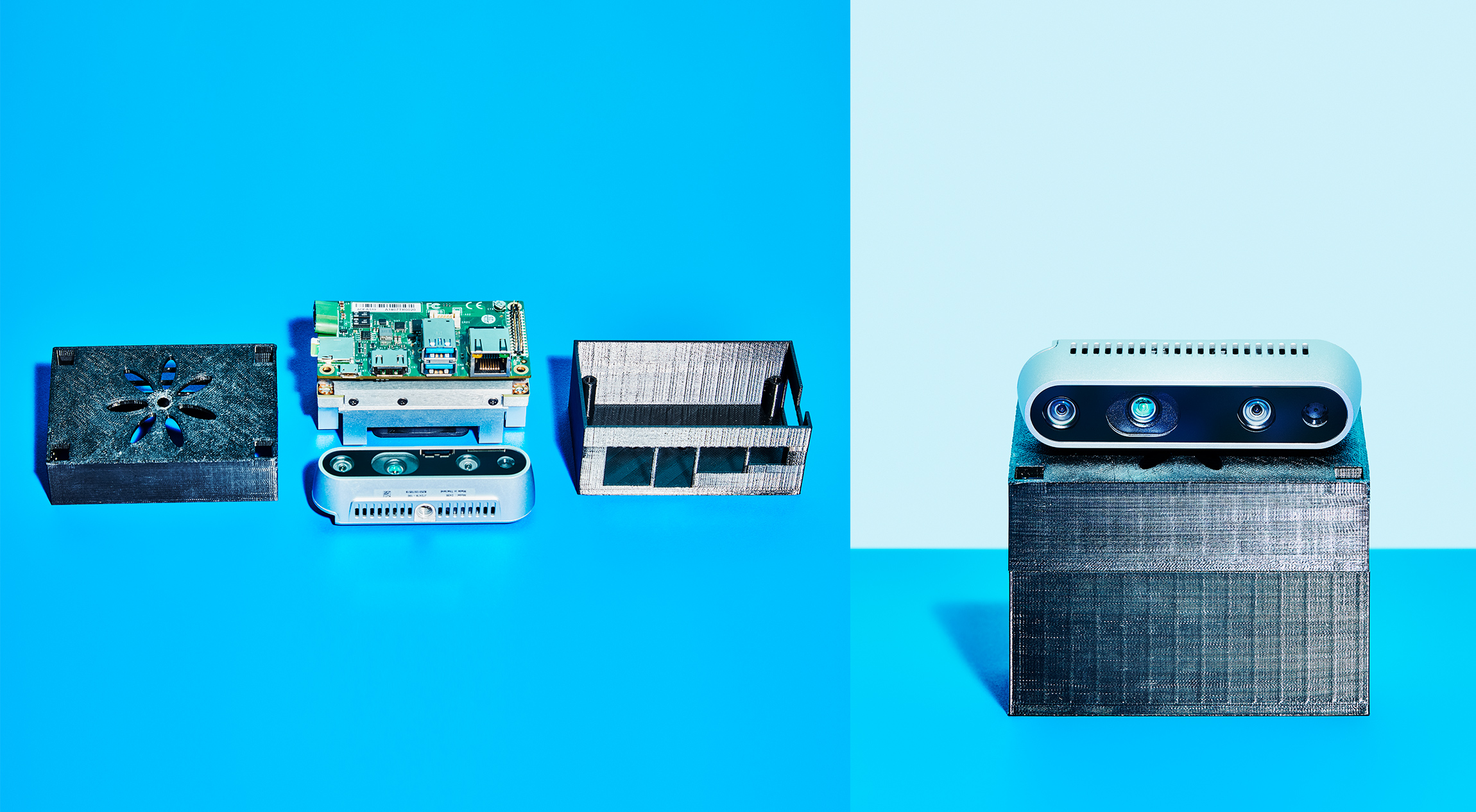

For example, UW researchers have developed an autonomous feeding system using a robotic arm that attaches to a wheelchair, with a robotic hand that can operate a fork. The arm was developed by a company called Kinova. But the feeding system that runs the arm was developed here. It means individuals with physical challenges, for maybe the first time, can feed themselves.

“The building is a fantastic place, but what’s really important is what goes on inside—the teaching, the learning and the research,” says Smith.

Other unique facilities enable the UW to push the frontiers of the field and deepen connections with the local technology community. They include a wet lab to advance the interface of computer science and biology, in a partnership with Microsoft Research; a fabrication research lab for exploring new approaches to rapid prototyping and computational design for manufacturing; and the aforementioned robotics lab, outfitted with a kitchen that supports the development of robots capable of assisting people with everyday tasks.

Beyond the technical, though, is another innovative touch rarely seen in such facilities: spaces to gather, collaborate and create a sense of community. The building is designed to get people out from behind their computer screens and foster the kind of serendipitous interactions that lead to new ideas. Examples include a main floor devoted to undergraduate students, including the Charles & Lisa Simonyi Undergraduate Commons—a gathering space with casual seating areas, a kitchenette, and meeting and project rooms—and the Silverberg Family Student Services Center, which offers a one-stop shop for academic and career advice. “Our No. 1 goal for the building was to create a warm and welcoming environment for a diverse student population—spaces in which people would enjoy spending time,” explains Hank Levy, Wissner-Slivka Chair and Director of the Allen School.

That includes occupants like Melanie Mendoza, a senior majoring in Computer Engineering. “You can really feel the thought and care that went into its design,” she says. “Having a designated capstone lab was particularly useful when I took the robotics capstone last quarter, as our group was able to focus on our project without having to worry about where we were going to meet, where to store equipment for our project, and especially for our capstone, where to create a controlled environment for our robot.”

The facilities are here. The next challenge? “To manage the growth of our program and increase the number of students we serve in a way that preserves our culture and enhances our excellence, fulfilling the expectations that Paul Allen had for us when he endowed the Paul G. Allen School,” Lazowska says. “It is a great responsibility—and a terrific opportunity for our university and our region.”