The fall (and rise?) of ‘the Ave.’ The fall (and rise?) of ‘the Ave.’ The fall (and rise?) of ‘the Ave.’

Once Seattle's second Main Street, the Ave. has fallen on hard times. Can the UW and the community save what's left?

Once Seattle's second Main Street, the Ave. has fallen on hard times. Can the UW and the community save what's left?

The intoxicating aroma of fresh, hot pizza relentlessly wafts from the open storefront window of Pizza Brava as three crimson-haired, body-pierced, black-booted, bare-bellybuttoned girls stroll by, listening to Nirvana cranked up to about 900 decibels.

A few feet away, a forlorn man leans against the wall outside University Grocery. Three pennies lay in the large, flat cardboard box lid in his left hand. He looks wistfully at passersby, hoping for handouts.

Walking up the long, grey ramp from the below-grade University Station Post Office, two bearded, 35-ish men share their anxiety about finding out what graduate schools they got into, as a busker with a guitar plays out-of-tune songs.

Welcome to University Way NE. You probably know it better as the “Ave.” For the past few years, it has been known as a hip, fun, funky street that is going downhill.

The Ave. in 1956. Photo courtesy of First Interstate Bank.

Set up by Seattle’s pioneers as the city’s second main street before the turn of the century, University Way NE today sadly bears little resemblance to its old self. Once a thriving business corridor, with electric trolley cars, it was home to a whole generation of mom-and-pop shops, like Carter’s Deli (where McDonald’s now is), where you could get a pound of “lean” and the shopkeeper would ask how your kids were doing.

There was a bowling alley, a deli, a funeral parlor, an interior design store, Nordstrom, JC Penney, The Limited and Athlete’s Foot. But they are long gone, having bolted for places like Northgate Mall or University Village, driven out by sky-high leases, a flood of street people and lagging sales. Now the Ave. is dominated by fast-food joints, used book shops, penny stores, copy shops and the like. Empty storefronts are as common as the skateboarding street kids and homeless people who clog the oh-so-narrow sidewalks, begging for money and just hanging out.

“Nice people are gone; it’s like a jungle on the Avenue,” says Warren Porter, owner of Porter-Jensen Jewelers, which has been at the corner of NE 45th Street and University Way NE for decades. Headlines echoed the lament: “The `U’ District remains a developer’s nightmare,” screamed the Puget Sound Business Journal in early 1995.

But putting aside all the bad press, there is one truth that has become a much-repeated phrase summing up the Ave.’s decline: You can’t buy underwear or socks on the Ave.

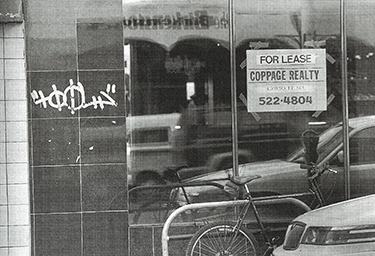

Vacant storefronts have become commonplace on the Ave.

“The whole feeling of the place has changed,” says Cal McCune, ’36, whose law firm has been a University District mainstay for the past 50 years, “but this place still has an awful lot to offer. And it can get even better.”

While many have held that belief, only now have merchants, neighborhood residents and city officials put aside their fractious ways to work together in making the Ave. a better place.

“You could say people around here are very opinionated,” says James Conlin, ’87, ’91, a `U’ District lawyer and community activist. “Different people have different causes. We couldn’t agree.”

Many people do agree—especially older UW alumni—that the Ave. was once a very special place.

The Ave. got its nickname in 1919, when the street was officially known as 14th Avenue NE. Locals felt a numbered street was not a suitable name for the principal business street in the University District, and gave it a pet name. Later, the University Herald ran a contest seeking suggestions for new names, and the street became anointed University Way NE.

A hundred years after moving to the district and a hundred yards to the west, the UW is taking an increasing role in its relationship to the Ave., something Christine Cassidy, ’72, who heads up the Greater University Chamber of Commerce, says is essential. “We are the front door and the backyard for the UW,” she maintains.

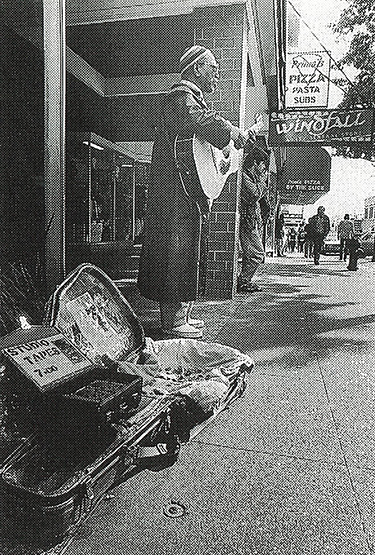

Guitarist Ron Martinez has been a fixture on the Ave. for years.

The Cascadia Community and Environment Institute, which operates out of the UW School of Architecture, held a recent series of forums addressing various aspects of the Ave. Inviting more than 40 expert architects, urban planners, community leaders and other officials, Cascadia Institute examined such issues as housing, interaction between the UW, the Ave. and U District, and transportation.

