Death dodger Death dodger Death dodger

Taking risks was second nature for Albert Scott Crossfield. That’s how he became the first man to fly at twice the speed of sound and laid the groundwork to go into space.

Taking risks was second nature for Albert Scott Crossfield. That’s how he became the first man to fly at twice the speed of sound and laid the groundwork to go into space.

Cold December rain swept the remote airfield at Kitty Hawk, N.C. Worry showed in the eyes of test pilot Scott Crossfield, ’49, ’50. He won fame in 1953 as the first man to fly twice the speed of sound. Six years later he piloted the hypersonic X-15 spaceplane. Reporters gave the cocky Crossfield the ultimate nickname—“Mr. Space.”

Now at the age of 82, he faced a new challenge. He had spent four years training pilots to handle another experimental airplane—a replica of the 1903 Flyer, which Orville Wright flew 120 feet 100 years earlier in 1903. Today at a centennial event, it might fly for the first time as President Bush and thousands of spectators looked on.

Crossfield had, as Tom Wolfe put it in “The Right Stuff,” just that—“the ability to go up in a hurtling piece of machinery and put his hide on the line and then have the moxie, the reflexes, the experience, the coolness, to pull back in the last yawning moment—and then go up again the next day, and the next day, and every day.” Wolfe later told The Los Angeles Times that “Crossfield is the great man who nobody knows anymore [who should be] on the Mount Rushmore for pilots.”

Scott Crossfield scopes out the cockpit of an X-15 rocket plane at the North American Aviation plant in Los Angeles. Crossfield hit a speed of Mach 2.97 in the X-15. Photo by Allan Grant/The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images.

Today, as before, the eyes of the nation were on him. When he strapped into the sleek, sinister X-15 on June 8, 1959, for its first flight, America craved a post-Sputnik space-race victory. “We understood we were under the gun to do something for our country and get back our internal self-confidence,” Crossfield said.

Crossfield watched technicians tinker with the antique craft. “You wait and wait and wait. The engines don’t start. The airplane doesn’t work. You’re a month late. Everybody’s on your back,” said Crossfield. “This is the story of my life in flight testing.”

On this bitter morning the plane couldn’t fly. Not enough wind. The replica sputtered to a sandy halt at the end of its rickety launch track.

After testing an earlier model—a 1902 Wright Brothers glider—and surviving a crash four years earlier, Crossfield muttered, “I’ve never flown an airplane as unstable as this.”

No one ordered him to fly the thing—he volunteered. “We didn’t know what the limits of the airplane were,” said Crossfield. “I wasn’t going to ask pilots to do something I wouldn’t do myself.”

He had flown it several times at the end of a tow rope over a grassy runway, each time pushing its performance. One time while 10 feet high going 25 mph., he lost control. Though unharmed, “he went flying ass-over-teacup over the front of the glider,” said Virginia Tech engineering professor Kevin Kochersberger, who attempted the centennial flight.

Years earlier, Crossfield said he prided himself on never bailing out. “It’s a matter of professional integrity, if you please, to get it home—that’s what I’m paid for,” he said.

* * *

Photoillustration by Curtis Dickie

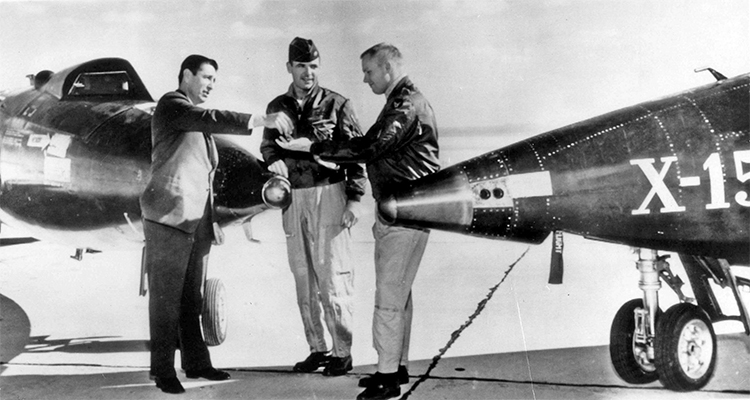

NASA test pilot Neil Armstrong (right) receives the keys to an X-15 rocket plane from North American Aviation test pilot Scott Crossfield (left) as Major Robert White looks on during a meeting of three of America’s premier test pilots in 1961. Photo by Rolls Press/Popperphoto via Getty Images.

