The innocent eye The innocent eye The innocent eye

Collage artist Richard Kehl wants his students to take a fresh look at the world.

By Jean Reichenbach | March 1992 issue

Pity the mail carrier whose route includes Professor Richard Kehl's address.

Kehl, who joined the UW art faculty in 1968, sometimes assigns his students to dream up something “provocative” and send it to him, unwrapped, through the U.S. mail. Over the years hapless federal employees have carried to his door a semi-inflated inner tube, an automobile carburetor and an entire jigsaw puzzle—mailed at the rate of one piece per day.

“One time I had my students send something to me and nothing came, nothing came,” recalls the painter and collage artist. “About a week and a half went by and all of a sudden this man appeared at my door … and he had everything (mailed for this particular assignment).” Sandpaper, creatively affixed to one of the projects, had ruined a stamp-canceling machine. “He proceeded to tell me why it wasn’t acceptable,” Kehl adds.

Destruction of postal equipment may, indeed, be unacceptable. But almost anything else about the creation of art is just fine with this veteran teacher who strives “to do as little harm as possible” to his students.

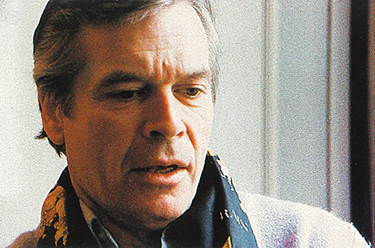

Richard Kehl

For the 55-year-old Missouri native, art permeates all of life and is inextricably bound to the human personality, “the way you live and breathe, the way you see the world. . .. I try to teach my students that drawing is not an isolated activity that doesn’t correspond to the rest of your life. It’s all of one fabric.”

Kehl urges his students, and everyone, to view the fabric of life with what he calls an “innocent eye,” free of the labels and value judgments imposed from the outside. “I was trained to paint like Cezanne a lot but now that I’ve got an innocent eye I don’t think Cezanne is so hot,” he says.

“The innocent eye … is about not naming things anymore,” Kehl says. “When you name something … you just put it in some category in your brain and you never see it again. A first-rate artist, equipped with an innocent eye, sees a different room each time he or she walks into it.”

Born in the farming town of Mexico, Mo., Kehl knew very early that he wanted art to be his life’s work. He has bachelor’s and master’s degrees in fine art from the Kansas City Art Institute. While still a student, Kehl gained recognition for his abstract expressionist paintings.

Today he works primarily with collage. His commissions over the years have come from such varied clients as Pepsi Cola, the Vatican (a 40-foot mural for the Vatican Pavilion at the 1964 New York World’s Fair), the Seattle Symphony, Mother Jones magazine, and a California restaurant chain seeking menu illustrations. His photo collages and paintings have been shown in more than 70 galleries including some in New York, Paris and London.

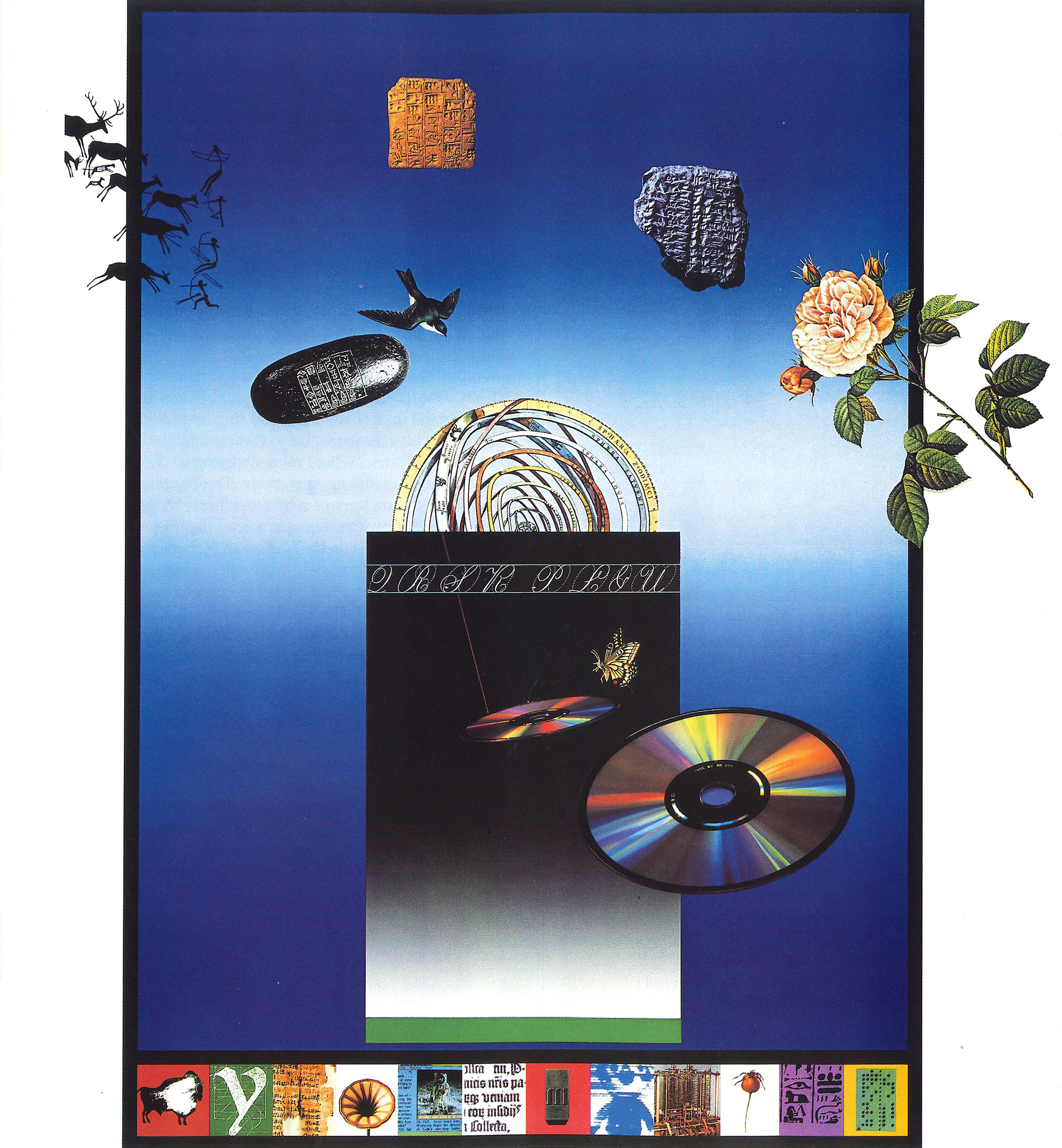

Kehl’s photo collages typically combine widely disparate objects which usually float, often in a somewhat jarring arrangement, on a background of color. A given piece might include a human figure, a globe of the constellations, a pair of butterflies and an old building.

His studio, with its sweeping view of Seattle’s Lake Union, contains huge folders filled with images painstakingly cut from old publications. These provide the mother lode of material from which Kehl selects his collage elements. Sometimes the elements come together into a finished work quickly, sometimes not.

“What I'm really trying to do in my collages is to make the mystery exact. The mystery of the universe, the mystery of why we're here, how we relate to things, how the stars are part of us.”

Richard Kehl

“It’s an act of listening to what they (the elements) want rather than my insisting they do a certain thing,” Kehl explains.

Kehl doesn’t expect anyone, including himself, to “understand” his creations. “I don’t want to tell little stories,” he explains. “What I’m really trying to do in my collages is to make the mystery exact. The mystery of the universe, the mystery of why we’re here, how we relate to things, how the stars are part of us.”

Mysteries don’t lend themselves to analysis or logical explanation. Nor do they yield their magic in traditional teaching situations, says Kehl, who has taught at a variety of institutions including the prestigious Rhode Island School of Design. After earlier stints as instructor and visiting assistant professor, he joined the UW as an assistant professor in 1968. “That was back in the old hippie days,” he recalls. “I was the one who was going to teach the alternative courses where we put all the disciplines together. We had courses that had no name … so no one would know what to expect.”

From the first, he had a big following. “We Love Richie” graffiti appeared on campus walls every now and then, recalls Gary Draper, ’68. “I think it embarrassed him because, to this day, he doesn’t like to be idolized.”

Nearly 25 years later, the unexpected still characterizes the teaching of this man. He introduces himself to his students as their “partner in crime” and tells them from the outset that in art, at least, the only opinion about their work that really counts is their own. “They’ll just have to do what I do: hang around people who like their stuff,” Kehl says.

Decades after he sat in Kehl’s classroom, Draper remembers an early assignment. “We had to bring in something that would follow us,” recalls Draper, who chose a kite to which he had attached items that don’t ordinarily fly such as an inflatable train.