“One of Cascadia’s goals is to help the community create a successful vision of its future,” says Anne Vernez Moudon, director of the institute and an associate dean in the School of Architecture. “Historically, planning in the University District has been riddled with opposition, and in the last 10 years, the neighborhood, and the Ave., have suffered.”

Doug Kelbaugh knows that only too well. A resident of nearby Roanoke Park for the past eight years, he comes to the Ave. two or three times a week to grab a bite, get copies made, shop the used book stores, find a gift. He also has another perspective, as a UW professor of architecture who last year conducted a “design charrette,” where four teams of architecture students spent five days brainstorming about the Ave. and coming up with suggestions for improvements.

The teams worked closely with community groups and leaders who have been involved with Ave. issues for years, as well as transportation planners and city land use and construction personnel.

“I like the earthy quality of the Ave., but it has gone a little too far,” says Kelbaugh. “It is good in that it embraces all groups, it has a vitality you won’t find in the suburbs. People of all walks of life rub shoulders here, and we are lucky to have an urban fabric and city life next to our bucolic campus.”

Two street people, who asked not to be identified, hang out on the Ave.

Kelbaugh’s charrette teams made numerous suggestions, from calling for low-rise multifamily units in residential neighborhoods north of 45th and west of the Ave, to revising traffic patterns, to designing housing in the University Book Store parking lot. Some called for underground subway lines along 15th, vertical signage along the Ave., creating more businesses in alley ways, and on and on.

Though the four teams had different solutions, Kelbaugh says the Ave. needs apartments above shops, with buildings as tall as 2-3 stories; more offices and research institutions in the area; and light rail serving the area.

He especially sees housing as the key for the Ave. and the University District, which has a high 90 percent rate of renters. “The University District is an underserved city core,” he explains. “We need a lot more housing there, on the Ave, along 15th, Brooklyn. This could be a thriving area.

“The area could stand a lot more density in housing. It is one way to fight urban sprawl. And if you had more stable housing, in terms of more families and faculty living here, then that would attract the retailers.”

Some argue the other way around, that having better retail stores and restaurants is the way to draw people. “But retailers can’t be asked to take on all the risk,” says Kelbaugh.

“This is where people should live. This is a major hub of transportation and the University. There is a lot of land, too many parking lots, and there is no reason this district hasn’t taken off like other districts through Seattle.”

“When you look at places like Fremont, Greenwood and Queen Anne,” says Patty Whistler, head of The Ave. Planning Group, a citizen panel that came together in 1994 to develop a revitalization strategy for the Ave., “we are dying on the vine.”

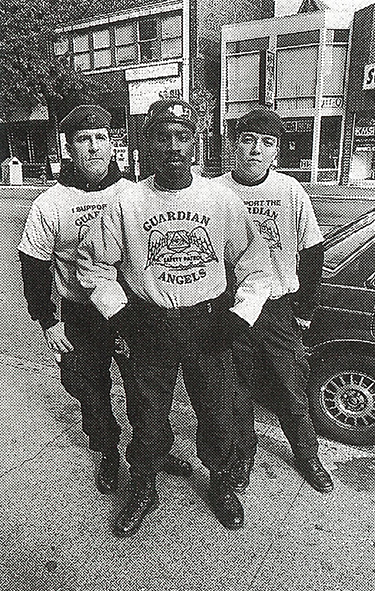

Guardian Angels Mike, Charles and Zoe patrol the Ave.

But no matter the vision, Bob Cross wonders how these plans will actually be put into use. As the general manager of the University Book Store—the Ave.’s acknowledged main anchor for the past six decades—he has seen a lot.

“It takes money to accomplish these goals,” he says. “Where will it come from?

“I do think the Ave., while not unsafe, is an uncomfortable place to be. Those who don’t need to come here, don’t. But who is going to pay for all the ideas to become reality?”

Kelbaugh sees a stronger University presence as a big help. “Instead of things like car dealerships on Roosevelt, why not University-related uses. That would enhance the area, and give it more of an identity.”

Of course, part of the Ave.’s problem is purely physical: by running parallel to the campus, it has no direct link to university grounds. In contrast, some of the more famous streets in college areas—Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley, Calif.; State Street in Madison, Wis.; and Westwood Boulevard in Los Angeles—feed directly into the campus.

Without a direct link, the flow of people from campus to the Ave. isn’t nearly as great as one might think. It attracts students, but the people on campus with money—faculty and staff—rarely come onto the Ave. to shop, a recent marketing survey found out, much to just about everyone’s surprise.

The decline of the Ave. has many roots: increasing rents for business owners, the opening of malls and shopping centers like University Village in 1970 (and its subsequent lure of major stores that once used to be on the Ave., or would have located there), migration of families from the University District, the closure of the local elementary school, and the flood of street kids and homeless people to the area. And the caliber of stores that left the Ave. in the ’60s, ’70s’ and ’80s—such as Miller Pollard—never came back, instead of being replaced by those catering to the street crowd.

“The change in the Ave.,” explains Scott Soules, ’71, a third-generation Ave. property owner and commercial real estate agent, “also has to do with economic and social forces much greater than this street.

