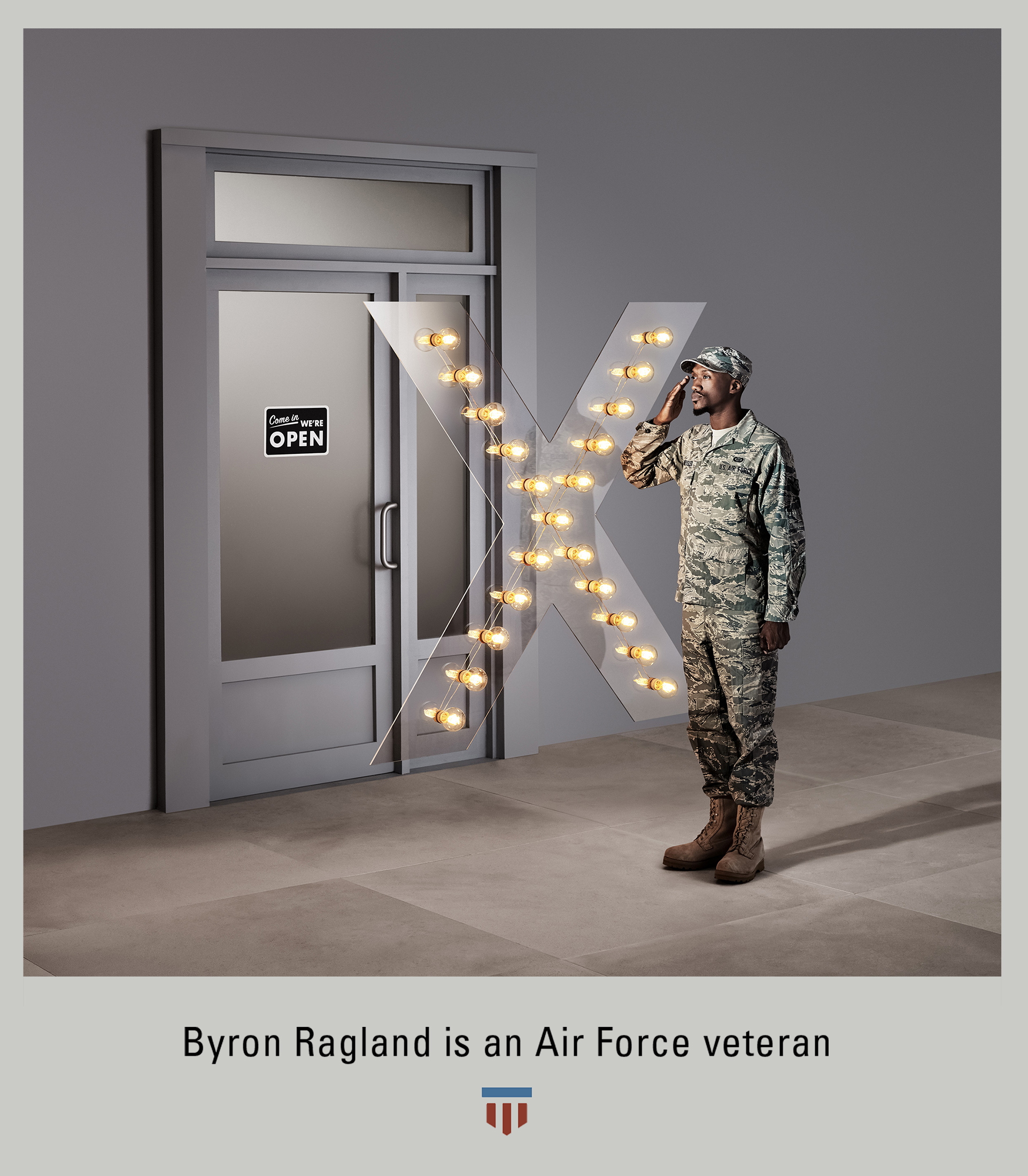

Byron Ragland is the youngest of three children and his parents’ only son. He has the wide-open smile and arms-length charm of an adored child who might be a bit tired of all the attention. With his straight posture and angular form, he looks like someone cut to fit a military uniform.

Ragland wore that uniform for nine years in the Air Force. He was stationed in Turkey, Qatar, Germany, South Korea and South Carolina. He repaired the machines that support planes ferrying supplies and troops in and out of combat zones. He spent a year in the honor guard, wearing dress blues and carrying the caskets of soldiers who served decades before he was born.

