It's 7:30 a.m. at Meany Middle School and the day has already begun. Math teacher Jane Doe stands at the door of her classroom listening to the noise that rivals Husky Stadium on game day. Lockers slam, books hit the floor and a crush of 11-to-14-year-olds shriek with laughter. In 15 minutes the tardy bell will ring and the first class will start.

From that moment on, Doe knows, she will be besieged by students — about 150 in the course of the day. She teaches five academic periods, conducts a homeroom-style “events” period and has a scant 50 minutes to herself during a “prep” period. Lunch is a 30-minute rush in the teachers’ lounge.

When school ends at 2:15, Doe will turn to correcting homework papers and preparing for the next day’s classes. She often stays at the school until well after 5. “The adrenaline is pumping every minute,” is how she describes her day.

It’s 8 a.m. at the UW’s College of Education and Assistant Professor John Jones is feeling harried. He has two classes to prepare for and is running a research project on the side. In addition, he serves on several committees and is scheduled to present a paper at an upcoming professional conference.

He thinks back to the days he taught in public school and felt frustrated with the status quo. “I want to do research,” he had thought. “Schools are operating on a 19th century model that just doesn’t serve the needs of today’s students.”

Now, a graduate degree later, Jones finds himself doing lots of research, but he’s not thinking much about its effect on classrooms. He’s thinking about publishing, in the right journals, because without that he won’t get tenure.

John Goodlad

What’s wrong with these pictures? Plenty, says UW Education Professor John Goodlad. A nationally known researcher who has tackled the public school and teacher preparation programs in his books, A Place Called School and Teachers for Our Nation’s Schools, he maintains you can’t improve the public schools without changing the way teachers are taught.

Like harried pastors of poor churches, schoolteachers are racing from one activity to the next, pressed to minister to many needy students. There is no time for renewal of their own quest for learning. They are hamstrung by an antiquated school structure, isolating them from one another and forcing them into behavior that is incompatible with student learning.

Education professors are more like monks. They spend most of their time in their quiet cloisters thinking about teaching and learning. But their meticulously designed research projects are reported in journals that teachers don’t read. Their own forays among the classroom flock are limited to the time it takes to run those projects. Caught on an endless road to the beatification of tenure, they give scant attention to their institution’s teacher preparation program. And they rarely think of getting advice from real-world teachers.

Each group, says Goodlad, needs the other. Teachers need to collaborate with each other and with principals; college professors need to collaborate with each other and with schoolteachers and principals. Ultimately, there must be an equal partnership between the two institutions — public schools and colleges of education.

Can this odd couple make it together? Goodlad thinks the marriage is necessary, if not ideal. The juxtaposition of the schools’ “action-oriented” culture and the “inquiry-oriented” culture of the university, he says, holds promise for “shaking loose the calcified programs of both.”

The UW is listening to Goodlad. In the last eight years, the University has started numerous partnerships with public schools, and not all of these efforts are in the College of Education. Collaboration has not yet succeeded in revolutionizing either the schools or the University, but it has made inroads.

A prime example of this initiative is the “Puget Sound Professional Development Center.” At Seattle’s Meany Middle School, teachers, principals and professors are working together to prevent teacher burnout and prepare would-be teachers for a new world.

* * *

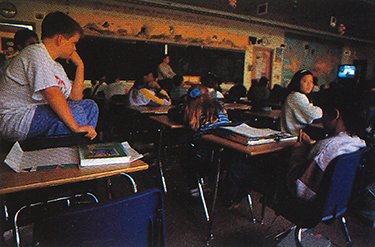

Meany Middle School — named for the UW's "Grand Old Man" Edmond Meany — was built in 1963 and has the rambling, one-floor layout of that era. Located at 21st and Republican, just a stone's throw from one of Seattle's major drug trafficking areas, it attracts a diverse student body representing every strand of the larger community.