“People’s shopping habits have changed. That is just the nature of retail business. I know for people who went to the UW in the 1930s-1970s, they are sad because the Ave. changed. But I don’t see it ever going back to the way it was.”

In that vein, the UW is being looked upon somewhat differently these days. Before, “it was the 800-pound gorilla in the district,” says Carla Mayne, project manager of the city’s neighborhood planning office on The Ave. “The business community has seen the value of the University and depends on students, faculty and staff for a lot of its business.

“But the residents have been less comfortable, feeling that the University needed to be contained and restrained or it will take over.”

With rare community support, a plan for UW Extension to move its offices into the Ave. Arcade Building (formerly JC Penney’s) just north of 45th was given lots of hope. But the plan fell through in September when the city would not exempt the UW from its “lease lid,” which puts a cap on the amount of U District space that can be leased by the University. The UW decided against leasing just the upper floors of the building, saying it wanted a storefront presence.

Christine Curtis, ’73, a founder of the U District Farmers Market.

“That was an attempt for all of us to work together,” says Christine Knowles, the UW’s director of community affairs. “Our goal was to make the University more accessible, to have a street presence on the Ave., and create better interaction.

“Though this effort didn’t work, I think we have laid the groundwork for something like this to work next time around.

“The community has always had lots of concerns about the University and its impact but we are doing our part. We came up with the U-PASS program to address transportation and parking concerns.

“The bridge-building process with the community is continuing. The UW should be involved in upgrading its community.”

The UW Retirement Association was eager to develop housing in the University District for retired faculty and staff. One plan fell through in the autumn, and efforts have turned to Wallingford.

“It would have been a tremendous asset for the UW to reconnect with the Ave. through these kinds of projects,” says Cassidy. “I think the linking of the Ave. to the University is crucial. The community feeling about the University has changed, and we need to reinforce the connection with the University and create an identity for the Ave. and the area.”

Indeed, the University’s role in the community has long been a hot button. The city and the UW haven’t always seen eye to eye. For instance, the city sued to stop expansion of the UW Medical Center in the 1980s. But that relationship has improved, especially under Mayor Norm Rice, ’72, ’74, who values the University and its role.

Alumni also play a huge role individually in their quest to make the Ave. a better place.

For instance, take Christine Curtis, ’73. For 10 years, she owned the popular Haagen Dazs ice cream store on the corner of the Ave. and NE 43rd Street. “I saw lots of changes,” she recalls. “Especially in the late ’80s, it was unfriendly, there were kids on the street. But since then, things are improving.”

In 1993, she opened the University District Farmer’s Market. Operating out of the University Heights school yard, the farmer’s market has become a source of neighborhood pride. When it opened, 17 farmers sold their wares to an opening day crowd of 800. Today, 45 farmers — there is also a waiting list — offer up farm-fresh produce, baked goods and other wares to nearly 3,000 folks on Saturday mornings from June to October.

“I wanted to give the Ave. a boost,” says Curtis, who spent nearly two years planning it. “It has served as a catalyst for the neighborhood. It works at an emotional level. It is a friendly way to shop, meet friends and talk.” They weren’t the only ones to come together. Business owners on the Ave. gave her lots of help, as did the chamber of commerce. The market pays no rent, and Curtis says that the market, which is seeing profits for the first time, will plow that money right back into the operation to provide things like an awning for rain protection, more chairs for people to sit and talk, and more vendor stands.

Cross, who attended the UW for three years but dropped out when he fell in love with working at the book store as a student, says that Ave. landowners hold a key in improving the Ave.

“We need a large proportion of Ave. property owners to invest in their properties,” he says. “There are some excellent property owners. But there are some who only think of their next rent check. There are some businesses on the Ave. that really ought not be here.”

Street kids haven’t been welcome, but Nanci Amidei, a UW professor of social work, has been working with that problem. She helps coordinate the University District-University Partnership for Youth, a coalition of organizations that deals with the escalating tensions over the growing presence of street kids in the business district and around the UW campus.

McCune, who has been involved in many U District projects over his 50 years in the area (for instance, he backed a failed 1969 effort to turn the Ave. into a shopping mall) says that the hardcore street people have to be dealt with, and that housing them in the district isn’t the answer.

Fixing the street’s sidewalks will be a good first step to any Ave. renewal. Ave. sidewalks are not only in bad shape, but they are only 8-9 feet wide, while city standards say sidewalks should be 14 feet wide. Another priority is getting money to improve street lighting.

But any light at the end of the tunnel will be shined in part by the UW. Says Knowles, the UW’s community affairs director, “Finding a way to allow UW activities into the district and open the campus up to the district is a key. There has to be joint support

“But we don’t need big solutions. Even things like wider sidewalks and better street lighting would serve us all better. Then we could work up to bigger things, such as the housing situation.

“But we need to do this as a partnership. The perception is that the UW is wealthy and can just do things. That isn’t the case. We can bring resources to the community, and we need to.”

“The UW is a city unto itself with 50,000 coming and going every day,” says Conlin, the University District lawyer who has been very active in district affairs for years. “It is an engine that will drive the Ave. forever.”