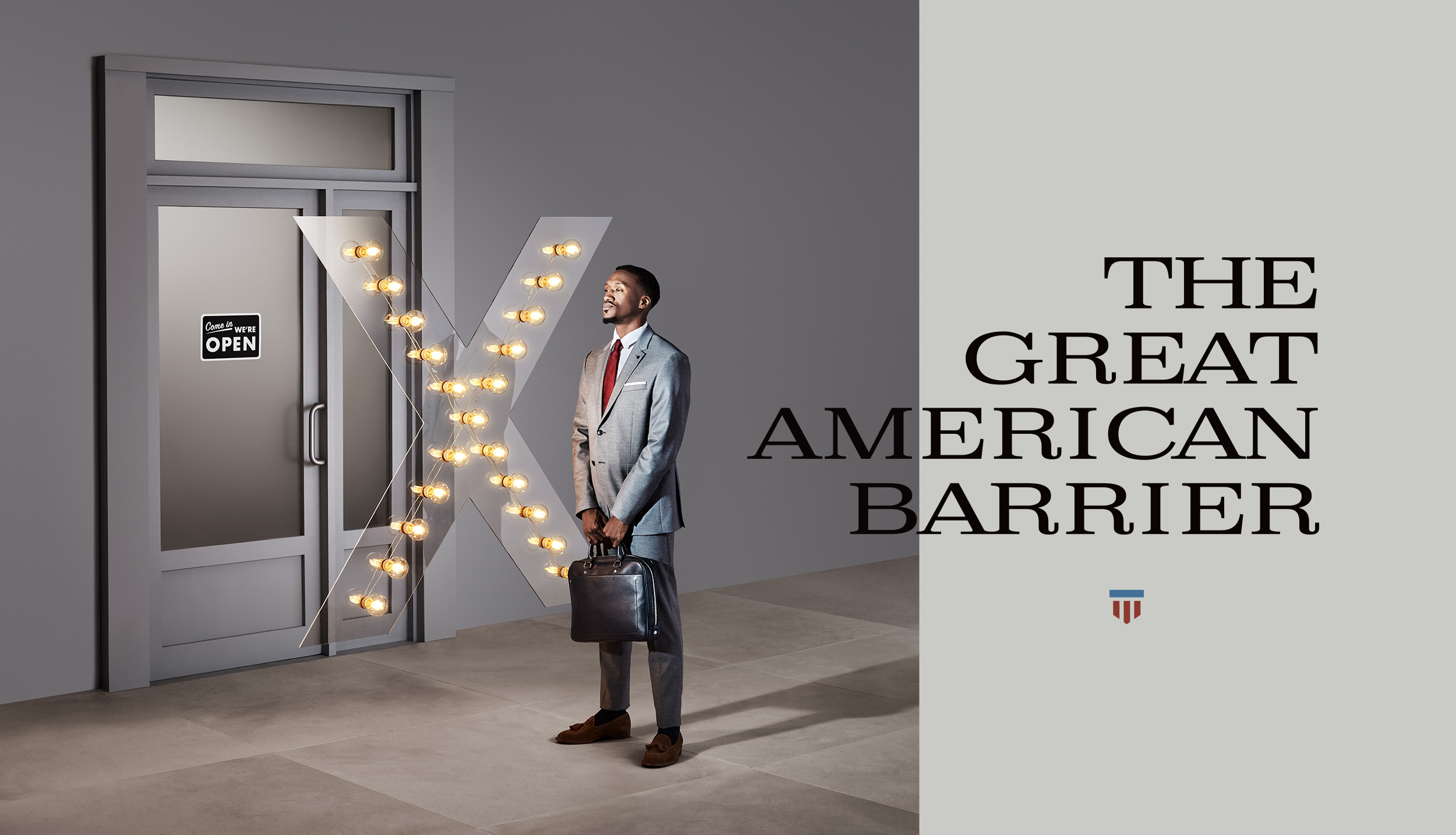

Five years ago, he came home and in 2017 enrolled at UW Tacoma to study psychology. And last November, Ragland sat down at a table in a frozen yogurt shop in Kirkland—a 31-year-old black man dressed in jeans and a sweater.

The chilly evening didn’t feel like ice cream weather, but that wasn’t his call. Ragland works for a private Seattle agency overseeing court-ordered visits for children and parents. He was in Kirkland with a mother and her 12-year-old son, regular clients attending their last required supervised meeting. After an hour or so at a local park, the three headed to the nearby Menchie’s Frozen Yogurt shop, where they often ended up. The shop’s cursive logo, round tables and menus create an effect as smooth and yielding as the soft-serve yogurt. A sign hanging in the window reads, “Beware: Opening this door may cause severe bouts of happiness.”