In 1927—the year Charles Lindbergh made his historic solo crossing of the Atlantic—a priest arrived at Crossfield’s Wilmington, California, home to administer last rites. Six-year-old Scott had pneumonia and was in a coma. Pictures of airplanes blanketed the walls of his bedroom, almost covering an image of the Sacred Heart. “But what about the Lord?” he asked Crossfield’s parents.

A year after recovering from pneumonia, he came down with rheumatic fever. He had to stay in bed for months. During the next four years, the small, sickly boy was confined to bed-rest for weeks.

“I grew to adolescence in an unusual, isolated environment, finding things to pass the long hours at rest that few other boys do,” he recalled. When he was 9, he rigged a make-believe airplane control stick and rudder pedals to a wicker chair. With a flying manual beside him, “my imagination took me across oceans, into deep valleys and above the mountains. I dreamed of flying from California to New York nonstop and setting a new record,” he wrote in his autobiography “Always Another Dawn.”

Three years later, he got a newspaper delivery route. One stop was a small airfield. He offered the owner free papers in exchange for flying lessons. He never told his parents. For Crossfield, “each flight was a fantastic, wonderful experience, and a tonic.” At age 13, he knew his life’s goal: “I would be not only a pilot but the best damned pilot in the world.”

Around this time, his father bought a dairy farm near Chehalis in Boistfort, Lewis County. Thanks to his chores, Crossfield became a tough teen. After a high school fight, the principal told him, “Scott, don’t wait for the school bus today. Just walk on home right now.”

“I kind of felt I was the first astronaut or at least was way ahead of them.”

Scott Crossfield in a 1981 interview

As a University of Washington freshman in 1940, Crossfield was a young man in a hurry who wanted to be an engineer so he could understand every aspect of aviation. “A lone wolf on a special mission,” he called himself. He took a heavy course load, lived in “depressing” boarding houses, and worked as a butler and furnace cleaner at a “snooty sorority.”

Returning to UW after World War II—a Navy fighter pilot, he flew the Vaught Corsair but never saw action—Crossfield got his bachelor’s in science in 1949 and flew, so to speak, through his graduate studies, earning his master’s in aeronautical engineering in a year while relishing his job as chief operator of the UW’s Kirsten Wind Tunnel. His thesis, which he bragged might have fewer pages than any other, focused on aviation’s future—swept-wing supersonic aircraft. “He was forward-looking, a driven man,” says former department chair Adam Bruckner.

While finishing school in the UW’s William E. Boeing Department of Aeronautics & Astronautics, he wrote a letter seeking work at Bell Aircraft, maker of the X-1, which broke the sound barrier in 1947. It concluded: “Temperament: reliable, family-man type; even disposition, cool in emergencies. Salary? I would fly the X-1 for nothing, if necessary.”

Receiving no reply, he made an unannounced visit to the chief pilot at the Ames Research Center in San Francisco. He told Crossfield he had no openings but that by odd coincidence, Crossfield’s wife had just called to tell him that her husband had been invited to Edwards, the California test center for experimental aircraft near Death Valley, to interview for a test pilot job at NASA’s predecessor, NACA, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics. There, Crossfield said he found “a runway scratched out of the desert” and fliers with a “contagious, pioneering spirit.” He found his destiny.

* * *

President John F. Kennedy meets with a group of X-15 test pilots at a ceremony presenting them with the Harmon Trophy Award on Dec. 1, 1961. Pilots (L-R) Scott Crossfield, Joseph A. Walker and Major Robert M. White received the honor as the world’s outstanding aviators for 1960. Photo by Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

“We’d test the edge of something and find out we were in the middle of a whirlpool,” he told the Royal Aeronautical Society in 1979. His dangerous, yet routine, high-altitude research work meant learning a rocket plane’s limits, landing alive, writing a report and maybe breaking a record in the process. Before the X-15, Crossfield flew more than 100 sky-shredding experimental missions—more hours than any other test pilot—in the X-1, X-4, X-5, XF-92, and the D-558 II Skyrocket, the bullet-shaped white plane he took to Mach 2 (1,291 mph) on Nov. 20, 1953.