Brad Wilson has been at Meany just three years, although he is a classroom veteran and former principal. Wilson teaches 8th grade math at the school, and spent last year as supervising teacher to a UW student placed in the school as part of the initiative’s teacher preparation program. It was a good experience, he says.

“A lot of teaching interns are only interested in their own classes, but this guy took an interest in the whole school. He went on field trips, sat in on meetings and assemblies, everything.”

The attitude is one the initiative tries to instill in all its interns, who are assigned to a school for the whole year, rather than the one quarter as required in many other internships. They begin the year observing several classrooms, not just one, and they also have a chance to meet with other school staff, from lunchroom workers to counselors.

Wilson liked the set-up, which allowed his intern to break in gradually. “By the time he took over the classes, the students were ready to accept him.”

The experience was an eye-opener for Wilson, who initially refused when asked if he would take an intern. “I’m pretty territorial,” he admits. “I really don’t want anyone else in my classroom.” Now, however, he says he’d do it again.

* * *

The Professional Development Center was created four years ago with funding from the Ford Foundation. It is a partnership between the UW and four Puget Sound middle schools — College Place in Edmonds, Kellogg in Shoreline, Odle in Bellevue and Meany. Two of its components are a teacher preparation program for middle schools and a renewal program for practicing teachers.

In an almost revolutionary step, middle school teachers and principals were included on its planning committee from the beginning. Their practical knowledge and the faculty’s access to the latest research created the type of collaboration Goodlad advocates.

Aspiring teachers in the program take a two-quarter, 12-credit professional seminar together, team taught by middle school teachers and UW faculty. Learning to work in teams is part of the instruction. Once in the schools, interns have a “site supervisor,” a teacher from that school who meets with them and helps them reflect on what they’re experiencing.

“Schools of the future demand a new type of person,” says Center Director Nathalie Gehrke. “In the past, people were attracted to teaching because, once in the classroom, you are autonomous. Now we need people who are team players. If we want that result, we have to model it in our program.”

* * *

Fall brings an unexpected influx of students to Meany — 100 more than projections indicated. The school is in an uproar, with book shortages and room overflows and the prospect of massive student schedule changes.

At the eye of the storm is Principal Carol Flagg, who came to Meany three years ago, when the UW initiative was already a year old. Now she’s trying her best to salvage her “teams” — teachers of different subjects all assigned to the same group of students.

Due to the overload, she can’t make it work in every case. She’s forced to assign one group of sixth graders to teachers who also teach other grades. Flagg is up against what Goodlad calls “school regularities.” District rules assign teachers on the basis of total school population, not the number in any given grade. “We want our teachers to work in teams,” Flagg says. “I should be able to plan them way in advance, but I can’t.”

The team idea isn’t dead, however. This same chaotic fall, one team is excitedly beginning its first attempt at an integrated curriculum. Spanish teacher Laura Dybvad and her seventh grade colleagues are launching a year of looking at a common theme — change. Each teacher will be organizing lessons around the theme, with the aim of teaching goal setting and problem-solving skills.

Dybvad learned about integrative curriculum through the center’s renewal program for practicing teachers, and is enthusiastic in her praise for it. “The program offers teachers in the building a chance to grow professionally and take a look at new ideas,” she says.

The renewal program includes “fireside chats,” informal talks by UW professors on topics chosen by the teachers, and meetings with teachers from the other middle schools. There’s also a new computer system which allows teachers to communicate with their non-Meany colleagues via electronic mail. The computers allow them to scan a database containing — among other things — new teaching ideas.

* * *

Fran Hunkins has been a college professor for 25 years, but he recently spent one day a week at College Place Middle School in Edmonds. While there, Hunkins served as a resource for the teachers and helped one of them carry out a simple research project in the classroom. Hunkins' position was "professor in residence," another aspect of the Professional Development Center concept. Meany has not yet had a professor-in-residence, and for many staff there this is a missing link.