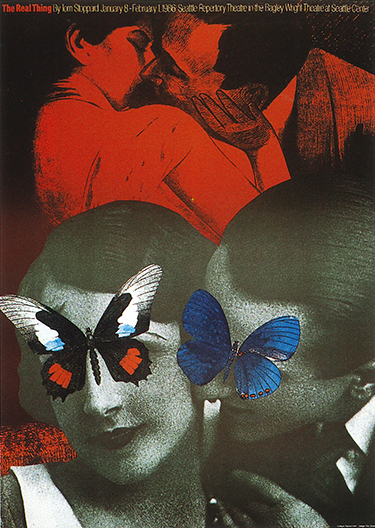

Kehl’s poster for the Seattle Repertory Theatre’s 1986 production of “The Real Thing.”

Kehl is somewhat skeptical of the traditional method of teaching art in small, sequential segments: drawing cones and circles before attempting to draw from a live model, or drawing black and white before trying color. He often breaks the mold. “We start drawing the figure right away. We draw color right away . … I teach (design) as a way of stretching your imagination,” he says.

He’s also deeply concerned about educational institutions in general and the harm they inflict on students. “By the time they’ve gone through the school system, the ‘system’ has just about got them where they want them,” he laments. “They’ve lost the ability to ask questions. . .. They’ve become good students [and] they’re really boring. One of the first things I have to do is get them so they feel spirited again, in love with life again.”

Part of that process is helping students identify what they really want to do with their lives. Kehl’s proud of the frequency with which comments such as “he changed my view of the world” appear on student-evaluation forms.

Draper, who writes and illustrates children’s books under the name Cooper Edens, credits Kehl with nurturing the kind of thinking that today gives his books a non-linear, “Zen-like” quality. From Kehl he learned to think “horizontally,” and to look at the periphery of things instead of head-on. Kehl introduced him to the beauty to be found in random arrangement and in ordinary, non-art objects.

Kehl strives to break, or at least loosen, the long-ingrained grip of logic and linear thinking and, through art, introduce his students to the magic and the mystery of a universe where “there aren’t any answers and there probably aren’t any questions either.”

How can art accomplish this? For one thing, it teaches people to pay close attention. “That’s what you do whenever you learn to love something,” he points out. “When you fall in love with your husband, or child, or an idea, or a cake that you’re baking.”

Kehl started as an abstract expressionist painter because abstract expressionism was in vogue in his art school days. He describes his decision to give up painting as the first of several “back-to-zero” moments in his life—opportunities to check the authenticity of his personal values and priorities. “You’ve read about people who’ve become wise in the world because they’ve been put in prison … or they’ve had an illness. It interrupted their usual process of seeing the world.”

Fortunately, back-to-zero experiences can also be voluntary. Suspend your belief system. View everything in the universe—however previously cherished or abhorred—as essentially equal, Kehl suggests. The values which still ring true are very likely authentic and worth keeping.

Kehl himself has emerged from back-to-zero more deeply fascinated by mystery, more interested in paying attention without feeling compelled to understand, and, in his words, “rededicated to the things that make me more whole, as opposed to specific and narrow goals that I sometimes pick up without realizing it.”

These experiences have come every eight or 10 years to Kehl, whose career has also included fashion drawing, filmmaking, and designing for Hallmark cards. He has published several books including how-to-be-creative works with whimsical titles such as 100 Ways to Have Fun with an Alligator and How to Make a Zero Backwards. Described by the prestigious art publication Print as having “a mind like a library attic,” Kehl reads voraciously and collects quotations—which he prefers to call “Zen zingers”—as enthusiastically as he collects and clips images for his collages. He has published two books compiling some of his favorites, Silver Departures and Further Departures. A 1986 collection of photographs (his own and others) called The Feminine, celebrates the feminine quality in everyone.

Several years ago Kehl promised his agent that every Sunday he would mail her something in a hand-decorated envelope. One week it happened to be a cutout of Britain’s Princess Margaret glued to a magnet and intended for her refrigerator door. “When I dropped it in the mailbox I heard it go ‘clunk,’ (as the magnet adhered to the inside of the box),” he laughingly recalls. He walked away thinking “I don’t know when they’ll deliver that.”

Mail carriers across the nation will soon be toting Richard Kehl creations thanks to a collection of decorated envelopes on sale this spring. Lacking magnets or sandpaper, they should be pure pleasure to send, receive and even deliver.

At top: Kehl’s poster announcing Microsoft’s 1987 CD ROM Conference in Seattle.