He routinely dodged death. On his first X-4 flight, both engines failed. “All hell broke loose at 27,000 feet,” he recalled. The Skyrocket, also on his first flight, lost power, instruments and cabin pressure. As if that wasn’t enough, the windshield iced over, and the cockpit filled with smoke. Once when flying the X-1, which he called “the king of the hot rods,” it pitched, stalled and flipped on its back. Its windshield also iced up. Crossfield “thanked his lucky stars” he wasn’t wearing flight boots. He kicked off an oxford shoe, yanked off a sock, and scraped clear a spot in the windshield with his bare foot.

Then came the X-15, a plane Air & Space Magazine dubbed “the keystone in the bridge between Earth and space.” Crossfield called it the first manned space vehicle. “I kind of felt I was the first astronaut or at least was way ahead of them,” he told NBC in 1981.

The X-15, which Crossfield referred to as “a strange tiger,” was a black dart snuggled under the right wing of a B-52, lofted to high altitude, and dropped to the perilous unknown so its million-horsepower rockets could blast into the heavens and land safely, a feat it did 199 times more than 20 years before the space shuttle.

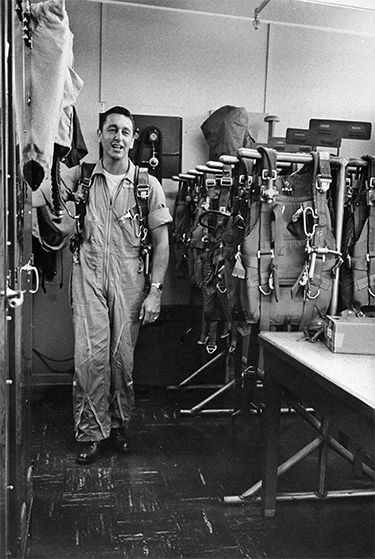

Test pilot Scott Crossfield joins a rack of flight suits and other gear inside the pilot dressing room at the North American Aviation plant in Los Angeles. Photo by Allan Grant/The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images.

Crossfield was the perfect pilot. “He was the first of a new generation of flying aeronautical engineers—an engineer first and pilot second,” says National Air and Space Museum curator Bob Van der Linden. Like Neil Armstrong, who later flew the X-15, Crossfield had the flying skill and steely nerves, plus an engineer’s intuition about human factors and aerodynamics.

Like the Wright Brothers, he was an inventor. Not only did Crossfield help brainstorm the X-15 in 1952, he left NACA in 1955 to work for North American Aviation as its Design Specialist and pilot. “I would be the X-15’s chief son of a bitch … anyone who wanted … to capriciously change anything or add anything … would have to fight me first,” he said.

“The engineers were in virgin territory,” according to National Air and Space Museum curator John Anderson, author of the book “X-15.” The space plane’s pioneering design had temperature-ablating metals on its leading edges to act as re-entry heat shields. The X-15 remains one of the most successful research planes ever built, its Mach 6.7 (4,520 mph) speed record unbroken.

Crossfield also designed the first full-pressure suit in collaboration with a Philadelphia girdle maker. He saw a “glamorous looking” shiny silver fabric at the company and recommended that it replace the khaki space suits for an iconic, futuristic look. When the Pentagon wanted heavy material for the X-15’s seat, Crossfield fought back. Remembering his farm-boy days, he had already contacted International Harvester and had a lighter seat modeled after those on tractors.

Crossfield was a visionary in other ways. In 1952, he suggested attaching an X-15 to the top of a rocket to create an orbital space plane, a strategy NASA formally rejected in 1959. “If we’d continued with the orbital X-15, it would’ve been the research airplane’s natural step up the line,” Crossfield told the Discovery Channel in 1993. “We wouldn’t be worrying about space stations today, they’d be up there.”

Mishaps plagued the X-15. On its first non-powered glider flight, ice frosted its windshield. (On later missions, a plastic windshield scraper would be hung on the control panel.) During the first powered flight on Sept. 17, 1959, Crossfield struggled to land as its nose rose and fell like a rowboat’s bow in stormy seas. Fellow X-15 pilot Milt Thompson, ’53, called it “a terrifying sight.” Crossfield barely touched down safely. His reward on landing? In true 1950s style, an Air Force officer handed him a martini with an olive.

“The thought of a bailout never occurred to me. I’m paid to bring airplanes back, not throw them away.”

Scott Crossfield, in writings

On the third powered flight, the X-15 caught fire after its rockets exploded at 45,000 feet. “The thought of a bailout never occurred to me. I’m paid to bring airplanes back, not throw them away,” he wrote. Unable to jettison fuel, he landed heavy, causing the X-15 crash land and snap in half.

The flight surgeon, thinking he heard someone radio that Crossfield had broken his back, tried to yank him out. Fearing excessive canopy motion would arm the ejection seat—and unable to communicate because of his helmet—Crossfield battled the doctor for the canopy. “He did not want to be ejected accidentally after surviving an explosion, a fire, and an emergency landing,” Thompson recalled.

When the X-15 got a new, more powerful engine, Crossfield buckled in for a ground test, huge steel clamps restraining his “tiger.” He started the engines and shut them down. When he restarted them, “it was like pushing the plunger on a dynamite detonator,” he recalled. Sixteen thousand pounds of ammonia and hydrogen peroxide exploded, hurling Crossfield and the cockpit 20 feet forward at an estimated 50 Gs. “There was no panic, no fear,” he said. “I was concerned primarily for the safety of other people.”

He joked that flight surgeons loved doing autopsies on test pilots because they were so easy. “When you opened up a test pilot,” Crossfield said, “you found only two operable parts—one at each end and totally interchangeable.”

Contrary to popular belief, test pilots were nearly as famous as Mercury astronauts. After his Mach 2 flight, he was mobbed at a hotel press conference, flashbulbs exploding in his face. Later he found himself seated with movie star Esther Williams. When asked what she thought about being next to the world’s fastest man, she replied, “He hasn’t laid a hand on me yet.”

During his X-15 days the press dubbed him “Our First Man in Outer Space,” even though none of his flights flew that high. “The press refused or couldn’t bring itself to believe me,” he said. “It was always the same: hurry, impatience, no time for thoughtful reflection.”

Because Crossfield worked for North American Aviation, NASA forbade him to push the X-15 to speed and altitude limits reserved for military pilots. Years later, the space agency retroactively gave test pilots who flew above 264,000 feet (50 miles) the title “astronaut.” Crossfield wasn’t eligible. His peak altitude and speeds were 88,116 feet and Mach 2.97 (1,960 mph), though he told friends he violated his orders and punched past Mach 3.

He considered applying for the Mercury program, but an Air Force general told him, according to Wolfe, “Scotty, don’t even bother, because you’ll only be turned down. You’re too independent.” The deciding blow came when he learned the honor of the first flight would go to a chimp.

In the end, he played a major role getting men to the moon. As a systems director at North American Aviation on the Apollo program, he oversaw reliability engineering, quality assurance and systems tests for the command and service modules and the Saturn V’s second stage. Later, he became an Eastern Airlines executive and for 20 years served as a consultant to the House Committee on Science and Technology.

He continued to fly. On April 19, 2006, when he was 84, he left the Prattville, Alabama, airport in his vintage Cessna 210A to fly home to Manassas, Virginia. He hit a Level 6 thunderstorm in northwest Georgia. In his last transmission to air-traffic control, he requested a 180-degree turn. Searchers found his plane’s wreckage in the foothills of the Smoky Mountains. An investigation blamed the crash on his failure to get updated weather information and controllers’ failure to warn him of the storm.

Crossfield loved risk. In his later years, he railed that bureaucracy had stifled progress. Of his early Edwards days, he said “we had an era where we could do pretty much what we wanted. We would stay up late at night figuring out how we wanted to do something, and then we’d go out and do it. Who’s to stop you?

“Our only risk,” he said, “is the fear of risk.”

At top left: Test pilot Scott Crossfield tries out a pressure suit in a heat chamber in an undated photo from the 1950s. Photo from Bettmann Collection, Getty Images. At right, Crossfield poses with the X-15 rocket plane in Los Angeles in October 1958. Photo by Allan Grant/The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images.