“The center has tried to make us believe that professors want to come here and teach and do research on middle schools,” said School Librarian Phil Quinn. “I haven’t seen them coming.”

The UW comes up against its own form of “school regularity” in finding professors-in-residence, Gehrke says. The ones who are best for the job are busy, and working out their schedules is tricky. More important, she’d rather not send anyone until the individual school’s goals are known, allowing the UW to pinpoint the best person for the job.

Goal-setting requires a site-based, decision-making council, a group composed of teachers, students, administrators, parents and representatives of the business community. Such a group does not yet exist at Meany, though Principal Flagg vows it will before this academic year is over. Teachers, she says, often resist the idea.

“On the one hand, they want to be part of decisions, and yet at the same time they’re saying ‘Just tell me what you want me to do.’ ”

But that attitude may be changing. Says Librarian Quinn, “The main thing, I think, the development center has done is to help us think of ourselves as professionals again.”

* * *

Class is underway but one table of boys is talking loudly. When one boy is asked to move to another table, he slams his books down hard, mumbling as he goes. After another boy is sent to the hall, his companion takes his calculator out of his notebook and begins playing with it. Meanwhile, a girl who has been moved for talking kicks a chair, saying aloud "This chair is in my way." Disruptions are continuous, effectively bringing the day's lesson to a halt.

Though it’s normal for any school to have its share of unruly kids, Meany’s location brings it more than the usual number of “at-risk” students. Last spring more than 100 (out of 635) were listed as in danger of failing two or more subjects.

“Drugs, poverty, neglect, you name it. These kids have a lot of problems interfering with learning,” says Ben Wright, who deals with serious discipline problems and puts together intervention teams for troubled students. Made up of counselors, administrators, teachers and parents, the teams try to identify what the student needs and put him or her in touch with community resources.

This year that process will be aided by a new program at Meany which will place representatives of social service agencies in the school to make them more accessible to students and to get them talking to each other. This effort involves five UW schools: public health and community medicine, education, public affairs, nursing and social work. It is coordinated on campus by Ted Teather, Karen Hulbert and Michelle Bell. UW students from all five disciplines will be working together in seminars at the UW, after which they will serve internships in the agencies involved.

“This is a revolutionary idea,” says Wright. “Now the social worker will know what the teacher is doing and vice versa. Through collaboration, we’ll be able to get away from the ‘band aid’ approach and deal with the total child.”

* * *

In four years of hard work, the Professional Development Center has chipped away at the iceberg of educational dogma, but no one involved believes it's melting away. Goodlad thinks school-university partnerships should be long term, maybe permanent. Colleges of education, he reasons, need top notch schools in which to place their aspiring teachers, and schools need a constant infusion of new ideas if they are to remain top notch.

Allen Glenn

But the middle school project has inspired imitation. This fall, Professional Development Centers were started in six local elementary schools. And UW Education Dean Allen Glenn is spearheading the overhaul of the University’s other teacher preparation programs along the lines of the middle school program (and yes, public school teachers are participating in the planning).

Nonetheless, Glenn and Goodlad are both aware that deeper, institutional changes are needed for schools to truly flourish.

“Until we challenge the givens,” says Glenn, “nothing is going to change. We have to look at all the automatics — the hours we’re open, the way we structure classes, everything.”

And, Goodlad adds, “You can’t expect teachers to simultaneously teach under one system and create another.” If we don’t give teachers extra time to plan the new, he says, “we will not have the new.”

The middle school project is part of the Puget Sound Educational Consortium, the granddaddy of all College of Education partnerships with schools. Founded in 1984, the consortium — which includes 11 school districts — is an umbrella organization that fosters contacts between the University and the schools.

The middle school project is part of the Puget Sound Educational Consortium, the granddaddy of all College of Education partnerships with schools. Founded in 1984, the consortium — which includes 11 school districts — is an umbrella organization that fosters contacts between the University and the schools.

A sampling of other active partnerships include: