When Noreen Skagen joined the Seattle Police Department in 1959, she almost didn’t meet the minimum height requirement of being at least 5-foot-4. So she piled up chairs to reach some ceiling pipes, hung there as long as she could and, voila! She stretched herself to a height of a little over 5-4. Thus began a stellar career in law enforcement that paved the way for generations of women.

Skagen, ’52, who died Aug. 25 in Mill Creek at age 87, spent 30 years with the police department, rising through the ranks to become the city of Seattle’s first female assistant chief of police. That led to an even bigger achievement in 1989, when then-Sen. Dan Evans, ’48, ’49 tapped her to become the first female U.S. Marshal of Western Washington, a post she held for five years. Skagen succeeded in a field dominated by type-A men by being extremely competent, bringing out the best in everyone she met and employing a humility not often found these days in leadership.

Skagen, who grew up in an Italian family in Seattle, majored in journalism at the UW, and then after a divorce needed to go to work to support herself and two young sons. She became a police officer at a time when women weren’t assigned to go on patrol. Throughout her distinguished career, she combined compassion with a tough-minded willingness to do right, especially for abused children, even when it meant putting herself in potential peril. It wasn’t uncommon for Skagen to chase down runaway teenagers in scary parts of town where police weren’t welcome. In the early years, when women first broke the gender barrier in police departments, women officers acted as part cop and part social worker. Helping at-risk youth was a lifelong passion for Skagen, who later served on the boards of Childhaven, Kid’s Place and the Boy Scouts of America.

“We really took on the burden of the welfare of all the children at risk in the city,” Skagen told author Adam Eisenberg, ’92, for his book “Different Shade of Blue,” an account of Seattle’s first female policewomen.

Skagen’s husband, Roy, ’59, to whom she was married for 48 years, says that she was able to cope with what she saw as a police officer because she was compassionate yet also had a balanced life as a wife and mother of two sons. Her family life gave Skagen great joy that sustained her in her demanding work.

Policing in the 1960s thrust Skagen dead center into the events of that time. She was injured trying to restrain eager concert-goers at the Beatles’ first Seattle concert in 1966. Ironically, she was assigned to the first-aid room at the concert but the kids went wild and she ended up joining other officers in riot control duties and ended up black and blue with bruises the next day.

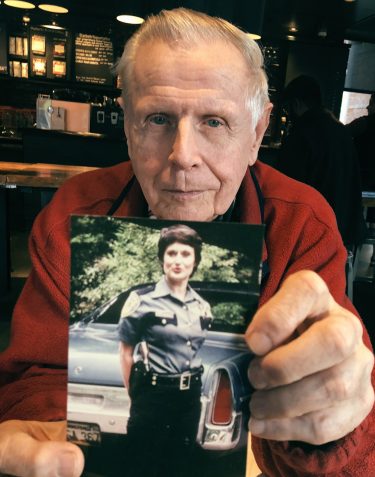

Roy Skagen, ’59, holds a picture of his late wife Noreen during an interview with Columns Magazine. (Photo by Julie Garner)

Skagen participated as a judge in another American tradition of the 1960s: The Miss America pageant. She served as a judge many times for the Miss Washington pageant and once, at a time when she was U.S. Marshal, for the Miss America pageant in Atlantic City.

“It was an enriching experience to be around young women with such accomplishment and drive. Many of them became like daughters to Noreen and myself,” says Roy.

Noreen Skagen didn’t mix her personal and professional lives, that is until Roy came along. Roy, who served as an officer in the U.S. Marine Corps, holds the record for shortest time rising through the ranks of the Seattle Police. He was only 34 when he became assistant chief of police. He served also as chief of detectives.

Getting a date with Noreen was no easy task. So, Roy invited her out for coffee at the Lamplighter, a legendary coffee shop across from police headquarters downtown. She agreed but only because he used the ruse of asking her advice. Ultimately, Skagen triumphed in his courtship and the pair married. The Skagens truly are a family in blue. They raised two sons—retired Seattle Police deputy chief Clark Kimerer and retired Burien police chief Scott Kimerer.

Roy explained that the U.S. Marshals make more felony warrant arrests than any other law-enforcement agency. “They look for the bad guys after the DEA or the FBI issue a warrant,” he says. “Let’s just say, being on the federal Marshal’s list of bad guys is a villain’s worst nightmare. The Marshals across the country are a crack team. You don’t want to be on the federal Marshal’s list.”

Bob Christman, who is now retired and living in Snohomish, was the No. 2 Marshal at the time Noreen was the No. 1 for the Western Washington district. He was tough and as crusty as John Wayne, Roy recalls. Christman initially wasn’t sure about having a woman in charge but today, he says that Noreen was the best and brightest leader under whom he served.

Roy says she’d make flights dressed in a Marshal’s jumpsuit, with a badge, and a revolver to supervise the transfer of desperados to the U.S. Penitentiary in Leavenworth. “She’d have to walk down the aisle of the plane with all those convicts looking at her like ‘what is this’? Very creepy, but part of her job,” says Roy.

After she retired in 1994 and spent her time enjoying books, opera, her garden and the many friendships she had, the city of Mill Creek called her out of retirement at age 70 to serve as interim police chief. The officers wanted her for the permanent post and one even begged, “We’ll put up a statue of you in front of city hall if you’ll be our permanent chief.” With her usual tact, Noreen declined, enjoying a good laugh at the idea of a statue, Roy recalls.

On the second Wednesday of September for the past 74 years, Seattle’s finest gather en masse for an annual banquet at the department’s training center to honor all of the officers who have died in the previous year. This year, sadly, Noreen’s photo was among those of the honored dead. With an honor guard in full uniform and a police officer playing “Amazing Grace” on bagpipes, the department paid homage to those they had lost.

After the ceremony Roy was inundated with grieving people who wanted to share their story about what Noreen had meant in their lives. The years with his cherished wife and the condolences and memories that people shared are helping the Skagen family cope. “I never met anybody like her,” Roy says.