Byron Ragland served in the U.S. Air Force for nine years. Both his father and mother were in the Army and met while stationed in Germany.

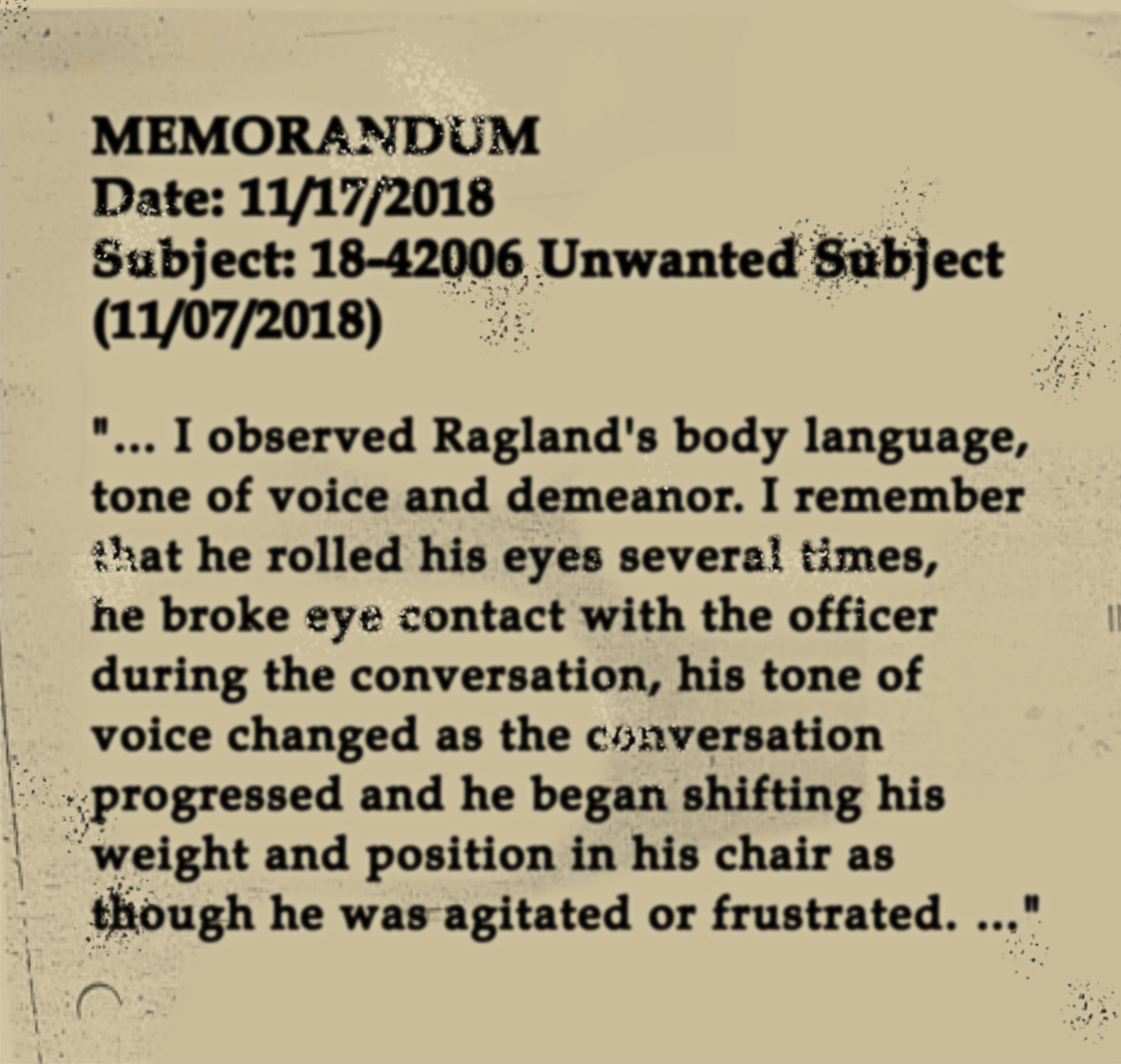

Ragland chose a table behind mother and son—close enough to log their interaction, but with enough space to let them be together. He took notes on his phone to document the visit, something he routinely did. After about 20 minutes, Ragland looked up and saw a police officer standing over him.

We need you to leave the premises.

A Menchie’s employee had called the shop’s owner about a suspicious man in the store. The owner checked the security footage and alerted police. “They’re kind of scared,” he said, according to a transcript of the 911 call. “He just keeps looking at the phone and looking at them.”

There’s no sound in the Menchie’s security video, which you can watch later in this article (it’s also posted on the Kirkland Police Department’s website). Like a silent film, it tells a story about the two-and-a-half minute encounter between Ragland and the police through hand gestures and body language. It’s clear who is in charge. Who feels threatened. Who feels safe taking up space. And who would prefer to disappear.

The officer walks in past the counter and over to Ragland, whose head is down as he types on his phone. Ragland extends his arm to shake the officer’s hand. A second officer enters the store and stands by the door, watching. The mother, who is white, turns around in her seat. “That’s wrong,” she said to the officer, according to the police report. “He didn’t do anything, and he is with me. He is here for a supervised visitation.” Ragland stays in his chair.

* * *

Don’t draw attention. Be nice. Be polite. Be quiet. Go in there, go out. Don’t be anywhere you’re not supposed to be. Don’t be standing around, talking to anybody you don’t know. Go in there. Come out.

He had a lot on his mind that afternoon at Menchie’s. He was worried about studying for finals and excited to visit his 7-year-old son in Missouri for Thanksgiving. As treasurer for the UW Tacoma Black Student Union, he started the day at a campus forum discussing the use of a racial slur.

“The second I look up and see these cops are talking to me, I was like, OK, let’s make it out of here,” Ragland says. “Let’s make it home tonight.” He was aware of the other possibilities. The Black Lives Matter movement and videos captured on cellphones have made public names his mom didn’t yet know. Sandra Bland. Michael Brown. Stephon Clark. Charleena Lyles. Eric Garner. Philando Castile.

Ragland grew up in Decatur, Georgia, a community close enough to Atlanta to attract the hallmarks of a gentrifying suburb over the past decade: microbreweries, rising home prices and a growing population of young white professionals. As a teenager, Decatur seemed more to him like a dead end. During his sophomore year in high school, Ragland joined the ROTC, not so much because he felt called to duty (that came later), but because the military offered a path out of Georgia, a chance to see other countries and a way to pay for college.

His mother, father, two sisters and two uncles all made the same choice when they were young. Ragland’s parents enlisted in the Army after high school and met while stationed in Germany, a few miles from the base where his son was born three decades later. His father grew up in Atlanta and recently retired after 30 years as a custodian for the local public school district. His mother, a financial planner, graduated from Garfield High School in Seattle.

“As a 10-year-old, you know what color you are,” Ragland says. “You know that you can be a target. Not a lot of black parents are letting their kids get to 10 without telling them, ‘Hey, being black is going to cause you some issues.’”

Those issues come up every day, he says. Air Force officers who outrank him telling racist jokes. Looks lingering on him for too long at a store or near a swing set during visits with white clients.

Can I help you with something? Do you know anybody here?

But this was different. “Nobody’s ever called the police on me.”

* * *

* * *

When a nation is at war, every soldier is a witness. As a mechanic, Ragland was never on the front lines, but he absorbed his own blows from America’s two decades of war in Iraq and Afghanistan. He watched coffins unloaded from planes. He walked the hallways of the military hospital in Germany while his newborn son and girlfriend rested. He saw injured soldiers in wheelchairs.

“I grew up in the military,” Ragland says. “It made me realize, as a citizen, you have a role. It made me acutely aware of citizenship. It’s not just a given. People do things for you to be able to live this way.”

“Shall we be citizens in war, and aliens in peace? Would that be just?”

Frederick Douglass, 1865

There’s a long history of black veterans invoking their service to claim citizenship rights denied to black Americans. The Douglass quote (above) opens the first chapter of “Fighting for Democracy: Black Veterans and the Struggle Against White Supremacy in the Postwar South,” a 2009 book by UW political science professor Christopher Parker.

After every major war, black soldiers have returned to civilian life asking a version of Douglass’ question, says Parker, who served in the Navy for 10 years. Black veterans came back from World War II and the Korean War, for example, ready to challenge white supremacy by joining the Civil Rights Movement.

For Ragland, after the wars of his own generation, Douglass’ question remains unanswered. “How much more do I have to pay to be a citizen? How much more do we have to pay? Tell me what else I have to do to be treated like an American.”

* * *

At Menchie's, with the officer still standing over him, Ragland took a breath. He noticed the mother getting upset.

He’s with us. What’s going on?

The police officer asked for his identification. He saw the confusion on the boy’s face. He’s supposed to shield children from this kind of adult drama.

Let’s go…

…he remembers saying to the mother. In the security video, the three walk out of the yogurt shop single file. The boy leaves first, carrying his cup of frozen yogurt. The mother follows. Ragland is behind them.

* * *

He used to go there to study between classes. He graduated in March. Asked what’s taken, Ragland responds in a series of short, sharp phrases. “My freedom. My humanity. My ability to look at society in a positive light. My ability to do my job. My trust and respect in the system.”

About a week after the Nov. 7 Menchie’s incident, Ragland talked to Seattle Times columnist Danny Westneat. “When you’re singled out for a certain type of thing and you represent a certain type of people, now this is your responsibility,” he says. “You have to react.” Westneat’s column came out on Nov. 16, and a flurry of media attention followed.

Kirkland Police Chief Cherie Harris and City Manager Kurt Triplett released a joint statement apologizing for an “interaction that did not meet the expectations of our community or the high standards we set for ourselves. As a result, Mr. Ragland and the other individuals with him were left feeling unwelcome in Kirkland. No one regrets this more than the men and women of the Kirkland Police Department. We are truly sorry.”

Ragland spoke at a news conference arranged by the Seattle-King County NAACP four days after Westneat’s column was published. He stepped in front of the cameras with two pages of typed notes. He knew the incident at Menchie’s would be shared and dissected on social media. He felt compelled to claim his part of the conversation. “I need my son to be able to look back and point to something—‘This is what my dad stood for.’”

* * *

Unease with black people moving freely in public is nothing new in the United States. When the Civil War ended, the defeated Confederate states enacted laws to control and contain how, when and where formerly enslaved black people could define their new freedom, says Megan Ming Francis, a UW political science professor who studies American politics and race. Vagrancy laws, punishable by arrest and prison time, established curfews and required ex-slaves to show employment papers and pay special taxes. A brief period of political power for black citizens during Reconstruction was followed by the backlash of Jim Crow.

Americans tend to think about racism as a failure of individuals, a character flaw, rather than a building block of the inequality and discrimination black people face everywhere from prisons to politics, Francis says. “That’s much harder and we don’t want to do that work.”

Ragland sees himself and what happened at Menchie’s as part of the longer historical continuum Francis describes. He carried his blackness into a yogurt shop, aware in the abstract that he is always a potential target but unprepared for the response his presence would provoke on that particular day.

The Menchie’s incident did not alter Ragland’s politics. He has long believed that addressing historical and contemporary injustice requires a broader economic solution. The news conference offered him the chance to make his case.

“We are an exceptional people with a very specific claim to justice and restitution,” Ragland said. “For the last four centuries, we’ve been enslaved, lynched, redlined, mass incarcerated and benignly neglected.”

In his remarks, Ragland invoked the idea of reparations, a concept percolating anew in the national conversation about race since Ta-Nehisi Coates published his article, “The Case for Reparations,” in The Atlantic in 2014. Once dismissed as a far-left pipe dream, the broad notion of apologizing and providing restitution for slavery is now a mainstream talking point in the Democratic presidential primary.

“Does that mean that everybody gets a check?” Francis says. “What reparations mean for a community is much broader. It’s a larger statement that we did wrong and we are trying, even though we can never repair the harm of slavery. We can never repair the harm of Jim Crow, of hundreds of years of federal policies that have benefited poor whites but not poor black people. We cannot rectify all of that harm and all of that disadvantage, but we recognize that, and we want to try to do something to make it better.”

“As a 10-year-old, you know what color you are.”

Byron Ragland, 2019

Two months after the Kirkland Police Department’s public apology, while Ragland was applying for graduate school, the department released a report concluding that its officers had not violated policy or acted out of racial bias. Still, the department changed its policy for responding to “unwanted person” calls, and the city hired a consultant to hold implicit bias trainings. “We believe that by improving our systems,” Chief Harris said in a statement, “we can significantly reduce the possibility that misunderstandings, such as the one that occurred at Menchie’s, occur again.”

For Ragland, what happened on that November evening amounts to more than a misunderstanding. It’s a reality he can never shed. At the Tacoma coffee shop, Ragland rubs his forearms as he describes what it is like to be black in public—a constraint he lived with long before the police asked him to leave the yogurt shop.

“It’s just like walking around all day with an extra-small sweater on,” he says. “It’s tight. It’s confining. You’re always uncomfortable. And you just got to function like this. While you’re over here with your extra, extra-small sweater on, everybody’s over there chillin’ with a tank top on—able to move and do all these things.”

After the Menchie’s incident, everything felt even tighter.

“Now, it’s my sweater, it’s my pants, it’s my shoes, my hat. I got gloves on. It’s a scarf,” he says. “It’s not even like you take it off at night. You have to plan your day by this kind of stuff. It’s a real thing about the way people go through life.”

Real, but not always acknowledged.

“If you don’t see it,” he says, “it’s easy for you to tell yourself it’s not there.”